Tom Scott-Smith is Associate Professor of Refugee Studies and Forced Migration, Fellow of St. Cross College Oxford, and Course Director for the MSc in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies. Previously, he worked as a development practitioner concerned with the education sector in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa.1 The following interview discusses arguments and questions arising from his newest book (2020), historical and currents trends of hunger relief, important players, institutions and gender relations in the humanitarian sector – and more. It was conducted by Heike Wieters (Historical European Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) and Tatjana Tönsmeyer (Contemporary History, Bergische Universität Wuppertal) in a back-and-forth conversation via E-Mail.

Your book On an Empty Stomach. Two Hundred Years of Hunger Relief came out with Cornell University Press in 2020 and has received quite some publicity2 – and rightfully so. We both read it with great interest and gain. And while we both do research in a neighboring field and do of course ›get‹ why you decided to work on the topic of hunger and hunger relief, we still want to start this interview by asking about your specific motivation to choose the topic and to enquire about the central questions (and answers) that structure your research.

Your book On an Empty Stomach. Two Hundred Years of Hunger Relief came out with Cornell University Press in 2020 and has received quite some publicity2 – and rightfully so. We both read it with great interest and gain. And while we both do research in a neighboring field and do of course ›get‹ why you decided to work on the topic of hunger and hunger relief, we still want to start this interview by asking about your specific motivation to choose the topic and to enquire about the central questions (and answers) that structure your research.

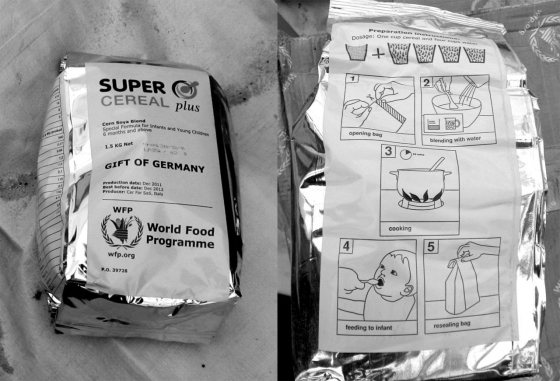

I had the idea for this book when doing research in South Sudan, when I realized how little humanitarian nutritionists knew about the history of their field. As I explained in the book’s preface, I had been studying the daily lives of aid workers, focusing particularly on their technical practices in areas such as nutrition, and I wanted to know where these procedures originated. Rather than beginning with history, it was, in many ways, a classic anthropological starting point – looking askance at the world and trying to understand why people do what they do. From an ethnographer’s perspective, there was so much that seemed unusual in the rituals of aid workers. There were these procedures where they lined children up and measured their arms, referring them to different feeding schemes. There were these unusual foods they distributed, such as Corn Soy Blend, which people would not usually eat. There were these handbooks and systems for sorting people into new groups and categories, assessing them with specifically designed tools. I was eager to learn how this arrangement came to be. The research questions were relatively simple: I wanted to know why aid workers took particular approaches to humanitarian feeding and how things had been different in the past.

When I asked around, it seemed that most aid workers did not know very much about the background to their procedures and systems. In many ways, this is understandable. Aid workers are often young; the field has high rates of burnout as people become exhausted due to insecure contracts and regular movement. This leads to rapid turnover of staff. Aid institutions are also running from crisis to crisis and they are focused on raising funds, so archiving and maintaining institutional memory is rarely a priority.

As a result, I began by asking some older and more experienced aid workers about how things had been in the 1960s and 1970s. Some had worked in the Biafran War, and had learned from a collection of papers published just after World War Two.3 Through this connection, I was given a tip off about the significance of Royal Army Medical Corps feeding procedures in Belsen camp. It was here that some British army doctors trialed influential emergency systems, including the invasive administration of protein solutions on emaciated survivors, with varying degrees of success. I visited their archives, where I found some fascinating material, which appears in chapter six and seven of the book.

