When the US Army entered Berlin on July 4, 1945, to occupy its sector, the New York Times underlined the significance. ›It will gratify Americans that our troops marched in on the eve of Independence Day‹, read a Times article. ›The liberty which generations of Americans fought and died for could not be celebrated in a more symbolic spot than in the fallen stronghold of Nazi tyranny.‹[1] The occupation of the German capital stood as a symbol of the triumphant victory of the Allied forces over Hitler’s empire. However, this jubilant rhetoric lasted only until Americans began to perceive Berliners as pitiful victims rather than goose-stepping, unscrupulous enemies. Though Tania Long, a German-born American press correspondent who had covered Nazi Berlin until the outbreak of the war, pointed to Berliners’ mental continuities, noting, ›scratch a Berliner and you will find a German‹,[2] their living conditions shocked other Americans. General John J. Maginnis, a member of the local military government, noted in his diary: ›I could sit in my office and say with conviction that these Germans, who had caused so much harm and destruction in the world, had some suffering coming to them but out here in the Grunewald, talking with people individually, I was saddened by their plight. It was the difference between generalizing on the faceless crowd and looking into one human face.‹[3] Only a few years later, Berliners transmogrified again for Americans. By 1949 Berliners – or at least those from the western sectors of the city – emerged as heroic defenders of western values such as ›freedom‹ and ›democracy‹. Most scholars attribute this rapid and astonishing change to the 1948/49 Berlin Airlift that suddenly turned ›enemies into friends‹ and an occupation army into a protecting power.[4]

This article challenges this ›miracle‹ and instead proposes a political and cultural explanation for the rapidly changing reputation of Berliners in American eyes. Taking for granted the often-repeated master narrative obscures two important facets of postwar Berlin. First, in light of their recent experiences with the Soviet occupation, most Berliners eagerly awaited the arrival of American troops. They considered the US Army to be their Schutzmacht, or protecting power, before any American soldier even entered the city. Second, though at no point during the Cold War were the local Allied garrisons actually strong enough to defend the city, their mere presence served as a symbol of the West’s commitment and thereby as an effective deterrent to Soviet military aggression.[5] American military experts nevertheless knew that this unique military strategy would be successful only if the local population supported it. Based on these premises, a bi-national network of occupation officers, politicians, and journalists actively promoted this newly created ›Outpost of Freedom‹. This article analyzes the narration of the history of West Berlin as ›entangled memories‹,[6] a transatlantic narrative that benefited both West Berliners and Americans.

Cities are not just physical, but also imagined places. In fact, contemporaries’ perception and interpretation of a place depends on prior reading and conversation about it. The sociologist Rolf Lindner describes this phenomenon as the physical space overlaying texture that consists of images and texts through which people learn about and experience it. This texture comprises both tangible and intangible cultural representations, including stories and songs, sayings and street names, myths and monuments, films and festivities, anecdotes and advertisings, jokes and urban legends.[7] Together these elements create an imaginary space – or ›spaces of memory‹, as Aleida Assmann suggests – and provide its inhabitants with a unique identity.[8] The city as an imagined place is the result of a social practice that establishes meaning through symbols. It is a social construct that – mostly unwittingly –is created and reproduced in everyday life at the same time that it functions as a catalyst, since the way we imagine a city affects the way we act in it.[9]

As the sociologist Gerald D. Suttles has observed, ›Cities get to know what they are and what is distinctive about them from the unified observation of others‹, which means that the culture of a city can best be examined by ›collective representations whose meaning is stabilized by cultural experts‹. According to Suttles, three ›sets of collective representations‹ generally ›portray the entire community‹: ›The first consists of a community’s founders or »discoverers«. The second includes its notable entrepreneurs and those political leaders, who, by hook or crook, are thought to have added to the community’s »spirit« or »greatness«. The third are not people at all but a host of catch phrases, songs, and physical artifacts which represent the »character« of the place.‹[10] The message of these collective representations mostly is one of a repeatedly challenged but successfully retained ›moral strength‹.[11] The resulting master narrative gets promoted by local ›boosters‹ (›businessmen and political leaders‹), and despite the fact that journalists and writers often question this, ›it is exactly this mix of claims and counterclaims which resolves itself into a residual of defended typifications‹.[12]

This article seeks to outline the textural overlay of West Berlin by analyzing how historic images and perceptions of post-war events together formed the narration of the ›Outpost of Freedom‹, and identifies who promoted this narrative and for what purposes. Berlin’s roles as a turn-of-the-century boomtown and creative hub of the roaring 1920s had left an indelible mark on contemporary observers, who appropriated selected tropes of this past to legitimize truncated West Berlin as the essence of Berlin.

1. From ›the most American city‹

to the ›Outpost of Freedom‹

By the close of the nineteenth century, German and American observers alike characterized Berlin as a metropolis similar to those in North America. [13] Walter Rathenau’s famous quote about the death of ›Spree-Athens‹ and the rise of ›Spree-Chicago‹ illustrates this development.[14] Following the foundation of the German Kaiserreich, the city grew rapidly and attracted both national and international attention. While their new capital’s transition to an economic juggernaut unsettled many Germans, the city drew foreign observers as an example for the contradictions of the Wilhelmine Era. While Berliners had to learn to navigate the effects of industrialization, urbanization, and a newly emerging mass culture,[15] they attracted Americans’ attention for facing the same challenges.

In 1890, Mark Twain confided, ›I feel lost in Berlin. It has no resemblance to the city I had supposed it was. [...] It is a new city; the newest I have ever seen.‹ Widely travelled as one of the first international celebrities, Twain could compare Berlin only to Chicago, a contemporary American eponym for rapid urban growth. Berlin compared favorably to Chicago. ›Only parts of Chicago are stately and beautiful, whereas all of Berlin is […] uniformly beautiful‹, Twain wrote.[16] Even if the Wilson administration later would depict the Wilhelmine Empire as Europe’s authoritarian behemoth, Twain established an enduring American pattern of interpreting Berlin as a metropolis facing challenges comparable to those in the United States. From the fin-de-siècle onwards, a considerable number of American journalists, writers, and activists came to Berlin to use it as a case study of a modern metropolis under an interventionist government.[17]

In the aftermath of World War I, the conception of Berlin as the most American metropolis in Europe became overtly politically charged. Since the United States had become the symbol of modernity at large, a positive interpretation of Berlin as an American city meant embracing it as a cosmopolitan city and heralding international and domestic acceptance of the Weimar Republic. In a less benign interpretation, the continuing growth, increasing number of non-native inhabitants, and allegedly un-German profit-seeking made ›American‹ Berlin a symbol of what ailed German society. Therefore, ›American‹ Berlin’s meaning depended heavily on an author’s embrace or rejection of modernity.[18] To Berliners, this transatlantic comparison offered a new source of inspiration and self-confidence that made them unique, rather than an inferior copy of Paris or London.[19] An event calendar published by the local tourist office in 1922 boasted, ›Berlin is the most modern city in Germany, which means the most American city.‹[20]

World War II and the Holocaust ended Americans’ overwhelmingly positive associations of Berlin. In 1943, Shepard Stone, a US Army intelligence officer who had completed his doctorate in Berlin, commented laconically on Allied air raids on the city: ›Berlin […] received a terrible blow. The University is apparently no more. Well, they asked for it.‹[21] Shortly after the ferocious Battle of Berlin finalized Germany’s defeat, journalists from all over the world came to report on the symbol of the Allied triumph over fascism, the ruins of Berlin.[22] In spite of the destruction wrought by war, American journalists quickly picked up on the remarkably resilient atmosphere of Berlin. The New York Times celebrated Berlin as ›the most polyglot city in Europe‹, delightedly describing how its inhabitants were trying to please their new authorities by translating the names of even the smallest shops and by announcing actors and nightclub artists in the languages of the Four Powers.[23]

