- Antifascist Solidarity with Chile

- From Antifascism to Narratives of Personal Suffering

- The Discourse of ›Genocide‹ and the Argentinean Dirty War

- Resistance, Tyrannicide, and Revolution: Chile Solidarity in the 1980s

- Conclusion

[The author wishes to thank the two anonymous reviewers and Jan-Holger Kirsch for their incisive comments and helpful critiques. A fellowship from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD, German Academic Exchange Service) facilitated research for this article.]

The 1970s are rightly seen as having been seminal for developments that continue to shape the early 21st century. Entrenching many central features of the contemporary world such as modern environmentalism, feminism, and neoliberalism, the 1970s were pivotal years in the efflorescence of today’s ubiquitous human rights discourse.1 The decade also marked the end of a predominantly left-wing vision of internationalist antifascism. Since the 1950s, West German antifascists had been at the forefront of campaigns of solidarity against what they saw as rising neo-fascist regimes abroad, especially in the Global South. In particular, left-wing West German students had come to see a politically volatile Global South as the harbinger of world revolution. For them, only world revolution would overthrow capitalism, which they identified as latent fascism.2

One of the most significant campaigns was the advocacy movement against the Chilean and Argentinean military regimes. Atrocities from East Timor, Cambodia, and Uganda were ignored, but West Germans threw themselves into solidarity with Chile and Argentina. While not identical, both campaigns were part of a movement to defend the progressive Left against a reactionary far-right onslaught. Another important motivation was that conditions in Latin America reminded many Germans of their country’s National Socialist past. Finally, another specific feature of these campaigns is that while decidedly left-wing actors first drove them, liberals and conservatives joined and shifted them in a more humanitarian direction.

Protesters initially saw the militarist style of Chilean capitalism as an insurgent fascism that could only be defeated with a decidedly antifascist revolution. The present article demonstrates that, as the decade progressed, the solidarity campaigns began to appeal to morality rather than revolution. The reasons for this were varied. Intra-left splits tarred antifascism with the brush of doctrinaire leftism. Successive governments in the 1970s and 1980s, from Helmut Schmidt (1918–2015) to Helmut Kohl (1930–2017), identified antifascism with an emotional leftist pathos incompatible with their foreign policy objectives. As antifascism lost its political force, it was gradually supplanted by an ethics of human rights and Holocaust remembrance marshalled by Amnesty International advocates, feminists, liberal Social Democrats, and conservative Christian Democrats – in short, the set of advocates that took the reins from the Left.

Their ethics has come under criticism for its failure to prevent the surge of economic inequality in the past forty years. On the one hand, human rights are accused of being ›minimalistic‹ and ignoring the economically needy.3 On the other, Holocaust remembrance has been criticized for focusing so much on the singularity of the Shoah, and particularly the symbol of the concentration and extermination camp, at the expense of other forms of antisemitism, racism, discrimination, and exploitation.4

This article reassesses the shared origins of human rights and Holocaust remembrance in West Germany out of the ashes of antifascism. It does so by exploring this transformation from the vantage point of grassroots advocates. While all activists framed their actions by referencing the National Socialist past, they did so out of a plurality of reasons. This is a story of roads taken and roads left untrodden. Among those who championed human rights in the 1970s, there were many who continued to understand their advocacy as antifascist, and even as a struggle against capitalism. Similarly, for many memory advocates who energized a much-needed reconsideration of the enormity of the Holocaust, combating more contemporary forms of racism and oppression was also on the agenda. This article contributes to three distinct yet interrelated fields of contemporary history: human rights, social movements, and memory politics. It utilizes published and archival sources from left-wing groups, human rights organizations, political parties, and government officials, and draws on interviews with activists.

1. Antifascist Solidarity with Chile

West Germany was no stranger to advocacy on behalf of foreign refugees and against foreign dictatorships. In its first twenty-four years of existence, it had witnessed campaigns for refugees from Hungary and Czechoslovakia, on behalf of Algerian anticolonial guerrillas, and minorities in the Global South such as Nigeria.5 At this point in history there was no established culture of Holocaust remembrance that recognized that the Shoah had been perpetrated with the knowledge and acceptance of much of the German population at the time. This culture came into being following global screenings of the 1979 American TV series Holocaust, when Auschwitz became the paradigm against which all other massacres were measured.6 The Historikerstreit (Historians’ Debate) of the 1980s also largely ended attempts at relativizing the enormity of the Holocaust.7

Nevertheless, activists had deployed the memory of the National Socialist era in selected cases to buttress their causes. For instance, the Social Democratic novelist Günter Grass spoke openly of ›Völkermord‹ (genocide) during the Biafran War (1967–1970), while humanitarians such as Rupert Neudeck and Tilman Zülch understood their task of rescuing Vietnamese boat people or indigenous people ›threatened by genocide‹ as a latter-day reckoning with their country’s murderous past.8 In all these cases, the usually non-white victims of atrocities were depicted as pitiful creatures worthy of German compassion, not only for the sakes of the needy, but also as a sort of German redemption. Thus, the memory of National Socialism served to enshrine a salvific view of human rights advocacy that emphasized protection against bodily harm and privations of life, shelter, and, in a few instances, civic rights.

Left-wing internationalists interpreted the memory of NS crimes in fundamentally different ways. As Michael Rothberg has shown, decolonization in the 1950s and 60s brought forth an efflorescence of comparisons between European colonialism and Nazi genocide.9 During the Algerian war in the 1950s, West German and Algerian critics of the French war of counterinsurgency charged France with replicating Nazi tactics and employing ›Gestapo-like methods‹.10 The United States war in Vietnam was routinely decried as ›fascist‹ in the large anti-war demonstrations of the 1960s.11 Neither of these campaigns bred a human rights movement, whereas the mobilizations against the Chilean and Argentinean regimes did. Human rights advocates helped transform the way in which the memory of National Socialism was employed to stoke an abhorrence of contemporary atrocities. This was not a foreordained conclusion, however. This section explores how, for a time, left-wing antifascists monopolized the movement against the Chilean military dictatorship.

On 11 September 1973, following increasingly violent unrest between supporters of the Popular Unity (Unidad Popular, UP) government headed by the Socialist Salvador Allende, and its detractors from the right, amidst an economic crisis and domestic and external sabotage actions, the Chilean armed forces renounced their neutral stance and violently unseated the government. The military coup stood out for its rarity in the Chilean political context. The wanton violence that the military unleashed upon the Chilean Left shocked many worldwide. The images were broadly disseminated. The general who directed the coup, Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, became an embodiment of ruthlessness and bloodthirstiness.12

The shock went well beyond the left-wing milieu. Many West Germans were genuinely outraged by the rounding up of government supporters, the public burning of leftist propaganda, and the images of dead civilians in the streets of Santiago.13 The small minority of West German leftists who had evinced interest in the ›peaceful path towards socialism‹ before the military coup was able to amplify their viewpoints using images of the atrocities in publications such as the Chile-Nachrichten (Chile News). The West German ambassador in Santiago de Chile, Kurt Luedde-Neurath, was irritated about the ›mostly one-sided‹ and ›tendentious‹ narratives that circulated in West Germany about Chile. The Ambassador was sure that bilateral relations were headed for a downturn.14

One of these ›tendentious‹ narratives was the consensus that Chile had fallen to the forces of fascism. The term ›fascism‹ was employed in a very inflationary manner in 1960s-70s West Germany, so it deserves careful treatment. Historians such as Michael Schmidtke, Quinn Slobodian, and Frank Biess have shown that New Left activists appropriated references to the Holocaust to cast themselves as ›new Jews‹ victimized by the West German political establishment. Their use of the Nazi past deliberately elided the particularities of the Holocaust in order to move away from the elegiac remembering that had become the standard narrative since the 1950s. According to New Leftists, the focus on innocent individual suffering, such as Anne Frank’s for instance, robbed the Holocaust of its political meaning. They were heavily influenced by classic Marxist-Leninist interpretations of fascism, and thus considered Nazism intrinsically connected to capitalism. Consequently, they had sought to mobilize the memory of genocide to turn it into a language of political action.15 According to Biess, ›the New Left [was able] to avoid a confrontation with the specific German past and instead practice an emotional identification with the abstract principles of anti-imperialism‹.16

Yet, in the case of Chile, the identification with anti-imperialism was not abstract. And neither were all those who believed that a type of Andean fascism was on the rise simply clueless New Leftists. One of the first to claim that the Chilean coup was fascist was the renowned anti-Nazi Protestant theologian Helmut Gollwitzer (1908–1993). At a teach-in at the Haus der Kirche in West Berlin on 14 September 1973, the veteran antifascist spoke before a rapt audience. His listeners heard that Chile was an example of how ›capitalism relies on fascism when it senses a threat to its existence‹. For the nonconformist theologian who had belonged to the Confessing Church, there were clear ›parallels between today and 1933‹. There was only one solution left for West German activists: to engage in solidarity with the ›thousands who are being starved and tortured in the concentration camps of the generals‹.17 The Weimar-era antifascist Walter Fabian (1902–1992) saw it with similar eyes. Asked about whether signed appeals of solidarity were helpful, Fabian responded by pointing to his own experiences as a persecuted Social Democrat under the Nazis. ›For the antifascists‹, Fabian observed, ›every signal of solidarity is of incalculable help‹.18 Gollwitzer was an undogmatic socialist theologian who advocated for collaboration between Marxists and Christians. He later became a prominent supporter of Amnesty International. Fabian was a left-wing Social Democrat, trade unionist, and former émigré who had barely escaped Nazism. Their understanding of ›fascism‹ stemmed from their antifascist formation forty years earlier.19