From here, I worked backwards and soon I had found a natural starting point in the form of the 19th century soup kitchen. This was so different from the systems in South Sudan that I could launch the book with a central puzzle. I set about explaining the contrast between the two, emphasizing how hunger relief changed from Victorian soup kitchens, which were a locally-based, usually amateur process of communal feeding as a form of social control, to modern humanitarianism, which is a more technical, medicalized, highly individual process that aspires to scientific precision and tries to stand outside of politics. This last point was significant, since the classical principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence have for many years attempted to place humanitarian action in a moral rather than political space, with the rationalization and medicalization of feeding schemes becoming crucial to this transition.

In other words, whereas Victorian soup kitchens governed admission through personal references and assessments of moral character by respectable members of the community, modern emergency feeding schemes determine admission through impersonal bodily measures. Whereas the Victorian soup kitchen distributed common foods in a communal kitchen, emergency nutrition has provided technical foods designed for individual consumption. Whereas the Victorian soup kitchen was quite explicitly a tool or social control, contemporary humanitarian relief tries to purify itself of political and social positioning, presenting itself simply as the most rational way to save human lives and relieve suffering in extremis.

When it came to the argument of the book, a big challenge was to shake off the narrative of improvement that always hung behind recent accounts. I wanted to maintain a form of ethnographic skepticism, and show how there was a series of complex tradeoffs that had brought us to the present. I therefore decided to frame the book around the pressures of modernity. These transitions were not a simple case of progress, but I did not want to adopt a narrative of decline, either, or ›Whig history in reverse‹ (as critics of Foucault’s skeptical histories have called it). I therefore argued that there were many tradeoffs. With the bureaucratization of relief, we got efficiency, but lost compassion. With individualization, we got greater equality, but less cultural understanding. With the medicalization of relief, we gained efficacy, but this came with some insidious new forms of power. My aim was to show how broader changes in society led to different ideas of the empty stomach, which shaped the most technical sides of relief and had often ambivalent results. The way humanitarians operate, I concluded, cannot float free of context and operate in this neutral, impartial, scientific space as they often claim. Aid is always embedded in society, in culture, and in politics – right down to its most minute, technical practices.

In a certain sense, your book is a bit atypical for a scientific and (very much) research-based monograph. It focuses on two centuries of hunger relief – or rather on the changing practices and accompanying mindsets (or the other way around?) – in this vast field. You could have chosen a shorter period or a different design (and maybe you even worked on other ideas and options, which is quite common during most people’s research/writing process). Why did you end up with this exact design and time frame? What are the benefits of such a longue durée perspective that does – at the same time – focus on very specific case studies and actually also on certain practices on the micro level?

I certainly set myself a challenge when writing a book with such a broad sweep of history, and I was acutely aware that I was opening myself up to criticism due to the broad brushstrokes that became necessary to construct a narrative like this one. The first draft of the book was indeed narrower, as I initially focused on the international work of the 1930s and 1940s that laid the foundations of contemporary humanitarian feeding, looking particularly at the way these evolved into more ambitious high modernist schemes for new types of food from waste products. I had a number of side projects at the time on different forms of famine food, looking into the way these fitted into what I now call ›low modernism‹ – a modernist approach with faith in scientific progress but a more pragmatic and commercial mindset. While doing this work, however, it became increasingly clear that there were early historical moments that had left important remnants in the 1930s, not least the metaphor of the human motor and the connections between dietary studies and imperial rule. It then seemed important to understand what these ideas had been responding to, as the origins of modern humanitarianism itself occurred at the same time as the birth of nutritional science. What followed was a more expansive design for the book that pushed the narrative back another hundred years.

In making this move, I wanted to write a book to stimulate debate. My aim was to produce an organizing frame that might help make sense of the long history of emergency nutrition, and that might allow other scholars to interact – either by inserting their own research into the same structure, or by pushing back and finding examples that did not quite fit into my own themes and arguments. In writing this big picture history, I also did not want to lose the colour. This is such a great topic because it is so tangible. Readers can feel this visceral connection to the emergency foods and aid projects because they imagine what it was like to eat the concoctions created by others. I wanted to tell some clear and specific stories about, for example, the thick gloopy bottles of Liebig’s Extract of Meat, the jelly-like curd of Leaf Protein Concentrate, the sickly sweet cauldrons of Bengal Famine Gruel, and the Single Cell proteins grown in vats on a gasoil substrate. I picked out a number of the more interesting examples and I imagined these as little moments of detail within a bigger structure – like pins that you can drop into a board and then weave together with the wider theoretical narrative. Taken together, I hope these demonstrate a range of different approaches to food and the idea of the empty stomach.