After spending a night at the Royal Club, a journalist from the Chicago Daily Tribune rhapsodized that not even Paris showed such elegance – or such pricy restaurants. ›The entire scene was that of Berlin’s notoriously gamey night life between the world wars‹, he wrote, and he was not entirely exaggerating.[24] Within only two years after the war, 5,715 restaurants and bars, 365 cafes, 282 kiosks and ice cream parlors, and 488 hotels and pensions, together employing 28,140 people, had opened their doors to a pleasure-seeking public.[25]

The US Army took up this narrative of Berlin as a worldly, creative, and vibrant parvenu among European cities that once again was proving its international importance. ›Between the two world wars, Berlin, because of its location in relationship to the rest of Europe, became a meeting place of eastern and western influence‹, read a guide to the city published by the Army. ›Its position as an international clearing house of new political, intellectual and artistic ideas steadily grew under the Weimar Republic. Now once again it has become the meeting place of the west and east, this time through the medium of the Allied Military Government.‹[26]

By underlining the city’s democratic and liberal traditions while simultaneously marginalizing the years it had served as Nazi Germany’s capital, American military authorities supported the creation of a narrative directly connecting Weimar to post-war Berlin. In this narrative the Nazi era appeared to have been an unfortunate accident, a system forced onto the open-minded city famous for its progressiveness, its vibrant cultural scene, and its powerful leftist groups.[27] These images of 1920s Berlin served not just as a blueprint for the average American perception after World War II, they also provided a guide for the city itself. The ruins thereby served as placeholders, as a reference to an increasingly mythicized past. Searching for Berlin’s former glamor, journalists, tourists, Allied soldiers, politicians, and novelists continued the tradition of ›urban spectatorship‹, which suggested a historical continuity that tended to soften or even erase the caesura between 1933 and 1945.[28] This reimagining of Berlin did not necessarily mean that American political and military leaders were willing to think of Berlin as their new favorite ally, but it shows how the city’s past provided images and narratives that could be used as a foundation for its new historical role as a symbol of the ›free world‹.[29]

During the Cold War, many different terms were used to describe West Berlin’s unique geographical location and political situation. It was called an ›outpost of freedom‹, a ›thorn in the flesh of communism‹, and an ›island in a red sea‹. Despite the popularity of these metaphors, historians have not been able yet to identify their inventors. But crucially, by 1950 key American personnel in Berlin had become enthusiastic about the city they occupied. A heroic interpretation of Berlin’s history captivated the US High Commission’s own propagandists before they advanced the ›Outpost‹ narrative through radio broadcasts, newspaper campaigns, and pamphlets. As the Public Affairs Bureau, then led by Shepard Stone, briefed US Commandant Maxwell Taylor, ›Berlin before the war was the greatest commercial, industrial and communications center on the continent. […] But it was more than that. For my generations, prior to the creation of the modern German state, Berlin was the cultural and spiritual capital of the German-speaking people. […] It is a cosmopolitan city. Its people have the quality sound in great cosmopolitan centers. They are quick intelligent, possessed of a sense of humor, and contrary to most prevailing ideas in the world, have a long tradition of independence and liberalism. […] Very few know that Berlin resisted the Nazi regime more strongly than any other major city in Germany. Berlin was the safest city in Germany throughout the Nazi regime for hunted liberals.‹[30]

For US authorities in Berlin, the pre-Nazi past determined the present. For a number of American occupation officers such as Stone this interpretation reconciled them with the city they had known intimately. The 1951 annual report of the US commandant called the city ›an outpost of free nations behind the so-called Iron Curtain‹.[31] An internal memorandum written by the Office of the High Commissioner of Germany (HICOG) in 1952 described it as an ›outpost of freedom in the middle of the Communist area of influence‹, a ›focal point of the cold war‹, and a ›show-window of freedom‹.[32] From this time on, these terms would appear constantly in American internal correspondence and speeches given by various politicians, though this hardly proves an American origin of these terms.

(Landesarchiv Berlin, Photo: N.N., F Rep. 290 [02], No. 0255844)

Although many historians believe that Germans willingly adapted this interpretation of their city after the lifting of the blockade,[33] numerous sources point to an earlier provenance. Though the narrative of a grateful and passive population became part of West Berlin’s founding myth, contemporaries insisted on an acknowledgment of their active anti-communist contribution, and American authorities agreed with their point of view.[34] General Lucius D. Clay publicly explained the agreement between the United States and Berlin’s Western Sectors, noting that the US would be willing to support them ›so long as the people of Berlin continue to cherish their freedom and merit the continued support of the American people‹.[35]Clay did not exaggerate the American identification with the city’s fate. In the summer of 1948, shortly after the airlift had started, 80 percent of Americans favored holding on to the Western sectors of Berlin, even if this would lead to another war.[36] However, the US expected not only gratefulness, but active support – and they would not be disappointed. Numerous sources reflect how much American authorities appreciated West Berliners’ cooperation during the initial years of the Cold War. For example, in 1949 the first official directive for the High Commissioner of Germany noted how highly the State Department valued recent events. ›It is the special belief of your government that Berlin, because of the courageous devotion to democratic liberties which its people have displayed, should be permitted an important role in the development of the Federal Republic of Germany‹, the directive read.[37]

The local population and the West Berlin media were very much aware of the benefits of a strong public commitment to the Western powers. On the first day of the blockade, the newspaper Der Abend reminded readers that ›the struggle for freedom and human rights‹ that Berlin had been fighting ›in recent years‹ had led ›the world to hold the city in high regard‹. This newly acquired reputation and international attention were considered to be of great importance, something West Berlin would be able to capitalize on politically.[38] After the Soviets had suspended the blockade, Otto Suhr, the president of the West Berlin city assembly, congratulated General Clay by telling him that ›his work has not been in vain. He has played an important role, so that the Berliners were able to fight their struggle for freedom.‹[39] Contemporaries knew that Berliners in the Western sectors had not survived solely through the immense food rations and other supplies provided by the airlift. They had demonstrated their firmness by breaking Allied laws whenever necessary to get what they needed and by resisting the temptation to leave the city – and they were proud of it. A survey conducted immediately after the blockade that tried to estimate the effect of an exhibition about the airlift on West Berliners’ self-perception revealed that they preferred pictures of their own struggle and fortitude to images of the well-known ›candy bombers‹.[40]

Meanwhile, American authorities described their perception of West Berlin in familiar narrative patterns. In 1950, US-commandant General Maxwell D. Taylor stated, ›Unfortunately, in Berlin we are like the early frontier – every half hour we have to put down our plow to pick up our gun, only we don’t have the Indians up here.‹[41] By comparing the situation in Berlin to westward expansion in the US, Taylor employed the American myth of ›Manifest Destiny‹ to describe his experiences. The importance of the ›frontier‹ for establishing a unique American identity was first stated by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893.[42] His work turned into a popular master narrative because it seemed to prove the nation’s uniqueness, based on the experience of its westward expansion.[43] During the Cold War, the ›Iron Curtain‹ became the new frontier, turning Berlin into an endangered fort in close proximity to the enemy.[44] The American documentary television program The Big Picture accordingly described the city in the early 1960s as ›a frontier of freedom which cannot be abandoned‹.[45]