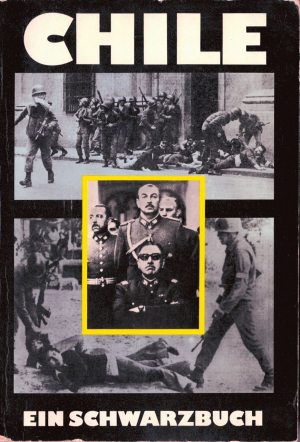

Veteran antifascists were certainly not the only ones employing the trope of fascism. Chile: Ein Schwarzbuch (The Black Book of Chile) took a similar discursive approach to Gollwitzer and Fabian. The 1974 publication by Hans-Werner Bartsch, Martha Buschmann, Gerhard Stuby and Erich Wulff, intellectuals affiliated to the Moscow (and East Berlin) loyalist German Communist Party (DKP), was especially adamant in its juxtaposition of the repression of the Left by the Nazis with the ongoing repression in Chile. The iconic image of the bombardment of the Moneda Presidential Building by the Chilean Air Force, the symbolic shattering of Chilean democracy by the armed forces, was placed alongside the burning Reichstag in February 1933, which the Nazis used to mount a witch hunt against the Left. The rounding up of Social Democrats by the SA was pictured alongside the rounding up of UP supporters; the burnings of leftist propaganda by the Chilean military with the infamous book burnings of leftists and Jewish writers by the Nazis. An image of a train loaded with antifascists dated 1933 complemented a picture of downcast Chilean government supporters behind bars in the National Football Stadium. For the authors there was no doubt that its actions and pronouncements unmasked the junta’s fascist goals. It was the ›descendant of fascist dictators [...] flesh from its flesh‹.20

As DKP affiliates, the writers of the Schwarzbuch employed a discourse of antifascist human rights that had been crafted in Communist East Germany, which saw its engagement for human rights as a continuation of its antifascist loyalties. Its ultimate aim was to strengthen the legitimacy of the East German regime.21 Erich Wulff would go on to head the Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Committee with Asia, Africa and Latin America, which had its main office in Frankfurt am Main. The Committee, founded in early 1973, focused on uncovering ties between West German politicians and business leaders and anti-Communist governments in the Third World. The Committee was part and parcel of the wider network of DKP-affiliated groups throughout West Germany that worked to advance the viewpoint of the GDR regime.22 The GDR had, moreover, entertained excellent relations with the fallen Chilean government. The coup was perceived as a bitter setback for Communist bloc aspirations in Latin America.23

Though similar at first sight, these uses of the language of fascism for the Chilean situation originated from two disparate camps of an increasingly fractured West German Left. From undogmatic leftists and Social Democrats to DKP sympathizers, all used the heuristic of fascism to understand the Chilean military coup. But they meant different things and their goals were fundamentally distinct. Yet, at this point in time, leftists as dissimilar as Helmut Gollwitzer and Erich Wulff were united by a common fear, which partly explains the immediacy of Chile. They were concerned that Chile provided a playbook for reactionaries confronted with a peaceful transition to socialism. After all, with the exception of the radicals of the Red Army Faction (RAF) and the K-Gruppen (sectarian Communist Groups), left-wing West Germans hoped, and some even firmly believed, that the Federal Republic of Germany could undergo a democratic transition to socialism. In contrast to this, notable Christian Democrats such as Karl Carstens, Bruno Heck, and Franz Josef Strauß had relativized the actions of the Chilean military and expressed misgivings about the solidarity movement. Such statements were of profound concern to antifascists.24

Writing for the liberal weekly DIE ZEIT, the jurist and scholar Martin Kriele observed that conservative approval of Allende’s forced removal had ›a domestic goal: local »leftists« are to be taught and warned that changes of the socio-economic system of the Federal Republic could have very negative consequences‹.25 For the Chile-Nachrichten, an influential monthly magazine published by the West Berlin Chile Committee, conservatives were ›apprentices of the Junta‹.26 After visiting Chile in the late autumn of 1973, Jakob Moneta (1914–2012) compared Bruno Heck to an unwitting tourist visiting Nazi Germany in 1933, who had allowed himself to be blinded by the official propaganda.27 Moneta was a veteran trade unionist and Social Democrat with Trotskyite leanings who had been persecuted both for his Jewish heritage and political opinion under the Nazis. For Moneta, solidarity with Chile was crucial in order to nip a renascent fascism in the bud. For a younger generation of Social Democrats such as Heinz Beinert (1929–2018), solidarity with Chile was equal to ›combatting the reaction in our own country‹.28

The most important outcome of labeling the military regime in Chile ›fascist‹ was that it drove the Social Democratic government of Willy Brandt to accept refugees from Chile. Brandt (1913–1992) was an internationally recognized antifascist veteran. One of the major pillars of the Social Democratic Party’s self-legitimation after 1945 was its unequivocal anti-Nazi attitude since the 1920s, encapsulated by Brandt’s 1969 remark that with his election as Chancellor, Hitler had truly lost the war.29 The SPD’s antifascist narrative, however, could be hurt if they did not demonstrate the same zeal towards the Chilean cause as their youngest supporters. Solidarity activists close to the SPD, particularly the Young Socialists, demanded that the government accept refugees from Chile.30 Younger Social Democratic parliamentarians such as Karl-Heinz Walkhoff (b. 1936) openly compared the plight of Chilean refugees with that of ›persecuted Germans‹ who had found ›help and succor in countries such as Chile thirty years ago‹.31

However, the SPD-led government worried that Latin American radicals might enter Germany disguised as refugees. If they opened the doors to left-wing refugees from Chile – an unprecedented move, since the only refugees to gain asylum in West Germany since 1945 were anti-Communist eastern Europeans – the SPD would open itself to charges from the CDU/CSU opposition that they were putting internal security at risk. The conservatives had already signaled their absolute opposition to the admission of political refugees from Chile, claiming that these people were dangerous leftist extremists who would only add to the domestic security threat posed by the left-wing terrorists of the RAF.32

8 December 1973. One of the posters reads:

›Nice words by the SPD do not help any refugee.‹

(bpk 70135953, photo: Konrad Giehr)

Brandt’s antifascist legacy served the solidarity movement, which could count on the support of the powerful Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB, German Federation of Trade Unions), the Young Socialists and the Young Democrats, and notable Social Democratic politicians such as Hans Matthöfer, to pressure the government on Chile.33 ›Mr. Federal Chancellor, [you] enjoyed asylum abroad during the Nazi period‹, read a joint letter by the West German Chile Committees that utilized the German past to advocate on behalf of the admission of Chilean refugees. ›Had other states behaved like the F[ederal] R[epublic of] G[ermany] is doing now, many refugees of the Nazi terror [would] not [have] survived.‹34 Bonn was forced to relent to public pressure, and instructed a reluctant Luedde-Neurath to open the Embassy’s doors. Chilean refugees would reach an estimated 2,500, not including relatives, by the end of the decade.35

2. From Antifascism to Narratives of Personal Suffering

Antifascism had been premised on a rejection of sentimentalism and an acknowledgment of the socio-economic context of cases of state violence such as the military coup d’état in Chile. The question at stake is why the solidarity movement turned towards narratives of the suffering of innocent individuals from the mid-1970s onwards. In order to answer this question, we must understand why antifascism collapsed so ignominiously – and we must learn more about the activists’ various motivations.

In the years 1975/76, the dream for a common antifascist front ended in West Germany. The K-Gruppen attempted to utilize Chile solidarity for their narrower political goals. The enmity between the Soviet Union and China had reverberations in the West German solidarity movement with Chile. For instance, on the anniversary of the military coup, several Maoist and anti-authoritarian leftist groups mustered 20,000 demonstrators in Frankfurt. On the surface it was an impressive show of unity that caused alarm at the conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung about the political potential of the ›ultraleft‹.36 But the Moscow loyalists from the DKP rejected the Maoist demand that Chile’s leftist parties should arm workers as ›revolutionary zealotry‹. The DKP, paradoxically, labelled their calls an attempt to interfere with the resistance within Chile.37

Demonstration of more than 40,000 people from Germany, Italy, Chile, Greece, Spain, and other countries, Frankfurt am Main, 10 May 1975 –

thirty years after the end of World War II and the ›fascist‹ Hitler regime.

