[I would like to thank Jasmine Chorley-Schulz and Miko Zeldes-Roth as well as the editors of this special issue for their invaluable feedback.]

It is not for nothing that the methodology of thinking with political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), or against or beyond her, is a favorite of scholars who engage (with) her work.1 Her oeuvre remains a land of contradictions, provocatively and productively so – defying attempts to categorize, encase, fixate, not least because of her prolificity in multiple languages and her discrete phases of intellectual inquiry. Controversies consequently punctuated her life.

Few of Arendt’s declarations have had as enduringly a controversial legacy as the one she gave in a 1964 West German television interview, proclaiming uncompromised loyalty to her first language – German – despite Hitler. When asked ›was ist nach Ihrem Eindruck geblieben, und was ist unrettbar verloren‹ [what, according to you, remains, and what is irretrievably lost] of pre-Hitler Europe, she replied: ›Was bleibt? Es bleibt die Muttersprache.‹ [What remains? The mother tongue remains.]2 Amidst controversies over her report on the Eichmann trial,3 her enduring affinity for German might seem rather harmless today and unrelated to her most famous writings. But, predominantly in the United States, it was grist for the mills of those who misconstrued her report as downplaying the role of Nazi perpetrators, blaming Jewish victims, and biasedly anti-Ostjuden.4 Old-world discord between German-Jewish universalism and an ethnonational self-understanding common among Eastern European Jews was rehashed and projected onto Arendt’s language choices (German versus Yiddish) – so many people read her as elitist and privileging the language of the perpetrators.5 These intertwined controversies encapsulate the naturalization of monolingualism and identity politics, related to the concurrent sacralization of the Holocaust and its survivors, that emerged on the New Left and (religious) right in the late 1960s.6

In this paper, I, too, want to think with, against, and beyond Arendt about her language politics with an eye towards their anti-racist potentials.7 I will argue that there is a specific Arendtian approach to language that works against the modern tendency that conceives of languages as property of national identities and independent (sovereign, even) from other languages.8 Languages – and their speakers – in fact live in and through other languages, resonating from deep within, and constantly cross-fertilize; they (we) evolve together. I will develop this argument by way of Arendt’s Yiddish practices and writings in the 1930s and 1940s – right before she became, as Samuel Moyn recently stated, an ›imperfect‹ fellow traveler of Cold War liberals.9 In 1947 and 1948, in the heat of the incipient Cold War, Arendt departed from her previous thinking, including in Yiddish, most importantly by breathing life into the originally center-right totalitarian paradigm (equalizing the Soviet Union with Nazism) and a commitment to defending notions of Western civilizational supremacy.10 Although none of these Yiddish texts are prominent in her vast corpus, they not only tell us something about Arendt’s politics – if only for a time – towards languages, but are also instructive about the modern relationship between language, ethnonationalism and racism, and how to resist the same.

The aim of this paper is to explore what I call a ›Taytsh move‹ in Arendt’s language practices and politics. I follow the recent ›Taytsh turn‹ in Yiddish Studies ›to enact multidirectional readings of Yiddish cultural objects‹, ushered in and most powerfully formulated by Saul Zaritt.11 Simply put, Taytsh was and remains an older, alternative name for the Yiddish language: Taytsh and Yiddish, that is to say, are two names for one Jewish vernacular that productively draws on and brings into mutual relation Germanic, Hebrew, Slavic, and other linguistic elements. It has its beginnings presumably sometime in the Middle High German-speaking Rhineland roughly a millennium ago and evolved within the tumble of many other vernaculars that were birthed in the wake of a decaying empire, shifting political borders, fluid, newly reconstituting populations, and an ›interstitial cultural context‹.12 The language is not only written in the Hebrew alphabet; its difference to co-territorial vernaculars is also apparent linguistically. Taytsh has never been Daytsh (high German), though it literally means ›German‹, but it was the way for speakers to indicate that they were speaking a Germanic language.

Only in the late 19th century, ›Taytsh‹ and other names were replaced by ›Yiddish‹, literally meaning Jewish. Yehoshua Mordkhe Lifshitz, a father of the Yiddishist movement, chased political gains of normalizing Eastern European Jews within a teleological plot of national development when recasting the Eastern European vernacular as completely autonomous from both Hebrew and German and pronouncing it the Jewish people’s mame-loshn (mother tongue).13 This specific Yiddishist version of nationalism experienced its becoming through ideas of ›reviving‹ past traditions and ›returning‹ to lost glories ›regained‹ through racial purity and unified national identity. Having only the language but allegedly no autochthonous territory to claim in Europe, philology, the often unacknowledged ›parent and child of race theory‹,14 remained the primary means of returning to the allegedly lost origins.15 20th-century Yiddishists successfully mobilized philological theories to establish the paradigm of autonomous ›Jewish languages‹ and championed Yiddish as their most extreme example. Unlike Judeo-Arabic or Judeo-Italian, in Yiddish all is erased from the name but the ›Judeo‹ part synonymizing the language with Jewishness, as Zaritt has masterfully argued, and eliding the inherent linguistic (and implicitly cultural and social) interconnectedness with non-Jews.16

Yiddish scholars have recently invoked Taytsh in order to dissent from such Yiddish nationalism and to highlight, instead, the repressed history of (Jewish) cultures’ inherent translational mode and interconnectivity with the world that sustains and makes them. They point, inter alia, to the pedagogical practice of taytshn – the traditional word-to-word translation of the Pentateuch in the kheder, an institution of early Jewish education, where the teacher asks his pupils to provide the equivalent of the Hebrew in the Germanic register of Yiddish. In short, the name of the language equaled ›translation‹.17 Taytsh parts ways from Yiddish in the political project and history it can evoke. While the name Yiddish carries with it the ethnonational baggage of its 19th-century origins, Taytsh signifies that there existed and still exist alternative language practices – practices that invite its speakers’ multitudes, where it was and is not deemed necessary to demarcate one’s language as, in this case, a ›Jewish way of speaking‹, nor its speaker as having what we would today call a neatly encased ›Jewish identity‹.18 As such, Taytsh can explode our ideas about translation itself: those imaginaries of carrying over or moving across from one self-standing entity to the next, reproducing fraudulent notions of the autonomies of languages, cultures, and ›races‹.19

I use Taytsh, rather than Yiddish, to foreground these alternative visions that I detect to be enacted in Arendt’s language politics – even beyond Yiddish specifically and even, at times, against herself. For Arendt reactivates exactly the inherent pre-nationalistic, libidinally unbordered nature of language. We must start, however, with a short elaboration of the controversy itself. What and who was behind the outcry prompted by Arendt’s 1964 statement?

1. Jacques Derrida’s Misreading of Arendt

Arendt’s 1964 interview response aggrieved many, including Jacques Derrida. Buried in a six-page-long endnote of his 1998 memoir-cum-philosophical essay Monolingualism of the Other; or, The Prosthesis of Origin, the Jewish Algerian-French philosopher shadowboxes that ›German Jewish woman named Hannah Arendt‹, while banging his head against many of the questions at hand.20

Arendt is recruited in his text as a literal footnote, not important enough to merit inclusion in the body text as an interlocutor but, ironically, significant enough to epitomize the Other to the very image and history Derrida labored to inscribe himself into – a case, in short, of what Sigmund Freud would have probably diagnosed as ›narcissism of minor differences‹.21 Their spectral dispute hinges, most crucially, on Derrida’s and Arendt’s fundamentally different approaches to what the ›mother tongue‹ is and, all the more so, what it is to Jews: In Derrida, languages figure as objects of cultural property inextricably linked to one particular national tradition, commodities to which different people have profoundly asymmetrical access to deploy or weaponize. In other words, he accepts what Yasemin Yildiz has described as the ideology of monolingualism – a ›key structuring principle‹ according to which ›individuals and social formations are imagined to possess one »true« language only, their »mother tongue,« and through this possession to be organically linked to an exclusive, clearly demarcated ethnicity, culture, and nation‹.22 But Jews, in Derrida’s assemblage, are forever subaltern, vagabond subjects of eternal linguistic expropriation leaving them with only one language that will never be fully theirs. Arendt, in contrast, stresses ›that all languages are learnable‹,23 that they belong to all. Indeed, she accentuates in her affinity for the German language the practical head start she has in knowing German: ›In German I know a rather large part of German poetry by heart; the poems are always somehow in the back of my mind. I can never do that again.‹24

