Billy Graham in Düsseldorf, June 1954

(Bundesarchiv, Picture 194-0798-41, Photo: Hans Lachmann)

In June 1954, American evangelist Billy Graham came to the Federal Republic of Germany for his first revival meetings. In Frankfurt, he preached at the American Christ Chapel, in Düsseldorf at the Rheinstadium, and two days later he closed his first German campaign with a service at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin. Thousands came to see him and hundreds stepped forward at the end of the service to publicly accept Christ as their Savior. Another campaign fol-lowed in 1955. The American preacher then returned to Germany again during the 1960s, and his work there peaked in 1970 with his EURO 70 campaign.1

Graham’s campaigns in Germany were not foreign spectacles, but rites of passage in German Protestantism. For many actors in the religious field, Graham evoked and catalyzed fear of secularization and hopes for rechristianization. Being an icon of religious modernization and a return to the traditional at the same time, he became a focal point of self-reflection for German Protestants in the 1950s and 1960s. Church leaders, theologians, and laymen used Graham’s campaigns to discuss secular and political challenges and deep social transformations in the religious and secular sphere. Therefore, leading Protestant bishops such as Otto Dibelius and Hanns Lilje supported Graham’s campaigns. They published circulars advertising the so-called crusades and said closing prayers at the events. Influential theologians like Karl Barth, Helmut Thielicke, and Helmut Gollwitzer met Graham and published thoughts on his evangelism, theology, and mission. Their points of view varied between sharp intellectual criticism and well-meaning curiosity. Especially the German free churches gave the transnational, evangelical hero an enthusiastic welcome with publications and local organizational support.

Graham’s mission was characterized on one side by a highly traditional message combining conservative values and a fundamentalist theology and, on the other side, by his modern revival techniques, his use of mass media, and his appearance as an American, suburban, middle-class consumer. When Graham first came to Germany, he was only thirty-six years old and the German press described his good looks, his love for playing golf and walking the dog, and his fashionable and casual style.2 His mission was characterized by air miles, spotlights, and microphones. Yet the preacher’s message stood in sharp contrast to his modern appearance. Graham was a self-defined fundamentalist. He emphasized the literal accuracy of the Bible, he expected the Second Coming of Christ, and he preached the actual existence of heaven and hell. With these themes and particularly with his call to personal conversion at the end of his services, he stood at the fringe of mainstream Protestantism in Germany. Still, Germans came to hear him by the thousands, and they did so for reasons that I will explore in this article.3

Graham’s mission could neither stop declining church membership in Germany nor the process of secularization. His revival meetings, however, trig-gered and influenced German debates on rechristianization as a political process and the modernization and democratization of Protestantism. Hence, they offer an important lens through which to explore politicization and westernization processes in German Protestantism generated by both the Cold War and the rise of consumerism. This approach broadens the perspective of contemporary religious history, which has so far focused closely on church structures and debates in intellectual and theological circles, and traces instead changes in the public discourse on religion and in ordinary West German Protestants’ beliefs and rituals.4 By these means, it complements research on Catholic popular religiosity in the 1950s that has shown the influence of Cold War fears on West German Catholicism.5 It also offers a way to integrate religious history into the historiography of Cold War culture6 and consumption in West Germany,7 hence highlighting the persistent and formative importance of religion in modern societies.

2![]()

1. The West German Protestant Landscape

Graham and German Protestants met at a watershed in the history of German Protestantism. The experience of having failed during the Third Reich that found expression in the 1945 Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt led to a new commitment to democracy and the ideology of the West in Protestant circles.8 This change was accompanied by a stronger engagement with the public and active involvement in political debates, which found its expression in the new Protestant academies and the organization of a regular mass lay meeting called the German Protestant Kirchentag. The new Protestant outreach to laypeople and the deeply felt need to engage in a dialogue with the German public indicated the beginnings of a democratization and politicization process in German Protestantism.9

Inevitably, German Protestantism was drawn into public and intellectual debates about the rechristianization of Germany to fight and hopefully reverse secularization tendencies. Rechristianization described the rearrangement of the European value system based on the imagined framework of the Christian Occident. Religious belief was supposed to immunize the German public against the atheist, communist threat, in particular, and secular, totalitarian cravings in general. Church historian Martin Greschat has pointed out that rechristianization was not just a religious campaign, but had a deeper political meaning in spreading traditional, conservative civic values.10 That is one of the reasons why the American occupying forces had stimulated and supported the rechristianization discourses in West Germany after the war. From their perspective, rechristianization was part of their reeducation campaign that aimed at the westernization and democratization of the country.11

3![]()

The campaign to lead German society back to its religious roots triggered discussion in Protestant circles about how to reach out to the public at large. At the beginning of the 1950s, this debate focused on the search for new methods to communicate faith. A Protestant pamphlet pointed out that such methods could include the use of broadcasts, movies, theaters, and journals. The publication stated that missionary work in Germany was in need of a ‘new look’.12 Leading Protestant figures like the Hanoveranian State Bishop Hanns Lilje called in particular for a new relationship between the churches and media. In the long run, the call for the churches’ stronger engagement with the public fundamentally transformed and modernized them.13

The outreach for new church members was not just motivated by the political atmosphere of rechristianization, however, but also by the receding religious revival that had swept over Germany after the Second World War. The numbers spoke for themselves: in 1949, 43,000 people joined the Protestant church, yet the number of Germans leaving the organized church at the same time was twice as high.14 These facts indicated as much a need for religion as they showed disappointment with the traditional church structures on hand to fill this need. That is why leading German Protestants began to search not just for new ways to gain members, but also for a transformation of church life to retain them. Volksmission, the mission among the German people, became the catchword of these days.

