In 1967, an exhibition opened in East Berlin that proposed, through an overload of images, to unite the histories of the Soviet Union and the GDR, and to confront international photography exhibitions produced in the United States and West Germany.[1] More than the design principles and methods of this show, entitled Vom Glück des Menschen or On the Happiness of People, directly connect it with Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man exhibition, first presented at MoMA in New York in 1953.[2] Its original title was in fact The Socialist Family of Man, and its designers addressed Steichen’s show directly with a scathing critique that echoes the critical discourse in general around The Family of Man.[3] Ultimately, and despite the acknowledged relationship of the exhibition to its Western model, Vom Glück des Menschen also departed from it, crafting a narrative through photographs specifically designed for a socialist society under construction.[4]

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-F1031-0001-010, Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst – Zentralbild, Photo: Hans-Joachim Spremberg)

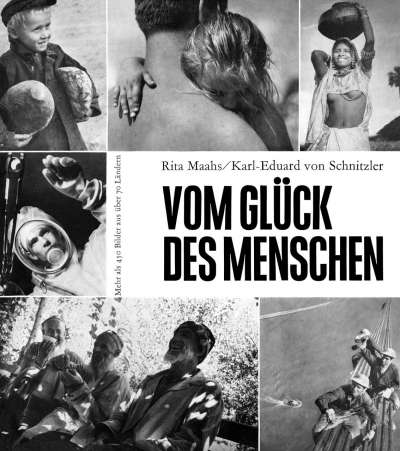

Called ›the first comprehensive thematic photography exhibition of our republic‹,[5] Vom Glück des Menschen was produced under the aegis of the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), Walter Ulbricht, who celebrated its opening with a personal appearance and speech.[6] The exhibition toured within the GDR, visiting Rostock, Dresden, Schwerin, Erfurt, Karl-Marx-Stadt, Leipzig, and Magdeburg.[7] Its Autoren (authors) were Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler, an award-winning journalist, filmmaker, and staunch defender of the GDR’s socialist project until his death in 2001, and Rita Maahs, a writer and photographer who designed numerous photography exhibitions alone and with collaborators, typically with the backing of agencies such as the Federal Worker’s Union (FDGB), the Society for German-Soviet Friendship (DSF) and the Ministry of Culture (MfK).[8]

November 1967

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-F1125-0004-001,

Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst – Zentralbild,

Photo: Rainer Mittelstädt)

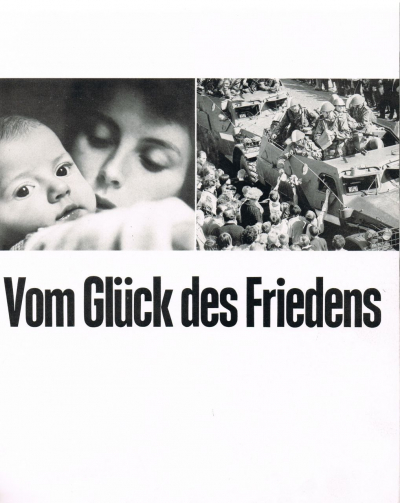

The planning of Vom Glück des Menschen began to appear in the protocols of SED Central Committee meetings in 1965, and a budget was nearly finalized by May of 1967, mere months from the show’s opening.[9] Although Maahs explicitly stated that the catalog was designed to be independent of the exhibition, and that it included more images than the show – some of which were created especially for this publication – we can find the basic structure of the show in its pages.[10] Sections of the exhibition which correspond to Tafeln (movable panels) on which images were grouped are represented in the book, including: Vom Glück der Freiheit (On the Happiness of Freedom), Arbeit (Work), Miteinander (Relationships between people, in this case the new relationship between the classes under socialism), Lernen (Learning), Frieden (Peace), and the final chapter, Vom zukünftigen Glück (On Future Happiness).[11]