Importantly, Derrida arrives at his distorted conclusions about Arendt with the help of early 20th-century German-Jewish theologian and philosopher Franz Rosenzweig. His theories of ›Jews and »their« foreign languages‹ display the deep impact of the monolingual paradigm on Jewish thought and modernity writ large that had by the turn of the 20th century fed diverging debates in the Jewish world about the ›actual and ideal inter-relationship between Hebrew, Yiddish and the national languages of the states in which Jews lived‹.25 In Der Stern der Erlösung (The Star of Redemption), first published in 1921, Rosenzweig gives credence to the nativist idea that Jews are, by definition, not autochthonous to indeed any territory except ancient Palestine and deduces that, having lost Hebrew and Zion, ›the eternal people [...] everywhere speaks the language of its external destinies, the language of the people with whom it perchance dwells as a guest; [...] it never possesses this language in its own right, it never possesses it on the basis of its belonging to the same blood, but always as the language of immigrants who came from all over.‹26 No language, no land, and thus, we can deduce, no shared blood with non-Jews – having a host of scholars hand-wringing over the philosopher’s clear internalization of and engagement in contemporaneous ›race-thinking‹.27

Derrida, however, fails to see the family resemblance of this analysis to 18th- and 19th-century ideas most famously propagated by Nazi ideologues themselves. Jews were construed here, too, as relating to languages ›unnaturally‹ since they allegedly lacked, as eternal wanderers, not only a homeland but precisely the bloody ingredient that bakes the nation/›race‹: no investment in their own national language. Adoption of foreign languages was therefore deemed the Jewish weapon of infiltration and destruction from within. Yiddish was seen to support these corrupt hypotheses: not more than a degenerate ›jargon‹, gendered and raced, its uncategorizable hybridity displayed both the dangers of Jewish parasitism and the racial inferiority of its speakers.28

As an Algerian-French Jew, in his terms ›expropriated from‹ Hebrew, Yiddish or Ladino, and left only with ›a French of the colonized‹,29 Derrida confesses his envy of speakers of Yiddish (and Ladino) – a ›language of refuge that [...] would have ensured an element of intimacy, the protection of a »home-of-one’s-own« against the language of official culture‹.30 But it is exactly this identification of one language with an alleged ›essence‹ of the Jewish people (or of any people for that matter) that Arendt would have conceived as a dangerous adoption of the bankrupt nation-state paradigm. As she pointed out in the very interview Derrida tore to pieces, she understood her Jewishness as well as her mother tongue as an unchangeable, historically and socially contingent reality outside of concepts and demands pertaining to any nation and ›race‹.31 She had criticized the binding of language and national identity before vis-à-vis the radical project of assimilation of 19th-century German-Jewish elites and later Zionism: all of them parvenus who flee from the Jewish condition by ›not combatting her oppressors but identifying with them in several forms of mimetism‹.32 The adoption of the name Yiddish, as I have explained, displays a symmetry to these parvenu tendencies as well.

Unaware of these qualifications, Derrida, in his coup de main, betrays a certain (misogynist) disdain and misreading regarding Arendt’s ideas of ›monolingualism‹, far exceeding his empirically false assumption that she only read, only wrote, indeed, only thought in German.33 In fact, Arendt composed distinct English and German versions of nearly all of her books in addition to publishing in Yiddish and French; she incorporated her thorough knowledge of Latin and Greek, including in untranslated vocabulary; and her German literally stumbled into English in the course of defending her ›mother tongue‹ in the 1964 interview.34 Finally, Derrida chides her for failing to replace ›non-Jewish‹ German with ›either a sacred language [Hebrew] or a new idiom like Yiddish‹.35 He was wrong again, in many ways – for Arendt turned to Yiddish, repeatedly, but not as a refuge from German/ness, as he would have liked, but as an additional avenue for political action.

2. Learning Yiddish ›in spite of Hitler‹ (1936)

›My beloved wonder rabbi‹, Arendt commenced a 1936 letter from Geneva addressed to her future husband Heinrich Blücher in Paris, ›I am the only German Jew far and wide who has learned Yiddish. In spite of Hitler.‹36 Paris marked a turning point for her, away from philosophy towards politics, from now on approached through the matrix of the ›Jewish question‹.37 Apart from being active in all kinds of refugee activities in Paris, Arendt and Blücher were members of Walter Benjamin’s Marxist group of mainly German Jews. Chanan Klenbort, a Yiddish writer (pen name Khanan Ayalti), was the only Eastern European Jew within this German-Jewish exilic enclave and Arendt’s instructor in Yiddish (and Hebrew).38

Taytsh was somewhat mandated by her work as a secretary for the Agriculture et Artisanat – a Zionist organization that helped young Eastern European, often Yiddish-speaking, Jews to flee Poland and train in farming and crafts to best qualify for the scant immigration permits for Palestine.39 It was in this capacity that Arendt attended the first meeting convened for the creation of the World Jewish Congress in Geneva in 1936. ›Language of negotiation: Yiddish‹, she informed Blücher, ›and – Hebrew, the latter of which, according to all my very dull experiences of learning it, is not a language but a national misfortune! So, you better not let yourself be circumcised.‹40

Arendt’s ›Taytsh move‹, her queer turn to Yiddish as part of her grassroots activism to save lives rather than propping up nationalism, brings to mind the Russian-speaking founders of the Algemeyner yidisher arbeter-bund in Lite, Poyln un Rusland (General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia)41 or Russian-speaking socialist activists within the early American Labor movement of the late 19th century. These activists similarly realized that to organize the Jewish working class in the Russian empire or the United States, respectively, communication in Yiddish was essential. Many of them either did not know the language or had rejected it years prior as a marker of class status and cultural backwardness.42

Relieved from such ›language problems‹, however, Arendt categorized the Yiddish of the Jews living on German-speaking territory as a ›German dialect‹,43 reactivating, without spelling out literally, the new-old language practices and political visions that are embedded in Taytsh: she chose to speak, as influential medieval French rabbi Rashi put it in the 11th century, b’loshn Ashkenaz (in the language of Ashkenaz,44 namely German-speaking lands, applicable, depending on context, to Jews and non-Jews alike) and embraced this multidimensionality, interdependency, and dynamism. Although it is beyond the scope of my article to develop this argument fully, suffice it to say for now that we should consider Jewish-German language choices as another instance of a great linguistic migration such as that undertaken by a majority of lower-class non-Jewish Germans who similarly started out as speakers of Germanic vernaculars and acquired knowledge of ›high German‹ as part of the urbanization, industrialization, and state-building to which they were simultaneously subjected.45 Analytically, it allows for an entangled reading of class formation and racialization in the specific German context as historically and socially determined: language use, I argue, must be read in material rather than naturalized-identitarian terms. And in 1936, Arendt’s break with the German-Yiddish binary indeed went against the grain of the Zeitgeist.

The aforementioned Bundist and American Jewish labor activists initially justified their embrace of Yiddish as a short-term concession until linguistic assimilation to Russian or English, respectively, was achieved. However, Yiddish eventually became a core identitarian force and authentic cultural property to be refined and safeguarded alongside socialism for both groups. But turning to Yiddish became increasingly policed in the Europe of 1936, especially in the halls of high politics and specifically for German speakers, while the political practices of cross-cultural dialogue and kinship embedded in Taytsh became, out of political necessity, practices beyond the pale of imagination.

While Nazi Germany was on track to annihilate a majority of Yiddish speakers, the Zionist movement increasingly distanced itself from both German and Yiddish in favor of Hebrew; the languagesʼ Germanic core canceled them out for this monolingual project of creating the ›New Jew‹. What had always been an ideologically charged problem in regard to Zionism now turned unsolvable in the face of Hitler.46 The Yiddishist movement, the other monolingual Jewish project, understood with increased urgency the need to fully erect a wall between, as the protagonists saw it, the ›formerly‹ autonomous Yiddish and German. In 1938, influential Yiddishist philologist Max Weinreich – like Arendt, a German native speaker from the Baltics – who discarded the language fully in favor of Yiddish, invoked a Yiddish version of the infamous Ariernachweis (proof of ›Aryan‹ ancestry) explicitly for Yiddish language planning, implicitly for the making of the nation: ›Now that we have come to realize our linguistic and cultural powers, now that we approach our standardized kultur-shprakh [cultural language] with consciousness and love, every linguistic element must be put under quarantine. [...] A word in general, and all the more so if it is of New High German stock, has to demonstrate its right to be integrated into our standard language, has to prove that it has kinsmen among us, who take it into our family. Being a »registered person« [in a census, Yiddish: nikhtev] in our dictionary is not enough.‹47

These debates were far from simple rhetoric. Katharina Friedla has shown, for instance, how German-speaking Jewish refugees in the temporary safe haven of the Soviet Union frequently learned and turned to Yiddish as a rite of passage into the local Jewish communities but were repeatedly excluded because of their German inflection.48 It was not only in Nazi German, then, that the ›German Jew‹ became an ›impossible, untenable category‹49 – matched perhaps only by the category of the similarly unimaginable ›Arab Jew‹ several decades later.