The main benefit of this approach was that it provided a structure, something for other people to interact with, and an argument that could stimulate further scholarship. It also allowed me to cover a number of important changes in intellectual history, such as the rise of nutritional science, the use of diet as a form of governance in prisons, and the role of food in Taylorist industrial efficiency. I explored the study of diets in colonial rule, the relationship between war and emergency feeding, and then the high modernism of the postwar world. The disadvantage, of course, is that all this involved broad brushstrokes at times, but I was always aware that this was not a standard work of history. My doctoral work at Oxford was supervised by an historian, but also by an anthropologist, and so my work has always been closer to historical sociology or historical anthropology than history in its more classical form.

This may be a reflection of how history is considered in a relatively traditional institution such as Oxford, but I see the difference as lying in the questions one asks at the start and the way that theory is built in the process. Works of more traditional history may also consider wide periods of time, but with less of a focus on questions that are rooted in contemporary empirical work. This book is in some ways a ›history of the present‹ as sketched out in the work of historical sociologists, but I would suggest that it is more anthropological in character because, whereas historical sociologists are more likely to be interested in big social structures, in the history of class and the nation and how these came to be, I am more interested in smaller-scale patterns of everyday life – hence the anthropological starting point. Throughout this research, I was always concerned with how the everyday procedures of aid work had been changing.

This last comment of yours gives us the opportunity to dig a little deeper on one (or actually two) things: Firstly, we have been discussing rather intensively how both perceptions of hunger and practices and institutions in the field of hunger relief in the 20th century have increasingly been shaped by certain (juridical) categories and very distinct technical terms that are often shared across countries and organizations. Many of these categories or terms have a direct link to the language of human rights; others emerged in the context of international diplomacy. Many of these terms do not only describe something, but they also ›create‹ certain situations or establish certain problems – which then trigger a number of responses that are perceived to be ›adequate‹. In your book, you provide quite an interesting genealogy of certain practices related to hunger (relief). Do you think a similar genealogy of juridical categories and related technical terms might help us to gain further insight into international dynamics of hunger relief? And secondly (but related to this question): Who – in your opinion – are the players that coined and keep coining these categories and how? Do we still have to look to governments and state bureaucracies? Or have International Organizations and maybe even private players actually taken over in very many fields?

I would be fascinated to read a study of how specifically juridical categories have had an influence on hunger relief, not least because my focus has always been on the more technical level. It seems to me that the increasing professionalization and specialization of aid work, particularly since the Biafran War (1967–1970), has led to silos in which certain categories have purchase in some areas of the aid industry but not in others. My work has so far focused on nutritionists and their technical practices, which leaves questions of law, sovereignty and international strategy to other aid specialists and reduces the problem to bodies that are deficient in nutrients and foods that are the mechanisms for delivering those nutrients. Yet there will, of course, be a cadre of experts further up the aid architecture that no doubt shape the broad architecture of aid policy using legal and diplomatic categories.

On your second question about the source of these categories, I think it depends. One of the most influential ways that aid workers at the field level have made sense of the world around them is through military techniques such as the logframe, or logical framework analysis. This is a way of ordering the world that reduces complex and ever-changing processes into bullet points, a grid that makes events more amenable to action. It originated in the military, like many other bureaucratic systems in the aid world. So it is not just language or systems of rhetoric that organize the world but also material practices and objects such as charts and technologies, that – if you take an actor-network approach – work together with discourse to have an influence.

