My Road to Berlin, or Mein Weg nach Berlin, presents a Willy Brandt that confounds a present-day reader’s expectations. While the 1960 autobiography of the then-mayor of West Berlin links his career with the familiar story of democracy’s development in Germany, this work nevertheless retains an unexpected edge. In one surprising scene, the mayor denounces his East Berlin SED counterparts as a ›Communist foreign legion‹ whom ›the citizens of my city had decisively defeated‹ during the Second Berlin Crisis of 1958 (p. 17). In the book, Brandt comes off as a Cold Warrior of steely determination rather than a Brückenbauer bridging ideological divides. Far from being out of character, however, My Road to Berlin captures Brandt at a pivotal moment in his career, when he sought to offer himself to both West German voters and a global public as a viable alternative to Konrad Adenauer. Moreover, rallying Berliners against the East German regime of Walter Ulbricht shielded Brandt from conservative accusations that the Social Democrats were soft on Communism. A skeptical electorate needed evidence of Brandt’s anti-Communist credentials before he could rise to a position from which to initiate new strategies. Brandt therefore arranged the geographically distinct parts of his biography under the rubric of ›freedom‹, presenting a combative public persona that his transformative chancellorship of the Federal Republic (1969–1974) later supplanted. Brandt’s Neue Ostpolitik as chancellor, which entailed reaching across the Iron Curtain and seeking détente, and which earned him a 1970 Nobel Peace Prize, effectively marginalized the trials he faced during his two decades in Berlin, from 1946–1966.

Brandt’s iconic stature stands in stark contrast to the suspicions that the politician faced during his postwar career. Accusations of disloyalty based on his wartime exile in Scandinavia hounded him since his return to Germany in 1946. As early as February 1948, nominal comrades such as the Berlin SPD Chairman Franz Neumann contacted Social Democrats in Sweden about Brandt’s conduct in exile.[1] Over a decade later, Adenauer exploited these suspicions during the 1961 Bundestag election campaign by disparaging his rival as ›Brandt alias Frahm‹, taking aim both at his illegitimate birth and the adoption of his nom de guerre as his legal name in postwar politics.[2] These accusations peaked when Minister of Defense Franz Josef Strauß of the CSU questioned Brandt’s loyalty to Germany, noting that Brandt had spent the Nazi era ›outside‹ (draußen), adding smugly: ›We know what we did here on the inside.‹[3]

Given these stakes, Brandt’s biography turned into a political battleground. Picking up on Strauß’s phrase, Brandt responded to these insinuations in book form in 1966. The new foreign minister’s collection of his exile-era writings, Draußen, coincided with his move to Bonn and intended to highlight his preoccupation with bringing democracy to Germany.[4] Moreover, Brandt offered no less than four book-length texts to interpret his ›atypical life’s journey‹.[5] His two political memoirs in particular, the first published shortly after the controversial end of his chancellorship and the second only weeks before the Berlin Wall’s collapse, have formed an indispensable source for Brandt’s biographers.[6] Links und frei. Mein Weg 1930–1950, published in 1982, concentrated on the author’s formative years in Weimar-era Lübeck, 1930s Norway, and wartime Sweden. Brandt presented a coming-of-age narrative in which a revolutionary socialist develops into a conciliatory Social Democrat at a time during which he reached out to a post-1968 generation that questioned the SPD’s passion for Marxism. Links und frei has met an enduring public interest, having recently been reissued.[7] The success of Brandt’s most personal autobiographic writing points to his sweeping victory in the wars over the memory of exile. The German public today reveres Brandt because of his past as an anti-fascist activist.

My Road to Berlin was conceived as ammunition in this battle. It reinterpreted Brandt’s biography, ruptured by twice fleeing the Nazis, as the fight for freedom. This choice resonated among contemporary readers as the battle cry of the Western side in the Cold War. Moreover, it effectively repurposed anti-fascist activism as anti-totalitarian activism. This semantic tweaking had two implications. First, it helped Brandt deemphasize his temporary break with the SPD for the fringe SAP, the Socialist Workers’ Party that advocated unity between Social Democrats and Communists. Second, this interpretation gave anti-fascist émigrés renewed relevance as dedicated and prescient spirits. Not surprisingly, it met enthusiastic backing by former émigrés, who coordinated their messaging to a surprising degree.