Despite the frequent use of this term by American officials, it cannot be described as solely an American invention. The first to use this figure of speech in public apparently was the Governing Mayor elect Ernst Reuter, when he implored the people of the world to recognize ›that here in this very city, a bulwark, an outpost of freedom (Vorposten der Freiheit), has been erected which no one could abandon with impunity‹.[46] The mayor’s words reflected the beliefs of most West Berliners. Asked by pollsters to describe their city in 1951, a vast majority identified with this narrative by calling their home town ›an island symbolic of the struggle‹ between East and West, ›a listening-post for the West, the last rampart of the free world and an example to it‹, ›the last outpost of freedom in the middle of the Red Sea‹, ›the bulwark, the dam, for the Western powers – if we fall, Europe falls too‹. Only 2 percent responded that the Berliners would not deserve such a heroic reputation.[47]

(Landesarchiv Berlin, Willa, Johann, F Rep. 290 [02], No. 0076200)

The ›Outpost of Freedom‹ metaphor not only prevailed, but gradually signified a unique German-American narrative that offers a compelling interpretation for Berlin’s history to this day. Although the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 caused some protests against the Allied non-interference policy, it did not have any long-lasting effects on the transatlantic bond.[48] Standing in front of the West Berlin city hall two years later, US President John F. Kennedy declared in his famous speech that the now walled-in audience would be living on a ›defended island of freedom‹ and that Americans would ›take the greatest pride‹ in this shared struggle to uphold this symbol of democracy. ›There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world. Let them come to Berlin‹, said Kennedy.[49] Six years later, in 1969, President Richard Nixon told workers of the traditional Berlin corporation Siemens, ›There is no more remarkable story in human history than the creation of this island of freedom and prosperity, of courage and determination, in the center of postwar Europe.‹[50] President Jimmy Carter, whose visit to Berlin in 1978 is nearly forgotten, articulated an almost mythical bond between West Berlin and the United States by applying America’s ›manifest destiny‹ to the city. ›The Bible says a city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden‹, he began. ›What has been true of my own land for three and one-half centuries is equally true here in Berlin. As a city of human freedom, human hope, and human rights, Berlin is a light to the whole world; a city on a hill – it cannot be hidden; the eyes of all people are upon you. Was immer sei, Berlin bleibt frei.‹[51]

Carter referred to the biblical Sermon on the Mount, a popular American reference that dates back to the Puritan settlers and their interpretation of their mission.[52] Although other presidents did not directly quote the Bible, they invoked similar images and metaphors on a regular basis. President Ronald Reagan, who famously described the United States as a ›shining city upon a hill‹, declared in 1987 that it was every president’s obligation to speak ›at this place of freedom‹, and he praised the ›courage and determination‹ of the West Berliners. ›For I find in Berlin a message of hope, even in the shadow of this wall, a message of triumph‹, he said. ›From devastation, from utter ruin, you Berliners have, in freedom, rebuilt a city that once again ranks as one of the greatest on earth.‹[53]

By framing West Berlin as a symbol to the rest of the world, an exemplary ›city upon a hill‹, American presidents were not just equating the city with the United States, but incorporating it into their own ›imagined community‹ and thereby turning it into a transnational community. What is striking about these presidential speeches and other contemporary accounts is the application of uniquely American narratives and motifs to describe and explain West Berlin.[54] Elements of American cultural memory, such as the idea of a ›manifest destiny‹ to spread the ideals of freedom and democracy, now were used to interpret a German city’s situation and mission.[55]

This new perception and narration of Berlin was widely accepted almost immediately because both Berliners and Americans benefitted from it.[56] The local population benefitted from the military protection guaranteed by NATO and from the special economic support granted by the US to dress up this ›shop window‹ of western democracy and prosperity. Additionally, this narrative provided the city and its inhabitants with a new positive tradition, an identity no longer based on the horrors of the Third Reich. It offered Berliners a place on the right side of history in this renewed fight of ›the West‹ against totalitarianism and retroactively acknowledged their ordeal during the first weeks of Soviet occupation as victims of Communism. This perception of the political situation and the related narrative created a transnational bond and admitted West Berlin to a powerful transatlantic ›imagined community‹ that lasted for several decades.

Berlin gave the United States the opportunity to celebrate its first victory in the struggle between two newly minted superpowers. In a briefing on the current situation of Berlin in 1950, the American head of public affairs explained why holding on to the city was of strategic importance: ›Here, in our Berlin war, our weapons are limited to economic measures and to ideas and words. The vital target in Berlin is the West Berlin population. Our position here rest[s] squarely on the support of this population. If ever should we lose its confidence, our position would become untanable [sic]. You need only to think of the map to realize that if the West Berlin population should ever become rebellious or grow disaffected, it would require divisions where we now have battalions to maintain our position if, indeed, we do it at all. […] Our secondary mission, of course, is offensive, to exploit our position in Berlin to the maximum advantage with information going direct to the Soviet occupied areas and the east sector and, of course, our mere presence here constitutes, probably, the most effective propaganda of this sort that we could contrive.‹[57] Strikingly, American officials remained keenly aware of their reliance on Berliners’ popular opinion despite the rampant triumphalism after the conclusion of the airlift, and therefore consciously pursued policies to retain their support.

Another paper published by the same division added a moral obligation to the mere strategic considerations. ›This battle to maintain an island of freedom behind the iron curtain is important for two reasons‹, it read. ›1., because the West Berliners are worth keeping free, and 2., because West Berlin is a symbol for the rest of the world.‹[58] These statements point out the military and political advantages of a city that was embracing its own occupation. As the journalist and historian Peter Bender wrote, ›You cannot defend a city that does not want to be defended. The West Berliners wanted it.‹[59] In doing so, they confirmed the image of a stoic population that stood up against any Communist threat.

2. The Outpost’s Boosters

The ›Outpost of Freedom‹ narrative’s success also relied on its ability to connect crucial political actors in West Berlin. Tropes of a cosmopolitan and liberal city appealed to the aspirations of three political factions holding most framing power within postwar West Berlin: anti-communist local politicians, local journalists, and US occupation authorities. Moreover, shared subscription to the ›Outpost‹ narrative compelled Social Democratic rémigrés (returned émigrés), young journalists of the Radio in the American Sector (RIAS), and liberal American occupation officials to form a potent political network in its own right. While initially created to counter Communist ambitions, this network demonstrated remarkable cohesion in furthering the agendas of its members domestically as well.

The Berlin Social Democratic Party (SPD) had garnered the respect of the American military government (OMGUS) in March 1946, when the overwhelming majority of Social Democrats, led by Franz Neumann, resisted Soviet pressure to merge with the Communist Party (KPD) to form the Socialist Unity Party (SED).[60] The 1948/49 Berlin Blockade and the administrative split of Berlin prompted close cooperation between US authorities and the governing SPD in West Berlin.[61] For US authorities, this still avowed Marxist party constituted the only political faction in Berlin whose intense anti-Communism matched a tradition of resistance to National Socialism. The irony of such an alliance in the center of the Cold War was lost on both parties, as the shared conviction of defending the ›Outpost of Freedom‹ made it seem like a logical choice, as exemplified by the well-publicized personal bonding between Lucius D. Clay, commander of OMGUS, and Governing Mayor Ernst Reuter.[62] Behind the scenes, this alliance relied on personal contacts that exiled Social Democrats made during the war, and that they continued to exploit after their return to postwar Berlin.