These military origins are common in other material forms as well. The refugee camp was imported from military camps, with the same aim of providing a complete system for supporting life in a temporary settlement away from urban centres. Early humanitarian rations were built on long-lasting foods for the navy, such as hard tack. And even more recent emergency foods have similar origins – such as BP-5, which began as a lifeboat ration for the Norwegian navy.

NRG-5 (by a German enterprise) and BP-5 (by a Norwegian enterprise), 2014

(Wikimedia Commons, Johannes Pribyl (Jokep),

Detailed Comparison NRG-5 BP-5 (Pribyl), CC BY-SA 3.0)

This Special Issue emerged (at least partly) out of a summer symposium in Hannover Herrenhausen on International Hunger Relief. At this event, we also invited a number of practitioners to see how historians, medical practitioners, nutritionists and relief workers would be able to relate to one another. We had the feeling that some debates were very fruitful and uncovered the distinct logics and ethical dilemmas both scientists and practitioners were confronted with. However, there were also issues that were not really touched, as perspectives and actual practices differed too much. Interdisciplinarity raised many questions, too, and we felt that these will have to be addressed much more in the future. What is your take on this? Did/do you really cooperate with practitioners and what follows from this exchange for your work? And do you think that practitioners can or even should work more with what historians – doing research on the history of relief – have to offer? What could be the outcome of closer reception and/or cooperation here? What are the perils?

This is a fascinating question. In this research, my cooperation with practitioners was relatively limited to the beginning and end of the project. It was inspired at the very start by interviews with aid workers, but beyond that the research remained academic because very few practitioners had knowledge of the transitions that I was trying to uncover. Some were simply not interested in it – they were focused quite understandably on the complications of their work in the present. Others felt that I had taken an overly relativistic approach in doubting, at the start, that their settled methods might not be the most effective way to tackle hunger. In the book’s conclusion, I described a memorable moment when I received almost opposite feedback from an audience of aid workers and an audience of anthropologists. The aid workers pointed out that there was an element of indulgence in much academic critique and they wanted to focus on something narrow – getting nutrients into people as quickly and effectively as possible. They saw little benefit in widening attention to the broader political and social environment. In contrast, many of the anthropologists were preoccupied with the wider environment and reluctant to engage in any discussion about what might work in humanitarian emergencies. They preferred to interrogate what it means for things to ›work‹, for whom, and how. I think this demonstrates your point about the challenges of interdisciplinarity. A similar dynamic would exist with scholars across disciplines, too.

As to your question on whether practitioners can or even should work more with historians, my answer would have to be yes. That was the core motivation for this project from the very start – to contribute something to this little-known story about the history of the sector, and to bolster the view (shared by certain academics and aid workers) that a lack of historical awareness is a problem. It is rather trite, but nevertheless true, to say that those who are ignorant of the past may be condemned to repeat it. I observed how common this is in the aid world when reviewing a development project a few years ago. I was doing some work as a consultant, attempting to bring greater critical thinking into aid evaluations, and at the very end of the review, when I was just writing up my final report, I realized that an evaluation with very similar questions had been conducted just a decade previously. I dug out the report, and its recommendations were almost identical to my own. Yet the staff that commissioned me did not even know that this earlier report existed. The reason, of course, was that there was no proper archiving in the organization and most of the older aid workers had left. Many important files were kept in boxes in the basement and then thrown away. The report had even been digitized, but it was buried in an obscure folder in a shared drive.

My experience of working in the aid sector as well as in the academy has certainly taught me that discussion between academics and practitioners is key. It can help foster greater appreciation for the past that might prevent this kind of issue from occurring, and it can teach scholars about the constraints under which humanitarians are constantly operating. Despite the purely academic content of much of this book, I tried at least to stimulate some thinking towards practical change at the end. The problem with a great deal of contemporary relief, I argued, is that it places both the immediate circumstances and the wider structural conditions in parentheses. The peculiarities of the social, cultural, and political environment tend to be obscured because aid workers reach for standardized procedures that are set out in emergency handbooks. At the same time, the root causes of any particular crisis take second place, as there is an emphasis on the need for an immediate and urgent response.