This was the religious landscape that Graham entered when he first came to Germany in 1954. His campaigns there were successful, because they provided a space in which to display and experience abstract hopes for modernization in the religious realm and subtle fears of secularization. The American preacher seemed to fulfill the promise of rechristianization in Europe, and he used the modern revival techniques that German Protestantism so desperately needed. Moreover, Germans embraced the political subtext of Graham’s campaigns, which mixed religious emotions and anti-communist manifestations produced by U.S. Cold War culture. Participation in the crusades helped many Germans find their place in the imagined community of the Free World. Finally, Graham’s mission helped German Protestants come to terms with the Americanization of their lifestyle. Graham’s obvious middle-class lifestyle and his open glorification of communications and sales techniques bridged the gap between the traditional ascetic Protestant milieu and the alluring consumer and popular culture of the 1950s.

4![]()

2. Challenging German Protestantism

In 1953, the president of the German Conference of Evangelists (Deutsche Evangelistenkonferenz), Wilhelm Brauer, had become aware of Billy Graham’s worldwide mission at a conference in Clarens, Switzerland. In cooperation with the German Evangelical Alliance, the leading German federation of evangelical Christianity, Brauer invited Graham to come to Germany.15 After first visiting American troops and holding a service at Christ Chapel in Frankfurt on 23 June, the American evangelist arranged two revival meetings for German Christians, one in Düsseldorf on 25 June and another in Berlin on 27 June. Both crusades followed the same course and were no different from the revival meetings that Graham had held before in cities such as London, Amsterdam, Stockholm, and Albuquerque. A choir of 1,300 voices, all members of the West German Young Men’s Christian Association, opened the event singing traditional German Protestant hymns. Afterwards, 200 young German Christians played trombones. Wilhelm Brauer officially opened the event emphasizing that the Gospel is the same in the United States, Europe, and Germany. After that, Beverley Shea, Graham’s musical manager, and his wife, Ruth, performed evangelical hymns and added some American flavor to the event. Finally, Billy Graham appeared and preached for 40 minutes on the story of the rich young man in the Gospel of Mark, Chapter 10. A German theology student translated the sermon sentence for sentence, and Graham ended with a call to the audience to come forward and accept Christ as their Savior.16

Billy Graham’s Audience in Düsseldorf, June 1954

(Bundesarchiv, Picture 194-0798-24, Photo: Hans Lachmann)

Graham was enthusiastically welcomed by German Christians. When he first preached at the Christ Chapel, 2,000 Germans listened to the service that was transmitted via speakers to a nearby parking lot. The organizing committee for his Düsseldorf campaign, headed by the German evangelical Paul Deitenbeck, had to change the venue from the ice rink to the significantly larger Rheinstadium, where 25,000 people attended Graham’s service. In the audience, one could find students and professors from prestigious theological departments at the Universities of Münster, Bonn, and Marburg; members of evangelical schools, missionary seminars, and church colleges (Kirchliche Hochschulen); as well as ministers, evangelists, and laymen. Interested people travelled in busses from places as far away as Flensburg and Hannover. Two days later, another 80,000 Germans gathered at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin.

It was one of Graham’s campaign rules that he preach only on invitation and with the backing of local churches and congregations. Protestant church officials demonstrated their support by attending the revival meetings and tak-ing their seats on the stage next to the American guest. Church Superintendent Heinrich Held, the head of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland, said the closing prayer in Düsseldorf before the audience jointly said the Lord’s Prayer. When Graham returned to the area for a one-day campaign in Dortmund in 1955, Superintendent Bachmann from the Evangelical Church of Westphalia emphasized at a press conference the church’s support for Graham. More importantly, the American preacher enjoyed the support of two influential fig-ures in German Protestantism, Bishop of Berlin-Brandenburg Otto Dibelius and Bishop of Hanover Hanns Lilje. The reasons for their support provide insight into the hopes and fears with which the German Protestant churches struggled in the mid-1950s.

5![]()

Dibelius shared a deep concern with Graham about secularization, a process that he understood as the final triumph of materialism, scientism, and state politics over Christian ethics. Graham’s preaching at the Olympic Stadium on the failure of materialism and rationalism was music to the bishop’s ears. He also shared Graham’s conviction that the atomic bomb and its use was the genuine expression of the secular age that had already found its cruelest manifestation in National Socialism.17 Apart from that, Dibelius was driven by a deep commitment to mission within German society. He constantly aired his grievances about the rigid and stifled nature of Protestant church life in Berlin. Instead he dreamed of a new, dynamic community life, for which he saw the American religious landscape as a shining example. The bishop’s openness to other religious forms and missionary approaches was a byproduct of his engagement in the global ecumenical movement. He made this insistently clear when he published a circular to the ministers of the Protestant churches in Berlin to encourage their support for Graham’s campaign there in 1960. In the age of ecumenism, he stated, Berliners’ hearts had to be open to approaches coming from other countries and churches.18

Like Dibelius, Lilje also supported Graham out of a deep concern about secularization, an earnest desire for popular conversion, and an admiration for ecumenism in general and the American religious landscape in particular.19 Even though the bishop was a church modernizer when it came to the use of media and public engagement, he also had a soft spot for the German pietistic tradition. From his point of view, pietism stood for deep knowledge of the Bible, the ability of laypeople to understand and interpret the word of God, and the commitment to a personal decision for Christ. He especially admired the honesty of a pietistic Christian lifestyle and the liveliness of pietistic commu-nities. These aspects of Christian life he found under threat by an overly mod-ernized version of theology and faith, a concern entirely shared by Graham.20

Taking up contemporary notions of a Western European community of values, Lilje was especially committed to the ideal of the Christian Occident and the vision of a European community based on the principles of Christian traditions and Christian citizenship. This vision was influenced not only by his deep admiration for the American Christian landscape, but also by his unconditional trust in rechristianization. Therefore, the Hanoveranian bishop supported Graham in several ways. From the 1950s on, he publicly praised the campaigns. In 1960, he joined the organizing committee for Graham’s German campaign and took a seat next to him on stage during the Berlin crusade that same year.21

6![]()

The church’s support was an important gain for Graham; however, he owed his public breakthrough to the German press. Many journalists attended the crusades and were remarkably welcoming towards the American preacher, even though his modern methods and preaching techniques seemed as foreign to them as his message and the call to conversion at the end of each service. But prevailing fears of secularization and hopes for rechristianization strongly influenced the press coverage of Graham’s events.

