[This research was funded in whole or in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), Grant numbers 183016 and 192205. Olivier Keller, Jenny Furter, Leandra Sommaruga and Simon Eugster have assisted this project. We would like to thank all research participants for sharing their time and experiences with us.]

At the Huawei office in Zurich, a large plastic black-and-white cow stands in the reception area, greeting visitors at the entrance. A sign above the cow reads ›Guest Cow. Welcome to Huawei Switzerland‹. By appropriating this emblem of Swissness, which acts as an icebreaker and a selfie backdrop for visitors, the Chinese technology company presents itself as a little more Swiss and therefore trustworthy, countering negative headlines amidst geopolitical debates. Four decades ago, it would have been unthinkable for a Chinese company to develop and market high technology abroad, especially in Switzerland, one of the richest and most ›innovative‹ countries in the world.1

At the end of the 1970s, Swiss and other foreign companies were debating whether to expand into the People’s Republic of China (PRC or ›China‹). ›Do we want to be left out in the cold or even have them as competitors, or do we want to become partners?‹2 A member of the Dyes & Chemicals Division of the Hong Kong branch of Ciba-Geigy posed this question to the management in Basel in 1979, having analysed opportunities and threats from the Chinese market in a report shortly after the Chinese government had announced it would open up its economy to foreigners. As we know today, both scenarios came true, as Ciba-Geigy, along with other companies, actually partnered with Chinese companies. The Chinese economy has simultaneously wrought intense competition in various industries, especially the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) sector.

Our article focuses on these Swiss-Chinese economic entanglements since the late 1970s. We consider two complementary historical and anthropological case studies on Swiss economic activities in China (late 1970s–2000s) and Chinese economic activities in Switzerland (2000s–2020s). These periods are remarkable: China changed from a rather isolated, socialist economy into an export-oriented, socialist market economy, thanks to technologies imported through Joint Ventures (JVs), and to Chinese companies going global. This article sheds an empirical light on the role of Chinese and Swiss companies and their representatives that form the basis of these major shifts. Furthermore, we explore how this dynamic and increasingly geopolitically contested transnational field may be better understood by combining the methods of contemporary history and sociocultural anthropology. We also address methodological challenges and opportunities in relation to researching global settings that are relevant beyond China and Switzerland.

Diplomatic and economic relations between Switzerland and China developed relatively late, in the mid-20th century, and since then both sides have often described the relationship as special. During the colonial expansion of various European states into imperial China in the mid-19th century, the Swiss federal government discussed a possible trade agreement with China. This project was abandoned, however, due to a lack of interest in Swiss business circles.3 This changed in the early 20th century, when Swiss enterprises established sales markets in China along with other foreign firms. In 1949, when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC), most of these companies settled in Hong Kong in response to Mao Zedong’s takeover of the mainland. Still, Switzerland was one of the first countries to recognise the PRC, in January 1950. During the Cold War, Switzerland, with its international organisations, served as a hub for Chinese propaganda and soft power in Europe. Switzerland continued trading with the PRC while other Western European and North American countries embargoed the country, only giving in when pressure from the United States became too strong.4

Yet from the mid-1970s onwards, economic ties between the two countries became closer again. In the early 1980s, a Swiss company established the first-ever Western industrial Joint Venture in the PRC. In the 2010s, economic and financial ties between the two countries tightened further. In 2014, a free trade agreement (FTA) between Switzerland and China came into force – the only Chinese FTA in continental Europe.5 In 2015, direct trading between the Chinese Renminbi and Swiss Franc was launched,6 making Switzerland one of the few trading centres for the Chinese currency in Europe. One year later, Switzerland became a non-regional member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB),7 a Chinese initiative. In 2019, Switzerland was one of the first Western European countries to sign a Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Memorandum of Understanding.8

Although generally good, the relationship between the two countries has not always been smooth, as exemplified by the Swiss government’s 2021 China Strategy,9 which outlines a range of challenges related to Sino-Swiss collaborations. Yet in December 2022, the Swiss Federal Council again decided not to join an EU embargo on China for human rights violations,10 and the China Strategy de facto expired at the end of 2024. All of these particularities demand a closer investigation of the past and present economic entanglements between the two countries, as well as a reflection on how to study this period and field, which is difficult to access.

1. Approaching Swiss-Chinese Economic Entanglements

The subject of Sino-Swiss relations is underrepresented in the broader historical and social science literature. Existing research mostly focuses on the Cold War era11 or on contemporary international relations, politics and business case studies.12 China’s reform and the role of JVs in the 1980s and 1990s were closely studied by scholars from disciplines such as economics and law at that time. However, this literature investigates JVs either primarily through their impact on technology, capital, and know-how transfer, or as a business model, but never focuses on the actors.13 The authors describe the requirements for an optimally running JV instead of considering everyday working problems. For a historical approach, these studies must be considered as mostly normative sources. They provide insights into the historical archetype of a JV, but their genesis must also be understood in this context. Today, historians are devoting more time to this era, focusing on Chinese political institutions and their reform.14

While this research provides an important basis for us, we take a comprehensive yet actor-centred focus on the companies, tracing Swiss actors’ attempts to enter the Chinese market and vice versa. This allows us to go beyond mere policy analyses by looking at companies’ and people’s actual practices, to render visible the actors, shift attention from cost-benefit analyses to a more historically, socially and politically embedded view, and consider economic transitions over a longer time span. This draws attention to how the flows of capital, technologies, people, knowledge and ideas move from Switzerland to China and back. Here we also take inspiration from the idea of ›Global China as method‹, which approaches China as an integral part of the global capitalist system, instead of a separate ›Other‹.15

The past and present of Swiss companies in China and Chinese companies in Switzerland remains mostly unknown beyond the macro level, partly because of the difficulty of gaining access to this field. We therefore follow a transdisciplinary approach and draw on a multiplicity of complementary sources. The first case study (Swiss companies in China, 1970s–2000s) rests on an extensive source analysis from company and federal archives from 1978 to the mid-1990s. Company archives contain correspondence, trip reports, and feasibility studies from their expansion into China. The Swiss Federal Archive has documented correspondence with the Swiss Embassy in Beijing and Swiss companies in China. Additionally, oral history interviews provide important and rarely recorded information about everyday problems in cooperation between Swiss and Chinese employees. These interviews also make connections visible, for example about decision-making processes that are difficult to reconstruct from written sources. The company archives’ business sources almost exclusively feature men, although interviews sometimes provide glimpses into the often invisible world of women who accompanied their Swiss husbands to China.

Interviews are also a way to bridge our two case studies, which both fall – at least for a certain period – under the 30-year protection period of most archives. On request of the archives and the interviewees we have mostly used pseudonyms (indicated with a ›(p)‹). This aligns with the ethical standards in anthropology, where anonymising interviewees and observations, which are often highly sensitive, is common practice in order to protect privacy and do no harm. Simultaneously, we strive to provide enough information to ensure that our findings are reliable, e.g. by disclosing the names of the companies, which would also be anonymised in anthropology. We try to account for the inherent conflict of objectives in historical research between the ideal of intersubjectivity, i.e. traceable sources, and the protection of interviewees and the research itself.

Further, Swiss, English-language and Chinese newspaper articles and online media are important sources for this article. They are part of the discourse about and construction of the respective realities of various international and Chinese audiences. In the 1980s and 1990s, Swiss media outlets presented China as a barely known and rapidly developing country. Accordingly, many articles have overstated the short-term effects of China’s policy changes while understating the long-term impact of China’s reforms. Or, as a former General Manager of a Swiss JV in China mentioned: ›I have only regretted one thing in these thirty years in China: That I never kept records, every time these doom scenarios about China were announced.‹16 Nevertheless, these articles provide well-documented accounts of significant events and offer insights into Swiss interpretations of Chinese reforms during that period. This is important as in company archives questions of human rights or the 1989 Tiananmen protests are often only mentioned in a ›change through trade‹ (Wandel durch Handel) credo, or not at all, possibly because not all documents found their way into the archives.

The Swiss and English-language media cited in the second case study (Chinese companies in Switzerland, 2000s–2020s), which target business actors and the wider Swiss and international public, are either technically descriptive or highlight the perceived Chinese economic and technological rise and related geopolitical dangers. The quoted Chinese media articles stress the economic-technological value of bilateral company collaboration and communicate government directives to the Chinese public.