The process of developing a concept for the show and then compiling the images began in 1963: Maahs and Schnitzler sent a general call for image submission to 30,000 photographers, photojournalists, amateurs, and photography organizations worldwide, along with 3,000 letters to their personal contacts.[12] The call stipulated the theme as Vom Glück des Menschen, and the format as a Bilddichtung, or photo-poem, and a ›world photography exhibition‹.[13] The goal of the narrative in the introductory text of Vom Glück des Menschen and in the images and shorter texts by Maahs and Schnitzler, Gorki, Lenin, and various other authors, along with historical texts and poems that accompany the long parade of photographs, is to position the GDR in the longue durée Marxist historical model. While the visual narrative sometimes strays from the clear trajectory of the introductory text, perhaps due to the sheer volume of images, the basic message is: the founding and development of the GDR is a direct result of the efforts and goals of the October Revolution, and the GDR has developed according to the model of the USSR. The GDR intervenes in the world as an example and alternative to both the ›slavery‹ of primitive life devoid of technology and of the enlightenment of learning, and to the false capitalist path away from the primitive, which is exploitative and victimizing. Parallel claims are made about the direct relationship between the October Revolution and the liberatory actions of the Red Army at the end of World War II, the advancement of women in the GDR, and the connection between love, relationships, education, technological advancement, and peace in socialist society.

On a superficial level, there are visual similarities between Vom Glück des Menschen and The Family of Man, both of which emphasize individual portraits and scenes of everyday life and families. But Vom Glück des Menschen was not a straightforward imitation of The Family of Man. It was, in fact, a highly engaged critique of the American exhibition, whose embedded criticisms dovetailed, in many cases, with those of such noted critics as Roland Barthes. While Maahs and Schnitzler ambitiously engaged with a predecessor that had exponentially more money and cultural capital at its disposal – the MoMA and, later, the US Information Agency – Vom Glück des Menschen, on its own scale, marshaled a tremendous number of images and put them in a perhaps overly expansive narrative space, both in the catalog and in the exhibition halls where it was shown. However, Maahs and Schnitzler were not only indebted to Steichen, but also to the German tradition of exhibition design. There are, for instance, visual echoes of Weimar-era photobooks in the publication accompanying Vom Glück des Menschen.[14]

While Vom Glück des Menschen was in dialog with The Family of Man, known for its commitment to humanist universalism, this photo-illustrated political tract had a specifically socialist agenda. The exhibition itself was a political tract on display in the form of an exhibition. Rita Maahs was explicit about the authors’ motives, not only in the text of the catalog, but also in an interview with Fotografie magazine editor Alfred Neumann: ›We set ourselves the task of showing in a photography exhibition how the world and its people have changed in the last fifty years. By this we meant that it is time to show the world the socialist family of man on the basis of our worldview.‹[15]

This aim – to show the assumed historical realities of the post-war world according to a particular worldview – flies in the face of Steichen’s claims for universality. It also ironically recalls the famous, scathing essay written by Roland Barthes in response to the version of Steichen’s exhibition that traveled to Paris, called ›The Great Family of Man‹ after the show’s French title. In this review, Barthes excoriated the exhibition as evacuated of history, difference, and thus, meaning. The ›ambiguous »myth« of human community‹ that Steichen had created with his vast array of images of human experience was one that Barthes was keen to debunk. The heart of his critique attacked the absence of History (with a capital H) in this mythological collection of images: ›Everything here, the content and appeal of the pictures, the discourse which justifies them, aims to suppress the determining weight of History: we are held back at the surface of an identity, prevented precisely by sentimentality from penetrating into this ulterior zone of human behavior where historical alienation introduces some »differences« which we shall here quite simply call »injustices«.‹[16]

Barthes’ critique got at one of the major dysfunctions of The Family of Man: as much as images of human commonalities can work to remove the interference of the political, of the historical, as impediments to our belonging in one grand family, they can also provide a screen which conceals injustice. ›These are facts of nature‹, Barthes wrote, ›universal facts. But if one removes History from them, there is nothing more to be said about them; any comment about them becomes purely tautological.‹[17] Barthes rightly interpreted Steichen’s explicit intention – as shown in a statement he had sent to potential contributing photographers. ›We are concerned with the religious rather than religions‹, he had written, ›we are concerned with basic human consciousness more than social consciousness.‹[18]