It is beside the point to condemn, moralize or finger-wag. Under the conditions of war and genocide, it was understandable for most not to follow the Taytsh paradigm. But the privilege of many decades’ remove allows us to understand the larger implications of the above political choices and reveal the ideologies underpinning them. Arendt subverted these ideologies through her rescue activities in Yiddish. Her turn to Yiddish is therefore queer insofar as it disturbs this order and did not conform to the prevailing logic – it is, to borrow Lee Edelman’s words, ›a glitch in the function of meaning‹.50 Upon her arrival in New York in 1941, her ›Taytsh move‹ briefly entered the domain of Yiddish-language publishing.

3. ›Why it is hard for German Jews to adapt to the Yishuv‹ (1942)

Three Arendt-penned Yiddish articles have been unearthed so far,51 and I will discuss two that situate her language politics within the political climate and exhibit Arendt’s gradual disillusionment and eventual rupture with the Zionist movement. Rather than close readings, I will analyze the practical choice behind writing in Yiddish, the political contexts of their publications and the content of the articles themselves written to intervene in highly charged political debates about the relationship between monolingualism, Jewish nationhood, and ›race‹.

Hannah Arendt commented in 1942,

›and when they don’t speak Hebrew,

they also don’t switch to Yiddish.

And because the German Jews do not speak Yiddish,

they get discriminated against as non-Jewish Jews.‹

(excerpt from Hannah Arendt, Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on

shver zikh araynpasen in yishev, in: Morgen-zhurnal, November 1942)

In November 1942, Arendt published ›Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev‹ (Why it is hard for German Jews to adapt to the Yishuv) in the New York Yiddish newspaper Morgen-zhurnal.52 Here she flagged, already in 1942, that any language, but particularly the dogmatic Hebraism of the Zionist movement, inevitably assumes a proto-fascist bent when it becomes conflated with nationalism, identity politics, and a quest for power. But why did she choose to write it in Yiddish?

Contrary to common misconceptions, Yiddish was still in widespread use at the time of Arendt’s arrival in New York – as exemplified by the number of Yiddish periodicals, which far outnumbered Jewish journals in English. According to Anita Norich, such periodicals differed importantly in their orientation to Jewish identity and language politics: ›English journals […] generally proclaimed their [Jewish] particularism in their very titles; Yiddish journals, needing no such affirmation of their identity, were more apt to make eponymous claims to broader cultural concerns.‹53 This might help explain why Arendt deemed it necessary to perform the ›Taytsh move‹ in her early New York years. Yiddish was a major language of print media in the United States, an attractive venue for a public intellectual in the making. In addition to the scale of circulation, it also came attached to an audience more at risk in her view, because of the historically charged relationship to German, to the zero-sum logics of monolingualism (in this case Yiddish-centric) and the dangers of applying these same logics to German Jews. It was with this audience in mind that she explored and advocated for an alternative (Jewish) world-making beyond the nation-state.54

The writing of prolific New York-based Yiddish and Hebrew writer Arn Tseytlin provoked Arendt’s debut in Morgen-zhurnal. Tseytlin had written an intervention into debates about recent inter-Jewish conflicts in Palestine between Hebrew speakers (›us‹) and German speakers (›them‹).55 Such conflicts had long simmered following the uptick of German-Jewish migration (roughly 60,000 people in total) to Palestine from 1933 through the so-called ha-avara (transfer) agreement, a Faustian bargain that had been struck in 1933 between Nazi Germany and the Palestinian Zionist establishment facilitating immigration of German Jews along with the transfer of parts of their property to the Zionist enterprise.56 The hostility to German speakers by those committed to building a monolingual Hebrew state culminated in October 1942 when Hebrew-purist settlers bombed a printing house in which socialist and, according to Tseytlin, anti-Zionist German-language periodicals were printed.57 Morgen-zhurnal’s Tseytlin (in Yiddish) paraphrased the settler discourse for American audiences by laying most of the blame on the ›Blumental iden‹ themselves (Blumental Jews, referring to German Jewish refugees in Palestine) for failing to ›assimilate internally‹ (ineveynik), into Jewishness, due to their refusal to replace German with Hebrew.58 Prefiguring Gershom Scholem’s famous rebuke of Arendt in the wake of her Eichmann report twenty years later,59 Tseytlin traced this dearth of ›patriotism‹ to a German-Jewish, and therefore ›diasporic‹,60 lack of aaves-yisroel, namely love and solidarity for one’s fellow Jews.61 Aaves-yisroel appears neither in the Bible nor in rabbinic sources. Rather, Tseytlin’s usage is a modern example of a ›secularized idea‹, tied to the similarly modern idea of a Jewish nation, which was mythologized over time, akin to an ›invented tradition‹.62 Shira Kupfer and Asaf Turgeman have located the idea’s emergence in the 18th and 19th centuries.63 But Tseytlin ends on what is for him an optimistic note: German-speaking Jews will eventually become Jews again, once they let go of their alien Germanness.

Lest there be any doubt about her Yiddish skills, Arendt clearly followed the discourse in the Yiddish press attentively and decided to respond in Taytsh. Nonetheless, Yiddishist purists of the YIVO school would surely dismiss her article as displaying daytshmerisms (germanizing); others have suggested that a Yiddish speaker may have assisted her in the way that friends such as Randall Jarrell and Alfred Kazin did with English.64

Such discussions overlook what Haun Saussy has described as the ›performative contradiction‹ in Arendt’s exophonic text: it argues against one kind of assimilation and performs another incomplete kind, creolizing languages and thoughts, all the while demonstratively being the product of a ›conscious pariah‹ – namely without mimicking the linguistic structures of the acquired language to the point of self-effacement.65 There is a spectral quality to Arendt’s exophonic work where the cacophony of her multilingual practice and the acceptance of imperfection and ambiguity is an essential part of the deliberate exposure of a German-speaking Jewish outsider when performing the ›Taytsh move‹.66

Towering over the article, Arendt’s specific positionality is signified semiotically in her very name. Rather than the Hebraized form of Hannah as Khanah (חַ ּנָּה), a standard move in Yiddish for a traditionally Jewish name in Hebrew letters, her name appears phonetically as H-A-N-A-H (האַנאַה). The editor’s introduction presents Arendt as a ›well-known German-Jewish writer (shriftshtelerin) and Zionist activist‹ with necessary credentials and familiarity ›with the Yishuv and the New Aliyah‹ to boot.67 Out of ›Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev‹ then arises a critical constellation: Arendt makes an anti-Hebraist argument addressed to an American Yiddish-speaking audience in defense of the Taytsh paradigm of languages – namely a multilingual, anti-racist embrace of the plurality of Jewishness. This is her expression of Yishuvism. Originating from the Palestine Communist Party in the 1920s, Yishuvism became increasingly popular among the international Jewish antifascist left in the mid- to late 1940s. Understanding the struggle of the Jewish settlement in Palestine within the framework of global decolonial struggles and advocating for binational unity between the indigenous Arab and Jewish settler population against British, and later American, imperialism, Yishuvists campaigned for a Jewish community and its political/national rights in Palestine separate from Zionist doctrines.68

In the summer and fall of 1942, the British Mandate stood at a complicated historical juncture: while the systematic destruction of European Jews was well underway, a possible German invasion of Palestine was threatening to annihilate the growing – thanks to legal and illegal migration – Jewish settler population of nearly half a million people.69 In light of this, the local intra-Jewish hostilities towards the leftist German-language newspaper Orient, edited by Arnold Zweig and published in Haifa, may come as a surprise.70 Arendt was bewildered, too. ›I am of the opinion‹, she commented, that ›the Yishuv would be better off to boycott German goods than the German language and that its hotheads [hitskep] should have rather kept the bombs for [General Field Marshal Erwin] Rommel’s soldiers than to waste them against Jews of the German language. [...] It is simply absurd when the language of Jews from Germany can elicit a storm in Erets-Yisroel in a moment when the weapons of the Nazis from Germany threaten to annihilate the whole country and the whole Jewish people.‹71

She blames a ›lack of political consciousness‹ for these misdirected actions, so ›characteristic‹ of the Jewish people generally.72 Indeed, she continues, the accusations diagnosing a lack of Zionist affiliation among German migrants have no factual basis. German-Jewish immigration had contributed in outsized ways to the building of the Zionist enterprise, inter alia thanks to ha-avara-induced capital gains. Nor is the problem widespread resistance to abandoning the ›mother tongue‹. The true reasons for the attacks lay in the fact that ›German Jews have as their mother tongue [muter-shprakh] German and when they don’t speak Hebrew, they also don’t switch to Yiddish. And because the German Jews do not speak Yiddish, they get discriminated against as non-Jewish Jews.‹73