This is a structural feature of the aid world that many humanitarians know very well but find it difficult to transcend. When I summarized four lessons that emerged from this situation at the end of the book, therefore, I tried to do it in a form that might allow greater debate but without being prescriptive. I began by suggesting that, in nutrition projects, form matters, culture matters, ambition matters, and participation matters (pp. 180-183). In other words, the use of standardized procedures, stripped from context, have led humanitarians far too often to an idea of food that is simply a vehicle for nutrients, and of people as decontextualized bodies that need these nutrients to survive. Yet food has deep cultural, social and political significance that needs to be appreciated, and, as a result, we need more emphasis on the form of foods that people actually want to eat. We also need more emphasis on foods that are culturally appropriate, and an appreciation of how culture is important to people – even when they are starving to death. We also need a more ambitious appreciation of the food system more broadly, and we need to involve recipients more closely in nutrition work. These are very general lessons, and I am by no means the first to make some of these points, yet they emerge so strikingly from the historical record and continue to be missed in humanitarian discussions that too often search for a technical fix. The depth and repetitiveness of these four common mistakes in humanitarian nutrition still surprises me when I delve into the archives.

As historians, we do of course focus on our ›topics‹ and related arguments first. It is, however, highly interesting to look at the bigger picture a bit and also assess long- and short-term trends in a field that has been growing continuously over the past decades. Among the many intertwined fields that are of interest, we have the history of hunger and hunger relief, humanitarian history, the history of (development) aid, the history of international relations and diplomacy, the history of welfare, the history of international organizations and NGOs, the history of agriculture and agricultural markets… In your view, how are these different fields interrelated and is there a ›history‹ (and maybe even currents or cycles of) historians’ focus on hunger and the fight against malnutrition?

Yes, I think they are absolutely related, and the great richness of this topic is the way it straddles so many different areas and produces such different scholarship. One could tell a thousand different versions of this story about hunger relief – either focusing on science and technology, as I have done, or alternatively on agricultural reform, imperial rule, political transformation, international relations, and so on. James Vernon recognized as much at the start of his fantastic book on the topic, Hunger: A Modern History, when he noted how many disciplines and sub-disciplines have become central to the subject. Like me, he also looked at how ideas of hunger have changed, but with more attention on its political implications.4 His focus was on how hunger gained growing political significance in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whereas I examined almost the opposite process – how humanitarians used technical practices to increasingly remove hunger from politics. Yet there were some similar reference points in both books.

I have not really thought about how we might map all this onto wider historiographical trends, because my sense is that the literature is still emerging. I would be very interested in your reflections. I am in little doubt that my chosen focus will be considered very much of its time in the future – especially once the influence of STS has waned, as that focus on technical objects has been something of an intellectual fashion lately. I have a sense that things are fast moving. There was certainly very little written on histories of humanitarianism until around a decade ago, although if we broaden out to consider histories of philanthropy more generally, we can trace the rise and fall of Marxist approaches and the rise of cultural history. A good article on some of these themes appeared in Past and Present a few years ago.5 I suppose it depends where we draw our boundaries in a discussion of ›humanitarianism‹. Do you two have any sense of how we might periodize this work?

The question of periodization and also of how to connect all the narratives and historiographical perspectives we mentioned above is indeed one that we have been thinking about a lot. As a matter of fact, it’s almost impossible to tell the story of a post-war food aid regime without talking about the Cold War, governments’ incapacity to regulate agrarian overproduction, the impact of agrarian lobbyism, organizational logics and ›field practices‹ of humanitarian NGOs and IOs, the rise of development thinking and international attempts to find new ways of regulating trade tariffs, etc… And of course, every historian cares about genealogies, about similar practices or institutions that have been there before, maybe even leading up to the situation one is focusing on. However, finding that ›it’s all connected‹ and that our own research somehow ties in with the work others have been doing may not be all there is, especially if dealing with long time periods and large geographical spaces. We noticed that historians sometimes tend to ›like‹ continuities and connections much better, thus disregarding ruptures, endings, or competing trends, ideas or practices. We do sometimes wonder if discontinuities and dead ends may somehow deserve more attention.