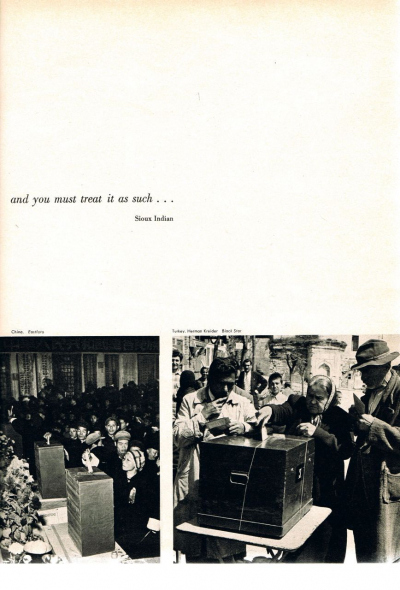

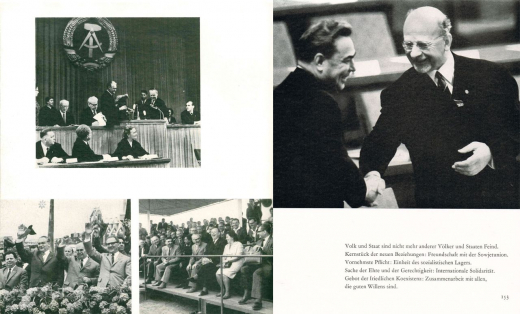

Of course Barthes was not proposing a socialist intervention as remedy. His appeal to ›History‹ and the revelation of ›injustice‹ did not specify a political program, but it is difficult not to hear echoes of his critique in Maahs’ description of the designers’ motives in creating Vom Glück des Menschen. Here was an exhibition that purported to account for the last 50 years of change within the human community. And in adding back ›History‹ to the images of the human family – by making it visible – Maahs and Schnitzler also added back politics, ideology, and of course, ›nation‹. For Steichen, politics mostly appeared abstract and universalized, as in his two-page spread of nationally non-specific images of voters at ballot boxes. For Maahs and Schnitzler, politics was very concrete and specific, as we see in pages featuring the identifiable leaders of the SED.[19]

Like The Family of Man, Vom Glück des Menschen itself became an object of critique within the GDR, as in the April 1968 interview of Rita Maahs by Alfred Neumann mentioned above, and this critique included comparisons to Steichen’s exhibition.[20] Neumann immediately probed the relationship of Vom Glück des Menschen to The Family of Man, and took Maahs to task about its design and execution, implying that the show was too hastily produced and too comprehensive to be readable. Neumann asked: ›Out of more than 23,000 submitted photographs, 770 were used in the exhibition. Isn’t that a relatively large number, an almost unreasonable number, in the sense that the viewer must manage 700 distinct reactions to images?‹[21]

Read together with an unpublished draft of the interview in the archives of the Kulturbund, we learn even more about Maahs’ thoughts on how to understand the exhibition vis-à-vis its Western counterpart. When asked whether she and Schnitzler had examples or models in mind while designing Vom Glück des Menschen, Maahs answered, ›negative ones, we would say‹, and she mentioned both Karl Pawek’s West German Weltfotoausstellung and The Family of Man, decrying them as bad examples of ›world photo exhibitions‹ (due to the underrepresentation of the socialist lands), and taking exception to their rosarot (rose-tinted) depiction of the world.[22] To the question ›Do you include The Family of Man in [your] assessment?‹, Maahs replied quite calmly in the published version of the interview, saying that it did not pursue answers to the question of where happiness comes from.[23] In the unpublished version, Maahs more directly attacks Steichen’s show: ›The Family of Man also! It also gave no answer to the questions: Where does happiness come from? How do people deal with their lives and their world?‹[24] It is safe to assume that the softening of this direct reference to The Family of Man was prompted by the critique marked with the initials of Fotografie editor Gerhard Ihrke, who noted in the margin: ›Was this the goal of Family of Man?‹[25]