What I argue we can read into this statement is that Arendt turns Rosenzweig’s language typologies against themselves and casts the continued existence of the Jewish people as proof of the inadequacy of fascist ›language, blood, and soil‹ ideologies for a political movement that should be committed to liberating the world from ›race‹ as an organizing principle. Zionism, instead, chose to become the gravedigger of Jewish plurality.74 What Arendt detects as the parallel between fascist ideologies and Zionism is the purging of German Jews from the body politic: rendering them racially non-Jewish and naturalizing the German-Jewish binary. In that (and in addition to rendering Palestinians a pariah people), the Zionist project enacts the racism of a fascistic world order75 at a time when ›[f]ew things are as important for our current politics as to keep oppressed people’s struggles for liberation free from the plague of fascism‹.76

Fittingly, Arendt concludes with the issue of class struggle as the overarching principle which governs the interaction of manifold struggles. This might be surprising, as she famously rejected ›the social‹ as political in her later work.77 But the core issues of the ›language question‹ in Palestine, according to Arendt in Taytsh, are the legacies of the class formation(s) of European Jewry that now clash: German Jews pulled gravitationally towards the bourgeoisie in Germany and then the imperial class of Britain78 in Palestine and were alienated from the Jewish working class (speaking Yiddish/Hebrew, etc.). By extension, they were alienated from Jewish nation-building ambitions.79 Gesturing towards later, much more fleshed-out elaborations on the dangers of the transitioning from colony to postcolony by such radical thinkers as Frantz Fanon, Arendt warns precisely of this structural divergence from the ›common man‹ (posheter mentsh) – who is ›the real center of politics‹ in ›any democratic country‹ – and his national aspirations. Where Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth called on the ›national middle class [...] to consider as its bounden duty to betray the calling fate has marked out for it, and to put itself to school with the people‹,80 Arendt similarly urged that ›the German Jews [be taught] respect for the common people generally and the Jewish folk (folks-mentsh) specifically‹, that is to politically educate them – ›and [...] [t]he most beautiful Hebrew won’t be able to teach this‹.81 Indeed, implicitly taking herself as the prime example, it is political action with and for the oppressed in any relevant language that can create the conditions for liberation. And yet, this affinity to Fanon’s thought should give us pause. So contradictory to her famous condemnation of what she falsely construed as his incitement of violence in On Violence,82 it only accentuates her political realignment over time.

In as late as 1942, Arendt suggests that neither an abandonment of German by German Jews nor the top-down stamping out of German-Jewish language culture as a superficial symptom can be a cure for these fundamental contradictions. Rather, in a Taytsh way, a reorientation of political alliances from bourgeois nationalism to the international working class (including Arab workers) in the fight against fascism and imperialism is essential. Clearly, for those on the left, like Arendt, critical of Zionism but generally in favor of Jewish self-determination, Palestine’s extreme heterogeneity of political agendas in 1942 still suggested many roads away from a Jewish ethno-state. In the face of two catastrophic world wars, Arendt confided to Gershom Scholem in 1946 that ›the nation, or better put, the nation-state as an organization of peoples‹ was irreversibly ›dead‹.83 The alternative for her lay, as Enzo Traverso so aptly put it, ›in a dissociation between the state form and the principle of nationality‹.84 Arendt’s ›Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev‹ anticipates her (temporary) turn to a socialist tradition of a supranational community in the form of federated, locally-based council systems.85 Language as the marker of Jewish and human plurality played a crucial role in this: ›Jewish politics‹ must be pursued ›in all languages of the world‹, as she herself actively tried to prove.86

Hidden in the piece is the concept of the ›Jew of the German language‹. We may read her reconceptualization as an attempt to decouple German Jews from the German nation-state while tying them to a nation-transcending language instead: an internationalist one. Stephan Braese has pointed to the importance of German within German-Jewish language cultures as embodying an international ideal of Europeanism.87 In the 1930s and 1940s, with thousands upon thousands of German-speaking émigré circles worldwide, this culture became indeed an international phenomenon when German, just like Yiddish, gained the status of a lingua franca of global antifascism.88 Several months after this Yiddish op-ed, Arendt’s English essay ›We Refugees‹ took these ideas even further by heralding ›[r]efugees driven from country to country‹ as ›the vanguard of their peoples – if they keep their identity‹ and not bend to the demands of linguistic assimilation.89

4. ›What should become of Germany?‹ (1944)

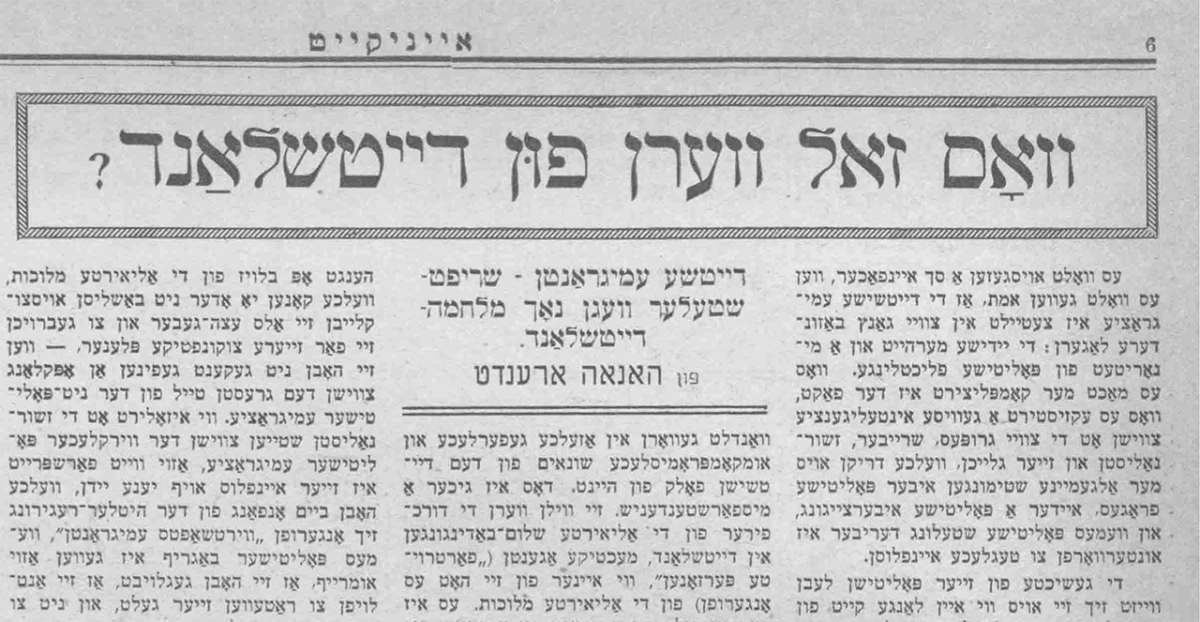

One expression of international Yiddish antifascism was the New York journal Eynikayt (Unification)90 – the site of Arendt’s last known Yiddish publication: ›Voz zol vern fun Daytshland?‹ (What should become of Germany?).91 Ostensibly about Germany’s future, the article was in fact making a federalist case for the future of Europe after the nation-state. Crucially, unlike the German language, Germany, to her, is dead for good.

The organ of the American Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists and Scientists (ACJWAS), a pro-Soviet American organization operative in New York since 1941, Eynikayt took its name from the Soviet publication Eynikayt of the Moscow-based Jewish Antifascist Committee (JAFC). According to ACJWAS chairman Chaim Zhitlovsky, a Yiddish socialist political thinker and activist, the American Committee saw itself as a complement to the Soviet one with a twofold purpose: to mobilize for material help for the Soviet war effort as well as to build bridges between the American and Soviet Jewish communities.92 Part of these efforts was to win over American liberals and leftists. ACJWAS recruited Communist Party members, fellow travelers, and liberal writers such as American novelist Howard Fast, playwright Arthur Miller, and German-Jewish émigré writer Lion Feuchtwanger.93 Arendt probably didn’t need much persuasion: in 1944, at the time of her article’s publication, she was surprisingly supportive of both Soviet federacy and Soviet Jewry. She had just witnessed a Soviet Jewish newsreel ›To World Jewry‹ broadcasted from Moscow in August 1941 starring three representatives of the JAFC, namely famed Soviet Yiddish actor Shloyme Mikhoels, Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein, and Soviet Yiddish poet Perets Markish, and appealing to the audiences ›to unite in the struggle against Hitler and fascism‹.94

Mixing as they did English, Russian, and Yiddish in the newsreel, doing Jewish politics ›in all languages of the world‹ as it were, Arendt in fact saw Soviet Jewry as representing vanguards in Jewish politics since, as she would explain in two consecutive Aufbau op-eds in 1942, ›they are the first Jews to be emancipated as a nationality and not as individuals‹. Stemming from Soviet nationality policies and the outlawing of antisemitism, she continued approvingly, ›the Russian Revolution has carried the emancipation begun with the French Revolution to its logical conclusion‹.95 Through such policies, Arendt wrote, the Soviet Union ›found an entirely new and – as far as we can see today – an entirely just way to deal with nationality or minorities. This new historic fact is this: that for the first time in modern history, an identification of nation and state has not even been attempted.‹96 Retrospectively seen by many as a naive optimism towards the Soviet project and indeed surprising given her deep criticism of the Soviet Union only a few years later,97 for her to publish with Eynikayt at this specific moment of antifascist unity made a lot of sense.