Ernst Reuter and Willy Brandt are the most prominent examples of Social Democratic rémigrés in West Berlin, but Hans E. Hirschfeld best exemplifies the coordination between US authorities, West Berlin SPD, and RIAS to advance the ›Outpost‹ narrative. Born into an assimilated German-Jewish family, Social Democrat Hirschfeld defended the Republic in Prussian state radio broadcasts during the Weimar era. He survived National Socialism in exile, having to flee consecutively from Germany, Czechoslovakia, and France before arriving in the United States in 1940. In New York City, Hirschfeld was active in the scattered SPD-in-exile while working as an analyst in the Office for Strategic Services’ (OSS) biographical records branch.[63]

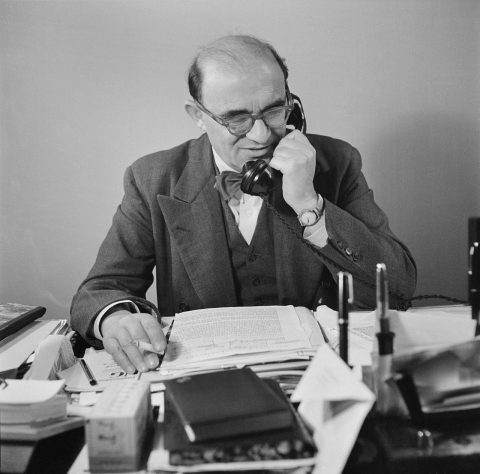

(SLUB Dresden/Deutsche Fotothek, Photo: Fritz Eschen, 1952)

Upon the launch of the West Berlin airlift, the US State Department invited Ernst Reuter to tour the United States.[64] His April 1949 visit proved triumphal, convincing American legislators and journalists that West Berlin deserved considerable American support as the beleaguered ›Outpost of Freedom‹. In New York, Reuter convinced Hirschfeld to return to Germany as West Berlin’s public relations manager.[65] Initially skeptical of the ›Outpost‹ narrative, Hirschfeld described his experience in West Berlin to hesitant New York émigré friends as a kind of divine revelation. ›After a few days in Berlin, Saul became Paul. […] I stayed here, because I am convinced that we in Berlin complete a crucial political mission – unlike anywhere else on earth‹, he said.[66] The conception of West Berlin as the ›Outpost of Freedom‹ gave rémigré Social Democrats like Hirschfeld a new political purpose and the opportunity to justify their return to their estranged hometown.

Hirschfeld tirelessly promoted Reuter’s policy as the defense of the ›Outpost of Freedom‹ to Allied authorities, German journalists, and ordinary Berliners alike. As Reuter’s public relations director and a man on a mission, Hirschfeld continued to cultivate strong personal ties with figures in the United States. Most notably, Hirschfeld used for delicate political ends his personal wartime friendship with the US High Commission for Occupied Germany (HICOG) Public Affairs Director Shepard Stone.[67] Hirschfeld served as liaison between Reuter’s mayoral office and US authorities in pursuit of clandestine funding.[68] Between June 12, 1952, and November 30, 1953, Hirschfeld received a total of 106,500 Deutschmarks in cash from the US State Department for nebulous ›services to be rendered‹, presumably to fund his public relations work advancing the ›Outpost‹ narrative.[69]

Hirschfeld’s work with RIAS further highlights his crucial role in keeping both Berlin Social Democrats and US occupation authorities on message. OMGUS had founded RIAS in 1946 to pursue an independent reorientation policy. The Berlin airlift catapulted RIAS’s popularity to soaring heights – reaching up to 80 percent of all listeners in the Berlin market[70] –, and RIAS continued to hold this commanding position during the 1950s. American authorities regarded RIAS as its most important propaganda outlet in Berlin.[71]

RIAS’s success derived not only from exploiting the airlift,[72] but also from shrewdly adjusting its program to Berliners’ tastes.[73] RIAS’s programming deliberately contrasted with its GDR-run competitor Berliner Rundfunk, which extolled the party line.[74] Its slogan, ›A free voice of the free world‹, exemplifies the duality of RIAS’s competing goals, which were tasked with simultaneously upholding the ideals of independent journalism and furthering a Cold War political agenda. American RIAS management addressed this tension on an ad-hoc basis, with its journalists pushing to expand journalistic freedom while HICOG and the SPD demanded political loyalty.

Despite these constraints, RIAS’s status as a unique German-American hybrid institution conferred liberties as well. Unlike public broadcasting stations in the Federal Republic proper, RIAS did not possess any broadcasting council that guaranteed institutional party representation and control.[75] Under American management, young German broadcasters created a program that combined news, highbrow culture, and entertainment. Eminent West German figures emerged as RIAS journalists, such as Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik confidante Egon Bahr and his speech writer Klaus Harpprecht, political journalist Gerhard Löwenthal, and popular TV host Hans Rosenthal. Through its pioneering programming, RIAS stood out to an audience conditioned by twelve years of Goebbels’s broadcast indoctrination.

The lack of institutional control prompted SPD attempts to influence RIAS programming through informal networking. Again Hirschfeld proved influential when he sought preferential RIAS coverage of the Berlin SPD, especially of members with an exile background. Hirschfeld built a close relationship between US authorities, SPD rémigrés, and RIAS based on personal trust. Newly in office, he introduced Reuter to the incoming RIAS Director Fred G. Taylor on the day of his arrival. Taylor agreed with Hirschfeld’s agenda, as he had already discussed the ›shared work‹ between them.[76] In 1950, Taylor asked Reuter to ›rest assured that RIAS will always strive to support your work in every regard‹.[77] By referring to the city as ›our Berlin‹, Hirschfeld indicated to his ›dear friend‹ Taylor that the creation of West Berlin was a Social Democratic and American co-production.[78]

The intense cooperation between SPD rémigrés, RIAS, and US authorities enraged their shared political rivals on the other side of the Brandenburg Gate. East Berlin’s SED regularly denounced RIAS journalists as mercenaries serving the United States. But behind closed doors, the SED party bureaucracy begrudgingly admitted that ›the hate and slandering campaign of the West press and RIAS succeeds in confusing many West Berlin workers who hence still disapprove the Workers’ and Peasants’ Might to the benefit of the rémigrés faction in the SPD‹.[79]

Prominent German politicians were not alone in trying to sway RIAS’s editorial line. Between 1953 and 1955, both the McCarthy and Eastland committees ›investigated‹ RIAS, which took its toll on employees. In 1955, the Eastland committee interrogated Charles S. Lewis, who had initiated RIAS nine years earlier, as he had been associated with Communist circles for a short period in 1937. Lewis testified before the Senate committee that he felt pressured to step down from his post overseeing all US radio operations in Germany when he learned that ›loyalty charges‹ were to be pressed against him.[80] In a private letter to Hans Hirschfeld, Lewis recounted this experience. ›I need not tell you, Hans, that being turned inside out by a Senate committee is far from pleasant‹, he wrote. ›There must be an easier way to be purged, I hope it will be found for others in a similar situation.‹[81]

Lewis’s case demonstrates how allegations of leftist sympathies still affected the careers of people associated with RIAS even after Senator McCarthy was censured in 1954. Before this, these allegations clouded the entire station’s future. In April 1953, Roy Cohn and G. David Shine, McCarthy’s most notorious aides, descended upon West Berlin as part of their investigation of the United States Information Services (USIS), to whom RIAS reported. Roy Cohn accused USIS operations in Berlin of ›wasting millions worth of dollars on waste and mismanagement‹ and having former Communists on its payroll.[82] Two months later, on June 18, 1953, McCarthy announced his intention to summon to his Senate committee Gordon A. Ewing, Political Editor at RIAS.[83]

The timing of this investigation had been astonishing. A day earlier, on June 17, 1953, East Berlin erupted in a popular uprising that was quelled violently by Soviet tanks. The GDR leadership quickly blamed RIAS for having orchestrated the uprising, and Ewing in particular.[84] In spite of these dramatic developments, McCarthy’s allegations jeopardized Ewing’s career and reputation. Ewing sarcastically asked Shepard Stone, ›If RIAS cannot be defended against charges of pro-Communism, what or who can be?‹[85] The network of the ›Outpost‹ narrative’s boosters subsequently rushed to Ewing’s defense. Shepard Stone assured Ewing that former US High Commissioner ›McCloy and others have gone to work [for you]. For the sake of our country I hope that you will be spared coming back here to testify.‹[86] According to Stone, McCloy discreetly persuaded Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to stall Ewing’s summons.[87] Local Berliners also intervened on Ewing’s behalf. Ernst Reuter offered to write an open letter highlighting his anti-Communist credentials.[88] Moreover, RIAS senior journalists publicly threatened to quit if Ewing were to be subpoenaed.[89] The campaign to prevent Ewing from testifying demonstrates the political clout of the network of the ›Outpost‹ narrative’s boosters, as McCarthy never succeeded in bringing Ewing to testify on the Senate floor. Their clout derived from their association with a West Berlin that had become synonymous with ›Freedom from Communism‹ for the American public by 1954.