The publication of an autobiography stemmed from a transatlantic public relations campaign centered on Berlin that had been underway for over a decade. Hope of shaping postwar Germany attracted remigrés to the ruins of the Reichshauptstadt, most notoriously in the guise of the Gruppe Ulbricht.[8] On the other side of the quickly entrenched Cold War demarcation line, Social Democratic Mayor-Elect Ernst Reuter gathered fellow remigrés such as Berlin’s Marshall Plan coordinator Paul Hertz and PR director Hans Hirschfeld to promote West Berlin’s makeshift polity as the ›Outpost of Freedom‹. During the 1948/49 Berlin Airlift, this network comprised of many former exiles boldly reconceived the rubble of Hitler’s capital as the embodiment of democracy. This narrative belatedly vindicated the remigrés’ own anti-fascist struggles, gave Berliners an orientation toward democratic reconstruction, and provided successive West Berlin administrations a case that resonated emotionally with American occupiers. This network coordinated an elaborate, decades-long PR campaign to reach these audiences, inaugurating as physical manifestations of ›freedom‹ the Freedom Bell, Radio Free Berlin, and the Free University, among other things.[9]

Brandt’s career in postwar politics advanced through his membership in this circle. Brandt developed a close relationship with Reuter, with the shared experience of exile shaping the outlook of both men. For instance, the remigrés called for full West German integration into the western alliance, placing them at odds with national SPD chairman Kurt Schumacher and Berlin SPD chairman Neumann. While this Neue Westpolitik championed by West Berlin’s Schöneberg City Hall anticipated the position adopted by the party in its landmark 1959 Godesberg Program, the resulting feud divided the Berlin SPD for nearly a decade. In this confrontation over control of West Berlin’s dominant party, Brandt emerged as a staunch Reuter loyalist, first as a journalist, then as a member of the Abgeordnetenhaus (city parliament). Brandt’s affiliation with the remigrés’ network and their political priorities helped him forge excellent connections to like-minded officials within the American occupation apparatus, HICOG. Most notably, Brandt once processed 200,000 DM in clandestine American donations on Reuter’s behalf. In 1957, Brandt was elected mayor of West Berlin as Reuter’s political heir. The network quickly organized a high-level tour of the United States, bringing the newly minted mayor to lecterns at Harvard University, meetings with US Senators, and millions of American living rooms via CBS’ ›Face the Nation‹. Friendly radio broadcasts on RIAS and rolling coverage in the Bild-Zeitung during the trip helped to underscore Brandt’s association with youthful dynamism and cosmopolitanism.[10] This public image befitted his agenda of expanding the working-class SPD into a center-left big-tent party that shattered the party’s demographic ceiling.

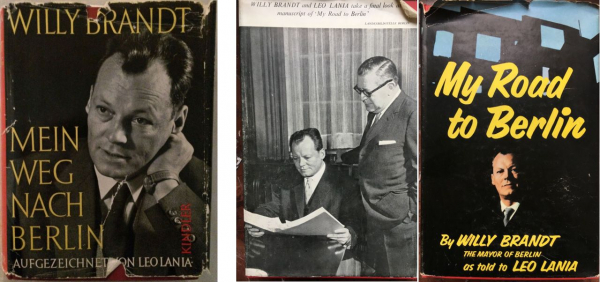

Authoring an autobiography of an exceptional past offered the opportunity to sculpt a winning public persona necessary to realize these lofty ambitions. Curiously, My Road to Berlin was published simultaneously in the United States and the Federal Republic, with other editions across the globe in short succession.[11] This unusual step exemplifies the importance Brandt and his support network placed on the American public in their transnational campaign to popularize West Berlin as the laboratory of an anti-Communist, pro-Western Left. Consequently, Brandt relied on a New York-based, German-speaking émigré to aid in writing the manuscript. While the division of labor between both writers remains murky, Brandt’s co-author was well-known in German-speaking exile circles. Leo Lania (1896–1961), born Lazar Herman, had been a frequent contributor to the Weltbühne, the eminent pro-democracy Weimar-era magazine, and he had introduced himself to an American audience by publishing a book on his own dramatic flight from Nazi-occupied Europe in 1941.[12] The transatlantic tandem of Brandt and Lania shared the perspective of émigrés as crucial cultural translators.