In one passage of the interview draft that is omitted entirely from the published version, Neumann asked, ›You wanted to oppose the two above-mentioned exhibitions, then, on the basis of our worldview?‹ Maahs answered that this may seem a bit too utopian in a show purportedly about ›people‹ in general, but that ›the socialist family of man is indeed concrete, visible and describable‹.[26] Not the family of man, but the family of socialism – a family bound together not only by common experiences, but by political ideology. And the visual material of the show reflects this idea: although the nationalities of the people in Vom Glück des Menschen are not easily identifiable, the majority appear to be from the socialist countries – predominantly East Germany and the USSR – and this is echoed in the representation of photographers from these parts of the world.[27]

It is surprising and thought -provoking that the criticism by scholars of The Family of Man closely resembles that of the cultural authorities of the GDR. The most notable photography theorist and critic in the GDR, Berthold Beiler, actually directly echoes Barthes’ critique of The Family of Man, as is pointed out by Jörn Glasenapp and others.[28] The problems of the universalizing statement about the human family and its elision of history are apparent – and were apparent – regardless of which side of the iron curtain one is on, or indeed at what point in history one finds oneself. The East German approach is no less problematic: its universalizing statement applies only to one political project whose dictatorial political conditions were often repressive to the population and which hinges on a black and white comparison with ›the capitalist lands‹, but it does provide a point of comparison that casts light on Steichen’s own elision of ›History‹.

The problem of the erasure of violence in The Family of Man has been addressed by numerous scholars since Barthes’ essay.[29] There is no denying, however, the emphatic absence of the Holocaust and other WWII atrocities in both Vom Glück des Menschen and The Family of Man.[30] In Vom Glück des Menschen, the War is eclipsed by the October Revolution and atrocities in Vietnam. The Vietnam conflict functions as a critique of the West. Rita Maahs pointed out, for instance, that the reason she placed the image of a Vietnamese woman holding her dead child alongside that of an American woman resting next to her newborn was to disrupt the false sense that all was well in the post-war world. ›The happy American mother‹, she said, ›who just gave birth – that would be only half the truth.‹ [31]

World War II exists in this socialist narrative in valorizing images of the Red Army’s invasion of Berlin accompanied by the German translation of a quote from Ernest Hemingway (taken from a Russian article published in Pravda in February 1942): ›Anyone who loves freedom owes such a debt to the Red Army that it can never be repaid.‹[32] There are images of Soviet memorials and a victory parade through Moscow, and of GDR soldiers in front of the Brandenburg Gate as part of a two-page spread with prisoners of war being freed. But there is no sign of the Holocaust here.

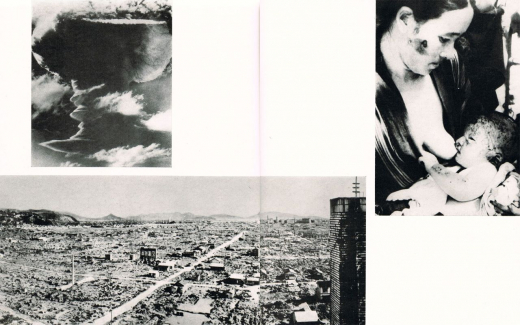

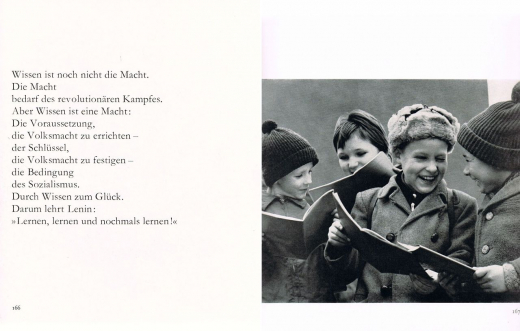

The other impression of World War II in Vom Glück des Menschen comes in the form of the atomic bomb. The huge image of a mushroom cloud, the only photograph in color, had its own room in The Family of Man, though it was excluded from the catalog.[33] However, the bomb has a less abstract appearance in the GDR exhibition, where it is represented in the accompanying book in a two-page spread including a photo of a mushroom cloud alongside images of the flattened city of Hiroshima or Nagasaki and the photo of an Asian woman nursing an injured child. These images are credited only to the GDR’s government photo agency, Zentralbild, so the photographers or the locations cannot be easily identified, nor is there an accompanying text to guide our interpretation. This spread is the penultimate one in the chapter Vom Glück des Miteinander, exploring new relationships between people within the GDR and contrasting images of civil rights protests from the US with photographs of members of the GDR leadership. The atomic bomb images are followed by a cheerful photo of a group of children reading from what appears to be choral music.