3. Conclusion

The conception of West Berlin as an ›Outpost of Freedom‹ drew from Berlin’s history, dating back to its explosive growth in the Wilhelmine era. Stressing Berlin’s past as a cosmopolitan city that was in many ways politically and culturally distinct from Germany at large allowed its boosters to counter competing, less flattering associations, such as Berlin’s role as the Nazi Reichshauptstadt. But uniquely to Berlin, the dominant narrative of postwar reconstruction appealed to the collective memories of both local Germans and American occupiers.

Reimagining a mountain of rubble as the new ›Outpost of Freedom‹ entailed considerable benefits for West Berliners, non-communist local politicians, and American occupation officials alike. For West Berliners, the role of ›heroic defenders of democracy‹ simultaneously offered moral rehabilitation, an outlet for continuing anti-Communist resentment, reorientation in a new political framework, and the opportunity to forget the legacy of the Nazi regime. This narrative construction gave politicians such as Social Democratic Governing Mayor Ernst Reuter an explanation for Berliners’ plight that won votes and considerable political concessions from their American occupiers, and earned SPD politicians belated vindication for their personal fight against the NSDAP. American officials reveled in the role of benevolent occupiers, as it offered affirmation at a critical juncture. Former inhabitants of the Reichshauptstadt yearning for American-style liberal democracy not only pointed to the political potency of their ideals, but also affirmed American Cold War foreign policy.

(Landesarchiv Berlin, Schütz, Gert, F Rep. 290 [06], No. 0037192)

Given these stakes, West Berlin politicians, local journalists, and American occupation officials quickly came together to promote this narrative. They could command considerable resources for the popularization of the ›Outpost of Freedom‹, such as the organization of the politically dominant SPD, supportive media coverage, exemplified by RIAS, and American investments in West Berlin’s viability. Popularizing the ›Outpost of Freedom‹ on such a large scale required immense coordination that proceeded quietly, but intensely. The surprisingly smooth cooperation between Germans and Americans was fostered by shared anti-totalitarian convictions. Both sides shared the experience of Nazism in the past, disdain for the Soviet policies in the present, and hopes for a liberal democratic Europe in the future. In addition, the personal experiences of many coordinating figures bridged cultural divides. Key personnel on the West Berlin side, such as Ernst Reuter and Hans Hirschfeld, had spent World War II in exile. Many Americans had personal experience with Europe, and with astonishing intensity. During their education at the Universities of Paris and Berlin, respectively, US City Commander Frank Howley and HICOG Public Affairs director Shepard Stone accumulated cultural capital upon which they relied in postwar Berlin.

Reconfiguration of established Berlin tropes, popularized and coordinated by powerful actors, proved instrumental for the success of the ›Outpost‹ narrative in postwar Berlin and beyond. The ›Outpost of Freedom‹ created an imagined community based on a shared memory that spanned the Atlantic. The durability and cohesion of the narrative are further metrics for its extraordinary success. Moreover, this ›special relationship‹ between West Berlin and the United States has never been a project of political elites alone, but was also part of the personal biographies of thousands of Berliners.

(Landesarchiv Berlin, Sass, Bert, F Rep. 290 [04], No. 0092949)

Some happily remember the good times they had at the various centers of the German Youth Activities or at the German-American Volksfest, while others point out the cultural importance of the many American-sponsored institutions like the Amerika-Haus, the Bücherbus, or the Freie Universität. During the more than four decades of the occupation, countless formal and informal encounters took place – at joint police patrols, at the numerous German-American clubs, or at the many GI bars that brought Rock’n’Roll, Hip Hop, and R’n’B to the walled-in city.[90] Some of these encounters had long-lasting consequences. From the 1960s to the 1990s, nearly every third groom in the southern district Zehlendorf was an American.[91]

Despite several massive but eventually temporary challenges between the late 1960s and early 1980s, the interpretation of the United States as a protecting power prevailed. This may sound astonishing, since images of demonstrations against the Vietnam War and riots on occasion of two visits by US President Ronald Reagan dominate German cultural memory. However, these images are only part of the picture.

(bpk/Alexander Enger)

At the same time, German students were reaching out to American GIs, whom they considered potential partners in their fight to end the war in Vietnam.[92] While public memory focuses on people who protested against the Cold War rhetoric of the Reagan administration, this obscures the fact that the same number of people were applauding Reagan’s words only a few streets away. In 1985, three-quarters of the Berliners did not want the Western allies to leave the city.[93] A survey conducted by the EMNID institute came to the surprising conclusion that ›the trust in the Western Power’s safety guarantees has never been that high before‹.[94] Although appreciation of the Allied military presence had decreased slightly during the following years, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 helped not only to re-establish the old Cold War narrative, but to append to it a happy ending.

To this day, West Berlin’s history has made the city of Berlin an eminent American lieu de mémoire. Among the throng of American visitors in June 2013 was President Barack Obama. Exclaiming that ›here […] Berliners carved out an island of democracy against the greatest of odds […] supported by an airlift of hope‹, Obama invoked the ›Outpost‹ narrative to campaign for his foreign policy vision of global ›peace with justice‹. In a wry understatement, Obama noted that he was ›not the first American President to come to this [Brandenburg] gate‹.[95] In the last half century, all but three sitting US Presidents visited Berlin. Each one sought to bolster the appeal of his foreign policy by framing it within the narrative of the ›Outpost of Freedom‹.

Notes:

[1] Concord at Berlin, in: New York Times, July 4, 1945, p. 12.

[2] Tania Long, This is Berlin – Without Hitler. An eyewitness account of life today, in: New York Times, July 22, 1945, p. 77.

[3] Journal entry, December 2, 1945, in: John J. Maginnis, Military Government Journal. Normandy to Berlin, ed. by Robert A. Hart, Amherst 1971, p. 319.

[4] Cf. for example: Klaus-Dietmar Henke, Der freundliche Feind: Amerikaner und Deutsche 1944/45, in: Heinrich Oberreuter/Jürgen Weber (eds), Freundliche Feinde? Die Alliierten und die Demokratiegründung in Deutschland, Munich 1996, pp. 41-50, especially pp. 49-50; David Clay Large, Berlin. Biographie einer Stadt, Munich 2002, p. 543; Jürgen Wenzel, Aus Feinden wurden Freunde. Die Amerikaner in Berlin 1945–1949, in: Michael Bienert/Uwe Schaper/Andrea Theissen (eds), Die Vier Mächte in Berlin. Beiträge zur Politik der Alliierten in der besetzten Stadt, Berlin 2007, pp. 69-79; Eckart Conze, Die Suche nach Sicherheit. Eine Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland von 1949 bis in die Gegenwart, Munich 2009, p. 40; Wilfried Rott, Die Insel. Eine Geschichte West-Berlins 1948–1990, Munich 2009, pp. 40-41; James J. Sheehan, Kontinent der Gewalt. Europas langer Weg zum Frieden, Munich 2008, p. 194.