In My Road to Berlin, Brandt and Lania constructed a continuous biography under the banner of ›freedom‹. After surveying Brandt’s upbringing in Lübeck and his extensive travels and travails as an activist against Nazism, his initially tentative return to Germany in October 1945 formed the turning point of the narrative, neatly at its halfway point (p. 152). Brandt and Lania portrayed the Airlift in response to the Soviet blockade of Berlin’s Western sectors as the emotional peak. The authors particularly highlighted Reuter’s leadership in galvanizing Berliners’ resistance – and Brandt’s close association to this icon of anti-Communist resistance both in Germany and the United States.[13] Explaining the Airlift’s inception, Brandt recalls a meeting between Reuter and Lucius D. Clay, in which the West Berlin mayor encouraged the American military governor: ›Do what you are able to do; […] Berlin will make all necessary sacrifices and offer resistance – come what may.‹ (pp. 193-194) Regardless of the veracity of this surprising reversal of authority between occupier and occupied, this meeting of two ›great men‹ has been portrayed repeatedly as the beginning of German-American bonding in the city since Brandt.[14] Somewhat surprisingly for a text tailored to audience expectations, both the American and German versions follow the same chapter outline, while the texts mirror each other for most of their lengths. Minor exceptions were made for the readership in the Federal Republic in the depiction of Brandt’s political activities there. The American edition summarizes Brandt’s assessment of German reunification’s prospects (pp. 227-229), while its German-language counterpart documents his numerous speeches in the Bundestag.[15]

The authors creatively employed narrative techniques to smooth over potential ruptures in Brandt’s life, particularly during the first half of the book, which covers the period before his arrival in Berlin. For instance, Brandt referred to himself in the third person while describing his fatherless childhood, confiding to the reader that ›It is hard for me to believe that the boy Herbert Frahm was – I, myself‹ (p. 34). Brandt and Lania instead underscored the impact of Julius Leber’s tutelage for the young protagonist’s identity. The later Social Democratic resistance hero had ›always defended our right to express our own opinions freely and openly‹, despite their growing disagreements over the party’s reaction to Nazism. After joining the SAP in hope of building an anti-fascist Popular Front, Brandt lamented that he would only understand Leber’s skepticism of the Communists ›much later‹ (pp. 43-45). Leber’s defiance of the Nazis hence formed the dramatic climax of the Lübeck years (p. 57): ›The first of February [1933], two days after Hitler had been appointed Chancellor, Julius Leber was arrested‹, he wrote, ›then on the nineteenth of February, Lübeck saw one of the most powerful demonstrations in the history of the city. Fifteen thousand people gathered on the Burgfeld. The threats of the new rulers could not frighten them, the icy cold could not scare them away. [...] As [Leber] appeared on the platform with a bandaged head, unbroken, unbent, he shouted only a single word: »Freedom!« [...] Actually this was the last free demonstration in Lübeck. It was also the last time I saw Leber.‹ Brandt cited Leber as an inspiration to continue the struggle against the incipient Nazi regime, even if it required moving into exile. Consequently, Brandt portrayed his journey to Norway as a ›flight to freedom‹, despite the persecution and obstacles in his way (pp. 61-63).

The ›biography of continuity‹ genre helped Brandt gloss over possible contradictions in his life with its claim of fighting for freedom. For instance, he grouped his European travels for the Popular Front cause of the SAP under the chapter heading ›With the Underground in Berlin‹. While Brandt and Lania provided a gripping account of the capital’s Nazification during Brandt’s weeks in Hitler’s Berlin while undercover, this choice helped to deemphasize his five months in Spain in 1938. While Brandt continually maintained that he covered the Spanish Republic’s fight for survival as a journalist, political enemies such as Franz Neumann had insinuated that the émigré had taken up arms in a Communist International Brigade.[16] Instead of revisiting this controversy, Brandt highlighted his witnessing of the brutal silencing of the unorthodox Marxist POUM by Communists beholden to Moscow (pp. 85-91). More than twenty years later, Brandt presented reinforced skepticism toward Stalinism as his main takeaway.