Leading into the section titled Vom Glück des Lernens (On the Happiness of Learning), these two spreads seem to propose that the way out of such destructive situations is through the socialist model of educating the Volk. And later in this section, we find another trace of the atomic bomb threat in an image of students at the University of Frankfurt-Main protesting against atomic weapons, below the text: ›There are modern universities in the capitalist lands too. […] The goal of the teaching is a subject that thinks like its master. But fewer and fewer accept this.‹[34] Overall, the treatment of the Second World War and the subsequent nuclear threat in Vom Glück des Menschen is selective, as with The Family of Man, but entirely adapted to its ideological context, using images of violence to support its claims of American destructiveness and West German complicity.

Vom Glück des Menschen was one of hundreds of exhibitions dedicated to celebrating the socialist project of the GDR. What sets it apart is its direct engagement with Steichen’s internationally influential project.[35] The Family of Man and Vom Glück des Menschen belonged to the same milieu, albeit on different sides of its geographical and political divisions. These exhibitions were reactions to the violence and ultimate defeat of fascism, and powerful statements of collective identity during the Cold War. On two different sides of the East/West divide, their methods and degrees of success – both in execution and reception – varied widely. But they are also two sides of a complex international conversation about photography’s role in constructing the identity of a human family across and within national borders. Historically, both exhibitions reveal ideological positions and political blind spots, while at the same time comprising a complex intertextual dialogue about and through photography.

The Family of Man has appeared most often in the historiography of GDR photography as a bland representative of the Western documentary tradition.[36] It is also described as a source of inspiration for photographers such as Evelyn Richter, and for a generation of photographers such as Arno Fischer and Sibylle Bergemann, as well as younger photographers like Gundula Schulze-Eldowy, who amplified the realism in their documentary images of the 1970s and 80s and gained international recognition as the representatives of GDR photography culture.[37] It was these photographers who, according to the usual narrative, would absorb the influence of the West and produce revelatory images that would break through the official veneer of the state-controlled press within the East German dictatorship. These photographers produced incredible images that continue to break through the gloss of socialist propaganda and provide a view of life in the GDR outside the ideological agenda put forth in exhibitions like Vom Glück des Menschen. However, The Family of Man was hardly realism in its highest form. Its influence in the GDR was not confined to the country’s documentary photographers or to Beiler, and this narrative of its influence needs to be complicated.

A large number of GDR citizens saw The Family of Man in person when it was on tour in Berlin. According to Eric Sandeen, of the 44,000 visitors to the Berlin show during its 25-day run in 1955, one fourth to one third of the viewers came from the Eastern Zone.[38] ›On October 7th‹, he writes, ›a holiday in the East, the figure was much higher, including a group of physicians wearing sun glasses to avoid identification by East German observers and the most famous of the East German intellectuals, Bertolt Brecht.‹[39] The show did, therefore, exist to some extent as a lived experience among the East German population. Allowing The Family of Man to enter the discourse on GDR photography only as a positive influence that served secretly to teach and emancipate budding young documentarians, we overlook numerous critiques of the show. And we also ignore the fact that there were unexpected echoes – or indeed even responses – to its statements about universal humanism and American hegemony within the ›official‹ culture of the GDR on the level of exhibition and photobook design: namely, in the form of Vom Glück des Menschen.

Notes:

[1] This article is an excerpt from my dissertation, ›The Problem of the Missing Museum: The Construction of Photographic Culture in the GDR‹, completed in 2015.