Additionally, the second case study draws on ethnographic and documentary research conducted in Switzerland between 2019 and 2023.17 This comprised narrative and oral history interviews, informal conversations, and written correspondence with employees from Swiss and Chinese ICT companies. Contrary to conventional ethnographic research that studies people in subordinated social positions, this article involved mostly ›studying up‹,18 i.e. researching people with high social status and power. In the ICT sector in Switzerland these individuals are commonly male, while in China some women hold high-ranking technical positions. Studying up meant that our interlocutors were aware of their company’s interests and rights and that they might read what we publish about them. This created additional challenges. On top of more general ethical considerations, we had to be careful about the legal implications of disclosing company secrets and putting our interlocutors at risk in relation to their employers. Related interviews and conversations took place during participant observation in company offices, showrooms, network locations, and industry events. Over the course of our research, Chinese companies increasingly became a political issue, rendering long-term ethnographic studies within the companies impossible. Therefore, a strategy of ›multi-sited ethnography‹19 was adopted, complemented by an analysis of media content, company websites, brochures, trade registers and stock market information.

Taking account of the complexity of these circumstances, our article tackles the problem that the periods and topics covered can only partially be accessed by using historical or anthropological methods alone. Thus, we argue for creatively combining such methods in order to better understand Swiss-Chinese and other global economic entanglements. Moreover, we suggest that, to further understand transnational contexts of economic and other entanglements, it is fruitful not only to study the selected localities, but also to pay attention to the multi-directionality of exchanges over a certain period.

2. Increasing Economic Entanglements in the Late 1970s

In Swiss enterprises’ archives, almost all economic reports from the 1980s mention the huge new opportunities of the Chinese market. In almost thirty years under Mao’s socialism, the CCP tried hard to avoid outside influences as it built up a self-reliance economy. When Mao died in 1976, a new government under Deng Xiaoping started to reopen the Chinese economy to the outside world in 1978, thus arousing the interest of foreign investors.

Deng perceived China as lagging economically and technologically behind Western countries, leading him to announce his ambition to catch up by the end of the century.20 He intended to achieve this goal by reforming the economy and allowing competition on a selective basis, but also by appropriating foreign technologies to develop industry. In his 1980 report on future business opportunities in China, Erwin Schurtenberger, then Swiss Embassy Counsellor and later Ambassador, interpreted the Chinese reform policy. He noted that the motto of ›buying chickens instead of eggs‹, which was, according to him, often cited in China until 1979 in reference to a self-reliance economy, changed to ›buying books about poultry farming instead of chickens‹.21 To access new knowledge, the Chinese government sent delegations to Western countries to contact foreign firms, negotiate trade contracts and buy technological equipment.

Conversely, an increasing number of foreign businesspeople went to China to find a new market for their products. Enterprises were eager to prepare their employees for their first encounter with what seemed to them largely unfamiliar aspects of Chinese culture, often by means of oversimplifying company concept papers, such as a 1982 concept from the Pharma Division of Ciba-Geigy about the ›Mindset of the Chinese‹. According to this concept, ›[t]he Chinese think in terms of complementarity of opposites i.e., they consider clear statements or yes/no answers to be too one-sided and often »incorrect«‹.22 The concept continued that ›the Chinese expect from foreign negotiators [… to] have experience (= have grey hair)‹.23 A large market of knowledge about the Chinese economy emerged, evident in a variety of literature on business strategies in China. Most of our Swiss interviewees, both entrepreneurs and diplomats, ended up at some point in their careers working for consultancies specialising in the Chinese market. Such expertise was apparently in demand, and justifiably so; statements about a ›Mindset of the Chinese‹ were often too simplistic for a country with around one billion citizens at the time, whose socioeconomic landscape was rapidly changing.

Accordingly, the companies’ intercultural preparations were not always sufficient. For example, in the mid-1990s a Swiss manager travelled to China to open a JV for the Swiss cable producer Dätwyler. He recalled that, after a long boat trip from Shanghai up the Yangtze River, he finally arrived at his destination in rural Jiangsu Province. The manager thought it was the first time the locals had met foreigners: ›People looked at us as if we were extraterrestrials!‹ He recounted that the difficult JV negotiations were only successful due to the intercultural and legal advice of a professor from Peking University, and a China expert and lawyer from the Chamber of Commerce’s legal department. He remembered that he had to eat and drink lots of alcohol with the Chinese company employees and the local Party secretary to reduce mutual mistrust. His wife, who joined him two years later, recalled everyday challenges in China: ›Almost nobody spoke English, street signs were written only in Chinese, and when we went to a restaurant, we just had to point at something, because the menu was only in Chinese... We were totally unprepared.‹24

Despite an increasing economic entanglement, which – on the ground – played out in everyday intercultural encounters like these, in the late 1970s the Chinese government was anxious to remain sovereign. It did not want to get into debt, especially to foreign countries, as the Swiss embassy wrote to the Federal Office of Foreign Economic Affairs (FDEA)25 in September 1978.26 Until then, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Trade (MFT)27 had stated its four no’s: no to foreign investment in China, no to Chinese investment abroad, no to JVs,28 and no to government loans.29 However, these dogmatic principles soon made it difficult for the Chinese government to sustain industrial growth, due to the trade deficit.

Switzerland and China struggled to find a balance of trade. China had, and still has, a keen interest in Swiss goods, especially chemical products, machines, and watches. Yet China itself had little to export. From 1970 to 1985, Switzerland had a permanent trade surplus with China. A problem with this trade surplus was that the Renminbi (RMB) was not convertible, so foreign businesspeople would not sell their products for RMB, demanding hard currency such as the US Dollar (USD).30 At the beginning of the reform era, Chinese policy makers intended to balance the trade by exporting crude oil.31 But, as energy (along with transportation) became the bottleneck of the growing industry, they had to find other export items.32

A group led by the Swiss Trade Expansion Office went to China in October 1979 ›to demonstrate to our Chinese partners our firm intention [...] to help reduce the chronic deficit in the Sino-Swiss trade balance‹.33 But one problem was the perceived low quality of Chinese products, which did not meet Swiss norms, as Swiss business representatives stated in a joint economic commission with Chinese government officials.34 Another problem, as the Chinese often argued, was how the strong Swiss Franc affected the trade balance.35 This problem only grew as China’s imports of technology increased. China was maintaining negative trade balances not just with Switzerland, but also with other countries. Thus, sooner or later the country would run out of foreign currency.

3. The Chinese Market’s Opening for Joint Ventures since 1979

To prevent a slowdown of economic reform, the Chinese government made concessions in a different area. On 1 July 1979, they passed a groundbreaking fourteen-article short law concerning equity joint ventures (EJV). For a long time, Chinese officials had strictly opposed the possibility of JVs. In January 1977 the Swiss Embassy in Beijing had written a letter to the Federal Political Department (FPD)36 in Bern, stating that China rejected the question of JVs with ›brutal clarity‹ (brutaler Deutlichkeit).37 But eventually the narrative changed, and Chinese officials began to emphasise the benefits of JVs – that China would gain access to Western technology and management practices without having to spend foreign currency, as its share in these ventures could consist of infrastructure and workforce. They would also get access to their Western partners’ distribution systems.38 Moreover, Western enterprises would gain knowledge about the Chinese market, access to networks, and a partner who had mastered linguistic and cultural particulars.39

Despite these mutual interests, there were several conflicts between Chinese and foreign investors. While Western entrepreneurs were keen to gain access to China’s domestic market, the Chinese were mainly interested in exploring the export market, earning foreign currency and accessing new technologies.40 According to Margaret Pearson’s examination of the two sides’ bargaining power,41 foreign investors were only interested in building a JV if they would gain something from this new business relation, and would not risk sunken investments. At that time China did not have much to offer. The country had hardly any foreign currency or legal security, and patent and trademark protections were not guaranteed. Chinese products were of poor quality and not standardised, negotiation costs were high, and cooperation was difficult due to cultural and linguistic barriers.