The depiction of Brandt’s choice to return to Germany has ranked among the most prominent examples of a constructed continuity. Brandt and Lania vividly described the dizzying impressions upon first returning to an alienating country of birth and assessing the scale of destruction, but also the incongruity between Nazi ›extermination camps and the mass executions‹ and Brandt’s own German comrades’ purported unawareness of these events. Brandt confided that the offer to enter the Norwegian diplomatic service enticed him. His subsequent return in the uniform of a victorious power had enraged his German critics. Instead of marginalizing this episode, Brandt portrayed his move as a decision for Berlin (pp. 152-157, 164-165), a city in which Social Democrats sought to reconstruct a progressive Germany against Communist encroachment: ›Berlin – this decided the issue. Without hesitation I accepted the offer.‹ Yet the archival record suggests that Brandt kept his options open longer, using his post as press attaché in Berlin to ask Gunnar Myrdal about a position at the nascent United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE).[17]

Brandt and Lania turned the nativist argument on its head by highlighting Brandt’s cosmopolitanism as an asset. Consequently, but rather surprisingly, My Road to Berlin’s narrative begins in Lower Manhattan’s canyons of steel (p. 12): ›It was noon, February 10, 1959, slowly I drove along Broadway toward City Hall. I stood in the open car. [...] The applause of the crowd was like the surf of the ocean. Some shouts rose above the noise: »Hi, Willy!« »Good luck, Willy!«‹ By beginning with the iconic ticker-tape parade he received during his 1959 New York visit in the wake of the Second Berlin Crisis, Brandt and Lania presented the politician both as the personification of the international recognition that West German voters craved, as well as a warrior for American values receiving a recognition befitting the nation’s heroes.

Upon meeting a German-Jewish émigré in the crowd, Brandt explicitly drew a connection between the flight of persecuted émigrés in the Nazi era and the plight of West Berliners in the Cold War (p. 12): ›Once more I glanced at the man on the steps of Trinity Church. He did not look at all »American«; from his looks and attire one might have taken him for a European, perhaps an emigrant – he might have also been Jewish. How many among these men and women [...] had come to America but a few years ago, victims of Hitler’s madness, Jews and Christians alike? For thousands of them Germany had once been their home – later it became their hell. Now Broadway was their special domain.‹

Highlighting the hardships that émigrés had suffered and the contributions they made, Brandt portrayed this group – and by extension himself – as redeeming more benign German traditions that the Nazis had sought to destroy. In the next sentence, Brandt cited the plight of these émigrés as inspiration for the present in an inferred anti-totalitarian continuity (pp. 12-13): ›This ticker-tape parade [...] was an impulsive demonstration by which the people of this unique city [...] wanted to show their sympathy with the men and women of Berlin – with the Berlin which although conquered by the brown dictatorship had never been converted to the new creed, had to pay the heaviest penalty for the crimes of the Nazis, and which now, still bleeding from many wounds, was holding the front of freedom and human dignity against the red dictatorship. [...] Because they had not forgotten the past, could never forget it – these New Yorkers and my Berliners had the same claim on the future.‹ Hence Brandt cast the émigrés as crucial cultural links for Berliners successfully resisting dictatorial ambitions past and present.

Rereading political autobiographies can shed light on the political culture of the era, rather than resurrect the history of ›great men‹. Hence My Road to Berlin is most revealing not as a source, but if interpreted as a political gambit. Contextualizing the text both within the bibliography on Brandt and the constraints that the politician operated within underscores the significance of postwar Berlin for Brandt’s career. A widening chasm across the postwar left erupted from the city’s combative politics, which demanded a choice from exiled anti-fascists with increasing urgency. Most importantly, this unique urban space offered remigrés particular opportunities. Mayor Brandt could reinterpret his exile past, offering a post-Nazi electorate the kind of internationalism it craved through friendly news coverage, high-profile travel itineraries, and autobiographical works. My Road to Berlin offers the reader a carefully composed, patched-up biography of continuity, a narrative of a heroic past retrofitted to the exigencies of the Cold War. By presenting wartime anti-fascism that set him apart from most of the electorate as the anti-totalitarianism that his voters desired, Brandt made a shrewd political move. Yet the book’s most fascinating portions remain the subtleties underneath the streamlined narrative, following the authors’ delicate maneuvering between political constraints that at points demanded disavowing a constituent part of Brandt’s political past and obliquely advocating for émigrés’ recognition as indispensable cultural translators.