In ›Voz zol vern fun Daytshland?‹, Arendt traces the ways in which German-Jewish émigré parvenus tried (and failed) to fit into their new national contexts, this time in the United States. Some didn’t ›speak as Jews or for the Jewish people but discovered in their Jewishness a very comfortable means to rid themselves of their German origin (Geburt)‹. Others wanted nothing to do with Germany and were ready to excommunicate (kheyrem) any Jew that returned to Germany or spoke the German language. By my reading both responses fall under what Karen and Barbara Fields have termed ›racecraft‹:98 by naturalizing the idea of ›race‹ and internalizing its zero-sum logic, their Jewishness necessarily cancels out the very possibility of being German, i.e. of living in multitudes.

By contrast, Arendt centers various factions of political émigrés (politishe emigratsye) in the U.S. who do not think in these racist categories and speak of Germany with a larger socialist post-war conception of Europe in mind. The vanguards of this group, German-language leftist writers Bertolt Brecht, Alfred Döblin, Franz Werfel, Lion Feuchtwanger et al., considered themselves representatives of 1944 European culture, despite living in the United States, and as extensions of the various resistance movements under German occupation. Aiming to lay the foundations of a ›democracy with socialist laws‹ in a European federation, Arendt explains, political émigrés demanded the elimination not only of Nazi bureaucracy but of its very underlying structures: big industry, militarism, land-owning aristocracy.99

The implosion of the diasporic center/periphery binary in the image of a world federacy is matched by the implosion of the jealous demands on a Yiddish text. Arendt’s ›Voz zol vern fun Daytshland?‹ is a performance of Taytsh insofar as it deliberately escapes the strict rule of ›Jewish texts‹: to advance exclusively Jewish causes. Instead, it addresses, at least in theory, many readers at once, Jewish and not, and expresses, politically, a will to mediate between communities for human liberation. In that, the text ›continually arrives elsewhere‹, as Saul Zaritt so beautifully described the process of Taytsh, ›rather than on a single shore of national solidarity or subaltern subjugation‹.100

5. In/Conclusion: The Thesis of Taytsh

On 12 November 1965, almost exactly twenty-three years to the day after the publication of ›Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev‹, Arendt received a belated response from Arn Tseytlin in Morgen-zhurnal.101 His ›Fun fraytog biz fraytog: A bukh vegen Eykhman-protses‹ (From Friday to Friday: A Book about the Eichmann Trial) maps one controversy, Eichmann in Jerusalem, onto the other, Arendt’s German. Technically what Tseytlin penned was a celebratory review of Jacob Robinson’s And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight. The Eichmann Trial, the Jewish Catastrophe, and Hannah Arendt’s Narrative102 – in actual fact an attempt at refuting Arendt’s trial report. Tseytlin pans the spotlight not on Robinson, but on Arendt: as the ›devil’s advocate‹ (tayvel-advokat), she allegedly reversed the order of the world of good (Jews) and evil (Nazis). Totalizing dichotomies between goyish enemy and Jewish victim,103 the language of monsters and the language of tsadikim (righteous), structure Tseytlin’s review to the point that Arendt, not once mentioned by name and construed as fully switching ›national‹ loyalties, is excommunicated from Jewishness by symbolically ›removing her‹, to borrow Richard I. Cohen’s words, ›from the book of life‹.104 The parallel to Tseytlin’s 1942 ›Shturm in’m Erets Yisroel yishev iber di »Blumental iden«‹ [Storm on the ›Blumental Jews‹ in the Erez Israel settlement], his censorial nationalism, its circularity concerning German and guilt by association with Nazism, is indeed striking. But things had changed by 1965 – for Arendt.

A year later, in a response, she meticulously traced Robinson’s numerous falsifications and deliberate distortions of her Eichmann in Jerusalem for the New York Review of Books, pulling the rug out from under Tseytlin’s defamation and German-Jewish binary in the same stroke without mentioning him by name either.105 On the one hand, her nuanced Eichmann analysis of Nazism, how it implicated, structurally, its victims,106 builds upon the foundation of her 1940s Taytsh writings. On the other, her language politics reveal an antifascist, anti-racial, Yishuvist-inspired conception of Jewishness that goes against Yiddishist and Zionist monolingualism. They open up radical potentials in the darkest hour of European history.

I could rest my case here if it weren’t for Arendt’s later works, a full treatment of which is outside the scope of this article, but which are important to address briefly. Paradoxically, even though her ›Taytsh move‹ was instrumental in breaking free from static, reductive conceptions of Jewishness towards envisioning a world where ›every individual [is] able to decide what he would like to be, German or Jew or whatever‹ and in which ›everyone can choose freely where he would like to exercise his political rights and responsibilities and in which cultural tradition he feels most comfortable‹,107 her Cold War years introduced an awkward Jewish exceptionalism against the backdrop of a pathologization of non-white and non-European projects of liberation. Samuel Moyn has recently situated Arendt as a strange bedfellow of Cold War liberals, especially in their ›civilizational and indeed racial restriction of the possibilities of freedom in a decolonizing world‹.108 With the crystallization of the Cold War in 1947–48, Arendt gradually departed from the disciplined practice of Taytsh: she converted her belief in the French and Russian revolutionary tradition, as expressed in her 1940s work on Palestine and Europe, to an ›explicitly globalizing skepticism‹ of its ›violent‹ legacies.109

Arendt’s defamation of Black American civil rights politics is intertwined with the abandoning of Taytsh and thus figure at the heart of this contradiction. Meditating on the struggles to create a Black Studies curriculum at American universities, she warns that ›even more frightening is the all too likely prospect that, in about five or ten years, this »education« in Swahili (a 19th-century kind of no-language spoken by the Arab ivory and slave caravans, a hybrid mixture of a Bantu dialect with an enormous vocabulary of Arab borrowings; see the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1961), African literature, and other nonexistent subjects will be interpreted as another trap of the white man to prevent Negroes from acquiring an adequate education.‹110 Echoing the classic degradation of Yiddish as a non-language for practically the same reason, hybridity, Arendt’s Taytsh, exposing the ways in which language is instrumental in socially reproducing ›race‹ itself, came to a premature end.

These contradictions between her 1940s Yiddish works and her much-criticized writings in the 1960s and 1970s are a reminder that modern ways of thinking about peoplehood, identity, territory and the role languages and language ideologies play in constituting and maintaining them are powerful but never total, that departing from them needs to be manifested continuously if the liberation (or, minimally, the theorization of liberation) of all oppressed indeed remains one’s goal. The possibility of Taytsh alerts us to the fact that there is room to navigate and escape their gravitational pull to separate, classify, and rank.

Thinking with, against, and beyond Arendt about German after Hitler through Yiddish allows a reimagining of the kinship between (these) languages and an unsettling of their artificial, racialized separation. It acts in defiance of the Holocaust’s Jewish-German binary, and, by extension, the Yiddish-German binary – reified binaries Arendt at her best can still help us in breaking down.

In 1951, Arendt published one of her most famous works, The Origins of Totalitarianism, ushering in her stint as a disjointed fellow traveler of Cold War liberals. Forgotten were her 1940s Soviet affinities, when the Soviet project now figured as an equivalent of Nazism. But even though much of the radical potential expressed in Arendt’s Yiddish articles was gradually replaced by her more famous commentaries, we can still find traces of Taytsh – specifically when it comes to language – in the privacy of her Denktagebuch (Thought Diary): ›By the fact that the object, which is there for the supporting presentation of things, can be called Tisch [and in Yiddish tish] as well as »table« [English and French], it is implied that we miss something of the true essence of what we ourselves produce and name. [...] This fluctuating ambiguity of the world and the uncertainty of man in it would not exist, of course, if there were not the possibility of the learnability of the foreign language, which proves to us that there are other »correspondences« to the common identical world than ours, or if there were even only one language. [...] Hence the nonsense of the world language – against the ›condition humaine‹, the artificially violent unification [Vereindeutigung] of the ambiguous [des Vieldeutigen].‹111

As readers of Arendt, we are not bound to her biography. We can take all the radical implications of Taytsh to resist the fascistic co-constitution of language, nation, and ›race‹ – now more urgent than ever. And while Arendt limits her thoughts in this 1950 excerpt to language, we can revive the spirit of her Yiddish articles and see the glimmers of solidarity as we all sit at the same tish in order to taytsh.