Marco Müller (p), a former employee of BBC (Brown, Boveri & Cie.)42 now in his 60s, recounted in an interview the communication difficulties of working in China in the mid-1980s. At the time, according to Müller, a Swiss employee earned around a hundred times the salary of his Chinese counterpart. Therefore, JVs would employ as few expatriates as possible, often only a handful of technicians in an enterprise with thousands of employees. They barely spoke Chinese and were accompanied by translators. Also, Müller had to work as an individual expatriate together with his Chinese colleagues. Part of their job was building communication infrastructure. Communications would go through high-voltage power lines. The signal had to be transformed for transmission in the traction substation via frequency modulation. To test such a new line between a Point A and a Point B the workers had to communicate via a Point C. ›So one Person had to run from Point C to Point B. I was able to speak English, but not the others. So, we had to translate. But the translator was not a technical translator.‹ Müller explained how he had to give all the instructions in visual descriptions instead of technical terms. He remembered the high risk of misunderstandings and, convinced of his own approach, stated: ›Over time, I started to ask three questions in advance of every conversation, of which I already knew the answer, in order to steer them [i.e. the Chinese side] in the direction I wanted them to think.‹43 But Swiss businesspeople also had to learn how hard it was to advertise products when translators couldn’t explain technical terms. In a 1984 Swiss Radio and Television (SRF) review, a businessman tried to describe cellophane to his Chinese colleagues: ›This is real silk?‹, the translator, by far the youngest in the room, asked nervously. ›No, packing material. Paper. Transparent‹, the Swiss businessman clarified, gesturing as if he had thin material between his fingers, before the translator again attempted to find an adequate translation.44

The promise of the huge domestic market persuaded investors in the early 1980s to relocate to China, despite significant political and legal uncertainties. It also sparked a boom in foreign direct investment (FDI) in the 1990s – a time when the only risk seemed to be missing out on the opportunity.45 China’s relatively strong bargaining position, buttressed by the lure of its domestic market, made it possible for the Chinese government to enforce its position in the 1979 JV law. This was especially because the PRC was still under tight state control and JVs were – at least in the beginning – only possible with state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Contracts had to be approved by the government, which would enforce its own interest. Article 9 of the new JV law obligated JVs to purchase all raw and semi-processed materials from Chinese sources, if possible, which aimed to boost the Chinese economy. If not possible, JVs were required to use their own currency to prevent any outflow of foreign exchange. Also, JVs were expected to produce mainly for export, so they would create an inflow of foreign capital.46

The Chinese government’s requirements had various impacts on Swiss multinationals. The new Swiss Schindler plant in China began producing elevators for China’s growing cities in the early 1980s. This was not only the first ever industrial JV between the PRC and a Western company, but also one of the few which was not forced to export its products. The former head of the China-Schindler Elevator Co. Ltd. in China, Uli Sigg, now in his 70s and a key figure in economic and diplomatic bilateral relations at that time, explained: ›The [politicians in China] considered the lift industry a priority. [...] the goal was still autonomy between the individual provinces and big cities. That’s why they wanted to use the land carefully and wanted to build in height. That was the reason [why] China said: »The lift industry is a priority. [...] We need the land because the cities are getting big. We need to supply the cities from close by.« [...] There was no transport infrastructure in China at all. Self-sufficiency was the priority.‹47 This demand for lifts made Schindler one of the few joint ventures that could sell the majority of its production on the domestic market48 – and still does today.

Schindler opened a new JV in Shanghai.

(picture-alliance/dpa/Weng Lei)

4. China’s Growing Export Market

Other Swiss enterprises, like the chemical and pharmaceutical company Ciba-Geigy, which was created from a merger between Ciba and Geigy in 1970 and is now part of Novartis, were more affected by the export policy. Ciba-Geigy’s first concept for a JV agreement was rejected by the Chinese side due to its strong focus on the Chinese market.49 At this point most of the company’s divisions viewed an expansion to China with distrust, due to the export provisions, but also because of the lack of patent rights.50 But some divisions, especially the Hong Kong Dyes & Chemicals Division, exerted pressure on the executive committee in Basel ›to be in [the Chinese market] from the beginning‹.51 Nevertheless Ciba-Geigy’s executive committee hesitated to give Hong Kong the green light.52 Finally, it was the Pharma Division which managed to set up the first JV in 1988, with the Beijing General Pharmaceutical Corporation. The Zhong-Rui Ciba-Geigy Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd was the first JV between Switzerland and China in the pharma industry and the fifth in total.53

The fact that Ciba-Geigy’s first JV was in the pharma sector may seem surprising, as the company’s own analysis of the Chinese market predicted hardly any sales. Only a small fraction of the Chinese population had access to hospitals and could be reached by Ciba-Geigy’s medical products.54 Moreover, the PRC had developed its own pharmaceutical industry during its nearly thirty-year period of self-reliance.55 The Chinese government’s approval confirms that its main interests were knowledge transfer and accumulating foreign currency. There was no contractual export quota for the JV but, like most other JVs, the Zhong-Rui Ciba-Geigy Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd had to earn hard currency.56

This was difficult for Ciba-Geigy as it needed raw material worth around USD 4 million. So Pharma Division leaders discussed various proposals. The easiest but least economical option was to exchange foreign currency in what were called swap centres, which were centres in special economic zones (explained later in this section) where foreigners could trade currencies under market conditions. They existed in parallel with the official exchange rate system in China and were a government measure to facilitate the balance of trade for the JVs.57 While most of the JVs in the industrial sector struggled with their balance of trade, most of those in the tourist sector achieved a foreign exchange surplus,58 as the number of international tourists in China rose from 187,000 in 1978 to 1.78 million in 1992.59 China’s reform policies opened the country to international and domestic tourism, which had been severely restricted under Mao for foreign policy and ideological reasons respectively. In addition to growing tourism, hotels often served as the first office space for foreign entrepreneurs in the early 1980s. Enterprises like the Swiss company Mövenpick expanded with hotels to China to secure a share of the new market. Their main foreign exchange outflow was salaries for the expatriates. The first Mövenpick hotel, the Dragon Spring in Beijing, employed around five managers from Switzerland on the top level and another twenty managers from Hongkong on a lower level, as a former Board member of the Dragon Spring explained in an interview.60 The other approximately 300 employees were from China. Compared with enterprises like Schindler or Ciba-Geigy, this was a high ratio of expatriates. But as the hotels had a permanent inflow of foreign currency from its customers and less equipment to import, they normally had a positive foreign exchange balance. However, the swap centres brought a surcharge of 25-30 percent and were therefore only seen as a last resort for foreign currencies.61

Other proposals were barter transactions, which would have acquired the necessary resources but were an elaborate procedure compared to monetary transactions. The easiest solution was to buy pharmaceutical raw materials in RMB, and export them to the parent company in Basel in USD, or to buy other non-chemical goods in RMB and export them in USD via trading companies.62 Finally, Ciba-Geigy applied for a trade license from the MOFERT and searched for goods in China it could sell abroad. Most of them, especially natural resources, were subject to export restrictions. Still, in the end, Ciba-Geigy found some other enterprises which agreed to export goods in its name.63

With the balance of trade, the Chinese government forced JVs such as the one with Ciba-Geigy to export through their own networks. Thus, instead of simply opening up its own domestic market, China forcefully integrated itself into the global production chain and became known as the world’s factory. Between 1978 and 2005 its share of foreign trade – the value of imports and exports to gross domestic product (GDP) – increased from 10 to 63.9 percent.64 By 1985, petroleum was China’s largest source of export revenue, accounting for 20 percent. While exports of natural resources decreased, exports of labour-intensive goods increased massively.65 This rise was mainly achieved through FDIs, mostly in the form of JVs. China’s domestic industry was only involved in expanding its export industry to a small degree.66

This construction of an export market was also visible in the development of special economic zones (SEZs). The term ›special economic zone‹, the first of which was set up in Puerto Rico in 1947,67 was distinct from the same phenomenon in Taiwan and South Korea.68 These were zones within states in which special sets of laws applied. Industrialising countries tried to attract foreign investment and production into these zones with low taxes, tax holidays,69 and cheap labour.70 The concept of SEZs was not new when China opened its first four zones in 1978 (in Shantou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Xiamen); it was part of a worldwide trend. According to the International Labour Organization, the number of SEZs rose from 79 in 25 countries in 1975 to 3,500 in 130 countries in 2006.71

For the Chinese government, such zones brought the opportunity to experiment with its economic reforms in locally delimited areas. These zones were especially attractive for foreign investors in the early 1980s due to their lower taxes, better transport infrastructure, and high numbers of cheap workers, who migrated to the SEZs in search of new jobs in the wake of reforms in the agricultural sector. The SEZs were also the first places where enterprises could set the wages of their employees or fire them,72 whereas the rest of China retained the principle of the ›iron rice bowl‹, which meant guaranteed lifetime employment.73

The main difference between China and other countries, however, was the pace at which the SEZs spread. In the beginning, the four SEZs were designed as places where the government could try out new ways of economic activity. In 1984, the government declared fourteen additional coastal cities as special zones. Later, the island province of Hainan and three other coastal zones were also added.74 And although the SEZs initially consumed more foreign currency than they earned, the concept proliferated quickly.75 In 1990, over 25 percent of provinces already had SEZ-like zones and, by 2008, such zones existed in 92 percent of cities.76 Almost the entire coastal region became a special economic zone.77 Aside from this local profusion of zones – in which the Chinese economy could accumulate more and more labour-intensive products, especially in light industry – there was also a trend towards more high-tech production in China, especially in the Shenzhen SEZ, with companies like Huawei and Foxconn producing telecommunication equipment and other electronic goods.78 The accumulation of know-how and foreign exchange has enabled Chinese entrepreneurs to penetrate other markets with their own products and investments, as outlined in the next sections.