[5] Based on Article 5 and 6 of the North Atlantic Treaty, the Allies would have been able to consider an attack against West Berlin as an attack against themselves and thereby against NATO, because their troops were stationed there. Cf. Udo Wetzlaugk, Berlin und die deutsche Frage, Sonderaufl. für die Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Berlin, Cologne 1985, pp. 79-83; The North Atlantic Treaty, April 4, 1949, URL: <http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm>.

[6] Cf. Sebastian Conrad, The Quest for the Lost Nation. Writing History in Germany and Japan in the American Century, Berkeley 1999, pp. 235-262.

[7] Rolf Lindner, Offenheit – Vielfalt – Gestalt. Die Stadt als kultureller Raum, in: Friedrich Jäger/Jörn Rüsen (eds), Handbuch der Kulturwissenschaften, Vol. 3: Themen und Tendenzen, Stuttgart 2004, pp. 385-398, here p. 392.

[8] Aleida Assmann, Erinnerungsräume. Formen und Wandlungen des kulturellen Gedächtnisses, Munich 1999, p. 299.

[9] Cf. Alexa Färber, Urbanes Imagineering in der postindustriellen Stadt: Zur Plausibilität Berlins als Ost-West-Drehscheibe, in: Thomas Biskup/Marc Schalenberg (eds), Selling Berlin. Imagebildung und Stadtmarketing von der preußischen Residenz bis zur Bundeshauptstadt, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 279-296; Martina Löw, Soziologie der Städte, Frankfurt a.M. 2008.

[10] Gerald D. Suttles, The Cumulative Texture of Local Urban Culture, in: American Journal of Sociology 90 (1984), pp. 283-304, here pp. 285, 288.

[11] Ibid., p. 293.

[12] Ibid., pp. 295, 298.

[13] Cf. Janet Ward, Post-Wall Berlin. Borders, Space and Identity, New York 2011, pp. 26-36.

[14] Walther Rathenau, Die schönste Stadt der Welt, in: id., Impressionen, Leipzig 1902, p. 144.

[15] Cf. Peter Fritzsche, Reading Berlin 1900, Cambridge 1998.

[16] Mark Twain, The Chicago of Europe. And Other Tales of Foreign Travel, ed. by Peter Kaminsky, New York 2009, pp. 191-192.

[17] Cf. Scott H. Krause, A Modern Reich? American Perceptions of Wilhelmine Germany, 1890–1914, in: Konrad H. Jarausch/Harald Wenzel/Karin Goihl (eds), Different Germans, Many Germanies. New Transatlantic Perspectives, New York 2016 (forthcoming).

[18] Cf. Daniel Kiecol, Selbstbild und Image zweier europäischer Metropolen. Paris und Berlin zwischen 1900 und 1930, Frankfurt a.M. 2001, pp. 256-262; Klaus R. Scherpe, Berlin als Ort der Moderne, in: Pandaemonium Germanicum 7 (2003), pp. 17-37.

[19] Cf. Daniel Kiecol, Berlin und sein Fremdenverkehr: Imageproduktion in den zwanziger Jahren, in: Biskup/Schalenberg, Selling Berlin (fn. 9), pp. 161-174; Friedrich Lenger, Metropolen der Moderne. Eine europäische Stadtgeschichte seit 1850, München 2013, S. 216.

[20] Der Fremde in Berlin, 1922, p. 3, cited in: Kiecol, Selbstbild und Image (fn. 18), p. 261.

[21] Letter Shepard Stone to Charlotte Stone, November 27, 1943, in: Dartmouth College, Rauner Special Collections Library (Dartmouth Special Collections), Shepard Stone Papers, ML-99, Series 2, WWII, 1941–1945, Box 3, Folder 64, Charlotte Stone: Letters from Shepard Stone, 1943.

[22] For the strong reactions to the sight of Berlin’s ruins, cf. Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, Gazing at Ruins: German Defeat as Visual Experience, in: Journal of Modern European History 9 (2011), pp. 328-350.

[23] Long, This is Berlin (fn. 2).

[24] John Thompson, Night life back in Berlin, but it clips you $150, in: Chicago Daily Tribune, December 16, 1946, p. 3.

[25] Gaststätten und Hotels, in: Der Abend, December 27, 1947.

[26] US Headquarters Berlin District, An Illustrated Introduction to the City of Berlin, Berlin 1947, p. 4.

[27] For more information on the history of Berlin during the Third Reich and the myth of a ›Red Berlin‹, see Oliver Reschke/Michael Wildt, Aufstieg der NSDAP in Berlin, in: Michael Wildt/Christoph Kreutzmüller (eds), Berlin 1933–1945. Stadt und Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus, Berlin 2013, pp. 19-32; Daniel Siemens, Prügelpropaganda. Die SA und der nationalsozialistische Mythos vom ›Kampf um Berlin‹, in: ibid., pp. 33-50.

[28] Jennifer V. Evans, Life Among the Ruins. Cityscape and Sexuality in Cold War Berlin, New York 2011, p. 152.

[29] For the long-lasting and sometimes very heated debates concerning Germany’s future, see Klaus-Dietmar Henke, Die amerikanische Besetzung Deutschlands, Munich 1995, 3rd ed. 2009.

[30] Briefing for General Taylor enclosed in letter Clark Denney to Fred Shaw, September 18, 1950, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), RG 466, Box 3, HICOG Berlin Element, Folder German-American relations, pp. 1-2.

[31] Command Report Berlin Military Post, 1951, NARA, RG 549, EUCOM General Staff, Berlin Military Post, Box 1617, p. 13.

[32] Office of the HICOG, Office Memorandum, Subject: Report on IB Pamphlet Operation for 1952, Supplement: Berlin’s Special Events, January 1, 1952, NARA, RG 466, HICOG Berlin Element, Public Affairs, Box 2.

[33] Cf. for example: Dominik Geppert, Symbolische Politik. Berliner Konjunkturen der Erinnerung an die Luftbrücke, in: Helmut Trotnow/Bernd von Kostka (eds), Die Berliner Luftbrücke. Ereignis und Erinnerung, Berlin 2010, pp. 136-147, here p. 137.

[34] Cf. Paul Steege, Totale Blockade, totale Luftbrücke? Die mythische Erfahrung der ersten Berlinkrise, Juni 1948 bis Mai 1949, in: Burghard Ciesla/Michael Lemke/Thomas Lindenberger (eds), Sterben für Berlin? Die Berliner Krisen 1948 : 1958, Berlin 2000, pp. 59-78.

[35] Lucius D. Clay, draft of a speech sent to EUCOM in August 1948, private archive of Bryan van Sweringen, Berlin.

[36] George H. Gallup, The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion 1935–1971, Vol. 1, New York 1972, p. 748.

[37] Office of the HICOG, Secret Policy Book, June 15, 1950, NARA, RG 59, Department of State (DoS), Legal Adviser German Affairs, Box 1, p. 3.

[38] Bange machen gilt nicht!, in: Der Abend, June 24, 1948. On the successful attempt by the city’s government to create a transatlantic network and to draw attention on the situation in Berlin, see David E. Barclay, Mythos, Symbol, Realpolitik. Ernst Reuter und die Blockade, in: Trotnow/von Kostka, Die Berliner Luftbrücke (fn. 33), pp. 149-157, here p. 150.