Notes:

1 For examples of using Arendt as a generative source, at times despite herself, see Richard J. Bernstein, Why Read Arendt Now, London 2018, p. 52; Michael Weinman, Thinking with and Against Arendt About Race, Racism, and Anti-Racism. Beyond Origins and »Reflections«, in: Arendt Studies 6 (2022), pp. 75-87; Juliane Rebentisch, Der Streit um Pluralität. Auseinandersetzungen mit Hannah Arendt, Berlin 2022; Marilyn Nissim-Sabat/Neil Roberts (eds), Creolizing Hannah Arendt, Lanham 2024.

2 Translation altered for accuracy by author. Hannah Arendt, »What Remains? The Language Remains«: A Conversation with Günter Gaus, in: Arendt, Essays in Understanding, 1930–1954. Formation, Exile, and Totalitarianism, ed. by Jerome Kohn, New York 1994, pp. 1-23, here p. 12. The original interview (plus English subtitles) can be seen at YouTube.

3 Arendt’s ›Eichmann in Jerusalem‹ was first published in five consecutive issues in The New Yorker in 1963. The book version Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil appeared in the same year (New York: Viking Press/London: Faber & Faber). Piper published the first German edition in 1964.

4 See, e.g., Lionel Abel, More on Eichmann, in: Partisan Review 31 (1964), pp. 270-275, here pp. 270-271.

5 Weissberg similarly identifies a causal relation between the Eichmann controversy and the Gaus interview; see Liliane Weissberg, In Search of the Mother Tongue: Hannah Arendt’s German-Jewish Literature, in: Steven E. Aschheim (ed.), Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem, Berkeley 2001, pp. 149-164, here p. 150; further Stephan Braese, Hannah Arendt und die deutsche Sprache, in: Ulrich Baer/Amir Eshel (eds), Hannah Arendt zwischen den Disziplinen, Göttingen 2014, pp. 29-43.

6 Adam J. Sacks, Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann Controversy as Destabilizing Transatlantic Text, in: AJS [Association for Jewish Studies] Review 37 (2013), pp. 115-134, here p. 123.

7 There has been a lot of interesting work done on Arendt’s alleged racism (chiefly in: Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Vol. II, New York 1951; Hannah Arendt, Reflections on Little Rock, in: Dissent 6 [1959], pp. 45-56) as well as readings against this. The pivotal collections include Richard H. King/Dan Stone (eds), Hannah Arendt and the Use of History. Imperialism, Nation, Race, and Genocide, New York 2008; Kathryn T. Gines, Hannah Arendt and the Negro Question, Bloomington 2014; Vaughn Rasberry, Race and the Totalitarian Century. Geopolitics in the Black Literary Imagination, Cambridge 2016; Ainsley LeSure, The White Mob, (In)Equality Before the Law, and Racial Common Sense: A Critical Race Reading of the Negro Question in »Reflections on Little Rock«, in: Political Theory 49 (2021), pp. 3-27; Niklas Plaetzer, Refounding Denied: Hannah Arendt on Limited Principles and the Lost Promise of Reconstruction, in: Political Theory 51 (2023), pp. 955-980.

8 On the monolingual paradigm, see Yasemin Yildiz, Beyond the Mother Tongue. Toward the Postmonolingual Condition, New York 2012.

9 Samuel Moyn, Liberalism Against Itself. Cold War Intellectuals and the Making of Our Times, New Haven 2023, pp. 115-139; further A. Dirk Moses, The Problems of Genocide. Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression, New York 2021.

10 The legacy of this false equation lives on in, inter alia, today’s corrupt ›horseshoe theories‹.

11 Saul Zaritt, A Taytsh Manifesto: Yiddish, Translation, and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture, in: Jewish Social Studies 26 (2021) issue 3, pp. 186-222, here p. 205; the book-length version of Zaritt’s study is forthcoming with Fordham University Press in October 2024.

12 Jerold C. Frakes, The Emergence of Early Yiddish Literature. Cultural Translation in Ashkenaz, Bloomington 2017, vii; further Jerold C. Frakes, The Politics of Interpretation, Albany 1989, pp. 21-105; Jeffrey Shandler, Yiddish. Biography of a Language, Oxford 2020, pp. 6-16, 48-58; on the difficulties of this linguistic relationship for Jewish nationalism, see Marc Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem. The Language Politics of Jewish Nationalism, Stanford 2020, specifically pp. 173-199.

13 Yehoshua Mordkhe Lifshitz, Di fir klasn, in: Kol mevaser [Herald], 1 July 1863, pp. 364-366. For a thorough discussion of the essay, see David E. Fishman, Di dray penimer fun Y-M Lifshitz (an analiz fun ›Di fir klasn‹), in: Yidishe shprakh 38 (1984–1986), pp. 47-58; further Miriam [Chorley-]Schulz, For Race is Mute and Mame-loshn can Speak: Yiddish Philology, Conceptions of Race, and Defense of Yidishkayt, in: Judaica Petropolitana 5 (2016), pp. 98-127, here pp. 107-108; Emanuel S. Goldsmith, Modern Yiddish Culture. The Story of the Yiddish Language Movement, New York 1997, p. 47.

14 Christopher M. Hutton, Linguistics and the Third Reich. Mother-tongue Fascism, Race and the Science of Language, London 1999, p. 3.

15 I am drawing here on Slavoj Žižek, Absolute Recoil. Towards a New Foundation of Dialectical Materialism, London 2014, specifically: The Violence of the Beginning.

16 Zaritt, Taytsh Manifesto (fn 11), p. 187. For the original source of the ›Jewish Language‹ paradigm, see Max Weinreich, History of the Yiddish Language, Vol. 1, New Haven 2008, pp. 66-69 (the first edition in Yiddish had been published in 1973, the first edition in English in 1980). On the entanglement of Yiddishism with race science, see [Chorley-]Schulz, For Race is Mute and Mame-loshn can Speak (fn 13); Barry Trachtenberg, Ber Borochov’s »The Tasks of Yiddish Philology«, in: Science in Context 20 (2007), pp. 341-352.

17 Zaritt, Taytsh Manifesto (fn 11), p. 201; Barry Davis, Yiddish: The Perils and Joys of Translation, in: European Judaism. A Journal for the New Europe 43 (2010) issue 1, pp. 3-36, here pp. 3-4.

18 Zaritt, Taytsh Manifesto (fn 11), pp. 188, 192, 194.

19 ›Race‹ appears in quotation marks because it is the underlying premise of this article that ›races‹ do not exist but are socially constructed. Racism produces ›races‹. The steadily growing corpus of works on this topic cannot be reviewed here. For helpful analysis, see Karen E. Fields/Barbara J. Fields, Racecraft. The Soul of Inequality in American Life, New York 2012.

20 Jacques Derrida, Monolingualism of the Other; or, The Prosthesis of Origin, trans. Patrick Mensah, Stanford 1998, pp. 84-90, here p. 84.

21 Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, New York 2010, p. 305 (first published in German and English in 1930). Freud counts antisemitism itself among this form of narcissism; see Sigmund Freud, Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion [1939], Frankfurt a.M. 2013, p. 197.

22 Yildiz, Beyond the Mother Tongue (fn 8), p. 2.

23 Hannah Arendt, Denktagebuch 1950–1973, Vol. 1, ed. by Ursula Ludz and Ingeborg Nordmann, Munich 2016, p. 42.

24 Arendt, »What Remains? The Language Remains« (fn 2), p. 13.

25 Hutton, Linguistics and the Third Reich (fn 14), p. 188.

26 Franz Rosenzweig, The Star of Redemption, trans. Barbara E. Galli, Madison 2005, p. 320.

27 See Haggai Dagan, The Motif of Blood and Procreation in Franz Rosenzweig, in: AJS Review 26 (2002), pp. 241-249; Peter Gordon, Rosenzweig and Heidegger. Between Judaism and German Philosophy, Berkeley 2003, pp. 210-214; David Biale, Blood and Belief. The Circulation of a Symbol Between Jews and Christians, Berkeley 2007, pp. 200-205; Leora Batnitzky, Idolatry and Representation. The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig Reconsidered, Princeton 2009, pp. 62-79. Interestingly, Rosenzweig’s ideas about Jewish relations to language have been making a curious comeback in recent years in explicitly anti-Zionist projects. See Tal Hever-Chybowski, Mikan Ve’eylakh (From this Point Onward): Foreword. Translation by Rachel Seelig, in: In geveb. A Journal of Yiddish Studies, 30 April 2018; Daniel Boyarin, The No-State Solution. A Jewish Manifesto, New Haven 2023.