5. China Going Global Since the 2000s

The economic context that facilitated Chinese company globalisation in the early 21st century is well documented. After implementing its reforms, China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 and the government gradually shifted its priorities from the ›attracting in‹ (yinjin lai) of foreign capital and technologies to the ›going out‹ (zouchu qu) of Chinese companies. This paved the way for Chinese firms to go global.79 The SEZs often served as cradles for new companies, including private ones. Both private and state companies adopted the ›going-out‹ policy, first to the Global South and, since the mid-2000s, increasingly to Western countries. The 2008 global financial crisis triggered this. The Euro debt crisis made it easier for China to buy Eurobonds and invest in European infrastructure projects.80 In the digital field, the crisis, alongside the burst of the Internet bubble, led the Chinese government to realign its ICT sector, which was then oriented toward the ›going out‹ of Chinese products, technologies, standards, and services, to improve China’s position in global production and value chains.81 The 2013 Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launch underlined this. Subsequently, in 2015, Chinese investments abroad exceeded FDI in China for the first time.82

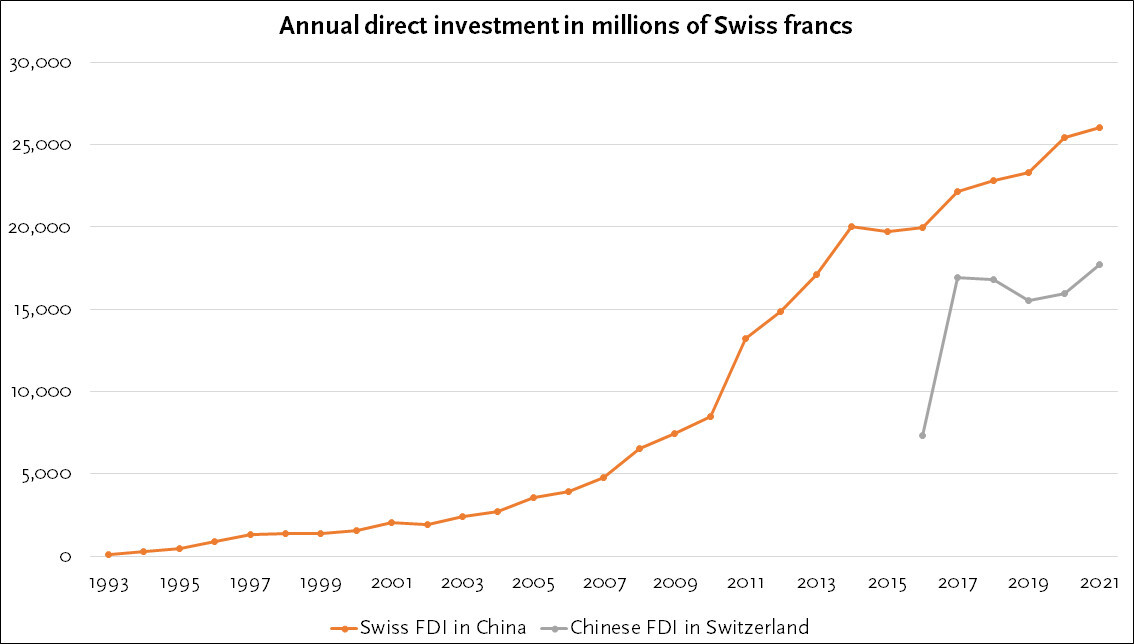

These Chinese investments are mainly concentrated in the Global South, while North America, Western Europe, Japan and South Korea have higher investments in China than the other way round. Switzerland is no exception, with the annual flow of FDI from Switzerland to China being higher than vice versa.83 Notable Chinese investments in Switzerland began around 2016 and reached about 17.7 billion Swiss Francs (CHF) in 2021. This constituted only a minimal share of the total Chinese outward FDI in 2021 – close to 1 percent.84

There is a discrepancy between data from

the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB), likely due to the NBSC considering only ›actually used‹ FDI.

The NBSC does not provide specific information on Chinese FDI in Switzerland.

(graphic by Niklaus Remund based on SNB, Direct Investment, 2023, 3 August 2023, URL: <https://data.snb.ch/de/topics/aube/doc/explanations_aube_fdi>;

for a correction, please see our update)

Chinese companies’ globalisation motivations and strategies differ, depending on specific host regions and company types.85 In Western Europe, including Switzerland, four strategies have become common. First, since the 2000s Chinese companies have established JVs abroad; for example, Huawei’s founding of a JV with Siemens in Germany in 2004 was a first step into Western Europe.86 Accessing foreign markets, brands, talents and technologies are also motivations. As Chen (p), a Huawei cadre, stated in 2022: ›If you want to become number one, you need more talent.‹87 Simultaneously, certain Chinese technologies, such as 5G network technologies, have gained global competitiveness. Thus, European partners are increasingly interested in Chinese JVs in Europe.88

Second, the growing wealth of large Chinese firms and favourable policies in China have facilitated investments and takeovers of European companies. In Switzerland, Chinese takeovers often imply acquiring technological know-how in fields like pharma, medtech and biotech.89 ChemChina’s 2016 takeover of the Swiss agrochemical Syngenta – the largest ever by a Chinese company – is a case in point.90 Syngenta is one of over 130 Chinese-owned companies in Switzerland.91 Chinese investment is growing rapidly, despite a slowdown after 2016. Although most FDI in Switzerland still comes from the US and the EU,92 Chinese acquisitions have raised significant concerns.93 Historically, this is rooted in the ›yellow peril‹ ideology of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western scientific discourses on race, which depicted Chinese and Japanese people as a threat.94 With growing Chinese investments abroad, particularly in Africa in the early 2000s, this ideology fed into media and policy discourses about Chinese ›neocolonialism‹ and ›new imperialism‹.95 Chinese infrastructure loans and investments along the BRI, including ports in Greece, Sri Lanka, and Djibouti,96 further intensified these discussions. This coincided with Chinese strategic take-overs of European and American high-tech firms (whether attempted or completed) in the late 2010s.97

Third, Chinese listings on Western stock exchanges have increasingly targeted Switzerland. In July 2022, the SIX Swiss Exchange and stock exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen launched the ›China-Switzerland Stock Connect‹ programme. As of January 2025, seventeen Chinese companies have been listed on SIX. These are domestically leading companies operating in sectors such as recycling, batteries, pharma, chemicals, carbon, tools and machinery.98 Further companies announced that they would follow suit, allowing them to accumulate capital abroad whilst avoiding domestic capital controls.99 Amid Sino-US tensions and increasing hurdles on US stock exchanges, Switzerland has become a favoured destination for Chinese listings in Europe. The listed companies want to expand, e.g. with factories in Europe, anticipating potential supply chain disruptions related to geopolitical insecurities.100

Fourth, establishing branch offices as well as research and development centres abroad has been common since the late 2000s. The digital infrastructure sector is a prime example. Once reliant on imported technologies, in the past two decades Chinese network technology producers have become global market leaders in this arena. Simultaneously, related technologies and companies from China have become hotly contested and thus difficult to study.

6. Chinese ICT Companies in Switzerland

Our research on Swiss-Chinese economic entanglements began in early 2019. Since then, Chinese companies have continuously expanded, while the Sino-American trade war and debates around Chinese companies have gained pace and continue today.

Relevant companies include, first, the network provider Huawei. The company from Shenzhen was founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, who spent part of his career in the People’s Liberation Army. The US and Western European weapons embargo after the Tiananmen protests provided fertile ground for Ren’s company. In 1994, Ren met then-president Jiang Zemin and convinced him that China should rely on domestic telecommunication technologies. Subsequently, Jiang rolled back existing JVs in the field and supported Huawei and its state-owned competitor ZTE (Zhong Xing Telecommunication Equipment Company Limited) through participation in state projects, subventions, credits, land leases and tax reductions.101 Huawei’s global expansion included stops in Hong Kong, Russia, South America, and eventually Western Europe. Huawei established a branch in Switzerland in 2008 – later than elsewhere in Europe –, winning a tender from Swisscom, the former state monopoly.102 In 2016, Huawei’s business expanded significantly, winning major customers including Schindler.103

Second, the three Beijing-based SOEs – China Unicom, China Telecom, and China Mobile – launched the first fibre optic connections between Europe and China in 1997, in collaboration with partners such as Deutsche Telekom.104 In the early 2000s, Hong Kong and London, historical financial and telecom hubs, were important steps towards settling in Europe.105 In 2016,106 2018,107 and 2020,108 the three cable providers established Swiss subsidiaries.