And this leads us now to our next question: From reading your book we felt that its focus is in many regards more on making connections and on pointing out gradual developments – which is of course a great offer to the readers and something we enjoyed immensely while reading your book. We were wondering, however, if a stronger focus on turning points, discontinuities, even ruptures may have offered, at some points, slightly different insights. Addressing the 1930s and 1940s, we read: ›Humanitarianism was becoming more and more a matter of narrow nutritional expertise, concerned with getting nutrients to the right place, in the right format, at the right time.‹ (p. 88) How would you react to the idea that the history of World War II in this respect is predominantly a history of not getting nutrients to the right place at the right time and that WWII therefore can be understood as a rupture within the historiography of relief? Or, to put it in another way: Since hunger relief in many regions of occupied Europe during WWII was rather an exception than the rule, do we not miss this return of hunger and malnutrition on a scale not known in Northern and Western Europe in the 20th century and devastating even in the Soviet Union with her own history of famine if our narrative focuses on evolutionary developments?

I certainly agree that the Second World War was not necessarily a success when it came to getting nutrients to the right places at the right times, but my point was rather that this had become central to the ideals of humanitarianism for the first time. The humanitarian planners had narrowed their concerns and, rather than thinking expansively about the connections between nutrition and other sectors (such as agriculture, health and the economy – as they had in the interwar period), they focused on the mechanics of starvation and the efficiency of different foods for moving nutrients around the world. I suppose we might see this as rupture, but many of the same individuals were involved in changing the scale of intervention and shifting to the more medicalized view we see today. In any case, I did not mean to imply that they succeeded in getting nutrients to the right place, in the right format, at the right time. Rather, my point was that this became the aim in a way that it had not been before. Hopefully my skepticism about the postwar approach is clear in this book, especially in view of the damaging reductionism, the lack of ambition, and the manifold cultural and social errors in trying to design a universal modernist food with good nutritional balance.

More broadly, however, I can see your point that moments of profound change in any history can make the search for a single thread or story quite difficult. I think the impact of this depends on the lens or focus one is going to take. There was indeed something quite distinctive about the scale of hunger and malnutrition in occupied Europe, which generated completely new conversations and approaches (and, I also think, a degree of political interest in the issue by the 1930s and 1940s that was simply absent in earlier periods). Yet I still believe that, when we focus at the technical level as I did in this book, we can trace ways in which these periods connect. The same humanitarians were often coming to terms with new conditions, building new systems and refining old ones. Similar humanitarian nutritionists were writing up their handbooks and procedures, advocating new approaches and focusing on different things. These could be quite distinctive, but they were reacting to something that came before. I would not consider this to be a form of ›evolutionary development‹ and certainly not a linear form of progress, but I think it allows us to trace a narrative arc through these various approaches to the empty stomach – at least at the technical level.

You are currently working on a new project on Sir John Boyd Orr (1880–1971), the First General Director of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and surely one of the names everyone working on agriculture, hunger and research on hunger relief has come across at some point. What is your focus and what do you aim to uncover with your new research project?

Yes, this study of John Boyd Orr is very much an extension of my project on humanitarian nutrition. He was in fact one of these figures that bridged different eras, as we were discussing a moment ago. The research project began when I had finished On an Empty Stomach, and, when I re-read some sections, I felt I had done Boyd Orr a disservice. I had focused mostly on his role in the 1920s, when he was an imperialist and involved in some essentializing studies of different ›African tribes,‹ yet I had not written a great deal about his later life, when he became the first director of the FAO, an activist on world hunger, and an advocate for redistributive global government. The more I read about Boyd Orr, the more fascinating the story became. He began life as a nationalist and a conservative, developing all the trappings of an establishment figure (with military awards, a knighthood, a peerage, and working for the colonial service, etc), but he ended his life as a radical political figure, a peace activist and internationalist advocating a global food policy based on human needs. My project is to uncover how this transformation came about.