(picture-alliance, photo: Klaus Rose)

The strong rifts between ›anti-authoritarians‹ and ›dogmatics‹, and between Brezhnevites and Maoists, effectively ended any dreams of a common leftist front against the Chilean regime. Chilean exiles were no less divided. The Communist Party and the Movement for the Revolutionary Left (Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria, MIR) blamed each other for the military coup.38 Following the crushing of the MIR by 1975, and the effective destruction of the Communist and Socialist Parties by 1978, the question of armed resistance in Chile became academic.39 These divisions not only enervated the solidarity movement, but also coincided with a retrenched attitude amongst government officials towards left-wing appeals of solidarity and specifically towards political refugees from Latin America.40 If Chancellor Brandt’s antifascist past had allowed activists to pressure him, his successor Helmut Schmidt’s legacy as an officer in the Wehrmacht (former German Army) left little recourse on that front.41

Moreover, developments in Chile caused activists to reassess the nature of the regime. Undogmatic leftists who had been amongst the most adamant purveyors of the fascism discourse started to come around to the view that the military regime was probably not fascist. Pinochet, they recognized, did not have a genuine popular mass organization. Indeed, the regime’s intellectual foundations did not allow it to build a populist base of support. Its most important ideologue, Jaime Guzmán, was fundamentally opposed to communitarianism and rejected any sort of populist pandering. Rather, the new state was to follow a corporatist model, which was later abandoned for Hayekian-style neoliberalism.42 After two years, the Chile-Nachrichten also changed their tune. By 1975, it recognized that ›in Chile there is no fascism in a robust sense of the term, since the military junta does not enjoy the support of a mass movement‹.43

The final element in the displacement of the antifascism rhetoric was the influx of Social Democrats, feminists, Amnesty International, and Christian groups into the Chile Solidarity Movement. Their reading of the past was not infused with the militant antifascism of the student movement or the K-Gruppen. For instance, red-tainted antifascism was the last thing that the West German section of Amnesty International wanted. Amnesty was already under fire from conservatives and liberals who alleged that it was too left wing. Their offices had been occupied by protesters who wanted to liberate the imprisoned members of the RAF, and Amnesty’s leadership had been internally criticized for having called the police to clear the space.44 Therefore, as far as Amnesty’s public stance was concerned, memory would be mobilized as a depoliticized language of human rights that highlighted individual suffering at the expense of socio-economic contextualization.

One could interpret this shift to a more minimalist version of human rights advocacy as an abandonment of so-called progressive politics. However, I would argue that this shift was premised on the lack of alternatives for political action in the mid- to late 1970s. The growing emotional identification with the victims of Nazism that also emerged during that decade played a role in the withdrawal from militant antifascism, too. In West Germany, the human rights activist and Lutheran pastor Helmut Frenz (1933–2011) became a central personality in the solidarity movement during the mid-1970s. He drew on the substantial moral capital of having been forced to return from Chile by the military authorities because of his energetic engagement on behalf of politically persecuted Chileans. Frenz was uniquely suited to explain what was happening in Chile because he had witnessed it first-hand. Upon arriving in West Germany in the autumn of 1975, Frenz promptly got involved in the campaign for the acceptance of Chilean refugees. Now that Schmidt was Chancellor, the government had reduced admissions of political refugees.45

But at the very moment when the advocacy movement was needed more than ever, it was on the verge of disappearing. ›There is no unified pro-Chile [movement] in the FRG‹, Frenz wrote to a group of friends that he intended to enlist for a grassroots lobby group for the admission of Chilean political refugees. ›The forces have divided themselves in hundreds of groupings [and] have exhausted themselves in internal egoist rivalries.‹46 The only way to move beyond these divisions was to form a common platform grounded on human rights. For Frenz, human rights may have been humanitarian in tone, but remained deeply political at its core.47 He did not shy away from pointing out that ›Pinochet and his system are part and parcel of the Western world, economically, politically, and ideologically‹. From his point of view, the only reason for government refusals to accept more political refugees was the ›irrational anti-Communism‹ that governed the FRG.48

Human rights advocacy was qualitatively different from earlier forms of political advocacy. Frenz’s mobilization of the memory of National Socialism reflected this transformation. He shied away from blanket remonstrations against fascism. Instead, he focused on the individual suffering of refugees by linking them to the victims of National Socialism. Frenz utilized his invitation to the 1975 Social Democratic party congress (Parteitag) to criticize the Schmidt government. Preventing Chileans from entering the Federal Republic on account of their political loyalties, Frenz claimed, meant accepting the logic of the junta. ›For me it sounds as though we were still using the files of Mr. [Roland] Freisler to judge on political cases of the Nazi era‹, the pastor told his Social Democratic listeners in Mannheim, a number of whom had been direct victims of Nazi jurors.49 Equating the President of the Nazi People’s Court – infamous for his alacrity in handing down death sentences to the enemies of the Nazi state – with the Chilean junta also enabled Frenz to liken Chilean political refugees to the anti-Nazi resistance.

Liberal Social Democratic supporters of the acceptance of political refugees rationalized their engagement on behalf of Chilean refugees by pointing to their own victimization by, or their personal memories of, the Third Reich. One of them was Bremen’s Social Democratic mayor Hans Koschnick (1929–2016). His vocal support for the admission of refugees had earned him criticism from conservative Bremen residents. Koschnick faced down his opponents by arguing that there was a specifically German duty to advocate against the transgressions of states and human rights violations. Koschnick argued that the difficulties persecuted Germans had encountered when seeking asylum in the 1930s effectively compelled modern-day Germans to be welcoming towards refugees: ›Sometimes I have the feeling that in the matter of Chile, citizens today are as blind as the English and French were during the persecutions here in the time after 1933. Since my parents were victims of this blindness, I will not be silent: Neither towards the Soviet Union nor towards Chile! I do not want the coming generation to be guilty of ignoring the suffering going on in Chile, or even sanctioning evil.‹ Koschnick saw his engagement on behalf of Chilean refugees as following in the footsteps of German resisters against the Nazis. He concluded his letter with a poem by Albrecht Haushofer, a conservative diplomat who had turned against the Nazis and been murdered in 1945, who blamed himself in his last poems from prison for having delayed too long in resisting.50

By the end of the 1970s, the amorphous specter of fascism had been largely displaced. Human rights advocates drew on very specific examples from the German past such as the Nazi witch-hunts of communists, forced emigration, and genocide. Even before the 1979 screening of the American TV series Holocaust, said to have marked a ›turning point in the popular and scientific representations of the National Socialist era‹, human rights advocates tapped into a growing acknowledgement that ordinary people had abetted the Shoah, and an equally growing collective identification with the victims.51 This was not limited to the solidarity movement with Latin America. For example, advocates for the acceptance of Vietnamese Boat People such as Marion Gräfin Dönhoff raised funds by pointing to the Holocaust and the German expellees after 1945. A group of CDU delegates even claimed that failing to help the Boat People ›makes us complicit with a new Holocaust‹.52

Leftists employed similar arguments to rescue Chilean refugees. Feminist solidarity groups compared the victimization of female political prisoners to the oppression at Nazi concentration camps. Feminists claimed that gender violence was ignored by male antifascists. The grassroots group Frauen helfen Frauen (Women aiding Women), created by Chilean and West German feminists in West Berlin, mobilized the memory of Nazism to raise awareness about the fate of women imprisoned in Chilean concentration camps such as Tres Álamos. The group focused its efforts on the case of María Cristina López Stewart, a MIR member, who had been seized, tortured, and impregnated through repeated rapes by ›guards, officers, and specially trained dogs‹. Frauen helfen Frauen claimed that women were ›victimized as political and racial undesirables were in the concentration camps of the Third Reich‹. They called on readers to act against the military regime’s ›bestial sexism‹ by contributing with time or money to the group’s efforts. For the feminists, ›today we cannot say that we did not know anything. What goes on in Chile, daily and hourly, is everyone’s business.‹53

Some Latin American refugees also seized on the comparison of their comrades’ victimhood to the victims of National Socialism. They included the painter brigade Brigada Luis Corvalán, composed of Communist Party-affiliated Chilean painters Gracia Barrios, José Garcia, José Martinez, Guillermo Nuñez und José Balmes. The brigade painted a mural on the walls of the University of Bremen that drew on Holocaust imagery to relate the experience of military rule to the West German viewer. The artists embedded figures of ›barbed wire, silhouettes of heads, Stars of David, and the motif of the Jewish boy from the Warsaw Ghetto‹, in a middle section devoted to the persecution, sandwiched between a brightly colored representation of the Allende years, and an equally colorful and hopeful depiction of a post-dictatorial future.54 The painting’s portrayal of victimhood was so poignant that it rendered the political affiliation of the painters invisible. The emphasis on individual victimhood, linking the innocence of the Jewish boy raising his hands in surrender to the grassroots revolutionary excitement of the Allende years, was innocuous enough even for West German Amnesty to utilize it in a brochure about the practices of seizure and disappearance pioneered by the Chileans and perfected by the Argentineans, entitled: ›Chile: Imprisoned… tortured… disappeared‹.55

West German art students. This mural, originally one of three parts, measures 3 by 21 meters. Having suffered weather damage after some decades, it was reconstructed on a smaller scale in 2014.