Third, Alibaba Group, founded by former English teacher Jack Ma in Hangzhou in 1999, is best known for its ecommerce and financial infrastructures. In 2014, the company’s stock launch on Wall Street was the largest in US history. During the ongoing Sino-US trade war, which began in 2018 under the first Trump administration, Alibaba was put on a delisting watchlist.109 It is about to split into six companies, due to a government crackdown on tech companies, following Ma’s open criticism of financial policies and the growing market and discourse power of large tech companies such as Alibaba.110 In the corporate sector, the subsidiary Alibaba Cloud competes with Huawei in cloud computing. In Switzerland the company partners with the Swiss Green Data Centre and China Unicom. It officially opened an office in Bern in November 2023,111 following an ostentatious launch event in Bern’s prestigious Hotel Schweizerhof.

Finally, Xiaomi has been registered in Switzerland since spring 2021.112 Multi-billionaire Lei Jun co-founded this consumer electronics company in 2010 in Beijing, competing with Huawei in mobile phones. In 2021 it became the world’s second-largest smartphone producer, after the South Korean company Samsung.113

All of these Chinese companies have become a geopolitical battlefield and faced various allegations, especially in the US. Huawei, in particular, is at the centre of a debate around banning Chinese telecom equipment in Western countries. This is based on the company’s alleged close ties to the Chinese party-state, which could use Huawei equipment for espionage and sabotage. Although Huawei (like Alibaba and Xiaomi) are private companies, the distinction between SOEs and private companies is not always clear-cut.114 Moreover, the Chinese National Intelligence Law115 implies that Chinese companies abroad might potentially be required to hand over data to Chinese national intelligence organisations, whilst the Chinese Cybersecurity Law requires network operators to ›provide technical support and assistance to public security organs and national security organs‹.116

Geopolitical rivalries, especially between the PRC and the US, have exacerbated concerns about Chinese technology companies, which has also affected Switzerland. While the US government has implemented tariffs and trade barriers to curb Chinese high-tech advancements, US diplomats have exerted pressure on the Swiss government to avoid using Huawei technologies.117 Nevertheless, to date, Chinese ICT companies can all operate freely in Switzerland and debates there are less heated than in other Western countries. In mid-2021, the Swiss government even prepared to outsource state data to Alibaba, alongside four US cloud providers. This sparked a public debate about the use of foreign cloud services, particularly from a Chinese company, and a citizen’s lawsuit was filed that demanded that the Swiss government stop procuring cloud services from foreign providers.118 While this debate has cooled down, taken together, the tensions around Chinese companies make qualitative-empirical research on these companies challenging.

Even without the ›China factor‹, researching fibre optic networks is not easy, as these infrastructures remain largely hidden under the ground and in oceans.119 In Switzerland and elsewhere, they are considered critical infrastructures that require protection and a certain degree of secrecy. Thus, representatives from Swiss telecom companies were reluctant to share any network maps. Visiting a telecom central office, where local lines connect to wider networks, required special permission. So did looking at underground cable ducts that contained sensitive network equipment, including some from Huawei. As a project manager from Cablex, a network construction company, confided: ›We install [Huawei devices], but we are not allowed to open them and look inside.‹120 During an industry fair in Baden, another company was advertising manhole covers with fire protection and defence against Molotov cocktails – as the vendor stressed –, concealing telecom equipment beneath them.121 Visitors at data centres were required to undergo a strict security check. Taking photos was forbidden.122

Under these circumstances, as well as more general secrecy common in the competitive technology sector, our interlocutors were careful not to disclose sensitive information. During one interview on the collaborations between Huawei and Swiss universities, for example, the first thing a Huawei Research Centre representative stated was: ›I cannot tell you very much.‹123 His colleague Mrs. Wang (p), a high-level technical officer in the company, stressed several times that ›we [Huawei] are not trusted‹.124 Chinese ICT companies therefore strategically counter the atmosphere of geopolitical rivalries and mistrust.

7. Chinese Companies Trying to Win Trust

Trust is crucial in international business relationships, requiring effort to establish and sustain.125 In response to the allegations and rivalries mentioned above, Chinese company representatives have crafted a counter-narrative to address the mistrust they face. These entail on-the-ground strategies at the company and customer levels. Companies like Huawei had to devise these when they were still unknown, to enhance everyday trust and intercultural understanding. When Huawei set up a Swiss office, their visiting engineers could hardly speak English and communicate with Swiss customers. Mrs. Wang (p), who was part of the founding team, remembered: ›We had to act as a bridge [... and] do a cultural exchange and integrate body language‹ in intercultural workshops.126 Mr. Schmid (p), a Swiss Huawei manager who previously worked for Swisscom, recalled that, during these events, the Swiss and Chinese sides ›talked about culture, food... We sang »Frère Jacques« and »zhu ni shengri kuaile« [Happy Birthday to You] in Chinese.‹127

Nowadays, explained Mr. Schmid (p), such grassroots intercultural workshops are no longer necessary because the company is well known and has acquired local knowledge. According to our observations and several interviewees, most employees speak English. Those recruited from Switzerland and who have studied there or married locals also speak German or French – although, as Mrs. Wang complained, in everyday life people in Switzerland speak Swiss German, but ›foreigners don’t speak Swiss German!‹ Meanwhile, the company rotates employees from China on four-year assignments, which means that they lack the time and immersion to learn local languages. According to one former Huawei employee, the company rotates its expatriates to prevent them from becoming too immersed in the host society and leaving the company once they obtain a residence permit. In her view, Huawei wants them to work exclusively for the company and be there for the company.128 Similarly, one Swiss sales manager simply waved off the question of learning Chinese, while Mr. Schmid (p) remarked: ›With my [demanding] job at Huawei, it’s simply not possible to learn the [Chinese] language on the side, even though I used to practice my 500 Chinese character flashcards in the evenings.‹129 Therefore, English is the main language of intercultural communication in the office and between Swiss clients and the headquarters. The increased use of English, facilitated by the recruitment of staff from different nationalities in its subsidiaries, has added to the internationalisation of the company. ›We no longer need translators‹, remarked one customer.130 This, along with his annual trips to the Chinese headquarters, has improved intercultural understanding and trust.

In today’s tense geopolitical atmosphere, it is more pressing for Chinese ICT companies to build trust on a higher level, performatively and during public events. They do this by employing Europeans who know the local market and speak out in favour of the company in public. For instance, during a business event in Bern, a British China Unicom representative stressed that ›we have local product managers, service teams, etc. in Europe‹.131 During an online Huawei anniversary event, Spanish Huawei manager Mr. Garcia (p) publicly identified with the company, while his identification with his home country seemed to fade into the background. He even went so far as to claim: ›Europe invited us [Huawei] 20 years ago […] we are part of Europe, our hearts, families are Europe!‹ He explained that ›China [i.e. Huawei’s business in China] is managed by China [i.e. by a Chinese management], Europe is managed by Europe‹.132

However, at least in Switzerland, Huawei’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is Chinese, and Mrs. Wang (p) stated that major decisions typically involve consultation with the headquarters in Shenzhen.133 Over the years, the branch has benefited from a mix of around 400 employees from 30 countries, mainly from China, Switzerland and other European countries.134 The Chinese employees communicate technical details with the headquarters and the Swiss employees manage Swiss customer relationships. Moreover, Mr. Schmid (p) claimed, ›local Chinese‹, such as emigrated families and Chinese women with Swiss husbands, have played an important role in bridging linguistic and cultural barriers.135 This is also because of the rotation system. As Mrs. Wang (p) stated, Huawei Switzerland’s last CEO ›was the only one who stayed for a second term. They [i.e. headquarters] exceptionally kept him in place because of the geopolitical situation‹.136

At Huawei’s public online 20-year European anniversary event in 2020, futuristic, celebratory music and a black background with shining stars accompanied the presentations. Mr. Garcia (p) portrayed the company as European. Displaying photos of sightseeing places like a Christmas market, the Eiffel Tower and the Colosseum, alongside the slogan ›We are Europe‹, he tried to dispel any potentially negative connotation connected to the company’s Chineseness. Similarly, the ›Guest Cow‹ at the Huawei office in Zurich described in our introduction underlines an image of Swissness.

The Sunrise-Huawei 5G Joint Innovation Centre in Zurich (today: Joint Innovation Hub) has a life-size artificial cow, too, standing on green plastic grass next to a milking stool. Maps of 5G expansion in Switzerland are displayed in the background. Instead of the customary bell, the cow wears a 5G necklace, like those being tested in a 5G pilot project that aims to monitor Swiss cows’ health and breeding cycles to produce more milk. Milk is a key ingredient in Swiss cuisine, contrary to most parts of China. Hotly contested 5G mobile technologies are thus linked to a Swiss use case that speaks directly to people’s everyday lives in Switzerland. This and further use cases are shown to Swiss politicians and other visitors to the centre to ›educate‹ and convince them of 5G’s utility.137 It is difficult to imagine that Swiss managers in China would present their company to a Chinese audience based on the same marketing strategy, which draws on local symbols and imaginaries as a way to oppose mistrust.