Even the conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung joined the choir of Graham’s disciples. Its reporter, Heddy Neumeister, praised the quietness and sobriety of the crusade held in Frankfurt in 1955. She observed a deep longing in the modern masses to familiarize themselves with the Christian faith in ways that exceeded the traditional Sunday service. Stating that a process of spiritual decline had taken place over the last two centuries, leaving many people unable to relate to traditional religious forms, she now assigned Graham a leading part in the reawakening of spiritual life in Germany.22

Günter Matthes, who commented on the 1954 crusade in Berlin for the daily Tagesspiegel, also gave a mainly favorably account of the event. He was struck by Graham’s preaching style, which combined commitment and sincerity with a refreshing simplicity. Here he saw a possible new way to communicate faith, as was discussed in Protestant circles at the same time. Nevertheless, he was more skeptical about Graham’s ability to reach out to those who stood outside the church. He pointed out that the audience that had gathered at the stadium already came from a Christian background.23

7![]()

Rolf Buttler, sent to Graham’s 1955 campaign in Dortmund by the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, was also taken by Graham’s sincerity. In his article, he reached the conclusion that Graham’s mission was not entertainment but a powerful demonstration of faithful people no different from the Protestant Kirchentage.24 Indeed, the German Protestant Kirchentag, masterminded by Reinhold von Thadden-Trieglaff, also provided a forum for thousands of German Christians to discuss their spiritual needs and political concerns. More than 200,000 Germans had attended the Kirchentag’s closing service at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin in July 1951.25 Buttler’s comparison of the Graham campaign and the Kirchentag showed that the public saw both events as integral aspects of the same process of giving Protestant life in Germany a new look and increased visibility. Protestant Christians shared this opinion, and many who attended Graham’s 1954 crusade in Berlin wore buttons advertising the Kirchentag.

The newspaper coverage of Graham’s crusades was significantly influenced by a general public desire for a more dynamic, modern, and lively approach to religion, which traditional institutions apparently could not offer. Public secularization fears and modernization hopes merged in a call for rechristianiza-tion that Graham’s campaigns appeared to fulfill.

In the 1950s, criticizing Graham was not the rule, but the exception. When critical voices arose, they tended to evoke the German fascist past. In 1955, the general secretary of the Kirchentag, Heinrich Giesen, published a critique of Graham that did not leave any room for interpretation: ‘Wir haben zweimal in Massen ja gesagt, einmal in Langemarck und nach Stalingrad im Sportpalast. Ein so verwundetes Volk wie das deutsche darf nicht der Gefahr des Rausches ausgesetzt werden und muß Zeit finden, damit seine Wunden heilen können.’26 Giesen was strongly influenced by his engagement in the Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche) during the Third Reich, and Graham’s mission reminded him of the worst possible relationship between the masses and their seducer.

In similar fashion in a church newspaper in 1960, the Hamburg minister Hartmut Sierig criticized the mass character of Graham’s events. Noting that the young American evangelist appeared to display admiration for the German nation and its poets, philosophers, and theologians, Sierig warned that Graham’s events could easily be transformed into nationalistic celebrations. To Sierig, Graham had the potential to stir up the kind of nationalism that he wished the Germans had overcome.27 When the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reprinted parts of Sierig’s critique, it caused a storm of protest. Several people who had attended the crusades wrote to the editors defending Graham’s work and praising his clear and sincere message as well as his unique methods.28

8![]()

Another group of voices that were quite concerned about Graham’s mission came from Protestant theologians. Considering the intellectual simplicity of Graham’s fundamentalist faith, it is not surprising that he never established serious contact with the leading German Protestant theologians. Still, many of them attended his press conferences and crusades. For example, a professor of theology at the University of Bonn, Helmut Gollwitzer, attended Graham’s first public meeting in Düsseldorf, even though he missed the crusade later that day. As Gollwitzer later described in a letter to Giesen, his impression of Graham was much more positive than he had initially expected. At the same time, he expressed serious doubts about Graham’s evangelizing efforts really reaching those who stood outside the churches.29

Even though a strong supporter of an engaged mission himself, theologian Helmut Thielicke also initially had strong reservations about Graham. As he later recalled in his memoirs, he had thought for a long time that essential parts of Christian teaching were missing from Graham’s campaigns. His criticism focused particularly on Graham’s individual-centered doctrine of salvation. Nonetheless, Thielicke joined Graham on stage during a crusade in Los Angeles in 1963. Now he was impressed by Graham’s sincerity and modesty, even at the moment when thousands came forward to accept Christ as their Savior. After the event, he asked Graham for his personal opinion on his crusades’ messages and methods. The young preacher answered that he himself had deep concerns about the look and especially the methods of his campaigns, and that he only proceeded as usual because of the obvious need for his methods to spread the Gospel. The critical German theologian was at least impressed by the American fundamentalist’s honesty.30

Karl Barth, one of the leading Protestant theologians of the twentieth century, was also personally acquainted with Graham. He emphasized again and again that he liked him as a person, but he nevertheless expressed strong criticism concerning not just Graham’s methods but above all his message. In an interview given in San Francisco in 1962, the seventy-six-year-old theologian accused the younger preacher of turning the gospel of hope into a message of fear. Barth rejected the idea that existing political or social threats would bring people back to religion. With this critique, he attacked Graham’s constant mis-sionary use of apocalyptic scenarios such as the outbreak of a nuclear war or the worldwide victory of communism. In particular, Barth rejected Graham’s simplistic condemnation of communism. He also resented Graham’s military preaching style, which had earned Graham the nickname ‘God’s machine gun’. The theologian compared Graham’s evangelical style to military command and gun fighting.31 In so doing, he publicly attacked Graham’s dual religious and political role in the Cold War culture of the United States and West Germany.