I am interested in the history of Boyd Orr’s ideas, then, as an example of how people change their views, but I also hope that this can also tell us something about how bold policy ideas end up accepted or rejected on the world stage. It is possible that John Boyd Orr’s radical notion of a World Food Board might have had a chance in that post-World War II moment, just as he had successfully advocated for free school milk in Britain. Interestingly, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949 as much for a vision that he represented (but had failed to realize) as for anything he had actually achieved. In any case, if we are to build a more just and positive world out of the disruptions of the current global pandemic, I think we learn a lot about the unusual political insights and bold policy plans of people like John Boyd Orr.

This sounds like an absolutely fascinating and timely project and we do very much look forward to learning more about it. However, when reading through your answer, one thing came to both of our minds: Boyd Orr was one of these ›big men‹, a handful of prominent male figures, that coined both international discourse about global hunger (eradication) and that pushed an organization to the fore, that – in his opinion – was best equipped to do it. Given recent historiographical trends and debates about gender relations: What can we (still) learn from biographies of such ›big men‹? May a figure such as Boyd Orr also offer a chance to address the question of gender relations in this field a bit more prominently? This is perhaps also an interesting question even beyond Boyd Orr: What is your assessment of the role that changing gender relations play in the fields you are focusing on? Can we understand practices of hunger relief without addressing gender as a central perspective?

I’m not sure if it is fully correct to say that Boyd Orr was involved in pushing an organization that he thought was best equipped to tackle global hunger. In fact, Boyd Orr was extremely reluctant to take on leadership of the FAO, because he thought it had not been given the necessary authority and resources to actually make any difference. He had much bolder and more radical ideas about international organizations, but accepted the appointment with a great many misgivings while trying to transform its constitution into something more assertive and activist (his proposals for a ›World Food Board‹, for example were at the center of these attempts). Boyd Orr’s ideas soon butted up against the straightjacket of national interest, state sovereignty, and financial constraint, and he left the organization after only a few years with some bitterness, then channeling his idealism into campaigns for peace and global government. So I think there is a great deal to learn here from the hidden story of the ›big man‹ – or, to put it bluntly, from the failures and the ideas that became moribund as much as from his high profile. In other words, I think Boyd Orr is so interesting not because he had a significant role in shaping our world (which some might present as a justification for a biography such as this), but rather because he didn’t have much influence. Many of his biggest ideas failed to take root, and he seemed to have changed his emphasis and perspectives numerous times over the course of his life.

But you are of course correct that this was a very male-dominated environment, and I completely accept the point that there are limitations if this is the only kind of history being written. There are other ways, I believe, to delve into mainstream figures and nevertheless tell surprising stories. I am interested in this particular career through its nuances, dead ends, and changing views rather than as a single, dominating personality. And when it comes to hunger relief I think Boyd Orr represents the end point of a transition in which humanitarianism as a whole shifted from being a classically ›feminine‹ concern in the 19th century, with negative connotations and overtones of mawkishness and sentimentality, to becoming associated with a more ›masculine‹ narrative of heroism, engineering, and life-saving scientific invention. Underneath this surface there have been all sorts of specific gender relations among individuals that have changed both policy and practice. In On an Empty Stomach, I saw this most clearly in humanitarian handbooks that were laden with gendered assumptions. Yet I agree that there is a lot of work still to do. With the Boyd Orr project, I will certainly give gender relations more thought as the research progresses.

This last point about the shift of humanitarianism from being associated with a female (often religious) sphere to a more masculine ›expert‹ culture is extremely interesting. I (Heike) remember being absolutely struck by the figure of the male company man being cultivated within the NGO CARE for instance. There were of course also a few female figureheads from the onset of the organization (especially for fundraising in New York – even very prominent figures such as Olive Clapper6 for example), but generally speaking, the NGO was very male dominated, with upper management being almost entirely run by men, up until the 1980s (and in the 1980s, CARE eventually lost a class action lawsuit, including allegations of sexual harassment). Apparently, there is a certain connection between increasing professionalization and more men pursuing aid work as a career – for CARE this also led to astoundingly high wages, by the way… I do feel, however, that male preeminence in this sector has waned quite a bit. Do you share this impression? And if yes, what prompted this shift to more females working in the relief field again?