During their product presentations, the Chinese ICT firms’ representatives in Switzerland repeatedly stressed positively connoted catchwords such as ›sustainability‹, ›green‹, ›innovation‹ and ›trust‹. For example, Mr. Xu (p), a salesman from China Unicom, advertised a VIP ›premium‹ network connecting China and Europe for business customers, which bypasses conventional internet routes. He claimed: ›[…] this is totally separate from the internet, it is private […] you can totally trust this one!‹138 He did not mention though that the cable connecting China and Switzerland largely runs through Russia, relying on collaboration with Russian telecom firms139 – a fact that has gained new geopolitical relevance in the context of Russia’s war in Ukraine. It also applies to other providers operating terrestrial cables – usually owned by consortia of several Chinese and international providers – between China and Europe.140

Meanwhile, Alibaba Cloud manager Mr. Yuan (p) stressed the ›security compliance‹ which the cloud business follows in Switzerland, as well as its ›green cloud technology‹. Moreover, Yuan asserted, ›you could say that I am professionally Swiss-made‹, referring to his doctoral studies in informatics in Switzerland in the 2010s.141 Yuan’s performance may be seen as a strategy for building trust and aligning himself with the industry’s Swiss cultural and technical standards.

In sum, more than two decades after Swiss business activities began in the PRC, Chinese activities abroad have surged since the mid-2000s. These have increasingly triggered and been shaped by geopolitical rivalries, especially in the ICT sector. To explore the gaps between what is portrayed in public and what is not, and what is happening on the ground, we drew on a mix of methods from contemporary history and anthropology. While historical methods are extremely useful for analysing written sources, ethnographic research was mainly possible during industry events and company visits, which aim to display favourable public images. Still, these events, as well as participant observation at network sites and formal interviews, also facilitated informal conversations and glimpses into what is being said and what is not. During these events, our interlocutors talked critically about competitors, former colleagues, and even the Chinese government, and gave insights into their personal backgrounds, health issues ascribed to long working hours, and family lives.

For example, Mrs. Wang (p), who grew up with a socialist ideal of gender equality, claimed that German-speaking Switzerland – known for many women working part-time at most and technical fields being predominantly male – ›was the biggest shock in my professional life‹. In her first management role in a non-Chinese telecoms company in Switzerland, ›nobody talked to me unless they really needed to‹.142 Regarding health, after suffering from back problems, she eventually decided to retire early from Huawei in 2023. Her decision was triggered, she said, by the sudden death of a mid-aged top manager at headquarters with whom she had collaborated closely.143 Another interviewee also left Huawei and, after actively seeking a way to stay, was hired by a Swiss partner company. He explained that he wanted to continue to raise his son in Switzerland, as reintegrating children abroad into the competitive Chinese school system is a major challenge.144 Some Chinese employees, knowing that they would have to rotate and eventually return, deliberately left their children at home with their grandparents. Thus, Chinese company activities overseas appear less as a top-down government strategy, and more as corporate and individual actors – often more concerned with their own lives than with the government or the company – shaping ›Chinese capital‹145 abroad.

This article has focused on Swiss-Chinese economic entanglements since the 1970s. Building on the notion of ›Global China as method‹,146 we have extended the field with Swiss-Chinese case studies and drawn attention to the multi-directionality of the movements of people, ideas, technologies and knowledge. We have explored, first, the history of Swiss companies entering the Chinese market through JVs, highlighting the crucial role Swiss companies played in the history of JVs in China in the 1980s. Representatives from the Swiss companies involved saw the move to China as risky because of a lack of intellectual property rights and the Chinese government’s strong influence. Nevertheless, the risk was downplayed in view of the imagined immense market opportunities for Swiss companies in China. Similarly, human rights concerns appear to be marginal in everyday business contexts, both in the 1980s and today, despite the Tiananmen incident and renewed discussions in the present.

Chinese counterparts, in turn, largely saw JVs as an opportunity to integrate into the world’s production system and acquire crucial technological know-how and foreign currency. Building on and further developing this knowledge has enabled Chinese companies like Huawei to become global market leaders. Here again, JVs initially served as an entry point for Chinese firms to establish their businesses in Europe. Related technologies, knowledge and investments are now making their way back to Europe, and reactions to the influx of Chinese technology have been mixed. We thus turned to Chinese companies going global, in particular to Switzerland. Our focus on the ICT sector shows that Chinese companies in this field have expanded since the 2000s.

Based on these empirical findings, we have suggested that, in order to better understand the past and present of Swiss-Chinese business relations, it is not enough to look at one temporal stage and one geographic direction alone. Taking a longer time span provides a better grasp of dynamics such as technology flows, market integration and globalisation. Moreover, it is not enough to explore China and Switzerland in an isolated way. We have shown that the two countries’ relations must be seen against a broader geoeconomic and geopolitical backdrop, most recently the Sino-American trade war and the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Overall, we have argued for a more comprehensive understanding of Swiss-Chinese entanglements, including creatively combining historical and ethnographic methods. We have suggested that this entangled business history cannot, and should not, be investigated with methods from contemporary history and sociocultural anthropology alone. Instead, a context of geopolitics and restricted access to field sites and archival material calls for a combined methodological approach that draws on both fields. Moreover, this requires a command of the languages and societies under study in order to get below the surface and grasp the multiple nuances and complexities.

Understanding the history of Swiss JVs in China benefits from, among other things, narrative and oral history interviews. These highlight the agency of individual actors below the company level, how these actors make sense of their everyday experiences, and discussions and contradictions between various economic and political actors. While there are overlaps, what is understood by oral history differs in the fields of history and anthropology. In historical research, oral history gained increasing popularity in early post-World War II United States. It also inspired European scholars, who saw this approach as a way to write history from the ›bottom up‹.147 In the history of anthropology, and closely intertwined with European colonialism, oral history emerged as a way to understand the past of ›other‹, oral societies with no written histories, e.g. in the form of collective stories.148 In this article, we have taken inspiration from both interview approaches to explore contemporary corporate histories beyond the official images displayed to the public, and to complement available data gleaned through participant observation and written sources. Our analysis of these written sources, which strongly benefits from the historical methodological toolkit, was helpful for seeing the bigger picture and tracing the history of global company expansions, which is invaluable for contextualising ethnographic case studies and placing them in a temporal perspective.

| Abbreviations | |

| ABB | Asea Brown Boveri |

| AIIB | Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank |

| BBC | Brown, Boveri & Cie. |

| BRI | Belt and Road Initiative |

| CCP | Chinese Communist Party |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CJV | Contractual Joint Venture |

| CROZ | Commercial Register Office of the Canton of Zurich |

| CTE | China Telecom Europe |

| EJV | Equity Joint Venture |

| FDEA | Federal Office of Foreign Economic Affairs of the Swiss Confederation |

| FDI | Foreign Direct Investment |

| FPD | Federal Political Department of the Swiss Confederation |

| FTA | Free Trade Agreement |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| JV | Joint Venture |

| MFT | Chinese Ministry of Foreign Trade |

| MOFCOM | Chinese Ministry of Commerce |

| MOFERT | Chinese Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade |

| NBSC | National Bureau of Statistics of China |

| PRC | People’s Republic of China |

| RMB | Renminbi |

| SECO | State Secretariat of Economic Affairs of the Swiss Confederation |

| SEZ | Special Economic Zone |

| SNB | Swiss National Bank |

| SOE | State-owned Enterprises |

| SOGC | Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce |

| SRF | Swiss Radio and Television |

| USD | US Dollar |

Notes:

1 World Intellectual Property Organization, Global Innovation Index 2024, p. 231.

2 R.A. Meyer, PRC – Ciba-Geigy = Quo Vadis?, March 1979, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, RD 09.1.10_ Volksrepublik China: Praktikanten, Besuche, Reisen, China-Club, p. 25.

3 Michele Coduri/Hans Keller/Eleonore Baumberger, Art. ›China‹, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, 29 April 2009.

4 Ariane Knüsel, China’s European Headquarters. Switzerland and China during the Cold War, Cambridge 2022, pp. 51-53.

5 Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM), China’s Free Trade Agreements.

6 The Federal Council, Direct Trading between Renminbi and Swiss Franc Launched, 10 November 2015.

7 Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Members and Prospective Members of the Bank, 28 April 2025.

8 The Federal Council, President Ueli Maurer meets President Xi Jinping, 29 April 2019.

9 Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of the Swiss Confederation (FDFA), China Strategy 2021–24, Bern 2021.

10 Simon Marti, Bundesrat entscheidet still und leise: Sanktionen gegen China sind vom Tisch, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 30 September 2023.