(University Archive Bremen, 7/B-Nr. 69/4, photo: Marlis Glaser, 1976 or later)

3. The Discourse of ›Genocide‹ and the Argentinean Dirty War

The debate about Third World fascism had largely spent itself by the time of the 1976 military coup in Argentina. Unlike the situation in Chile, the martial rhetoric of the Argentine junta was rife with fascist and genocidal tropes.56 There were strong fascist and anti-Semitic precursors in Argentine militarism.57 Nevertheless, the West German reaction to the coup was negligible. As I have demonstrated elsewhere, this was the result of a conjuncture of factors ranging from growing apathy, reluctance to support people perceived as terrorists in the age of the RAF, and a sense of inevitability, given Argentina’s long history of autocracy in the twentieth century.58 Moreover, as discussed above, antifascism had acquired a left-wing taint unsuited for human rights work. The Third Russell Tribunal on the situation of human rights in West Germany only underscored this. Held in Frankfurt am Main in 1978, the Tribunal was opposed by all political parties and ignored by the larger public, showing the limitations of human rights advocacy perceived as too overtly political.59

West German activists were confronted with the question of how to motivate everyday people to care about the fate of Argentineans persecuted by their government. In the absence of political solidarity with those persecuted, as had existed with Chile, they turned to personal testimonies in order to generate empathy. Specifically, they turned to the Latin American practice of testimonio. This is the telling of personal stories of victimization that ›[perform] an act of identity-formation which is simultaneously personal and collective‹.60 Such testimonial performances became a particularly influential human rights practice from the mid-1970s on. Individuals who had been subjected to torture and persecution told their stories to visiting members of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, in congressional hearings in Washington D.C., and to Amnesty International activists and sympathetic journalists, who disseminated their plight far and wide.61 The military regimes disputed the neutrality of these activists, castigated such hearings as communist propaganda, and actively promoted their own narrative that they were protecting their citizens from totalitarian communism.62 In response, human rights activists in West Germany supplemented these testimonies with citations by victims and survivors of National Socialism. Their purpose was to highlight a common humanity that transcended contemporary political divisions.

For instance, the poet and Amnesty activist Urs M. Fiechtner (b. 1955) linked Latin testimonio with writings by Holocaust survivors and former members of the German resistance in the forewords of several of his publications. His purpose was to convey a sense of continuity between the crimes of German Nazis and Latin American generals, and also between their victims. The first book of a series entitled an-klagen (accusations), which he founded together with the Chilean exile writer Sergio Vesely for the financial benefit of Amnesty International in 1977, featured a foreword by Jean Améry (1912–1978), the famous Austrian essayist of Jewish descent and Auschwitz survivor. Améry compared Amnesty’s advocacy to a scream against despotism. He was ›thankful when young people [...] scream, on behalf of me who cannot scream anymore, because I belong to those hit by adversity‹ at a time when ›no one screamed‹.63 Inge Aicher-Scholl (1917–1998), the sister of Sophie and Hans Scholl, who were executed in 1943 for being part of the anti-Nazi White Rose student group at the University of Munich, wrote the foreword for the next volume. Scholl linked her own experience of imprisonment under the Nazis and the death of her siblings to the experience of the victims of military dictatorships in Latin America.64

As an Amnesty International activist, Fiechtner was opposed to the narrow sectarianism of the dogmatic Left. Yet he does not shy away from describing his human rights work as antifascist in my interview with him. Unlike others in the solidarity movement, Fiechtner believed that the Chilean and Argentinean regimes were indeed fascist. Fiechtner’s antifascism was certainly the product of his upbringing. His father served as the Bundeswehr military attaché in Chile, Peru, and Bolivia for the better part of the 1950s and early 1960s. His earliest childhood memories were of donning a Prussian-style military uniform at the celebrations of the Day of the Glory of the Chilean Army, and serving Bommerlunder spirits to his father’s guests for the yearly celebrations of Hitler’s birthday. Walther Rauff, a former member of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office) and later of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (Federal Intelligence Service), was a regular guest, and Fiechtner called him ›tío Walther‹ (uncle Walther).65 As a young man Fiechtner rebelled against his militaristic upbringing, becoming a pacifist, poet, and a human rights activist. He had to overcome significant opposition from his father and his teacher when he joined Amnesty International as a teenager.66

However, Fiechtner’s understanding of how to respond to this fascism was substantially different from that of the earlier solidarity movement. No longer concerned with world revolution, Fiechtner’s antifascist work was to highlight the torture and disappearance of individuals in Latin America, and the indifference of the West German government towards these human rights violations. His work reflects the changed conception of the Third World subject that emerged with human rights activism. No longer heroic and fearless, the subject of advocacy was suffering in a dark prison and was profoundly afraid.

Similarly, the journalist and historian Osvaldo Bayer (1927–2018) invoked the memory of Germany’s National Socialist past to escape the apathy towards the ›genocide‹ that was occurring in his native Argentina. Bayer had barely escaped the clutches of the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (Alianza Anticomunista Argentina, AAA), a death squad that wantonly murdered leftists and was condoned by the civilian government that preceded the military regime. He had found asylum in West Germany thanks to the actions of a sympathetic embassy employee and his German ancestry. Like other Argentine leftists, from Rodolfo Walsh to the Argentine Human Rights Commission (Comisión Argentina de Derechos Humanos, CADHU), Bayer considered the ›Dirty War‹ to be a genocide. His reasons cannot be reduced purely to expediency following Emilio Crenzel’s argument regarding the high international visibility of the crime of genocide in the 1970s, which gave ›denunciations that fell under that category‹ greater visibility.67 Bayer’s essay on the subject reveals a far more profound apprehension regarding the German ability to reckon with the past.

Bayer believed that West German foreign policy towards the Argentinean junta demonstrated authoritarian, militaristic, and fascist continuities between the Third Reich and the Federal Republic.68 He had been especially incensed by a fact-finding mission to Argentina organized by the Social Democratic Party in late 1978. At a time when West German deliveries of weapons and nuclear technology to Buenos Aires were booming, and Bonn was refusing to admit Argentinean refugees, three Social Democratic Bundestag delegates, headed by Willfried Penner, had visited Argentina.69 Once back in Germany, the three made excuses for the ›military’s war against subversion‹. Bayer saw here an expression of a German propensity to side with militarism and genocide.70 He wondered how the West German government could entertain friendly relations with a regime that had endorsed burnings of books by Jewish authors such as Freud, Marx, and Einstein in a repeat of the Nazi-instigated book burnings at Berlin’s Opernplatz in 1933.71 How could they entertain good relations with a regime that held prisons such as ›Sierra Chica and Coronda, Chaco and La Pampa‹ that recreated ›the opprobrium of Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, of Oranienburg and Dachau‹?72 ›Delegate Penner‹, Bayer observed, ›reminds me of those satisfied Yankees that visited Nazi Germany as tourists and then declared: yes, you can see a few Jews in the streets wearing the yellow star, it seems that a few synagogues were burned, we did not see them, a few intellectuals have been detained and a few communists shot, but people look happy in the streets, everything is clean and orderly, and above all, there are no strikes.‹73

For Bayer, there were two Germanies. One was authoritarian, militarist, and fascist; the Germany of the ›petty torturers and tyrants – as Thomas Mann said – who hide behind the romantic windows and half-timbered houses of idyllic German cities‹.74 But he still held hope for the second Germany, a progressive and antifascist country. This was the Germany of luminaries such as Kurt Tucholsky, Robert Musil, Walter Hasenclever, and of the human rights activists he collaborated with.

The memory of National Socialism also served the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. This was a grassroots group composed of the mothers of politically persecuted individuals who had been seized by state security organs. The Mothers had gained worldwide prominence for their protest walks around the Obelisk in the Plaza de Mayo in defiance of the military regime since 1977. They established a partnership with West German Amnesty and with Urs M. Fiechtner in 1979. This led to yearly tours where the mothers – and eventually grandmothers – looking for missing children talked to West German politicians and church leaders and spoke before German audiences.75

One small subset of the mothers, thanks to their German background or marriage to Germans who had settled in Latin America, became the link between West German activists and Argentinean human rights organizations. The most significant role fell to Ellen Marx (1921–2008). She had escaped the Nazi dictatorship at the age of seventeen by fleeing to Argentina in 1939, and become the sole survivor of the Jewish Pinkus family of Berlin. Her daughter Nora Gertrudis had disappeared due to her ties with the left-wing Peronist group Montoneros. Marx and her West German allies were not oblivious to the uses of her specific case in getting the attention of the West German political establishment.76 She returned to Germany for the first time in 1983. There she introduced herself as ›a Jew from Berlin‹, and regularly told her listeners ›you Germans know what an authoritarian regime looks like‹.77 Marx’s background made it difficult for politicians to ignore her. Willy Brandt gave Marx a 45-minute audience and assured her of his support, while Chancellor Helmut Kohl devoted half an hour to her.78

![Chancellor Helmut Kohl welcomes Ellen Marx (right) and Idalina Tatter, two delegates of the Mothers of the Plaza del Mayo, 20 June 1983. (Bundesarchiv [Federal Archives], B 145 Bild-F065987-0027, photo: Harald Hoffmann)](https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/cumulus/2020-1/Botta/resized/6132.jpg?language=en)

two delegates of the Mothers of the Plaza del Mayo, 20 June 1983.