[2] For more on this exhibit see Susan Sontag, On Photography, New York 1977; Allan Sekula, The Traffic in Photographs, in: Art Journal 41 (1981), pp. 15-25; Jean Back/Viktoria Schmidt-Linsenhoff (eds), The Family of Man 1955–2001. Humanismus und Postmoderne: Eine Revision von Edward Steichens Fotoausstellung, Marburg 2004; Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World. Photography and Its Nation, Cambridge 2006; Fred Turner, The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America, in: Public Culture 24 (2012), pp. 55-84. This is by no means an exhaustive list. For a good overview of scholarship up to the time of the essay’s publication, see Monique Berlier, The Family of Man: Readings of an Exhibition, in: Bonnie Brennen/Hanno Hardt (eds), Picturing the Past. Media, History, and Photography, Chicago 1999, pp. 206-241.

[3] Alfred Neumann, Sehen, Denken, Diskutieren, in: Fotografie 22 (April 1968), pp. 8-15, here p. 8.

[4] The exhibition has an afterlife in Peggy Mädler’s 2011 novel Legende vom Glück des Menschen (Berlin 2011), in which the book accompanying the exhibition provides both a prompt for the narrator to probe her grandparents’ life histories in the GDR and a governing question and metaphor for the narrative itself: what is the difference between state-mandated and private ideas of happiness?

[5] ›Diese erste umfassende thematische Fotoausstellung unserer Republik‹. Neumann, Sehen, Denken, Diskutieren (fn. 3), p. 8. All translations from German into English are the author’s.

[6] Horst Knietzsch, Erregende Bilder vom Kampf und Glück des Menschen. Walter Ulbricht eröffnete Weltfotoausstellung in Berlin, in: Neues Deutschland, November 1, 1967, p. 1.

[7] In an Umlauf-Protokoll (circulated memo) of the SED Central Committee from May 1967, the original plan for the exhibition’s tour was truncated from stops in all Bezirke (districts) of the GDR to this list of destinations. Umlauf-Protokoll Nr. 3/67, 5.5.1967, Bundesarchiv Berlin (BArch), Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR (SAPMO), DY 30/J IV 2/3/1297.

[8] Schnitzler is best known as the host of the Schwarzer Kanal (›Black Channel‹) program on GDR television. Maahs’ identity appears to have been bound up with the idea of herself as Autorin or Urheberin (Diskussionsmaterial für die Beratung des Sekretariats des Präsidiums am 8. Januar 1974, BArch, SAPMO, DY 27/6692). Her work included collaboration on the first bifota exhibition (Berliner Internationale Fotoausstellung) in 1958 (catalog: Heinz Bronowski, bifota Bilder, Halle 1958), as well as Asien (Leipzig 1963), Frauen der Welt fotografieren (Halle 1964), Liebe, Freundschaft, Solidarität. Eine Bilddichtung (Berlin 1970), and Guten Tag, Berlin. Eine Bilddichtung der Hauptstadt der DDR (Berlin 1981), among others.

[9] Protokoll Nr. 33/65, Sitzung des Sekretariats des ZK vom 3.5.1965, p. 8: ›Fotoausstellung: Durch die Kommission zur Vorbereitung des 50. Jahrestages der Oktoberrevolution, die unter Leitung des Genossen Hager steht, ist die Frage der Durchführung einer Weltfotoausstellung und einer Buchherausgabe »Vom Glück des Menschen« durch Rita Maaß [sic] und Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler zu überprüfen.‹ BArch, SAPMO, DY 30/J IV 2/3/1073.

[10] Neumann, Sehen, Denken, Diskutieren (fn. 3), p. 14.

[11] Rita Maahs/Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler, Vom Glück des Menschen. Eine Bilddichtung, Leipzig 1968.

[12] Ibid., p. 11.

[13] This idea of Bilddichtung – as opposed to an exhibition catalog, photo history, or photography book – recurs throughout Maahs’ descriptions of her work (often as a subtitle for an exhibition or book; see fn. 8).