9![]()

3. Protestant Cold War Culture

Karl Barth’s implicit political critique of Billy Graham’s mission was not plucked out of thin air. Graham’s success in the United States following his first crusade in Los Angeles in 1949 was clearly a byproduct of the Cold War. In times when fears of communist infiltration and the outbreak of the Third World War ran high, religion brought comfort and hope into American households. Like in Germany, church membership climbed to previously unknown highs in the United States following the end of the Second World War.32 At the same time, the boundaries between religious conviction and patriotism blurred. Evangelical preachers defined atheistic communism as a godless religion and called for a rechristianization of the United States to fight the Soviet enemy on spiritual ground. Thus Graham instructed his fellow citizens, ‘If you would be a true patriot, then become a Christian’, and ‘if you would be a loyal American, then become a loyal Christian’.33

The spiritual reawakening that American society experienced in the 1950s was marked by a new political engagement of churches and the transformation of religious commitment into a civic duty. Graham spearheaded this transformation process. During his crusades, he mixed his evangelical message with anti-communist statements and patriotic convictions. Again and again, he evoked the image of the chosen nation, preached to his flock the national mantra ‘In God We Trust’, and celebrated freedom as a spiritual and political value. He involved evangelicals in the political discourse and chose symbols and rituals that transformed his revival meetings into sites of patriotic celebration. In 1952, for example, he preached in Washington, D.C. on the steps of the Capitol, staking out a position at the political center of the United States. The decoration of Madison Square Garden in New York City, where he held a several-months-long crusade in 1957, spread a similar message. The Garden was shrouded in red, white, and blue. American flags hung from the ceiling.34 Among traditional hymns, the hymnal included ‘America the Beautiful’, the country’s unofficial national anthem.

Naturally, Graham did not directly translate these rituals, symbols, and rhetorical patterns to the German context. Nevertheless, Germans also perceived him as a political figure and particularly as a cold warrior. Graham’s first appearance on German soil gave this impression. After a several-weeks-long crusade in London and other European cities, Graham’s plane touched ground at Frankfurt Airport on 23 June 1954. American military personal welcomed the evangelist there and took him to Christ Chapel, where he preached in front of a predominantly American audience. The words that Graham spoke in Frankfurt set the tone for his first German campaign. In his sermon, he called the Germans ‘brothers in arms’ and called for the rearmament of the country, which he saw as the United States’ ally in defending the Free World. The evangelist praised Germany’s reconstruction and its road to economic success; however, he urged West Germans to return to Christian beliefs as a shield against the atheist Bolshevism on the other side of the Iron Curtain. With this message, he translated the intellectual and theological debates about the Christian West for ordinary Germans and helped them to connect to the nebulous image of the Free World. The German press gladly picked up on his rhetoric and the widely circulated Bild-Zeitung came up with a headline that focused on the country’s rearmament as an American ally: ‘Billy Graham predigt Waffenbrüderschaft!’35

10![]()

When Graham continued his campaign in Germany, first in Düsseldorf and later in Berlin, it was already clear that he was not just on a religious mission in Germany. Even though the organizing committees and the preacher himself constantly emphasized the religious core of his work, the German press embedded his crusades into the discourse on the Cold War. This tendency was especially evident when he preached in Berlin. On the day before his revival meeting in the Olympic Stadium, the Berlin tabloid B.Z. explained why Graham was coming to the city: ‘Weil in Berlin das Herz der Welt schlägt, weil von hier aus – mehr als von jedem anderen Platz der Welt – der Angst die Stirn geboten wird, deshalb spricht Billy Graham in Berlin.’36 With these words, the paper placed the American preacher and his campaign in the middle of a political discourse that declared Berlin the center of the Free World. The organizing committee of the campaign joined in. Presiding church official Theodor Wenzel published an article in a special issue of the church paper Sonntagsblatt that started with a description of Berlin’s difficult situation. He declared the city a symbol of the divided world. In expressing his hope that Graham would erect the cross in a divided world, he linked political and religious discourses.37 When Graham preached at the Olympic Stadium, he opened his sermon with these words: ‘Millionen von Christen in der ganzen Welt wissen um die besondere Lage Berlins. Für Berlin wird in der Welt mehr gebetet als für jede andere Stadt, und die Berliner sind nicht vergessen.’38

Leading political and cultural figures took their seats on the dignitary grandstand. The mayor of Berlin, Walther Schreiber, sat next to the president of the Berlin police, Johannes Stumm, and a federal minister, Robert Tillmanns, who was also the chairman of the Protestant study group in the Christian Democratic Party. Bishop Dibelius represented the official Protestant church and said the closing prayer before 80,000 joined to sing the final hymn, ‘Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott’.39 With this Lutheran battle cry, they all closed ranks with the prophet who had come to Berlin to rechristianize Germany in defense of the Free World.

Graham’s next Berlin crusade, in 1960, was transformed even further into a political event. Many different people played their part. The organizing committee of Graham’s campaign, represented by Paul Schmidt and Max Kludas, approached the mayor of Berlin asking for financial support. They pointed out that the special situation of the divided city made additional fundraising necessary. To accommodate visitors from the eastern part of the city, the organizing committee had decided to construct a tent on the Platz der Republik with 20,000 seats. Since the visitors of the East could not contribute to the increased financial burden, the organizing committee asked the Bureau for the Affairs of Greater Berlin to step in.40 This bureau indeed sponsored the campaign with 10,000 DM; even the Federal Ministry for inner-German Affairs contributed another 20,000 DM.41 These amounts highlight the political importance that was assigned to Graham’s campaign in Berlin.

11![]()

The organizing committee emphasized that only the special local circumstances in the divided city had made the construction of the tent necessary. The tent was supposed to be in easy reach for the thousands of visitors who had to cross the sector border into the western part of the city. Apart from that, the tent was undeniably a strong political symbol with its location right behind the Brandenburg Gate. That became evident when the East Berlin propaganda offensive against the tent set in. In an internal memorandum, the East German secretary for church affairs lamented that the tent was an attempt to infiltrate the East German population with ‘politischem Klerikalismus’.42 The mayor of East Berlin Waldemar Schmidt officially requested that West Berlin mayor Willy Brandt tear it down. The speaker of the Berlin Senate rejected this interference in the internal affairs of West Berlin and shot back that Billy Graham could preach in Berlin as often and as long as he wished.43

Obviously, Graham’s campaign in Berlin enjoyed the public support of several political institutions. The West German press fueled the explosive political atmosphere by reprinting several propaganda articles from the East German press. This attempt to expose and ridicule the communists’ fear of the American preacher increased Graham’s credentials as a cold warrior. The fact that American TV channels covered parts of the crusade for their audiences back home emphasized as well that Graham’s second Berlin crusade was special. It was Graham’s visit to the most important outpost of the Free World.