(Bundesarchiv [Federal Archives], B 145 Bild-F065987-0027,

photo: Harald Hoffmann)

That was the limit to which Marx was willing to utilize her past as a German Jew. She ›refused to compare the horrors of the Argentinean dictatorship with the Holocaust‹, because of the differences in scale and also because the persecution was not racially based.79 She rejected Urs M. Fiechtner’s proposal for her to succeed Helmut Frenz as General Secretary of the West German section of Amnesty International. Fiechtner was at pains to point out that this request was due to ›your personality, your deportment, not your background‹. He feared tokenizing her status as a Jewish survivor. At the same time, since he considered Amnesty to be part of ›the antifascist resistance‹ it was important ›not to hide this fact‹. In other words, what better way to symbolize the antifascist nature of Amnesty’s work than with a General Secretary with Ellen’s background? ›It is surely difficult‹, Fiechtner continued his letter, ›to ask you to work in Germany for two, three, or four years, [...] but the more I think about it, the more reasonable I think it is.‹80 Marx declined, citing concerns that the job would overwhelm her, but it was clear that she did not want to put herself in the limelight. Her activism was limited to telling Argentinean stories of individual tragedy, which prevailed on the listener or reader to be moved by a moral choice of right or wrong.81 But this reading of memory marshalled by human rights activists such as Marx did not preclude alternative narratives. In the mid-1980s, a militant reading of memory that approved of revolutionary violence made a comeback onto the West German political scene.

4. Resistance, Tyrannicide, and Revolution:

Chile Solidarity in the 1980s

As we have seen, Chile advocacy in West Germany had diminished since the mid-1970s, and become confined to the actions of a relatively small number of human rights activists such as Helmut Frenz and Urs M. Fiechtner. In their survey of West German internationalist activism since 1945, Werner Balsen and Karl Rössel argue that by 1980, ›Chile was no longer on the agenda‹.82 This apathy began to change with the rise of anti-Pinochet protests throughout Chile in the wake of the Latin American banking crisis of 1982–1983 that wrought havoc throughout the region’s budding capitalist economies.83 The crisis led to a resurgence of political violence in Chile. The Chilean Communist party sensed an opportunity and embraced armed violence through its militant arm, the Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez. The Frente, alongside the remnants of the MIR, engaged in numerous acts of terrorism against the armed forces, and also bank robberies. The regime hunted both groups with zeal. In September 1986, the Frente mounted an elaborate assassination attempt on Pinochet by attacking his armored motorcade. While five of his guards were killed, Pinochet himself survived, and the ensuing repression reminded many of the time immediately after the coup.84

For West Germans disillusioned by the persistence of the military regime, the outbreak of armed violence held some promise. The Lateinamerika-Nachrichten (formerly Chile-Nachrichten) bemoaned the failure of the assassination attempt and hoped that the Frente would be able to draw on support from within the armed forces.85 Overall, the 1980s in Latin America took a revolutionary turn following the successful revolution in Nicaragua in 1979, and the outbreak of the Salvadoran insurgency in 1980. Both reenergized the solidarity movement in West Germany. They also drove a wedge between those who welcomed the return of revolutionary violence and those committed to Amnesty-style human rights.

The 1987 political debate about whether to grant asylum to fourteen, later fifteen, Chileans who confessed to participating in terrorist attacks, including the assassination attempt on Pinochet, showed this most clearly. There was widespread fear amongst human rights activists that the accused would be sentenced to death based on evidence obtained under torture. The few advocates of revolutionary violence that remained were mostly concerned with saving freedom fighters from the gallows. By the spring of 1987 a campaign was underway to get Helmut Kohl’s Christian Democratic government to offer asylum to the accused. The staunchly conservative CSU Interior Minister, Friedrich Zimmermann (1925–2012), strenuously rejected these demands on internal security grounds. His position was that terrorists could not enjoy asylum in West Germany.86 Zimmermann’s position was rejected by the Greens and the Social Democrats, and also, to Zimmermann’s great annoyance, by a number of Christian Democratic and Liberal members of the ruling coalition.

Amnesty International had guidelines against adopting or supporting the cause of those who had advocated violence.87 It therefore remained on the sidelines of the debate. This prompted a dramatic change of attitude by Helmut Frenz. The strong advocate of nonviolent and not-overtly-political human rights in the 1970s changed his tune in the 1980s. Amnesty-style tactics of naming and shaming abusers, he conceded, had not managed to unseat the dictator. Having relinquished his post at Amnesty in 1985, Frenz argued that the assassination attempt had been a legitimate ›last instrument in a hopeless situation‹. ›The people‹, Frenz wrote in 1988, ›have a right to defend themselves against‹ Pinochet’s fifteen-year regime of terror – even with violent methods. The pastor turned human rights activist had become an advocate for tyrannicide.88

Frenz’s position on the Chilean resistance and his support for the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua demonstrated his rejection of the model of human rights advocacy that he himself had pioneered a decade before. Like Frenz, other grassroots solidarity groups and sympathetic politicians sympathized with the turn towards revolutionary violence in Chile. Yet how could they legitimate anti-state left-wing violence in a West German society traumatized by the RAF’s terrorism? The way they found was to turn to the German past, and recover an acceptable example of anti-government violence: the 20 July 1944 assassination attempt against Hitler.

Associating the fifteen Chileans with the German resistance – and particularly with Count Claus von Stauffenberg – became a primary tool in the repertoire of some Social Democrats and Green politicians. In a particularly contentious parliamentary debate in June 1987, Freimut Duve (1936–2020, SPD) warned the CDU/CSU against defending the Pinochet regime and thus appropriating the language of a dictatorship. Duve recounted that, like many others in the room, he had spent his childhood under the Nazi dictatorship. ›I remember the first radio message I ever heard. I listened to the speaker say that there had been an assassination attempt against the Führer.‹ As a child, Duve had been ›outraged‹, and seen the would-be assassins as ›criminals‹. After the defeat of Nazism, he remarked, ›we know better‹.89 For Duve, the act of attempting to murder Pinochet was not reprehensible in itself. Tyrannicide was a legitimate deed in his eyes not least because of Germany’s own experience of tyranny, and the public exulting of the conspirators who tried to assassinate Hitler. In September 1986, Duve had claimed that ›we cannot praise the perpetrators of July 20 as a shining attempt at tyrannicide and at the same time stamp Chilean would-be assassins as terrorists a priori‹.90

Some Green Party politicians argued along similar lines. Ellen Olms (b. 1950) minced no words in claiming that Zimmermann and the ruling government stood closer to ›the interests of a fascist dictatorship than to human rights‹. For Olms, Zimmermann’s refusal elided the difference between democracy and dictatorship, legitimized Freisler’s People’s Court death sentences, and ›prosecute[d] Stauffenberg a second time‹.91 Another Green delegate, Ludger Volmer (b. 1952), charged the government with hypocrisy for celebrating the actions of the would-be assassins of the 20 July assassination attempt but failing to recognize the ›legitimate militant resistance against Pinochet‹. Volmer even ventured into language with clear Holocaust symbolism, arguing that the asylum practices of the Kohl administration followed a ›selection‹ mechanism that decided who would live and who would die.92 The Peruvian-born Green Party delegate Germán Meneses Vogl (b. 1945), a veteran of the Chilean Solidarity Movement, also pointed to similarities between Count Stauffenberg and Chilean anti-regime activists. Meneses Vogl denied the charge that they were terrorists, arguing that in a dictatorship such as Chile there could be no terrorism. Since violence against a tyrant was legitimate, all of the prisoners were ›political prisoners‹ and were thus collectively eligible for political asylum.93

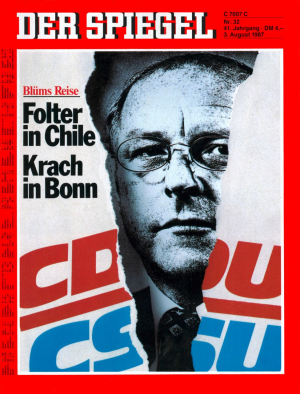

To Zimmermann’s chagrin, the liberal coalition partner, the Free Democratic Party (FDP), and a small number of Christian Democrats supported granting asylum. The case of the fifteen impelled the CDU Labor Minister Norbert Blüm (1935–2020) to visit Chile in late July 1987 to demonstrate West German interest in the case. Unexpectedly, Blüm received an audience with Pinochet. The dictator claimed that Blüm had no right to criticize his government because of Germany’s genocidal past. Blüm retorted that Germany’s past heinous crimes ›give me not only the right, but also the duty to do my part so that human rights are respected all over the world. That is my way of making amends.‹94 Pinochet responded by dabbling in Holocaust relativism. An astounded Blüm later recounted his exchange to fellow parliamentarians: ›He [Pinochet] said that his friend [Hans-Ulrich] Rudel had always remarked [that] Hitler only made one mistake: losing the war. […] I pointed to the six million murdered Jews. He [Pinochet] attempted to enter into a discussion with me as to whether there were only four million.‹95 Rudel (1916–1982), a highly decorated veteran of Hitler’s Air Force, had spent much of the postwar period as an advisor to several Latin American dictators and as a representative of West German companies. In West Germany, he gained prominence for backing neo-Nazi parties. By mentioning Pinochet’s friendship with Rudel, Blüm was underlining the affinity between Pinochet and National Socialism.