28 Yiddish was deemed by mainstream 19th-philology unclassifiable and its status of language questioned for a long time. Its alleged defects were framed as exposing the deficiencies of its speakers. Further on this, see Christopher M. Hutton, Normativism and the Notion of Authenticity in Yiddish Linguistics, in: David Goldberg (ed.), The Field of Yiddish. Studies in Language, Folklore and Literature, Evanston 1993, pp. 14-28, here p. 28; Arndt Kremer, Deutsche Juden – deutsche Sprache. Jüdische und judenfeindliche Sprachkonzepte und -konflikte 1893–1933, Berlin 2007, pp. 90-160; on the long history of Yiddish linguistics and its effect on Jews, see Aya Elyada, A Goy who Speaks Yiddish. Christians and the Jewish Language in Early Modern Germany, Stanford 2012, pp. 81-121; Sander L. Gilman, Jewish Self-Hatred. Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews, Baltimore 1986, pp. 70-81.

29 Derrida, Monolingualism of the Other (fn 20), p. 84. Emphasis in the original.

30 Ibid., p. 54.

31 Arendt, »What Remains? The Language Remains« (fn 2), p. 8; for further proof of this, see Hannah Arendt to Gershom Scholem, 20 July 1963, in: Arendt/Scholem, The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem, ed. by Marie Luise Knott, trans. Anthony David, Chicago 2017, pp. 206-207. Arendt’s rejection of the Nazi linguistics embodied by Carl Schmitt has been explored elsewhere; see Ville Suuronen, Nazism as Inhumanity: Carl Schmitt and Hannah Arendt on Race and Language, in: New German Critique 49 (2022) issue 2, pp. 15-48.

32 Regarding this symmetry, see Enzo Traverso, The End of Jewish Modernity, London 2016, p. 70.

33 I am not the first to explore Derrida’s profound misunderstanding of Arendt; see e.g. Jennifer Gaffney, Can a Language Go Mad? Arendt, Derrida, and the Political Significance of the Mother Tongue, in: Philosophy Today 59 (2015), pp. 523-539.

34 The ongoing critical edition hybrid publication project is the first to present all of Hannah Arendt’s published and unpublished multilingual works in a philologically reliable scholarly edition with critical commentary; see further Barbara Hahn, Die »eigene» und andere Sprachen, in: Dorlis Blume/Monika Boll/Raphael Gross (eds), Hannah Arendt und das 20. Jahrhundert, Munich 2020, pp. 147-154.

35 Derrida, Monolingualism of the Other (fn 20), p. 84.

36 Hannah Arendt to Heinrich Blücher, 24 August 1936, in: Arendt/Blücher, Briefe 1936–1968, ed. by Lotte Köhler, Munich 1996, p. 58.

37 Cf. Traverso, The End of Jewish Modernity (fn 32), Chapter 4: Between Two Epochs: Jewishness and Politics in Hannah Arendt; further Thomas Meyer, Hannah Arendt. Die Biografie, Munich 2023, pp. 103-206 (»›Zu 100 Prozent jüdisch‹ – Pariser Jahre«).

38 Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt. For Love of the World, New Haven 1982, pp. 118-119, 122.

39 Young halutzim (Zionist pioneers) with agricultural expertise were the preferred settlers for the new society; see Tom Segev, The Seventh Million. The Israelis and the Holocaust, trans. Haim Watzman, New York 1993, p. 43.

40 Hannah Arendt to Heinrich Blücher, 8 August 1936, in: Arendt/Blücher, Briefe 1936–1968 (fn 36), p. 39.

41 David Fishman, The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture, Pittsburgh 2005; Frank Wolff, Yiddish Revolutionaries in Migration. The Transnational History of the Jewish Labor Bund, trans. Loren Balhorn and Jan-Peter Herrmann, London 2021.

42 Tony Michels, A Fire in Their Hearts. Yiddish Socialists in New York, Cambridge 2021.

43 Hannah Arendt to Kurt Blumenfeld, 31 July 1956, in: Arendt/Blumenfeld, »... in keinem Besitz verwurzelt«. Die Korrespondenz, ed. by Ingeborg Nordmann and Iris Pilling, Hamburg 1995, pp. 148-152, here p. 151.

44 The Hebrew term Ashkenaz refers to an unknown region in biblical geography. Rabbinic figures mapped it onto a contemporary European landscape. Ashkenaz designates both Central and Eastern Europe and stretches beyond its boundaries as a disembodied Jewish space. See Zaritt, Taytsh Manifesto (fn 11), who refers to Ross Perlin, Searching for Ashkenaz, in: In geveb. A Journal of Yiddish Studies, 17 June 2016.

45 This goes against the claims made in: Shulamit Volkov, Sprache als Ort der Auseinandersetzung mit Juden und Judentum in Deutschland, 1780–1933, in: Wilfried Barner/Christoph König (eds), Jüdische Intellektuelle und die Philologien in Deutschland 1871–1933, Göttingen 2001, pp. 223-238, here p. 231; Stephan Braese, Eine europäische Sprache. Deutsche Sprachkultur von Juden 1760–1930, Göttingen 2010, p. 14, fn 20.

46 Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem (fn 12), pp. 200-229.

47 Max Weinreich, Daytshmerish toygt nit, in: Yidish far ale 4 (June 1938), pp. 97-106, here p. 105.

48 Katharina Friedla, ›Bist a Yid? Can’t you speak to me in Yiddish?‹: Yiddish as a marker of identity among Polish Jews in the Soviet Union, in: Miriam Chorley-Schulz/Alexander Walther (eds), Socialist Yiddishlands. Language Politics and Transnational Entanglements between 1941 and 1991, Düsseldorf 2024 (forthcoming), pp. 49-62.

49 Franz Rose, ›Polnischer Jude‹ oder ›Jude polnischer Staatsangehörigkeit‹, in: Deutsche Presse 28 (1938), pp. 454-455; cited in: Thomas Pegelow Kaplan, The Language of Nazi Genocide. Linguistic Violence and the Struggle of Germans of Jewish Ancestry, Cambridge 2009, pp. 104, 120.

50 Lee Edelman, Bad Education. Why Queer Theory Teaches Us Nothing, Durham 2022, xvi.

51 I exclude ›Di idishe armee – der onheyb fun idisher politik?‹ (The Jewish Army – The Beginning of Jewish Politics?), an anonymous translation of Arendt’s Aufbau op-ed which was published in the News Bulletin of the Emergency Committee for Zionist Affairs in December 1941. See Hannah Arendt Papers, Speeches and Writings File, 1923–1975, Essays and Lectures, ›Die jüdische Armee – Der Beginn einer jüdischen Politik?‹, essay in Yiddish, 1941. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, URL: <https://www.loc.gov/item/mss1105601236/>.

52 Hannah Arendt, Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev, in: Morgen-zhurnal, November 1942. Na’ama Rokem, in collaboration with Sunny Yudkoff, wrote a very helpful analysis of this piece but focused primarily on Arendt’s identity formation and relationship to Zionism. See Na’ama Rokem, Hannah Arendt and Yiddish, in: Amor Mundi, 18 February 2013.

53 Norich counts at least twenty-nine Yiddish cultural journals as opposed to thirteen English journals with a Jewish focus: Anita Norich, »Harbe Sugyes/Puzzling Questions«: Yiddish and English Culture in America during the Holocaust, in: Jewish Social Studies 5 (1998/99) issue 1-2, pp. 91-110, here p. 93.

54 On Arendt’s ambition to pursue political projects beyond the faulty nation-state paradigm and her impact on later thinkers, see, e.g., Anya Topolski, Nation-States, the Race-Religion Constellation, and Diasporic Political Communities: Hannah Arendt, Judith Butler, and Paul Gilroy, in: European Legacy 25 (2020), pp. 266-281.

55 Arn Tseytlin, Shturm in’m Erets Yisroel yishev iber di »Blumental iden«, in: Morgen-zhurnal, 23 October 1942, pp. 5, 7.

56 Segev, The Seventh Million (fn 39), pp. 20-64; Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem (fn 12), pp. 200-229.

57 Cf. Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem (fn 12), p. 206; Rokem, Hannah Arendt and Yiddish (fn 52). Between 1933 and 1945, a third of the approximately 700,000 German-speaking Jewish citizens of Germany and Austria were murdered by the Nazi regime and its helpers, and the rest were able to flee or to go into hiding. Only 10 percent went to Palestine, which amounts to a mere 20 percent of all refugees arriving there between 1933 and 1945; see Segev, The Seventh Million (fn 39), p. 35.

58 Tseytlin, Shturm in’m Erets Yisroel yishev (fn 55), p. 5.

59 Hannah Arendt, The Eichmann Controversy: A Letter to Gershom Scholem [1964], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings, ed. by Jerome Kohn and Ron H. Feldman, New York 2007, pp. 465-471, here pp. 466-467.

60 While Tseytlin is taking up the term in the more common usage of the Jewish diaspora implicitly with Zion as a national home, the German Jews he refers to, though surely not all of them, considered refugeedom in Palestine as equivalent to living in the German diaspora.

61 I am drawing here on Na’ama Rokem, who identified this recurring theme of ahavat israel; see Rokem, Hannah Arendt and Yiddish (fn 52).