[39] Zwölf Stunden ohne Blockade, in: Telegraf am Abend, May 12, 1949, p. 1; Berlin verdient die Achtung der Welt, in: Telegraf, May 12, 1949, p. 1.

[40] Cf. Geppert, Symbolische Politik (fn. 33), p. 144.

[41] Briefing on Current Berlin Problems, May 2, 1950, Directors Building in Berlin, NARA, RG 466, HICOG Berlin Element, Public Affairs, Box 3.

[42] Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, in: Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1893, Washington 1894, pp. 199-227. Cf. concerning the scholarly relevance and the ongoing popularity of Turner’s assertion: Lacy K. Ford Jr., The Turner Thesis Revisited, in: Journal of the Early Republic 13 (1993), pp. 144-163, here p. 145; Patrick J. Denee, Cities of Man on a Hill, in: American Political Thought 1 (2012), pp. 29-52.

[43] ›No other piece of American historical writing so legitimated the American historical imagination, stimulated so thorough an inquiry, precipitated so furious a dispute over so long a period, and embedded itself so deeply into the American psyche.‹ Martin Ridge, The Significance of Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis, in: Montana. The Magazine of Western History 41 (1991), pp. 2-13, here p. 13.

[44] Cf. concerning Berlin as a ›frontier city‹: Ward, Post-Wall Berlin (fn. 13), pp. 26-36.

[45] NARA, The Big Picture: Berlin Duty (1963 or 1964), minute 18:55, URL: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMckfMFHMPQ>.

[46] Ernst Reuter, Rede auf der Protestkundgebung vor dem Reichstagsgebäude am 9. September 1948 gegen die Vertreibung der Stadtverordnetenversammlung aus dem Ostsektor, in: id., Schriften, Reden, ed. by Hans E. Hirschfeld and Hans Joachim Reichhardt, Vol. 3, West Berlin 1974, pp. 477-479.

[47] The Current State of West Berlin Morale, February 29, 1952, in: NARA, RG 306, Office of Research and Analysis, German Public Opinion, Box 2, pp. 1-4.

[48] Cf. Survey: Das Vertrauen zu den Schutzmächten, March 1966, in: Landesarchiv Berlin (LAB), B Rep. 002, Nr. 13320; David E. Barclay, On the Back Burner – Die USA und West-Berlin 1948–1994, in: Tilman Mayer (ed.), Deutschland aus internationaler Sicht, Berlin 2009, pp. 25-36, here p. 31.

[49] John F. Kennedy, Speech at the Rathaus Schöneberg, June 26, 1963, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, URL: <http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/oEX2uqSQGEGIdTYgd_JL_Q.aspx>.

[50] Richard Nixon, Remarks at the Siemens Factory, February 27, 1969, The American Presidency Project, URL: <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2427>.

[51] Jimmy Carter, Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany Remarks at a Wreathlaying Ceremony at the Airlift Memorial, July 15, 1978, The American Presidency Project, URL: <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=31086#axzz2hG1lpHwL>.

[52] John Winthrop, the second governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, frequently used the metaphor from the Sermon on the Mount to describe the Puritan’s mission. It is considered to be the origin of the idea of American exceptionalism. Carter’s speechwriter suggested mentioning Winthrop, but Carter removed the reference and insisted on quoting the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5:14). Jim Fallows, Remarks at Airlift Memorial, Berlin, July 10, 1978, in: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, Susan Clough Files, Presidential Travel 4/14/77 – 10/13/80 through Telephone, Memoranda and Movement Logs 8/12/80 – 9/28/80, Box 43, Folder: Speeches For Trip to Germany 7/78, p. 6.

[53] Ronald Reagan, Speech at the Brandenburg Gate, June 12, 1987, URL: <http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/ronaldreaganbrandenburggate.htm>.

[54] Cf. Jay Parini, The American Mythos, in: Daedalus 141 (2012), pp. 52-60; Richard T. Hughes, Myths America Lives By, Urbana 2003.

[55] Hilde Eliassen Restad, Old Paradigms in History – Die Hard in Political Science: US Foreign Policy and American Exceptionalism, in: American Political Thought 1 (2012), pp. 53-76.

[56] Cf. concerning a similar development in West Germany: Petra Goedde, GIs and Germans. Culture, Gender and Foreign Relations, 1945–1949, New Haven 2003, p. 124.

[57] Speech given by Mr. Downs: Briefing on Current Berlin Problems, May 2, 1950, Directors Building in Berlin, NARA, RG 466, HICOG Berlin Element, Public Affairs, Box 3, pp. 11-12.

[58] Untitled paper, July 14, 1950, NARA, RG 466, HICOG, Berlin Element, Public Affairs, Box 3.

[59] Peter Bender, Sterben für Berlin, in: Ciesla/Lemke/Lindenberger, Sterben für Berlin? (fn. 34), pp. 11-24, here p. 20.

[60] Cf. Harold Hurwitz, Die Anfänge des Widerstands, 2 vols, Cologne 1990.

[61] US Liaison office to the West Berlin government documents the intensity of the cooperation, cf. Memo ›Activities of the Liaison Office with the Oberburgermeister from 1945–1949‹, October 15, 1949, in: LAB, E Rep. 300-62, 16, Nachlass Karl F. Mautner, Berichte über das Verhältnis zwischen Amerikanern und Berlinern in Berlin.

[62] Cf. for Reuter’s and Clay’s personal relationship: Rott, Die Insel (fn. 4), pp. 27-44.

[63] For Hirschfeld’s biography, cf. Scott H. Krause, Hans E. Hirschfeld, 1894–1971. West Berlin’s Public Relations Manager and Informal Representative to the American Government, in: Transatlantic Perspectives, July 2013, URL: <http://www.transatlanticperspectives.org/entry.php?rec=146>.

[64] For the organization and reception of Ernst Reuter’s visits to the United States, cf. Björn Grötzner, Outpost of Freedom. Ernst Reuters Amerikareisen, 1949–1953, Berlin 2014.

[65] Invitation letter to Hans Hirschfeld, August 8, 1949, in: LAB, E Rep 200-21, 172, Nachlass Ernst Reuter, Allgemeiner Briefwechsel, Band 1949.

[66] Letter of Hans Hirschfeld to Charlotte Thormann, May 17, 1950, in: LAB, E Rep 200-18, 34/3, Nachlass Hans Hirschfeld, Korrespondenz.

[67] Memo on Survey of Foreign Experts, Confidential, May 1, 1945, in: LAB, E Rep 200-18, 4, Nachlass Hans Hirschfeld, Arbeitsunterlagen während der Emigration; Memo Charlotte Stone to John C Hughes, May 15, 1945, in: Dartmouth Special Collections, Shepard Stone Papers, ML-99, Series 2, WWII, 1941–1945, Box 3, Folder 72, Charlotte Stone: OSS correspondence, 1941, 1944–1945, undated.

[68] For this network’s agenda in West German domestic politics, cf. Scott H. Krause, Neue Westpolitik: The Clandestine Campaign to Westernize the SPD in Cold War Berlin, 1948–1958, in: Central European History 48 (2015), pp. 79-99 (forthcoming).

[69] Top Secret Subject Files, 1953–1958, Bonn Embassy, Germany, NARA, RG 84, Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Lot No. 61, F23, Box 1.