11 Knüsel, China’s European Headquarters (fn 4); Cyril Cordoba, China-Swiss Relations During the Cold War, 1949–89. Between Soft Power and Propaganda, London 2022.

12 Shichen Wang, Sino-Swiss Strategic Partnership: A Model for China-Europe Relations, in: China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 3 (2017), pp. 267-282; Ralph Weber, Unified Message, Rhizomatic Delivery: A Preliminary Analysis of PRC/CCP Influence and the United Front in Switzerland, in: Sinopsis. China in Context and Perspective, 18 December 2020; Simona A. Grano/Ralph Weber, Strategic Choices for Switzerland in the US-China Competition, in: Simona A. Grano/David Wei Feng Huang (eds), China-US Competition. Impact on Small and Middle Powers’ Strategic Choices, Cham 2023, pp. 85-112. A more comprehensive exception is Ariane Knüsel/Ralph Weber, Die Schweiz und China. Von den Opiumkriegen bis zur neuen Seidenstrasse, Zurich 2024. Most Chinese literature in the past decade emphasises the perceived positive economic effects of the Sino-Swiss FTA, the strategic partnership and the BRI, recently, e.g., Yizhuo Liu, 刘艺卓, 中瑞自贸协定实施十周年:共享开放硕果 [The Tenth Anniversary of the Implementation of the China-Switzerland Free Trade Agreement: Sharing the Fruits of Opening Up], in: 中国外资 [Foreign Investment in China] 9 (2024), pp. 32-35. For consistency, this article lists Chinese surnames after first names, unlike Chinese naming conventions.

13 Rainer Konrad, Chancen und Risiken von Equity Joint Ventures in der Volksrepublik China, St. Gallen 1989; Gunther Veit Strohm, Direktinvestitionen in ausgewählten sozialistischen Ländern unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Equity-Joint Ventures in der VR China, Frankfurt a.M. 1991; Berthold Grünebaum, Marktchance China. Vom ersten Kontakt zum Joint Venture, Frankfurt a.M. 1995.

14 Julian B. Gewirtz, Never Turn Back. China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s, Cambridge, Mass. 2022; Barry Naughton, The Chinese Economy. Adaptation and Growth, Cambridge, Mass. 2018.

15 Ivan Franceschini/Nicholas Loubere, Global China as Method, Cambridge 2022. See also Ching Kwan Lee, Global China at 20: Why, How and So What?, in: China Quarterly 250 (2022), pp. 313-331.

16 Beat Meier (p), interview, 22 April 2024.

17 A planned 2020–21 research stay in China had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All translations of (Swiss) German, French and Chinese sources in this article are by the authors. Interviews were conducted in (Swiss) German and English. Despite our invitation to speak in Chinese, all Chinese interviewees chose English due to their familiarity with it abroad.

18 Laura Nader, Up the Anthropologist: Perspectives Gained from Studying Up, in: Dell Hymes (ed.), Reinventing Anthropology, New York 1972, pp. 284-311.

19 George E. Marcus, Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography, in: Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1995), pp. 95-117.

20 Willy Linder, Chinas Wirtschaft in reformpolitischen Turbulenzen. Rückkehr zur wirtschaftlichen Ratio – spürbare Öffnung, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 18 June 1980, p. 15.

21 Erwin Schurtenberger, Joint Venture, Lizenz- und Kooperationsgeschäfte, Bern 1980, p. 1. Schurtenberger, a key facilitator in the Swiss-Chinese business collaborations at that time, declined our interview requests.

22 S. Dürler/F. Ballmer, China Konzept, 1982, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, PH 8.06.02, Volksrepublik China: Pharma-Geschäft, p. 3.

23 Ibid.

24 Hans Ulrich and Ursula Dätwyler, interview, 17 September 2019.

25 Today: State Secretariat of Economic Affairs (SECO).

26 Letter from the Swiss Embassy in Beijing to Benedikt von Tscharner, 13 September 1978, Swiss Federal Archives, E7110#1989/32#2163*.

27 Renamed the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade (MOFERT) in 1982, today: Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM).

28 This article focuses on equity joint ventures (EJVs), i.e. JVs between two or more companies, whereby a new company is created in the form of a legal entity. An EJV is managed by a board of directors. The number of directors and the profit disbursal arrangements depend on the shares in the company. Another form is a contractual joint venture (CJV), in which no legal entity is created, and responsibilities and profit disbursal arrangements are defined by contract. The focus on EJVs here is due the complexity of the cooperation, which is much higher than in a CJV. There are also other forms of JVs but, if not mentioned otherwise, this article refers to EJVs.

29 Schurtenberger, Joint Venture (fn 21), p. 3.

30 Naughton, Chinese Economy (fn 14), p. 380.

31 lu, Forcierte Erdölexploration in China. Auslandsbeteiligung – Unterstützung für das Reformprogramm, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 6 October 1981, p. 26.

32 fb, Pekings Griff zur Nuklearenergie. Bedeutsames Kooperationsabkommen mit Hongkong, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 28 June 1985, p. 7.

33 Swiss Office of Commercial Expansion, Rapport de Voyage d’une Mission d’importateurs suisses ayant Séjourné à Beijing, Guilin et Guangzhou du 15 au 26 Octobre 1979, Lausanne, 16 November 1979, Swiss Federal Archives, E7115A#1990/60#2240*.

34 Benedikt von Tscharner, Gemischte Wirtschaftskommission Schweiz – China, 27 November 1981, Swiss Federal Archives, E7115A#1991/189#2139*.

35 Swiss Embassy in Beijing to Fritz Honegger, Beurteilung Ergebnis unserer Verhandlungen in Peking im Einvernehmen mit Delegierten der Privatwirtschaft wie folgt, 22 September 1978, Swiss Federal Archives, E2001E-01#1988/16#2597*.

36 Today: Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA).

37 Heinz Langenbacher, China. Kredite und Joint Venture, 24 January 1977, Swiss Federal Archives, E2001E-01#1991/17#5864*.

38 Ann Fenwick, Equity Joint Ventures in the People’s Republic of China: An Assessment of the First Five Years, in: Business Lawyer 40 (1985), pp. 839-878, here p. 842.

39 Alexander T. Mohr, Erfolg deutsch-chinesischer Joint Ventures. Eine qualitative und quantitative Analyse, Frankfurt a.M. 2002, p. 24.

40 Several interviewees mentioned this, e.g. from the Dätwyler company, 29 April 2019.

41 Margaret M. Pearson, Joint Ventures in the People’s Republic of China. The Control of Foreign Direct Investment Under Socialism, Princeton 1992.

42 Today: ABB (Asea Brown Boveri).

43 Marco Müller (p), interview, 24 April 2023.

44 N/A, Handel Schweiz-China, in: Rundschau, 14 September 1984.

45 pmr, Goldrausch-Stimmung in China. Wettrennen westlicher Konzerne um die Gunst der Konsumenten, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 21 October 1994, p. 25.

46 Swiss Office of Commercial Expansion, Republique Populaire de Chine. Rapport de voyage d’une mission d’exportateurs suisses ayant séjourné à Péking et a Shanghai du 24 juin au 4 juillet 1979, 26 July 1979, Swiss Federal Archives, E7115A#1990/60#2240*.

47 Uli Sigg, interview, 7 March 2022.

48 Fenwick, Equity Joint Ventures (fn 38), p. 857.

49 GA, Volksrepublik China – Statusbericht, 7 February 1980, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, RD 09.1.10_ Volksrepublik China: Geschäftspolitik, Reiseberichte.

50 N/A, Aktennotiz über Sitzung des ›China-Clubs‹ betr. V.R. China, 16 August 1979, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, RD 09.1.10_ Volksrepublik China: Praktikanten, Besuche, Reisen, China-Club.

51 Meyer, PRC (fn 2) p. 25.

52 H.U. Ammann, China – Technische Kooperation. FC Projekt ›Quo Vadis‹, 18 May 1979, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, RD 09.1.10_ Volksrepublik China: Praktikanten, Besuche, Reisen, China-Club, p. 2.

53 Peter Achten, Knallfrösche für eine rosige Zukunft…, in: Der Bund, 13 October 1988, p. 22.

54 Dürler/Ballmer, China Konzept (fn 22), p. 1.

55 Ibid., p. 2.

56 Kl, Ciba-Geigy mit Joint Venture in China. Baubeginn einer Pharmafabrik, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 12 October 1988, p. 37.

57 Stephen Bell/Hui Feng, The Rise of the People’s Bank of China. The Politics of Institutional Change, Cambridge, Mass. 2013, pp. 214-218.

58 Pearson, Joint Ventures (fn 41), pp. 137-138.

59 wln, Keine ›Obdachlosen‹ mehr. Ausgebaute Hotelinfrastruktur vorhanden, in: Handels Zeitung, 16 December 1993, p. 48.