[1] Cf. Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep 300-90, 555, Nachlass Franz Neumann, Material von und zu Willy Brandt, Korrespondenz.

[2] Peter Merseburger, Willy Brandt, 1913–1992. Visionär und Realist, Stuttgart 2002, pp. 408-414.

[3] Moritz Pfeil [Rudolf Augstein], Unbewältigte Gegenwart, in: Spiegel, 3 August 1961, p. 28.

[4] Willy Brandt, Draußen. Schriften während der Emigration, ed. by Günter Struve, Munich 1966.

[5] Willy Brandt, Mein Weg nach Berlin, Munich 1960; Willy Brandt, Begegnungen und Einsichten. Die Jahre 1960–1975, Hamburg 1976; Willy Brandt, Links und frei. Mein Weg 1930–1950, Hamburg 1982; Willy Brandt, Erinnerungen, Frankfurt a.M. 1989.

[6] Gregor Schöllgen, Willy Brandt. Die Biographie, Berlin 2001; Merseburger, Willy Brandt (fn. 2); Helga Grebing, Willy Brandt. Der andere Deutsche, Paderborn 2008; Einhart O. Lorenz, Willy Brandt. Deutscher – Europäer – Weltbürger, Stuttgart 2012; Bernd Faulenbach, Willy Brandt, Munich 2013; Hélène Miard-Delacroix, Willy Brandt, Paris 2013; Hans-Joachim Noack, Willy Brandt. Ein Leben, ein Jahrhundert, Berlin 2013.

[7] Willy Brandt, Links und frei. Mein Weg 1930–1950, Hamburg 2012.

[8] Siegfried Heimann, Politische Remigranten in Berlin, in: Claus-Dieter Krohn/Patrik von zur Mühlen (eds), Rückkehr und Aufbau nach 1945. Deutsche Remigranten im öffentlichen Leben Nachkriegsdeutschlands, Marburg 1997, pp. 189-210.

[9] Stefanie Eisenhuth/Scott H. Krause, Inventing the ›Outpost of Freedom‹. Transatlantic Narratives and Actors Crafting West Berlin’s Postwar Political Culture, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 10 (2014), pp. 188-211.

[10] Scott H. Krause, Neue Westpolitik: The Clandestine Campaign to Westernize the SPD in Cold War Berlin, 1948–1958, in: Central European History 48 (2015), pp. 79-99. For Brandt’s savvy adaptation of American PR strategies tailored to broadcasting media, see Daniela Münkel, Als »deutscher Kennedy« zum Sieg? Willy Brandt, die USA und die Medien, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 1 (2004), pp. 172-194.

[11] E.g. translations in French, Spanish, Japanese, Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, and Finnish.

[12] Leo Lania/Ralph Manheim, The Darkest Hour. Adventures and Escapes, Boston 1941.

[13] For Reuter’s contemporary popularity on both sides of the Atlantic, cf. David E. Barclay, Schaut auf diese Stadt. Der unbekannte Ernst Reuter, Berlin 2000; Björn Grötzner, Outpost of Freedom. Ernst Reuters Amerikareisen 1949 bis 1953, Berlin 2014.

[14] Most recently, Wilfried Rott, Die Insel. Eine Geschichte West-Berlins 1948–1990, Munich 2009, pp. 36-37.

[15] Cf. Brandt, Mein Weg nach Berlin, pp. 285-295.

[16] Merseburger, Willy Brandt (fn. 2), p. 341; Rott, Insel (fn. 14), p. 131.

[17] Willy Brandt, brev till Gunnar Myrdal, 19 June 1947, Gunnar och Alva Myrdals arkiv, Gunnar Myrdal brevsamling 1947–1957, volym 3.2.2:2, Arbetarrörelsens arkiv och bibliotek, Stockholm. For the candid correspondence between Brandt and Myrdal, cf. Scott H. Krause/Daniel Stinsky, For Europe, Democracy and Peace: Social Democratic Blueprints for Postwar Europe in Willy Brandt and Gunnar Myrdal’s Correspondence, 1947, in: Themenportal Europäische Geschichte, 2015.

Further Reading:

Special Issue ›West Berlin‹ (2/2014)

Section ›Rereadings‹