Blüm’s trip to Chile caused a major row between his supporters in the CDU and his detractors in the CSU. Some analysts, including DER SPIEGEL, believed that the historic alliance between the two parties could become undone over the issue.

Unlike Social Democrats and Greens, Blüm advocated the acceptance of Chilean political refugees on strictly humanitarian grounds. He refrained from validating the methods of the fifteen accused, and much less compared them to Stauffenberg. His message hearkened back to Hans Koschnick’s in the 1970s. Germans had a special duty towards safeguarding human rights. Blüm had the backing of his colleague Heiner Geißler (1930–2017), who also supported the admission of the fifteen refugees. However, Geißler denied that the acts committed by the fifteen could be equated with Stauffenberg’s ›ethical‹ act of violence.96 For Geißler, there was still a possibility of unseating Pinochet by peaceful methods. Geißler was later vindicated by the 1988 referendum that forced Pinochet to hand power to civilian governance in 1990.97

Using the memory of the German resistance to legitimize political violence was controversial because of the terrorism of the 1970s. Tarnished by the quixotic struggle of the murderous RAF against the West German state in the 1970s and 1980s, rehabilitating violent anti-state resistance was a tough sell in 1980s West Germany. Even amongst solidarity activists there was much ambivalence about supporting armed groups in the Global South. The campaign ›Weapons for El Salvador‹, launched in 1981 by the left-wing newspaper die tageszeitung, opened itself to harsh criticism from quarters ranging from the peace movement to hardened conservatives.98

By framing Chilean resistance actions as terrorism, conservatives denied the solidarity movement’s attempt to claim Stauffenberg for their own. If Stauffenberg’s deed had still been seen as an act of treason in the first decade of the postwar period, by the 1980s, the 20 July assassination attempt on Hitler had become a chivalric attempt at ending the life of Germany’s ›seducer‹.99 Predictably, conservatives rejected arguments linking Stauffenberg to left-wing Chileans engaged in armed combat against Pinochet. Christian Democrats concurred that Pinochet was not the same as Hitler, and that his removal did not necessitate violence. Moreover, innocent bystanders were bound to get hurt. Tortured terrorists could only be accepted on humanitarian grounds. Their deeds were not to be glorified or ennobled with the memory of the anti-Nazi resistance. Conservative human rights advocacy was grounded on a rejection of antifascism.100

Even though several Länder (German federal states) made offers, the Interior Ministry refused political asylum to the fifteen Chileans. Chancellor Kohl obliquely endorsed Zimmermann’s decision in a move designed to maintain the cohesion of his political coalition. The fifteen were eventually sentenced to lengthy prison sentences, which some of them served even after the reestablishment of democracy in 1990.101

Coming to terms with the National Socialist past in divided Germany was the subject of substantial political controversy, not only between East and West, but also within each half.102 Similarly, human rights were the ›stuff of contestation with no guarantees about the final result‹, as Jean H. Quataert and Lora Wildenthal have recently put it.103 In the case of the campaigns against military rule in Chile and Argentina, by the 1980s a humanitarian vision of what human rights were, and how the past should be interpreted to help advance them, won out.

Yet, as this article has demonstrated, it was a contested transition. Indeed, an explicitly left-wing antifascism had been ubiquitous in the early 1970s and had played a major role in the Brandt government’s decision to admit refugees from Chile. But intra-Left strife, a recognition that the Chilean regime did not have a mass movement, and, most importantly, the association of antifascism with political extremism, enervated left-wing antifascism. The political change from Brandt to Schmidt had profound repercussions on human rights activists’ mobilization of memory. Amnesty International advocates, Social Democrats, feminists, and even a few conservatives breathed new life into the effort to bring political refugees to West Germany and isolate the military regimes. A growing emotional identification with the victims of Nazism also contributed to the efflorescence of human rights arguments. Activists such as Urs M. Fiechtner reinterpreted antifascism in a far more concrete yet distinctly humanitarian frame, as the salvation of individuals.

The language of human rights that emerged in a new context of Holocaust remembrance was not just a product of an internal German dynamic of memory politics. Influences from Latin America’s culture of testimonio, and the voices of Latin American activists such as Osvaldo Bayer and Ellen Marx, marked a decisive contribution to the West German human rights movement. Bayer’s steadfast antifascist perspective, however, clashed with Marx’s ambivalence about connecting the extermination of her family in the Shoah with her daughter’s murder by a patently anti-Semitic right-wing regime. These were the same issues that baffled their West German counterparts. What were the limits to human rights advocacy? Should human rights advocacy be restricted to a politics of salvation? And what role should the National Socialist past play in human rights advocacy, if at all?

The mid-1980s saw a last-ditch attempt to revindicate an explicitly left-wing antifascism. Left-wing activists and sympathetic politicians, unsatisfied with the inability of human rights advocacy movements to definitively end abuses, sought to equate the 20 July assassination attempt on Hitler with the actions of Chileans who had attempted to assassinate Pinochet in September 1986. By doing so, they clashed with an anti-antifascist and humanitarian vision which their conservative counterparts had come to adopt. In a West German context that had abjured political violence against the state, the attempt to bring back ideas of tyrannicide failed to gain traction. Nevertheless, the debate in the mid-1980s shows that the vision of human rights advocacy as supplication and shaming was not the only option left.

Antifascism has lost much of its authority because of its association with dogmatic leftism and with the authoritarianism of Eastern European ›real-life socialism‹. While much of the criticism of antifascism is just, its vilification has led to a dangerous dynamic of positing the Shoah as a mere historical catastrophe that detracts from its present-day significance. While remembrance of National Socialist crimes is not indispensable to combat racist violence,104 there is no reason why memory should not prove a more helpful ally in the fight against everyday forms of discrimination and racism, and indeed human rights violations.105 Especially in Germany, the Holocaust has become part and parcel of national consciousness. Treating it as a specific German-Jewish event threatens to exclude the growing number of Germans with a migrant background.106

Moreover, an anti-antifascist narrative that threatens to reduce the twentieth century to ›a gigantic humanitarian catastrophe‹, as Enzo Traverso has aptly put it,107 only helps right-wing populists from the German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) to Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro.108 The twentieth century’s enormous death toll was the result of ideological struggles. The same was true of the abuses in 1970s-80s Latin America. Many human rights activists understood them as such, while others consciously withdrew from this perspective in the 1970s for the reasons given above. Understanding how advocates navigated the neoliberal NGO era of the 1980s-90s marks the present frontier for human rights scholarship. In the same vein, the upcoming challenge for the research field of social movements as a whole will be to understand how human rights and other so-called New Social movements fit into longer histories of activism and protest politics.

Notes:

1 See Niall Ferguson et al. (eds), The Shock of the Global. The 1970s in Perspective, Cambridge, Mass. 2010; Samuel Moyn, The Last Utopia. Human Rights in History, Cambridge, Mass. 2010; Akira Iriye/Petra Goedde/William I. Hitchcock (eds), The Human Rights Revolution. An International History, New York 2012. For the German case, see Frank Bösch (ed.), A History Shared and Divided. East and West Germany since the 1970s, trans. by Jennifer Walcoff Neuheiser, New York 2018.

2 Quinn Slobodian, Foreign Front. Third World Politics in Sixties West Germany, Durham 2012; Belinda Davis, New Leftists and West Germany: Fascism, Violence, and the Public Sphere, 1967–1974, in: Philipp Gassert/Alan E. Steinweis (eds), Coping with the Nazi Past. West German Debates on Nazism and Generational Conflict, 1955–1975, New York 2006, pp. 210-237, here p. 220.

3 Samuel Moyn, Not Enough. Human Rights in an Unequal World, Cambridge, Mass. 2018.

4 See Frank Biess, Republik der Angst. Eine andere Geschichte der Bundesrepublik, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2019, p. 441.