62 Eric J. Hobsbawm/Terence Ranger (eds), The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge 1983.

63 Shira Kupfer/Asaf Turgeman, The Secularization of the Idea of Ahavat Israel and Its Illumination of the Scholem-Arendt Correspondence on Eichmann in Jerusalem, in: Modern Judaism 34 (2014), pp. 188-209.

64 Rokem, Hannah Arendt and Yiddish (fn 52).

65 Haun Saussy, The Refugee Speaks of Parvenus and Their Beautiful Illusions: A Rediscovered 1934 Text by Hannah Arendt, in: Critical Inquiry 40 (2013/14), pp. 1-14, here p. 14.

66 Arendt, Denktagebuch (fn 23), p. 42.

67 All citations from Arendt, Farvos (fn 52). Aliyah Chadashah (new emigration) refers to a political party formed by German emigrants to Palestine; see Curt D. Wormann, German Jews in Israel: Their Cultural Situation Since 1933, in: Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 15 (1970), pp. 73-103, here p. 83.

68 Here I am following the excellent exploration of the prevalence of Yishuvism in Jewish left-wing circles in the 1940s by Max Kaiser, Jewish Antifascism and the False Promise of Settler Colonialism, Cham 2022, pp. 104-114; further on Yishuvism, see Musa Budeiri, The Palestine Communist Party, 1919–1948, Chicago 2010, p. 9.

69 Klaus-Michael Mallmann/Martin Cüppers, »Elimination of the Jewish National Home in Palestine«: The Einsatzkommando of the Panzer Army Africa, 1942, in: Yad Vashem Studies 35 (2007) issue 1, pp. 1-31; cf. Dan Diner, Ein anderer Krieg. Das jüdische Palästina und der Zweite Weltkrieg 1935–1942, München 2021.

70 The newspaper ceased to exist in April 1943 in large part due to the bombing of the printing house; cf. Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem (fn 12), p. 206.

71 Arendt, Farvos (fn 52).

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.

74 Arendt, Denktagebuch (fn 23), pp. 42-43.

75 Hannah Arendt, Zionism Reconsidered [1944], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 343-374.

76 Arendt, Confusion [14 August 1942], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 170-171.

77 In 1942, in Popular Front Paris’ immediate aftermath, Arendt was still emphatically internationalist and cosmopolitan, enraptured by Rosa Luxemburg’s analysis of imperialism and inclined towards some version of socialism bringing the ›Jewish Question‹ into dialogue with (however cursory) readings of Marx, Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky. See Arendt/Blücher, Briefe 1936–1968 (fn 36); further: Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt (fn 38), pp. 124-125.

78 The ties to the British imperial class are suggested in Viola Alianov-Rautenberg, Kindred Spirits in the Levant? German Jews in British Palestine, in: Israel Studies 26 (2021) issue 3, pp. 122-137, here p. 122.

79 Indeed, Yishuvists and left/labor Zionists agreed, one of the idiosyncratic features of Zionist colonialism in the 1930s and 1940s was that due to the lack of a capable capitalist class it was the labor movement that headed the project of colonization and state formation. See Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies. Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906–1948, Berkeley 1996, pp. 54-56.

80 Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington, New York 1963, p. 149.

81 Last two citations from Arendt, Farvos (fn 52).

82 Hannah Arendt, On Violence, New York 1969, p. 80.

83 Hannah Arendt to Gershom Scholem, 21 April 1946, in: Arendt/Scholem, The Correspondence (fn 31), pp. 47-50, here p. 49.

84 Traverso, The End of Jewish Modernity (fn 32), p. 70.

85 Gil Rubin, From Federalism to Binationalism: Hannah Arendt’s Shifting Zionism, in: Contemporary European History 24 (2015), pp. 393-414; on the extraction of explicitly socialist thought and the tradition of class struggle as part of her ideas on the council system, see James Muldoon, The Origins of Hannah Arendt’s Council System, in: History of Political Thought 37 (2016), pp. 761-789; in another context: pan-African federalism, see Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire. The Rise and Fall of Self-determination, Princeton 2019.

86 Last two citations from Arendt, Farvos (fn 52).

87 Braese, Eine europäische Sprache (fn 45).

88 This is explored in, amongst other works, Clark’s seminal study of the Soviet cultural revolution of the 1930s and its internationalism; see Katerina Clark, Moscow, the Fourth Rome. Stalinism, Cosmopolitanism, and the Evolution of Soviet Culture, 1931–1941, Cambridge 2011.

89 Hannah Arendt, We Refugees [1943], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 264-274, here p. 274.

90 Eynikayt is often translated as Unity. However, the more accurate translation is Unification. This nuance was discussed by the creators of Eynikayt themselves, who envisioned a process of unification behind the common antifascist goal rather than starting from the false presumption of unity. See: Solomon Abramovich Lozovsky, quoted in Shimon Redlich, War, Holocaust and Stalinism. A Documented Study of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR, Luxembourg 1995, Doc. 17.

91 Hannah Arendt, Voz zol vern fun Daytshland?, in: Eynikayt, 15 April 1944, pp. 6-7.

92 Chaim Zhitlovsky, Di oyfgabn fun dem shrayber un kinstler komitet in der itstiker tsayt, in: Yiddishe kultur 7-8 (August 1942), pp. 3-4.

93 On both committees, see Shimon Redlich, Propaganda and Nationalism in Wartime Russia. The Jewish Antifascist Committee in the USSR, 1941–1948, Boulder 1982, pp. 104-107.

94 Hannah Arendt, The Return of Russian Jewry [1942], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 171-176, here p. 172.

95 Arendt, The Return (fn 94), p. 174.

96 Hannah Arendt, The Crisis of Zionism [1943], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 329-337, here p. 336.

97 Cf. Traverso, The End of Jewish Modernity (fn 32), p. 70.

98 Fields/Fields, Racecraft (fn 19).

99 All quotes from Arendt, Voz zol vern fun Daytshland? (fn 91).

100 Zaritt, Taytsh Manifesto (fn 11), p. 191.

101 Arn Tseytlin, Fun fraytog biz fraytog: A bukh vegen Eykhman-protses, in: Der tog/Morgen-zhurnal, 12 November 1965, p. 5; also mentioned in Rokem, Hannah Arendt and Yiddish (fn 52).

102 Jacob Robinson, And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight. The Eichmann Trial, the Jewish Catastrophe, and Hannah Arendt’s Narrative, Philadelphia 1965.

103 On the history of this fateful binary, see Adi Ophir/Ishay Rosen-Zvi, Goy. Israel’s Multiple Others and the Birth of the Gentile, Oxford 2018.

104 Richard I. Cohen, A Generation’s Response to Eichmann in Jerusalem, in: Aschheim, Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem (fn 5), pp. 253-280, here p. 258.

105 Hannah Arendt, »The Formidable Dr. Robinson«: A Reply, in: New York Review of Books, 20 January 1966; reprinted in Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 496-511. Arendt followed the Yiddish discourse around Eichmann in Jerusalem, as she hints at in a letter to the journalist Samuel Grafton; see Hannah Arendt, Answers to Questions submitted by Samuel Grafton [1963], in: Arendt, The Jewish Writings (fn 59), pp. 472-484, here p. 483.

106 She had already explored this structural implication in Nazi crimes in 1945. See Hannah Arendt, Organized Guilt and Universal Responsibility, in: Jewish Frontier 12 (1945), pp. 19-23; in German: Arendt, Organisierte Schuld, in: Die Wandlung 1 (1945/46), pp. 333-344.

107 Hannah Arendt in a letter to Karl Jaspers on 30 June 1947, in: Arendt/Jaspers, Correspondence 1926–1969, ed. by Lotte Köhler and Hans Saner, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber, New York 1992, pp. 90-91.

108 Moyn, Liberalism Against Itself (fn 9), p. 116.

109 Ibid., pp. 115-139.

110 Arendt, On Violence (fn 82), p. 96.

111 Arendt, Denktagebuch (fn 23), pp. 42-43.

![›German Jews have as their mother tongue [muter-shprakh] German‹, Hannah Arendt commented in 1942, ›and when they don’t speak Hebrew, they also don’t switch to Yiddish. And because the German Jews do not speak Yiddish, they get discriminated against as non-Jewish Jews.‹ (excerpt from Hannah Arendt, Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev, in: Morgen-zhurnal, November 1942) ›German Jews have as their mother tongue [muter-shprakh] German‹, Hannah Arendt commented in 1942, ›and when they don’t speak Hebrew, they also don’t switch to Yiddish. And because the German Jews do not speak Yiddish, they get discriminated against as non-Jewish Jews.‹ (excerpt from Hannah Arendt, Farvos daytshe yidn kumt on shver zikh araynpasen in yishev, in: Morgen-zhurnal, November 1942)](/sites/default/files/medien/static/2023-2/Chorley-Schulz_2-23_Abb1.jpg)