60 Elias Fischer (p), Mövenpick, 2024.

61 H. Ruf, Trip Report Hong Kong and People’s Republic of China from 14th – 25th August, 28 August 1990, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, FI 4.01.08_ Sondergeschäfte/Gegengeschäfte mit China, p. 2.

62 Ibid.

63 H. Ruf an M. Angele, China/Viscose Rayon Filament, 17 June 1991, Corporate Archives of Novartis AG, FI 4.01.08_ Sondergeschäfte/Gegengeschäfte mit China.

64 Loren Brandt/Thomas G. Rawski, China’s Great Economic Transformation, in: Loren Brandt/Thomas G. Rawski (eds), China’s Great Economic Transformation, Cambridge 2008, pp. 1-26, here p. 2.

65 Naughton, Chinese Economy (fn 14), p. 393.

66 Nicholas R. Lardy, The Role of Foreign Trade and Investment in China’s Economic Transformation, in: China Quarterly 144 (1995), pp. 1065-1082, here p. 1081.

67 Patrick Neveling, The Global Spread of Export Processing Zones, and the 1970s as a Decade of Consolidation, in: Knud Andresen/Stefan Müller (eds), Changes in Social Regulation. State, Economy, and Social Protagonists since the 1970s, Oxford 2017, pp. 23-40, here pp. 23-24.

68 Jonathan Bach, Shenzhen: From Exception to Rule, in: Mary Ann O’Donnell/Winnie Wong/Jonathan Bach (eds), Learning from Shenzhen. China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, Chicago 2017, pp. 23-38, here p. 25.

69 A tax holiday is a period during which a company is required to pay less tax or no tax at all.

70 Neveling, Global Spread (fn 67), pp. 23-24.

71 Michael Engman/Osamu Onodera/Enrico Pinali, Export Processing Zones: Past and Future Role in Trade and Development, OECD Trade Policy Papers 53, Paris 2007, p. 8.

72 Konrad, Chancen und Risiken (fn 13), p. 72.

73 John S. Henley/Nyaw Mee-kau, The System of Management and Performance of Joint Ventures in China: Some Evidence from Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, in: Nigel C. Campbell/John S. Henley (eds), Joint Ventures and Industrial Change in China, Greenwich 1990, pp. 277-295, here p. 284.

74 Konrad, Chancen und Risiken (fn 13), p. 72.

75 Gewirtz, Never Turn Back (fn 14), p. 101.

76 Bach, Shenzhen (fn 68), p. 30.

77 Naughton, Chinese Economy (fn 14), p. 387.

78 Bach, Shenzhen (fn 68), p. 33.

79 Lutao Ning, China’s Leadership in the World ICT Industry: A Successful Story of Its ›Attracting-in‹ and ›Walking-out‹ Strategy for the Development of High-Tech Industries?, in: Pacific Affairs 82 (2009), pp. 67-91.

80 Philippe Le Corre, Chinese Investments in European Countries: Experiences and Lessons for the ›Belt and Road‹ Initiative, in: Maximilian Mayer (ed.), Rethinking the Silk Road, Singapore 2018, pp. 161-175, here p. 162.

81 Yun Wen, The Huawei Model. The Rise of China’s Technology Giant, Urbana 2020, p. 53.

82 Zhiqun Zhu, Going Global 2.0: China’s Growing Investment in the West and Its Impact, in: Asian Perspective 42 (2018), pp. 159-182.

83 Swiss National Bank (SNB), Direct Investment, 2023, 3 August 2023. See also the graphic. Editorial post-publication note, 10 December 2025: The sentence ›Switzerland is no exception, with the annual flow of FDI from Switzerland to China being higher than vice versa.‹ has to be corrected. More precise is: ›Switzerland is no exception, as its (total) investments in China exceed those of China in Switzerland.‹ In the graphic and its caption, ›annual‹ is wrong.

84 Ibid.; Felix Rosenberger, Länderfiche – Juni 2024. China, SECO, Bern, 28 June 2024.

85 Huiyao Wang/Lu Miao, Ten Strategies for Chinese Companies Going Global, in: Huiyao Wang/Lu Miao (eds), China Goes Global. How China’s Overseas Investment Is Transforming Its Business Enterprises, London 2016, pp. 56-69.

86 Sina, 西门子和华为成立TD-SCDMA合资公司 [Siemens and Huawei Establish TD-SCDMA Joint Venture], 13 February 2004.

87 Chen (p), personal conversation, 2 March 2022.

88 See, e.g., Daniel Hayek/Mark Meili, Getting The Deal Through: Joint Ventures 2021 – Switzerland, 3 December 2020.

89 Jeannette Schläpfer, Chinesische Firmen investieren deutlich mehr in Schweizer Unternehmen, 6 April 2022.

90 Swissinfo, ChemChina Buys Syngenta in Record Chinese Deal, 4 February 2016.

91 In 2023, Switzerland ranked sixth in Chinese corporate transactions in Europe, while Germany ranked first. Yi Sun, Chinesische Unternehmenskäufe in Europa, February 2024 (available after registration).

92 In 2022, Chinese FDI comprised just 2.0 percent of Switzerland’s total FDI that year. Rosenberger, Länderfiche (fn 84), p. 8.

93 See, e.g., Fabian Pöschl, Das alles reissen sich chinesische Firmen in der Schweiz unter den Nagel, in: 20 Minuten, 17 March 2023.

94 Michael Keevak, Becoming Yellow. A Short History of Racial Thinking, Princeton 2011.

95 Ching Kwan Lee, The Specter of Global China. Politics, Labor, and Foreign Investment in Africa, Chicago 2018, pp. 159, 161.

96 See The People’s Map of Global China, Country Archive, 2024.

97 See, e.g., Axel Höpner, Roboterbauer Kuka verschwindet von der Börse – Eigentümer Midea kündigt Squeeze-out an, in: Handelsblatt, 23 November 2021.

98 See SIX, List of Equity Issuers.

99 Finanzplatz, Chinesische Unternehmen an Schweizer Börse machen neidisch, in: finews.ch, 7 March 2023.

100 Matthias Kamp, Immer mehr Firmen aus China drängen an die Schweizer Börse, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 8 March 2023.

101 Kristin Shi-Kupfer, Digit@l China. Überwachungsdiktatur und technologische Avantgarde, Munich 2023, pp. 57-58.

102 Lena Kaufmann, Altdorf – Shanghai – Shenzhen – Liebefeld: Swiss-Chinese Entanglements in Digital Infrastructures, in: Monika Dommann/Hannes Rickli/Max Stadler (eds), Data Centers. Edges of a Wired Nation, Zurich 2020, pp. 262-289.

103 Huawei, Huawei in der Schweiz.

104 China Unicom manager, written conversation, 19 April 2021.

105 China Telecom (Europe), History of China Telecom (Europe); Companies House Gov. UK, China Unicom (Europe) Operations Limited Filing History.

106 Commercial Register Office of the Canton of Zurich (CROZ), Commercial Register. China Unicom (Europe) Operations Limited, London, Zweigniederlassung Zürich, 17 October 2016.

107 CROZ, Commercial Register. China Telecom (Europe) Limited, London, Zweigniederlassung Zürich, 17 May 2018.

108 Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce (SOGC), New Entries China Mobile International (Switzerland) Sàrl, Genève, 19 October 2020.

109 Nicholas Gordon, Alibaba raised $25 billion in 2014 in what’s still the U.S.’s largest IPO. Now a U.S.-China fight could kick the Chinese tech giant off Wall Street, in: Fortune, 1 August 2022.

110 Li Yuan, Why China Turned Against Jack Ma, in: New York Times, 24 December 2021.

111 SOGC, Neueintragung Alibaba Cloud (Switzerland) GmbH, Bern, 30 November 2023.

112 SOGC, New Entries Xiaomi Technology Switzerland GmbH, Opfikon, 30 March 2021.

113 Canalys, Xiaomi Becomes Number Two Smartphone Vendor for First Time Ever in Q2 2021, 15 July 2021.

114 Xinhua News Agency, 中共中央办公厅印发《关于加强新时代民营经济统战工作的意见》[The General Office of the CCP Central Committee Issued ›Opinions on Strengthening the United Front Work of the Private Economy in the New Era‹], 15 September 2020.

115 National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 中华人民共和国国家情报法 [National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic of China], 2017, Article 7, Article 10.

116 Central Government of the People’s Republic of China, 中华人民共和国网络安全法 [Cyber Security Law of the People’s Republic of China], 2016, Article 28.

117 Several interviewees mentioned this, e.g., Mr. Gerber (p), Swiss Fibre Net AG, 1 April 2019.