5 Patrice G. Poutrus, Asylum in Postwar Germany: Refugee Admission Policies and Their Practical Implementation in the Federal Republic and the GDR Between the Late 1940s and the Mid-1970s, in: Journal of Contemporary History 49 (2014), pp. 115-133; Lasse Heerten, The Biafran War and Post colonial Humanitarianism. Spectacles of Suffering, Cambridge 2017; Christopher A. Molnar, Imagining Yugoslavs: Migration and the Cold War in Postwar West Germany, in: Central European History 47 (2014), pp. 138-169; Florian Hannig, West German Sympathy for Biafra, 1967–1970: Actors, Perceptions and Motives, in: A. Dirk Moses/Lasse Heerten (eds), Postcolonial Conflict and the Question of Genocide. The Nigeria-Biafra War, 1967–1970, New York 2017, pp. 217-237.

6 Arguments such as that by Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider, who claimed that the memory of the Holocaust undergirded the creation of a human rights system as early as the 1940s, or Johannes Morsink, who argues that the lessons of the Holocaust permeate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, have lost their edge following Moyn’s convincing critique that there was no widespread understanding, nor a desire for it, of the Nazi genocide in the immediate post-war era. See Daniel Levy/Natan Sznaider, The Institutionalization of Cosmopolitan Morality: The Holocaust and Human Rights, in: Journal of Human Rights 3 (2004), pp. 143-157; Johannes Morsink, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Origins, Drafting and Intent, Philadelphia 2000; Samuel Moyn, Christian Human Rights, Philadelphia 2015; Frank Bösch, Zeitenwende 1979. Als die Welt von heute begann, Munich 2019, chapter 10.

7 See Charles S. Maier, The Unmasterable Past. History, Holocaust, and German National Identity, Cambridge, Mass. 1997.

8 Lasse Heerten, A as in Auschwitz, B as in Biafra: The Nigerian Civil War, Visual Narratives of Genocide, and the Fragmented Universalization of the Holocaust, in: Heide Fehrenbach/Davide Rodogno (eds), Humanitarian Photography. A History, New York 2015, pp. 249-274; Lora Wildenthal, Humanitarianism in Postcolonial Contexts: Some West European Examples from the 1960s to the 1980s, in: Eva Bischoff/Elisabeth Engel (eds), Colonialism and Beyond. Race and Migration from a Postcolonial Perspective, Zürich 2013, pp. 104-123; Wildenthal, Imagining Threatened Peoples: The Society for Threatened Peoples (Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker) in 1970s West Germany, in: Susanne Kaul/David Kim (eds), Imagining Human Rights, Berlin 2015, pp. 101-118, here p. 103; Frank Bösch, Refugees Welcome? The West German Reception of Vietnamese ›Boat People‹, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 14 (2017).

9 Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory. Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization, Stanford 2009.

10 Mathilde von Bülow, West Germany, Cold War Europe and the Algerian War, Cambridge 2016, pp. 111-128, here p. 111.

11 See Timothy Scott Brown, West Germany and the Global Sixties. The Antiauthoritarian Revolt, 1962–1978, Cambridge 2013, pp. 101-115.

12 The literature on the Chilean coup is substantial. For the best and most recent treatment see Tanya Harmer, Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War, Chapel Hill 2011. On Pinochet’s international image, see Jan Eckel, Die Ambivalenz des Guten. Menschenrechte in der internationalen Politik seit den 1940ern, Göttingen 2014, p. 608.

13 On the violence of the military coup, see Peter Winn, The Furies of the Andes: Violence and Terror in the Chilean Revolution and Counterrevolution, in: Greg Grandin/Gilbert M. Joseph (eds), A Century of Revolution. Insurgent and Counterinsurgent Violence during Latin America’s Long Cold War, Durham 2010, pp. 239-275.

14 Deutsche Botschaft (Kurt Luedde-Neurath) to Auswärtiges Amt, Berichterstattung über die Ereignisse in Chile in den deutschen Massenmedien, 19 October 1973, Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts (PA AA, Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office), Berlin, ZA, vol. 100586.

15 Slobodian, Foreign Front (fn. 2), pp. 146-147; Michael Schmidtke, The German New Left and National Socialism, in: Gassert/Steinweis, Coping with the Nazi Past (fn. 2), pp. 176-193.

16 Biess, Republik der Angst (fn. 4), p. 259. All translations from German are mine.

17 Helmut Gollwitzer, Schlussworte bei einem Teach-in, Berlin, 14 September 1973, in: File 23 ›Reaktionen in der Öffentlichkeit‹, Forschungs- und Dokumentationszentrum Chile-Lateinamerika (FDCL, Centre for Research and Documentation Chile-Latin America), Berlin. Also see the slightly modified English version: Helmut Gollwitzer, Learning from Chile, in: Christianity & Crisis. A Christian Journal of Opinion 34 (1974) issue 8, pp. 98-100.

18 Detlef Oppermann, Walter Fabian (1902–1992): Journalist – Pädagoge – Gewerkschafter, in: Gewerkschaftliche Monatshefte 54 (2003), pp. 409-420; Verbreitet die Wahrheit! 350 Publizisten, darunter Böll, Grass, Mann, Bloch, appellieren, in: Deutsche Volkszeitung, 19 September 1974.

19 Dominik Rigoll, Erfahrene Alte und entradikalisierte 68er. Menschenrechte im ›roten Jahrzehnt‹, in: Norbert Frei/Annette Weinke (eds), Toward a New Moral World Order? Menschenrechtspolitik und Völkerrecht seit 1945, Göttingen 2013, pp. 182-192.

20 Hans-Werner Bartsch et al. (eds), Chile: Ein Schwarzbuch, Cologne 1974, 3rd ed. 1981, p. 178.

21 Ned Richardson-Little, Between Dictatorship and Dissent: Ideology, Legitimacy, and Human Rights in East Germany, 1945–1990, PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2013, pp. 34-51; see also his book: The Human Rights Dictatorship. Socialism, Global Solidarity and Revolution in East Germany, Cambridge 2020. Also see Georg Dufner, West Germany: Professions of Political Faith, the Solidarity Movement and New left Imaginaries, in: Kim Christiaens/Idesbald Goddeeris/Magaly Rodríguez García (eds), European Solidarity with Chile, 1970s – 1980s, Frankfurt a.M. 2014, pp. 163-186, here p. 167.

22 Heike Amos, Die SED-Deutschlandpolitik 1961 bis 1989. Ziele, Aktivitäten und Konflikte, Göttingen 2015.

23 Over four thousand Chileans would arrive as refugees in East Germany, including the high-ranking Socialist Carlos Altamirano. See Inga Emmerling, Die DDR und Chile (1960–1989). Außenpolitik, Außenhandel und Solidarität, Berlin 2013; Sebastian Koch, Zufluchtsort DDR? Chilenische Flüchtlinge und die Ausländerpolitik der SED, Paderborn 2016.

24 Heck wirbt um Verständnis für die Junta: Allende durch totale Politisierung schuld am Putsch, sagt der CDU-Politiker, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 18 October 1973; Prof. Carstens zu den Ereignissen in Chile, in: Deutscher Union Dienst, 13 September 1973.

25 Martin Kriele, Gründe für einen Putsch: Wie und warum ›FAZ‹ und ›Welt‹ den Umsturz in Chile gutheißen, in: ZEIT, 28 September 1973.

26 CDU – Lehrlinge der Putschisten, in: Chile-Nachrichten Nr. 12, 18 January 1974, pp. 26-30, here p. 30.

27 Winfried Didzoleit, Im Dritten Reich sahen viele auch nur die Fahnen. Der Chefredakteur der Gewerkschaftszeitung Metall, Moneta, berichtet über seine Chile-Eindrücke, in: Frankfurter Rundschau, 4 December 1973.

28 Heinz Beinert, Solidarität mit Chile... heißt die Reaktion im eigenen Land bekämpfen, in: Blickpunkt, December 1973/January 1974, p. 34.

29 Kristina Meyer, Die SPD und die NS-Vergangenheit 1945–1990, Göttingen 2015, pp. 330-335.

30 See the letter from the Jungsozialisten-Projektgruppe Dritte Welt (Unterbezirk Düsseldorf) to Parliamentary Delegates Matthöfer, Vahlberg, Conradi et al., 11 February 1974, Holdings Jusos, SPD-Parteivorstand 7882, Archiv der sozialen Demokratie der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (AdsD, Friedrich Ebert Foundation Social Democratic Archive), Bonn.

31 Karl-Heinz Walkhoff (MdB [Member of the Bundestag], SPD) to Genscher, 24 October 1973, B 106/69037 File 2, Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

32 Felix A. Jiménez Botta, The Foreign Policy of State Terrorism: West Germany, the Military Juntas in Chile and Argentina and the Latin American Refugee Crisis of the 1970s, in: Contemporary European History 27 (2018), pp. 627-650.

33 See Felix A. Jiménez Botta, Embracing Human Rights: Grassroots Solidarity Activism and Foreign Policy in Seventies West Germany, PhD dissertation, Boston College, 2018, chapter 2.