Still, it was not just the German press that bridged the religious and political realms. Even voices from the evangelical organizing committee joined the political sirens surrounding Graham. Peter Schneider, Graham’s interpreter and general secretary of the organizing committee, sent out a press release after the Berlin crusade in which he called the East German propaganda against Graham an expression of the atheistic emptiness of the East. In addition, he implored the political leaders of the Western world to take the Christian faith seriously when addressing the prevailing problems of the world.44 Now the evangelical organizers had closed ranks with the advocates and intellectual pioneers of the rechristianization debate.

12![]()

The fact that the German audiences had perceived Graham not just as a religious, but also as a political figure, backfired when he returned to Berlin in 1966. By then, the Vietnam War was challenging the transnational consensus of the Free World. Former crusades had not left any doubt about which side Graham had picked in the worldwide struggle between communism and capitalism. His anti-communism was well known, and his support for the American military had been obvious since he had preached to the troops in Korea on Christmas Day in 1951. In 1966, he would repeat this gesture with a visit to Vietnam.45

German Protestants and the German public in general had a significantly more critical attitude towards the American military action in Southeast Asia. Therefore, as early as 1965, when General Superintendent Hans-Martin Helbich invited all members of the Protestant church in West Berlin and members of the German free churches to an initial informational meeting about Graham’s next campaign in Germany, he outlined his awareness that Graham’s political activities had stirred concerns in German churches.46 The German press had also changed its attitude towards the American preacher. When Graham finally arrived in Berlin in 1966 and repeated his conviction that Berlin was the most important strategic point of the world, the German press reacted less enthusiastically than it had a decade earlier.

Graham’s political rhetoric and aura of military precision, which had comforted Germans in the 1950s, now stirred protest. The one who had been welcomed in Germany as another American savior was now perceived as a threat. The left-leaning Frankfurter Rundschau described Graham’s 1966 campaign in Berlin in military terms. One article, headlined ‘Graham “befeuert” Berlin’ pointed out that his campaign was organized with military accuracy. The author declared Graham’s problematic stance on the Vietnam War to be the reason behind the limited turnout at his recent campaign in London.47

Graham’s Berlin campaign in 1966 marked the end of a particular interaction between American evangelism and German Protestantism at a time when discrepancies in theology and methods of evangelism had been obscured by an overshadowing political consensus. Graham came not just as a religious missionary to Germany, but as an ambassador of the Free World. His crusades were as much orchestrations of the imagined community of the West as they were revival meetings. While church officials, theologians, and politicians discussed the importance and meaning of Christian faith in the Free World, it was during Graham’s campaigns that ordinary Germans came to know and experience the political meaning of Christian faith in the Cold War order. Their religious and political needs were fulfilled at the same time.

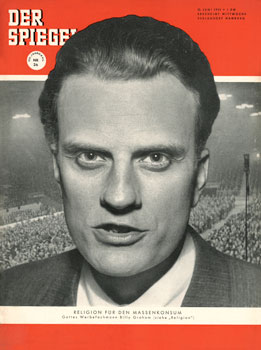

A characteristic portrait of Billy Graham, April 1966

(Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-03261, Photo: Warren K. Leffler)

13![]()

4. Engaging with Protestant Consumers

The westernization of German Protestants was not limited to their political attitudes and values, including the development of a stern commitment to the Free World.48 It was also reflected in their embrace of the consumerism that bound them to the United States just as much as it set them apart from the socialist countermodel practiced in the GDR. The culture of consumption, however, significantly altered how people expressed their beliefs and searched for spiritual fulfillment. With an increasing number of consumer goods, with advertising and marketing on the rise, personal choice also became more important in the religious field. At the same time, religious rituals and beliefs became consumable; they were stripped of hard-to-follow traditions and dogmatic burdens and turned into a spiritual commodity that was easy to purchase.49 The reconciliation of consumerism and religious life is a significant example of how religion adapted to its changing societal surroundings in the 1950s. It is one of the consequences of the process that sociologist Helmut Schelsky described as the adaptation of faith to modernity’s form of consciousness.50

In times of increasing economic prosperity in Germany, and with the breakthrough of consumerism on the horizon, Billy Graham’s crusades provided the first opportunity for popular interaction with a new form of Protestantism that used modern marketing and media techniques and had exactly the ‘new look’ that German Protestantism desperately sought. The reactions towards his campaigns therefore indicated whether or not German Christians were indeed ready for a modernized version of Protestantism.

14![]()

Graham challenged German Protestants from the beginning by openly using modern sales techniques. In a world of increasing consumer choices, Graham knew how to promote and sell his product. His biographer, William Martin, has given several examples of the expressions and gestures that Graham – a former Fuller brushes’ salesman – used to sell his religion.51 Indeed, Graham’s language transformed religious belief into a commodity. The preacher himself famously stated in a Time magazine interview in 1954, ‘I am selling […] the greatest product in the world; why shouldn’t it be promoted as well as soap?’52 When Graham gave his first press conference in Düsseldorf on the day of his crusade there, he used the same image. Therefore, from the beginning, the German press described Graham’s religious mission in terms of production, marketing, and sales. Graham was dubbed ‘Kreuzritter im flotten Zweireiher’, ‘Werbefachmann Gottes’, and ‘Fließband-Evangelist’.53