[14] My dissertation explores in greater detail the indebtedness of Vom Glück des Menschen to such photobooks as Franz Roh’s and Jan Tschichold’s Foto-Auge. 76 Fotos der Zeit, Stuttgart 1929. For Steichen’s own German influences and collaboration with German exhibition designer Herbert Bayer, see Eric Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition. The Family of Man and 1950s America, Albuquerque 1995, p. 44. I also explore the connection between Vom Glück des Menschen and the ›World Photography Exhibitions‹ of Karl Pawek in the dissertation, evident in the use of Bildersätze, or photographic sentences – a term later coined by Timm Starl (›Eternal Man‹. Karl Pawek and the ›Weltausstellungen der Photographie‹, in: Back/Schmidt-Linsenhoff, The Family of Man [fn. 2], pp. 122-139, here p. 129).

[15] ›[…] stellten wir uns die Aufgabe, in einer Fotoausstellung zu zeigen, wie sich die Welt und die Menschen in den letzten 50 Jahren verändert haben. Wir meinten, es sei Zeit, auf der Grundlage unserer Weltanschauung die Welt und die sozialistische Menschenfamilie darzustellen.‹ Neumann, Sehen, Denken, Diskutieren (fn. 3), p. 8.

[16] Roland Barthes, The Great Family of Man [1957], in: Mythologies, New York 1972, pp. 100-102, here p. 101.

[17] Ibid.

[18] STEICHEN – Statement I sent to photographers for show. Edward Steichen Archive (ESA), V.B.i.15, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

[19] The Family of Man also included an image of the U.N., explicitly offering a political stance within Steichen’s universalizing visual narrative (the GDR, for instance, would not become an observing member until 1972).

[20] Neumann, Sehen, Denken, Diskutieren (fn. 3), p. 8.

[21] ›Von den mehr als 23.000 eingereichten Fotografien sind 770 in die Ausstellung aufgenommen worden. Ist das nicht eine relativ große Zahl, eine fast unzumutbare Zahl unter dem Aspekt, daß der Betrachter 700 in sich geschlossene Bildeindrücke verarbeiten muß?‹ Ibid., p. 10.

[22] Ibid., p. 8.

[23] Ibid.

[24] ›Auch »The Family of Man«! Auch sie gab keine Antwort auf die Fragen: Wo kommt das Glück her? Wie bewältigt der Mensch sein Leben und seine Welt?‹ Alfred Neumann/Rita Maahs, Schauen, Denken, Diskutieren [1968]. BArch, SAPMO, DY 27/7581.

[25] ›War das die Zielstellung von Family of Man?‹ Ibid.

[26] ›Sie wollten also den beiden genannten Ausstellungen auf der Grundlage unserer Weltanschauung etwas entgegensetzen?‹ – ›Die sozialistische Menschenfamilie ist doch konkret, sichtbar und läßt sich in Worte fassen.‹ Ibid.

[27] The majority of images came from the GDR (150) and the USSR (87). Surprisingly, West Germany was next with a total of 45. Several communist countries were also well represented, including North Vietnam, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Mongolia.

[28] Jörn Glasenapp, Die deutsche Nachkriegsfotografie. Eine Mentalitätsgeschichte in Bildern, Paderborn 2008, p. 217, as well as Paul Betts, Within Walls. Private Life in the German Democratic Republic, Oxford 2010, pp. 196-197, and Sarah James, A Post-Fascist Family of Man? Cold War Humanism, Democracy and Photography in Germany, in: Oxford Art Journal 35 (2012), pp. 315-336, here p. 324.

[29] Abigail Solomon-Godeau, ›The Family of Man‹. Refurbishing Humanism for a Postmodern Age, in: Back/Schmidt-Linsenhoff, The Family of Man (fn. 2), pp. 28-55, here pp. 31, 33; Viktoria Schmidt-Linsenhoff, Die Banalität des Guten. Zur fotografischen Re-Konstruktion der Menschlichkeit in der Ausstellung ›The Family of Man‹, in: Wiener Jahrbuch für jüdische Geschichte, Kultur & Museumswesen 3 (1997/98), pp. 59-74; idem, Denied Images. ›The Family of Man‹ and the Shoa, in: Back/Schmidt-Linsenhoff, The Family of Man (fn. 2), pp. 80-99.

[30] See James for a thought-provoking challenge to this discourse (A Post-Fascist Family of Man? [fn. 28], pp. 327-329).