[70] According to state of the art American polling. Cf. Information S.D.H. Research Analysis Branch, Report No 4, Series No 2: RIAS and its Listeners in Western Berlin, February 8, 1950, p. 2, in: Harold Hurwitz, Die West-Berliner Öffentlichkeit vom Kalten Krieg bis zur Entspannungspolitik, Forschungsarchiv, URL: <http://www.gesis.org/unser-angebot/daten-analysieren/umfragedaten/uebersichten/hurwitz-berlin-nach-1945/>.

[71] Memorandum ›NZ and hereafter‹, December 15, 1954, in: LAB, E Rep 300-62, 54, Nachlass Karl F. Mautner, Berliner Pressewesen.

[72] Loudspeakers mounted on US Army trucks carried the RIAS program to West Berliners whose electricity had been mostly cut. In addition, the demolition of the Communist dominated Berliner Rundfunk’s transmitter in the French sector impeded reception of RIAS’s main competitor. Cf. Herbert Kundler/Jutta U. Kroening, RIAS Berlin: Eine Radio-Station in einer geteilten Stadt. Programme und Menschen – Texte, Bilder, Dokumente, 2nd ed. Berlin 2002, p. 103.

[73] Cf. Petra Galle, RIAS Berlin und Berliner Rundfunk 1945–1949. Die Entwicklung ihrer Profile in Programm, Personal und Organisation vor dem Hintergrund des Kalten Krieges, Münster 2003.

[74] Nicolas J. Schlosser, Creating an ›Atmosphere of Objectivity‹. Radio in the American Sector, Objectivity and the United States’ Propaganda Campaign against the German Democratic Republic, 1945–1961, in: German History 29 (2011), pp. 601-627, here pp. 610-611.

[75] Kundler/Kroening, RIAS Berlin (fn. 72), pp. 407-408.

[76] Letter of Fred G. Taylor to Ernst Reuter, October 1, 1949, in: LAB, B Rep 002, 8640, Der Regierende Bürgermeister von Berlin – Senatskanzlei – RIAS Berlin, 1949–1957.

[77] Letter of Fred G. Taylor to Ernst Reuter, May 10, 1950, in: LAB, B Rep 002, 8640, Der Regierende Bürgermeister von Berlin – Senatskanzlei – RIAS Berlin, 1949–1957.

[78] Underlining original, cf. Letter of Hans E. Hirschfeld to Fred G. Taylor, December 16, 1953, in: LAB, E Rep. 200-18, 43/4, Nachlass Hans Hirschfeld, Korrespondenz.

[79] Memorandum Abteilung Massenorgane (A), Bericht über den außerordentlichen Landesparteitag der SPD, June 22, 1957, in: Bundesarchiv Berlin (BAB), SAPMO DY/30/IV 2/10.02/169, Zentrales Parteiarchiv der SED, ZK, Westabteilung, 207.

[80] 2 Newspaper Men Balk at Red Inquiry, in: New York Times, July 14, 1955, p. 1.

[81]Letter Charles S. Lewis to Hans Hirschfeld, July 30, 1955, in: LAB, E Rep. 200-18, 39/6, Nachlass Hans Hirschfeld, Korrespondenz.

[82] Aides of McCarthy Open Bonn Inquiry, in: New York Times, April 7, 1953, p. 14.

[83] Won’t Comment on Statement, in: New York Times, July 22, 1953, p. 9.

[84] Agit-Prop-Broschüre ›Ein Mann kam nach Berlin‹, 1957, in: BStU, MfS, ZAIG, Nr. 356, pp. 96-118.

[85] Letter Gordon Ewing to Shepard Stone, July 20, 1953, in: Dartmouth Special Collections, Shepard Stone Papers, ML-99, Series 4: High Commission For Germany (HICOG), 1949–1953, Box 13, Folder 6, Correspondence, 1953–1954.

[86] Letter Shepard Stone to Gordon Ewing, July 14, 1953, in: George C. Marshall Research Library, Gordon Ewing Collection, Box 1, Folder 3, RIAS Gordon Ewing Letters.

[87] Letter Shepard Stone to Gordon Ewing, July 21, 1953.

[88] Letter Gordon Ewing to Shepard Stone, July 20, 1953.

[89] Kundler/Kroening, RIAS Berlin (fn. 72), pp. 189-198; Germans Threaten To Quit RIAS Staff, in: New York Times, June 22, 1953, p. 9; U.S. Official Backs RIAS, in: New York Times, June 27, 1953, p. 3; McCarthy Firm on RIAS, in: New York Times, June 28, 1953, p. 18.

[90] Cf. Bodo Mrozek’s contribution in this issue.

[91] Cf. Tamara Domentat, Foreign Affairs. Deutsch-amerikanische Liebesgeschichten zwischen Fraternisierungsverbot und Hochzeitsstreß, in: id. (ed.), Coca-Cola, Jazz und AFN. Berlin und die Amerikaner, Berlin 1995, pp. 153-166, here p. 161.

[92] Cf. Martin Klimke, The Other Alliance. Student Protests in West Germany and the United States in the Global Sixties, Princeton 2010; Martin Klimke/Maria Höhn, A Breath of Freedom. The Civil Rights Struggle, African-American GIs, and Germany, Basingstoke 2010.

[93] According to an opinion poll conducted by the SFB (Sender Freies Berlin), 85% of the Berliners agreed that Berlin has benefitted from the presence of the Allied troops. 80% were convinced that the city would not have been able to survive without the Allied safety guarantees, 78% wanted them to stay. Vermerk, Betreff: SFB-Meinungsumfrage zum Thema ›Alliierte in Berlin‹, October 29, 1985, LAB, B Rep. 002, Nr. 24624.

[94] Survey ›Politik-Trends: Zur politischen Lage in West-Berlin‹, September 1985, LAB, B Rep. 002, Nr. 24624.

[95] ›We have history to make‹, in: Spiegel Online, June 19, 2013, URL: <http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/obamas-rede-in-berlin-am-19-juni-2013-im-wortlaut-englisch-a-906741.html>.

![›For sale: slightly used airline, one well equipped airfield, present owners going out of business.‹ Group Captain Brian C. Yarde (Commanding Officer RAF), Col. John E. Barr (Tempelhof Commander), Admiral John Wilkes, and Governing Mayor Ernst Reuter celebrating the end of the Berlin Blockade in May 1949. While Americans and Germans were relieved, the historical significance of this crisis for the transatlantic partnership remains under discussion to this day. (Landesarchiv Berlin, Photo: N.N., F Rep. 290 [02], No. 0255844)](/sites/default/files/medien/cumulus/2014-2/Eisenhuth_Krause/resized/2125.jpg)

![Berliners listening to a speech given by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson in front of the city hall on August 19, 1961. A few days before, the building of the Berlin Wall had been started. (Landesarchiv Berlin, Willa, Johann, F Rep. 290 [02], No. 0076200)](/sites/default/files/medien/cumulus/2014-2/Eisenhuth_Krause/resized/2123.jpg)

![Among the many charity projects by the US Army in West Berlin were also annual Christmas parties for orphans and children from poor families. The photo was taken at the McNair Barracks (Lichterfelde) in 1954. ( Landesarchiv Berlin, Schütz, Gert, F Rep. 290 [06], No. 0037192)](/sites/default/files/medien/cumulus/2014-2/Eisenhuth_Krause/resized/2126.jpg)

![When President Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, West Berliners were devastated. More than 130,000 signed the condolences books that were placed at the US headquarter (Clayallee, Zehlendorf – this photo) and the city hall. People put candles in their windows, and governing mayor Willy Brandt bemoaned the loss of the city’s ›best friend‹. (Landesarchiv Berlin, Sass, Bert, F Rep. 290 [04], No. 0092949)](/sites/default/files/medien/cumulus/2014-2/Eisenhuth_Krause/resized/2128.jpg)