Many articles pointed out that Graham’s mission revolved around the production and categorization of believers, a process that went even further in westernizing German faith. The press approved of Graham’s methods, its coverage replete with positive images of mobility and technical progress. A reporter from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung described Graham as the modern evangelist who made use of spotlights and microphones and travelled by plane between cities, countries, and continents.54 The German press described his lifestyle, including his passion for golf, and printed pictures of his fashionable wife, Ruth. The preacher was portrayed as the ‘modern apostle’, good looking, tall, slender, and well-dressed. Fashion, style, and religion blended together in the German press coverage of the crusades. This trend was even supported by church officials. When a journalist asked Hanns Lilje about Graham’s stylish appearance, the bishop countered with a question, asking why those who preached the Gospel should not wear decent clothes?55

Graham embodied the idea that religiosity and a generous 1950s consumer lifestyle were compatible. At a time when German Christians’ kitchen appliances were changing as quickly as their travel culture, Graham reconciled their faith with the new world of consumption. His commitment to consumerism, however, reflected strongly on his message and the core of his Christian beliefs. Even though he superficially condemned the failings of materialistic culture time and again, he never sincerely called for social change, as many of his critics have pointed out.56 More than that, with his open commitment to the so-called American way of life, he legitimized the existing capitalist order and Cold War divide. West Germans’ embrace of American consumerism undeniably formed a part of their identification with the West. In this sense, consumption had important political and cultural connotations. Graham’s commitment to consumption reinforced the political dimension of his campaign.57

15![]()

The consumerist aspects of Graham’s modern mission were not just criticized in conservative church circles, but also by left-wing intellectuals. Their criticism blended anti-American stereotypes, a Frankfurt School-inspired social critique, and a quite conservative view on the look and feel of Christian faith and mission. The journalist Barbara Klie, for example, published a sharp critique on Graham in the Süddeutsche Zeitung after she attended Graham’s campaign meeting in Stuttgart in 1955. Klie described Graham’s preaching style and particularly his language in terms of sales and accounting. In addition, she complained that Graham’s language transformed a holy object into a commodity, forcing religion into the straitjacket of modern man’s everyday business concerns. For Klie, the evangelist was a broker and promoter. She complained that his preaching transformed the relationship between God and the human being into a mere business relationship: ‘Die Gnadenverheißung wird als einfacher Geschäftsakt erklärt: “Gott sagt: Ich habe meinen Sohn her-gegeben, gib du deine Sünden her. Dann werde ich dir vergeben.”’58 The journalist stated that the simplicity of Graham’s language depleted the message. Indeed, she averred that Graham’s methods ultimately had detached themselves from their original missionary purpose, developing their own meanings instead. She asked whether the individual participants really came to the events to create a religious community or if they were just in search of general social bonding.

The weekly news magazine Der Spiegel placed Graham on its cover in 1954 with the headline ‘Religion für den Massenkonsum’. The accompanying article took Graham’s sales metaphor to its logical extreme. It compared the moment when the preacher called on his audience members to leave their seats to come forward and accept Christ as their Savior with the culmination of a sales event. The same article compared accepting Christ to purchasing a kitchen knife and signing the sales agreement for a washing machine.59 Without a doubt, the Spiegel’s sharp words had a blasphemous subtext, and the heat of the argument revealed a strong current of anti-Americanism as well as a general critique of consumerism. Yet between the lines, the secular journal defended its own vision of pure, traditional faith against American influence. In so doing, the magazine had joined forces with the most conservative voices in German Protestantism, who indeed saw Graham’s mission as the final abandonment of genuine religious values.

While these critiques undoubtedly had some justification, they only told part of the story. Many people who went to the crusades experienced them as religious services, in some cases even as personally transformative moments. For German Christians, the crusades were the training ground for a Protestantism that combined traditional and modern rituals as well as religious values and consumerism. Some of the crusade participants grabbed their pens afterwards and wrote to newspapers, church papers, and their ministers to defend Graham’s work. These letters characterized the crusades as rites of passage. Their authors often began by expressing an initial uneasiness with the secular staging of the campaign. They displayed bewilderment at the commercial aspects of the event, which resembled the sale of Coca Cola and sausages. Unfamiliar faces in the audience, including giggling girls in miniskirts, also seemed out of place. Nonetheless, many of these letters closed with the observation that ‘the Holy Ghost was in attendance’.60 This trend showed that Graham was able to bridge the secular and sacred for many. He might have arrived as a cold warrior and salesman, but he was still an effective preacher.

16![]()

Billy Graham’s German crusades offer insight into the multilayered interplay of religion and politics in West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s. Moreover, they highlight the transnational dimension of the transformation of religion in the second half of the twentieth century. Fearing secularization, Protestantism in both Europe and the United States adapted to modernization processes as it confronted the challenges of Cold War culture, consumerism, and the rise of television. Therefore, Graham did not provoke a cultural clash in Germany, but was welcomed as a knight in shining armor in a shared battle against secularization. His campaigns were expressions of a common Western religious culture that bridged the Atlantic in the field of religion in the second half of the twentieth century.

Graham’s crusades offer access to West German religious life outside formal church structures. His audiences expressed a unique longing for a more modern spirituality. They lived a dynamic religiosity that has long gone unrecognized in the meta-narrative of secularization in Europe. Graham helped West German Protestants find their place in a transforming society and a new world order. By bridging the gap between the secular and the sacred in his rhetoric and performances, he offered a brand of spirituality that fulfilled religious, political, and consumer needs at the same time.

Furthermore, Graham familiarized West Germans with continuous innovations in media-based revival techniques, thereby helping a modern, media-friendly worship culture to take root in the European religious landscape. That became most obvious when he returned to Germany in 1970 for a week-long revival campaign that transmitted his evening services in Dortmund live via satellite to screens in thirty-six European cities. Again, Germans came in the tens of thousands to see the preacher who for two decades had been showing them that religiosity and modernity were indeed compatible.