[31] ›Die glückliche amerikanische Mutter, die gerade entbunden hat – das wäre nur die halbe Wahrheit.‹ Neumann, Sehen, Denken, Diskutieren (fn. 3), p. 8.

[32] ›Jeder Mensch, der die Freiheit liebt, schuldet der Roten Armee mehr, als er jemals bezahlen kann.‹ Maahs/Schnitzler, Vom Glück des Menschen (fn. 11), p. 90. The complete Russian passage (here in English translation): ›Twenty-four years of discipline and labor have created an eternal glory, the name of which is the Red Army. Anyone who loves freedom owes such a debt to the Red Army that it can never be repaid. But we can declare that the Soviet Union will receive the arms, money, and provisions it needs. Anyone who fulminates against Hitler should consider the Red Army a heroic model which must be imitated.‹

[33] The image was initially hung next to a mirror – presumably to emphasize our universal, shared responsibility for atomic violence, but the mirror, along with the image of a lynched man that Steichen initially included in the show, was later removed. See Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition (fn. 14), p. 50.

[34] ›Auch in kapitalistischen Ländern gibt es moderne Universitäten. Aber wer studiert was? Ziel der Lehre ist der Untertan, der denkt wie sein Herr. Aber immer weniger finden sich damit ab.‹ Maahs/Schnitzler, Vom Glück des Menschen (fn. 11), p. 194.

[35] I would also argue that its most vocal ›author‹, Rita Maahs, and her prolific and sometimes controversial production of exhibitions in the GDR are part of what distinguishes Vom Glück des Menschen. I go into more detail in the dissertation about Rita Maahs as a political and cultural figure.

[36] Kai Uwe Schierz, The Other Leipzig School, in: Susanne Knorr/Kai Uwe Schierz (eds), The Other Leipzig School. Photography in the GDR: Teachers and Students at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig, Bielefeld 2009, pp. 6-15, here p. 9.

[37] This account of The Family of Man’s influence on artistic photographers can be found in Karl Gernot Kuehn’s Caught. The Art of Photography in the German Democratic Republic, Berkeley 1997, pp. 56-57, and Astrid Ihle, Photography as Contemporary Document: Comments on the Conceptions of the Documentary in Germany after 1945, in: Stephanie Barron/Sabina Eckmann (eds), Art of Two Germanys. Cold War Cultures, New York 2009, pp. 186-205, here p. 188. There are exceptions, including Paul Betts’ acknowledgement of Berthold Beiler’s responses to the show in his insightful chapter on the division of photography into public and private modes in the GDR in Within Walls (fn. 28), pp. 196-197. Most notable, however, are Sarah James’ 2012 article and subsequent book, which explore the ›German roots and reception of The Family of Man‹, providing an excellent overview of the connections between Steichen’s project and Germany (post- and pre-war), referring directly to the reception of the show in divided Germany, albeit mostly in the West. There is undeniable validity in James’ project of interrogating many of the dismissive readings of Steichen’s politics on display in the show. I am here taking, in some ways, an opposite and hopefully complementary approach, using the reception and response to The Family of Man in the GDR as a source of further critique of Steichen’s project and grounding my analysis in the East German context. See James, A Post-Fascist Family of Man? (fn. 28), and idem, Common Ground. German Photographic Cultures Across the Iron Curtain, New Haven 2013, in particular the introduction.

[38] Eric Sandeen, ›The Show You See With Your Heart‹. ›The Family of Man‹ on Tour in the Cold War World, in: Back/Schmidt-Linsenhoff, The Family of Man (fn. 2), pp. 100-121, here p. 105.

[39] Ibid.

![Rita Maahs/Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler, Vom Glück des Menschen. Eine Bilddichtung, Leipzig 1968, p. 28 (Photo: J. Mill, Belgium), and Edward Steichen, The Family of Man, New York 1955, p. 25 (Photos: © Nico Jesse/Nederlands Fotomuseum; © 2015 Wayne Miller/Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York)](https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/cumulus/2015-2/Goodrum/resized/1769.jpg)