That is a very interesting point about CARE. I remember, when reading your book,7 I had a very clear sense about the work that went into this construction of a new bureaucracy. That professionalization extended across the whole industry at the time, too, which no doubt had a role in solidifying these changes. There were many former soldiers at the end of the Second World War looking for new work and secure jobs after demobilization. They worked at many levels in the aid world. I remember speaking to a retired aid worker from Save the Children who said that lots of military men joined the organization in that period, which changed the organizational culture quite considerably (they also brought with them those processes developed by the Royal Army Medical Corps among others, I was referring to earlier). Another aid worker I spoke to described the post-war period, up until the 1980s, as the ›Age of Heroes‹. I think it was partly tongue-in-cheek, but he was referring to the classically masculine way that humanitarians in this time valued their heroic scope for independent action. They would travel the world, operate often alone or in small teams, and they were a long way from communication from head office. With only the odd letter or telegram, these men (and the point is that they were mostly men) could make decisions and develop programs with few constraints or accountability. This allowed a great deal of freedom, experimentation and what must have subsequently seemed like a glorious absence of bureaucracy, but there were many loose cannons with power and little oversight. It all changed by the 1990s, of course, with strategic planning, centralized control, and very regular communication between headquarters and the ›field‹.

I agree that male preeminence has changed since then, although my thoughts on this are rather anecdotal and I would like to see some data. Certainly by the time I worked in the aid industry, in the early 2000s, there were more women than men, although (of course) the men still tended to dominate senior management positions. This might be a gendered assumption of my own, but I wonder if this change has something to do with better HR systems and much greater attention to risk. I suspect that some of the men in the 1960s and 1970s reveled in the absence of systems and the hazardous excitement of many environments. Philip Gourevitch has suggested that the postwar generation of aid workers were seeking for some kind of alternative to the military honor that their fathers had gained in the Second World War. As he put it, they were seeking glory on the battlefield without having to kill anybody – they wanted to experience adventure and take action, but also do good. They did this by flying into places like Biafra on military planes and handing out food.8 My sense is that, by the 1990s, this kind of macho attitude was waning and a second wave of professionalization – with proper planning, participation, and protection for staff – called for new skills and attracted a different cadre of workers. This is just my personal theory, though, and I could well be wrong.

Thanks a lot, Tom, for this highly interesting conversation! There are so many more things we could talk about, but maybe it is just right to end our interview with new ideas for promising research questions and topics that deserve to be explored in greater depth in the near future.

Notes:

1 For more information, see: <https://www.qeh.ox.ac.uk/people/tom-scott-smith>.

2 See for example: <https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000v8qh>. Editorial note, 10 November 2022: See also the review by Mario De Prospo, in: H-Soz-Kult, 10 November 2022.

3 W.R.F. Collis, Belsen Camp: A Preliminary Report, in: British Medical Journal, 9 June 1945, pp. 814-816; F.M. Lipscomb, Medical Aspects of Belsen Concentration Camp, in: Lancet, 8 September 1945, pp. 313-315; P.L. Mollison, Observations on Cases of Starvation at Belsen, in: British Medical Journal, 5 January 1946, pp. 4-8.

4 James Vernon, Hunger. A Modern History, Cambridge, Mass. 2007.

5 Matthew Hilton/Emily Baughan/Eleanor Davey/Bronwen Everill/Kevin O’Sullivan/Tehila Sasson, History and Humanitarianism: A Conversation, in: Past & Present 241 (2018), pp. e1-e38.

6 Olive Ewing Clapper, One Lucky Woman, New York 1961.

7 Heike Wieters, The NGO CARE and Food Aid from America, 1945–80. ›Showered with Kindness‹?, Manchester 2017.

8 Philip Gourevitch, Alms Dealers: Can You Provide Humanitarian Aid without Facilitating Conflicts?, in: New Yorker, 11 October 2010, p. 104.