17![]()

List of Archives

BGCA: Billy Graham Center Archives

ELAB: Evangelisches Landeskirchliches Archiv in Berlin

EZA: Evangelisches Zentralarchiv in Berlin

LAB: Landesarchiv Berlin

1 On Graham and his mission in general, see David Aikman, Billy Graham. His Life and Influence, Nashville 2007; William Martin, A Prophet with Honor. The Billy Graham Story, New York 1991. Publications on Graham in German are rather rare; see Uta Andrea Balbier, Billy Grahams Crusades der 1950er Jahre. Zur Genese einer neuen Religiosität zwischen medialer Vermarktung und nationaler Selbstvergewisserung, in: Frank Bösch/Lucian Hölscher (eds), Kirchen – Medien – Öffentlichkeit. Transformationen kirchlicher Selbst- und Fremddeutungen seit 1945, Göttingen 2009, pp. 66-88.

2 Millionen Menschen hören Billy Graham, in: General Anzeiger Oberhausen, 25 June 1954. Billy Graham Center Archives (BGCA), Magazine and Newspaper Clippings Collection CN 360, Reel 8.

3 I want to express my gratitude to the editors of this issue for their helpful and thoughtful comments and to my editor, Mark Stoneman, for his careful work and challenging remarks. This essay is based on an annual lecture given at the BGCA in fall 2009. I am deeply grateful to the audience for their comments, which have remarkably improved this essay, and to the staff of the BGCA for their friendly and ongoing support. And I am, as always, tremendously grateful to Jan Palmowski.

4 Martin Greschat, Protestantismus im Kalten Krieg. Kirche, Politik und Gesellschaft im geteilten Deutschland 1945–1963, Paderborn 2010, and Thomas Sauer, Westorientierung im deutschen Protestantismus? Vorstellungen und Tätigkeiten des Kronberger Kreises, Munich 1999.

5 Most recently: Michael E. O’Sullivan, West German Miracles. Catholic Mystics, Church Hierarchy, and Postwar Popular Culture, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 6 (2009), pp. 11-34.

6 An example for a cultural history of the Cold War in Germany is Andreas W. Daum, Kennedy in Berlin, New York 2008.

7 The relationship between religion and consumerism has been broadly researched from a historical perspective for the American case; see Laurence Moore, Selling God. American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture, New York 1994. The impact of consumption patterns on the formation of the German religious landscape has been ignored so far by religious historians. In addition, religion rarely plays a role in works on the history of consumption in Germany; see Heinz-Gerhard Haupt/Claudius Torp (eds), Die Konsumgesellschaft in Deutschland 1890–1990. Ein Handbuch, Frankfurt a.M. 2009.

8 On this difficult period in German Protestantism, see Martin Greschat, Die evangelische Christenheit und die deutsche Geschichte nach 1945. Weichenstellungen in der Nachkriegszeit, Stuttgart 2002.

9 This point is emphasized in Benjamin Pearson, The Pluralization of Protestant Politics. Public Responsibility, Rearmament, and Division at the 1950s Kirchentage, in: Central European History 43 (2010), pp. 270-300. See also Dirk Palm, ‘Wir sind doch Brüder!’ Der evangelische Kirchentag und die deutsche Frage 1949–1961, Göttingen 2002.

10 Martin Greschat, ‘Rechristianisierung’ und ‘Säkularisierung’. Anmerkungen zu einem europäischen interkonfessionellen Interpretationsmodell, in: Jochen-Christoph Kaiser/Anselm Doering-Manteuffel (eds), Christentum und politische Verantwortung. Kirchen im Nachkriegsdeutschland, Stuttgart 1990, pp. 1-24.

11 Axel Schildt, Zwischen Abendland und Amerika. Studien zur westdeutschen Ideenlandschaft der 50er Jahre, Munich 1999. On the Westernization of German political values, see Michael Hochgeschwender, Freiheit in der Offensive? Der Kongress für kulturelle Freiheit und die Deutschen, Munich 1998.

12 Schildt, Abendland und Amerika (fn. 11), p. 113. Cited in Waldemar Wilken, Predigt auf den Dächern, Stuttgart 1953, p. 6.

13 See the contributions in: Bösch/Hölscher, Kirchen – Medien – Öffentlichkeit (fn. 1).

14 Greschat, Die evangelische Christenheit (fn. 8), p. 71.

15 Fritz Laubach, Aufbruch der Evangelikalen, Wuppertal 1972, pp. 83-84. On the history of the German evangelical movement, see also Friedhelm Jung, Die deutsche Evangelikale Bewegung. Grundlinien ihrer Geschichte und Theologie, 3rd ed. Bonn 2001; Siegfried Hermle, Die Evangelikalen als Gegenbewegung, in: Siegfried Hermle/Claudia Lepp/Harry Oelke (eds), Umbrüche. Der deutsche Protestantismus und die sozialen Bewegungen in den 1960er und 70er Jahren, Göttingen 2007, pp. 325-352.

16 50.000 kamen, um Billy Graham sprechen zu hören, in: Westdeutsche Rundschau, 25 June 1954. BGCA, Magazine and Newspaper Clippings Collection CN 360, Reel 8.

17 For Dibelius’ mindset, see Robert Stupperich, Otto Dibelius. Ein evangelischer Bischof im Um-bruch der Zeiten, Göttingen 1989. On secularization and the atomic bomb, see p. 364.

18 Dibelius to the ministers of Berlin, circular, 9 April 1960. Landesarchiv Berlin (LAB), B 002/1765.

19 Hanns Lilje, Memorabilia. Schwerpunkte eines Lebens, Nürnberg 1973.

20 Ibid., pp. 53 and 195.

21 Täglich 20.000 Menschen bei Billy Graham, in: Welt, 29 September 1960, p. 8.

22 Das Nüchterne, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 24 June 1955, p. 2.

23 Ein Missionar unter Christen, in: Tagesspiegel, supplement, 29 June 1954, p. 4.

24 Wir wollen keine Schau bieten, in: Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 29 June 1955, p. 3.

25 Palm, ‘Wir sind doch Brüder!’ (fn. 9), p. 130.

26 ‘We twice affirmed with one voice – once in Langemarck and once [after Goebbels’ speech] in the Sports palace following Stalingrad. A people that has been as wounded as the Germans must not be subjected to the temptation of intoxication and must find time for its wounds to be healed.’ Umstrittener Graham, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 July 1955.