34 Brief der Chile-Komitees an Brandt, in: Chile-Nachrichten Nr. 10, 1 December 1973, pp. 8-9.

35 See Georg Dufner, Partner im Kalten Krieg. Die politischen Beziehungen zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und Chile, Frankfurt a.M. 2014, pp. 280-286.

36 Jürgen Busche/Klaus Viedebantt, Eine Heerschau der deutschen Ultra-Linken. Die ›Nationale Chile-Demonstration‹ in Frankfurt, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 16 September 1974.

37 Freiheit für Chile: 80,000 kamen, in: Deutsche Volkszeitung, 19 September 1974.

38 MIR, Zum Dokument der Kommunistischen Partei: Der Linksradikalismus, das trojanische Pferd des Imperialismus, in: Chile-Nachrichten Nr. 36, 20 April 1976, pp. 59-68.

39 See Julio Pinto Vallejos, ¿Y la Historia les dio la razón? El MIR en Dictadura, 1973–1981 [Did History Prove Them Right? The MIR Under the Dictatorship, 1973–1981], in: Valdivia Ortiz de Zárate/Rolando Alvarez Vallejos/Julio Pinto Vallejos (eds), Su Revolución Contra Nuestra Revolución. Izquierdas y Derechas en el Chile de Pinochet (1973–1981) [Their Revolution Against Ours. The Left and the Right in Pinochet’s Chile (1973–1981)], Santiago 2006, pp. 173-205; Rolando Álvarez Vallejos, Desde las sombras. Una historia de la clandestinidad comunista (1973–1980) [From the Shadows. A History of Underground Communism (1973–1980)], Santiago 2003.

40 See Jiménez Botta, Foreign Policy of State Terrorism (fn. 32); Klaus J. Bade, Migration in European History, Oxford 2003, pp. 270-273.

41 On Schmidt’s troubled relationship with the Left, see Kristina Spohr’s rather hagiographical biography, The Global Chancellor. Helmut Schmidt and the Reshaping of the International Order, Oxford 2016.

42 Renato Cristi, El Pensamiento Político de Jaime Guzmán. Una Biografía Intelectual [The Political Thought of Jaime Guzmán. An Intellectual Biography], Santiago 2011, pp. 76-81. Also see Quinn Slobodian, Globalists. The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, Cambridge 2018.

43 3. Teil Widerstandskämpferinnen im Nazi-Deutschland gegen Faschismus, für Sozialismus!, in: Chile-Nachrichten, Sondernummer 3: Frauen in Chile, 8 May 1975, pp. 60-63.

44 Thomas Claudius/Franz Stepan, Amnesty International. Portrait einer Organisation, Munich 1977, pp. 228-229.

45 Jiménez Botta, Foreign Policy of State Terrorism (fn. 32), p. 641.

46 Helmut Frenz to ›dear friends and fellow campaigners‹, 18 February 1976, in: File ›Aktion zur Befreiung der politischen Gefangenen in Chile‹, FDCL.

47 Entwurf Manifest zur Gründung von Aktion Freiheit für die politischen Gefangenen in Chile oder Chilekomitee für Menschenrechte, in: File ›Aktion zur Befreiung der politischen Gefangenen in Chile‹, undated [1976], FDCL.

48 Pfarrer Frenz: Irrationaler Antikommunismus. Gründung einer ›Aktion zur Befreiung der Gefangenen in Chile‹ in der Bundesrepublik, in: Deutsche Volkszeitung, 16 September 1976. See also Caroline Moine, Christliche Solidarität mit Chile. Helmut Frenz und der transnationale Einsatz für Menschenrechte nach 1973, in: Frank Bösch/Caroline Moine/Stefanie Senger (eds), Internationale Solidarität. Globales Engagement in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der DDR, Göttingen 2018, pp. 93-121.

49 SPD-Parteitag in Mannheim, 11–15 November 1975, SPD Party Publication, Evangelisches Zentralarchiv in Berlin (EZA), Holdings 6, File 2388.

50 Hans Koschnick to Carl Richard Bünemann, 4 January 1977, AdsD, File 14349. On Haushofer’s complicated relationship with National Socialism, under which he served as professor and diplomat, see Ernst Haiger/Amelie Ihering/Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Albrecht Haushofer, Ebenhausen 2002.

51 Biess, Republik der Angst (fn. 4), p. 340.

52 Cited in Bösch, Zeitenwende 1979 (fn. 6), p. 199.

53 Frauen helfen Frauen, Helft den gefolterten Frauen in Chile, June 1975, in: File ›Flüchtlingsgruppe, Kampagnen, Aufrufe, Flugblätter‹, FDCL.

54 Amnesty International, Chile: Verhaftet... Gefoltert... Verschwunden, Düsseldorf 1978, p. 76. On the mural itself, see Klaus Matthies, Zugang nur durch die Wand. Wandmalerei in der Universität Bremen, in: Impulse aus der Forschung Nr. 8, October 1989, pp. 5-11, here p. 5; a more detailed description, 2008/14: <https://www.zentralarchiv.uni-bremen.de/kunstweb/chile.htm>; and a video commemorating the mural, 22 July 2014: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guRsdT_ruP8>.

55 Amnesty International, Chile (fn. 54), p. 76.

56 Marguerite Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror. Argentina and the Legacies of Torture, Oxford 1998, revised and updated 2011.

57 See Federico Finchelstein, Transatlantic Fascism. Ideology, Violence, and the Sacred in Argentina and Italy, 1919–1945, Durham 2010, and Finchelstein, The Ideological Origins of the Dirty War. Fascism, Populism, and Dictatorship in Twentieth Century Argentina, Oxford 2014.

58 Felix A. Jiménez Botta, Solidarität und Menschenrechte. Amnesty International, die westdeutsche Linke und die argentinische Militärjunta, 1975–1983, in: Bösch/Moine/Senger, Internationale Solidarität (fn. 48), pp. 122-151.

59 Hugh Mosley, Third International Russell Tribunal on Civil Liberties in West Germany, in: New German Critique 14 (Spring 1978), pp. 178-184. Also see Michael März, Linker Protest nach dem Deutschen Herbst. Eine Geschichte des linken Spektrums im Schatten des ›starken Staates‹, 1977–1979, Bielefeld 2012.

60 George Yúdice, Testimonio and Postmodernism: Whom Does Testimonial Writing Represent?, in: Latin American Perspectives 18 (1991) issue 3, pp. 15-31, here p. 15.

61 See William Michael Schmidli, The Fate of Freedom Elsewhere. Human Rights and U.S. Cold War Policy toward Argentina, Ithaca 2013; Lyndsay Skiba, Shifting Sites of Argentine Advocacy and the Shape of 1970s Human Rights Debates, in: Jan Eckel/Samuel Moyn (eds), The Breakthrough. Human Rights in the 1970s, Philadelphia 2014, pp. 107-124; Patrick William Kelly, Sovereign Emergencies. Latin America and the Making of Global Human Rights Politics, Cambridge 2018.

62 See Iain Guest, Behind the Disappearances. Argentina’s Dirty War against Human Rights and the United Nations, Philadelphia 1990; Eckel, Ambivalenz (fn. 12), pp. 653-660; Philipp Kandler, Anti-Menschenrechtspolitik. Der Umgang der Diktaturen in Chile (1973–1990) und Argentinien (1976–1983) mit der internationalen Menschenrechtskritik in den 1970er und 80er Jahren, PhD dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin 2019; book version: Philipp Kandler, Menschenrechtspolitik kontern. Der Umgang mit internationaler Kritik in Argentinien und Chile (1973–1990), Frankfurt a.M. 2020 (in print).

63 Autorenkollektiv 79 (ed.), an-klagen. Mit Vorworten von Jean Améry und Helmut Frenz. Schriften für Amnesty International 1, Tübingen 1977, 4th, revised ed. 1981, p. 8.

64 Autorenkollektiv 79 (ed.), Suche nach M. Mit Vorworten von Ingeborg Drewitz und Inge Aicher-Scholl. Schriften für Amnesty International 2, Tübingen 1978, 3rd, revised ed. 1981.

65 Interview Urs M. Fiechtner, Ulm, 16 August 2016. On Rauff, see Martin Cüppers, Walther Rauff – in deutschen Diensten. Vom Naziverbrecher zum BND-Spion, Darmstadt 2013.

66 Urs M. Fiechtner, Sex ’n’ Drugs ’n’ Rock ’n’ Roll... and Amnesty International?, in: Urs M. Fiechtner/Sergio Vesely/Cornelia Gräbner, Mit Möwenzungen in der Mehrzweckhalle. Kurzgeschichten, Berlin 2015, pp. 83-94.

67 Emilio Crenzel, The Crimes of the Last Dictatorship in Argentina and Its Qualification as Genocide: A Historicization, in: Global Society 33 (2019), pp. 365-381, here p. 370.

68 Osvaldo Bayer, Chronist aus eigener Meinung, in: Gert Eisenbürger (ed.), Lebenswege. 15 Biographien zwischen Europa und Lateinamerika, Hamburg 1995, pp. 53-62, here pp. 58-59.