27 Der Feldprediger aus der Neuen Welt, in: Kirche in Hamburg, September 1960. Evangelisches Zentralarchiv in Berlin (EZA), 71/1827.

28 Briefe an die Herausgeber, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 5 October 1960, p. 8.

29 Gollwitzer to Giesen, 7 November 1955. EZA, 71/1827.

30 Helmut Thielicke, Auf Kanzel und Katheder. Aufzeichnungen aus Arbeit und Leben, Hamburg 1965, pp. 200-201.

31 Barth on Graham at a press conference held in Chicago on 19 April 1962, and in a meeting with Methodist ministers on 16 May 1961. See <...> [editor's note: URL no longer retrievable].

32 On the U.S. religious landscape in the 1950s, see Andrew S. Finstuen, Original Sin and Everyday Protestants. The Theology of Reinhold Niebuhr, Billy Graham, and Paul Tillich in An Age of Anxiety, Chapel Hill 2009; Robert Wuthnow, After Heaven. Spirituality in America since the 1950s, Berkeley 1998; Joel A. Carpenter, Revive Us Again. The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism, Oxford 1997.

33 Quote in Stephen J. Whitfield, The Culture of the Cold War, Baltimore 1991, p. 87.

34 Curtis Mitchell, God in the Garden. The Amazing Story of Billy Graham’s First New York Crusade [1957], Charlotte 2005.

35 Bild, 24 June 1954. BGCA, Magazine and Newspaper Clippings Collection CN 360, Reel 8.

36 ‘Because the heart of the world beats in Berlin, because it is here – more than anywhere else in the world – that people stand up against world angst, that is why Billy Graham preaches in Berlin.’ Ein Mann gegen die große Weltangst, in: B.Z., 26 June 1954. BGCA, Magazine and Newspaper Clippings Collection CN 360, Reel 8.

37 Berliner Sonntagsblatt Die Kirche, special edition, 27 June 1954, p. 2. Copy held at Oncken Archive.

38 ‘Millions of Christians around the world know the special situation of Berlin. Berlin is the most prayed for city on earth and the Berliners are not forgotten.’ Pressestelle der evangelischen Kirchenleitung Berlin-Brandenburg, 28 June 1954, cited from the newspaper Der Tag. Evangelisches Landeskirchliches Archiv in Berlin (ELAB), 190. For the role of Berlin in Cold War discourse see Daum, Kennedy in Berlin (fn. 6). As a short audiovisual impression of Graham’s sermon at the Olympic Stadium see <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OJI3EbdevD4>.

39 Ein Missionar unter Christen (fn. 23).

40 Paul Schmidt to Mayor of Berlin, 1 July 1960. LAB, B 002/1765.

41 Note for Major Amrehn, Großstadt-Evangelisation mit Billy Graham/Zuwendungsantrag der Deutschen Evangelischen Allianz, 9 August 1960. LAB, B 002/1765.

42 Staatssekretär für Kirchenfragen an den Magistrat von Groß-Berlin, betr.: NATO-Veranstaltung mit Billy Graham vom 26.9. bis 2.10.1960 in Westberlin. Stadtarchiv Berlin, C Rep. 104-678.

43 SED beschwert sich über Graham, in: Frankfurter Rundschau, 29 September 1960, p. 2.

44 Peter Schneider, Presseinformation, October 1960, p. 3. ELAB, 190.

45 For Graham’s position on the Vietnam War see Martin, Prophet (fn. 1), pp. 343-348.

46 General superintendent of Berlin to all ministers, curates, vicars in West Berlin and all officials of the free churches and the communities in the regional church, 29 December 1965. ELAB, 190.

47 Billy Graham ‘befeuert’ Berlin, in: Frankfurter Rundschau, 19 October 1966.

48 Sauer, Westorientierung (fn. 4).

49 Vincent J. Miller, Consuming Religion. Christian Faith and Practice in a Consumer Culture, New York 2004. The adaptability of his concept in the European context is discussed in: Consuming Religion in Europe? Christian Faith Challenged by Consumer Culture, ed. by Lieven Boeve, Special Issue of Bulletin ET [= European Society for Catholic Theology] 17 (2006).

50 Helmut Schelsky, Ist die Dauerreflexion institutionalisierbar? Zum Thema einer modernen Religionssoziologie, in: Zeitschrift für evangelische Ethik 1 (1957), pp. 153-174. Such an adaptation process is marvelously described in: Benjamin Ziemann, Katholische Kirche und Sozialwissenschaften 1945–1975, Göttingen 2007.

51 Martin, Prophet (fn. 1).

52 Time magazine, 25 October 1954, p. 8.

53 Kreuzritter im flotten Zweireiher, in: Ruhr-Nachrichten, 24 June 1954; Ein Werbefachmann Gottes, in: Westdeutsche Zeitung, 25 June 1954; 40.000 Menschen hören Billy Graham im Stadion, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 22 June 1955. BGCA, Magazine and Newspaper Clippings Collection CN 360, Reel 8.

54 Mit Bibel, Mikrophon und Cowboyhut, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 April 1954, p. 2.

55 Zwölf Ernten im Jahr, in: Spiegel, 23 June 1954, pp. 21-26 (p. 26).

56 That is the dominant verdict in Michael Long (ed.), The Legacy of Billy Graham. Critical Reflections on America’s Greatest Evangelist, Westminster 2008.

57 This argument derives from the methodological framework developed, for example, by Erica Carter, How German is She? Postwar West German Reconstruction and the Consuming Woman, Ann Arbor 1997.

58 ‘The doctrine of grace is turned into a business transaction: “God says: I gave my son for you, now give up your sins and you’ll be forgiven.”’ Der Prediger auf dem Fußballplatz, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 4 June 1955, p. 35.

59 Zwölf Ernten im Jahr (fn. 55), p. 23.

60 Some of these letters can be found in: EZA, 71/1827. Quote from Maria Redemaker to Heinrich Giesen, 22 August 1955.