- The Strutting Miner:

Masculinity and the Protection of Workers’ Rights - Wolves and Scabs:

Masculinity and the Limits of Power - Yesterday’s Men:

Muscular Masculinity and the Feminist Gaze - Conclusion

[The evocative characterisation in the main title is borrowed from Beatrix Campbell, Wigan Pier Revisited. Poverty and Politics in the Eighties, London 1984, p. 111. The question mark is my own. I would like to thank the editors of this Special Issue as well as the editors of this journal for their perceptive comments on earlier versions of my article. I would also like to thank Vera Marstaller and Dean Blackburn for their careful reading of various draft versions. I owe a special thanks to Paul Darlow, ex-miner and tireless custodian of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) archives, for help in making accessible valuable primary source material. Finally, I gratefully acknowledge the support of the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS) and its director, Bernd Kortmann, who kindly allowed me to extend a research fellowship and make use of their excellent facilities during the long months of lockdown in the winter and spring of 2020/21.]

In November 2016, the BBC marked the end of commercial coal mining in the UK by airing the two-part documentary The Last Miners in the primetime slot of 9 pm.1 Masculinity was central to the way in which the filmmakers narrated the story of the closure of Kellingley Colliery in December 2015. As the camera lingered on a frame of the pithead nestled in a semi-rural landscape, a voiceover declared, ›Half a mile under North Yorkshire’s countryside, a rare breed of men are at work […] but not for much longer.‹ Britain’s last coal mine, the viewer learned, was about to close, ›burying a once proud industry‹ and ›terminating the job of every worker‹.2 In a scene below ground, Kevin Rowe, the shift overman and one of the central characters of the documentary, is encouraged by his fellow miners to enter into a rendition of the ›Northern Calypso‹, a self-mocking song that trades in stereotypical images of the coal miner as a whippet-loving, beer-drinking and wife-beating ›big fat Northern bastard‹. To stirring music, supervisor Sheldon Griffin declares that the then Prime Minister, David Cameron, might take their jobs but can never take away their sense of humour. Miners are depicted as tough men, moulded by a lifetime of ›hard graft‹. They form a band of brothers, comradely and loyal, in which shared workplace experiences as well as self-deprecating (and transgressive) pit talk function as social glue. Yet, underneath the tough exterior, miners are shown to be vulnerable, chocked by emotion as the final day of closure arrives. Disorientated by the loss of their natural habitat, they struggle to adjust to an uncertain future above ground: insecure about the transferability of their skills, isolated from each other in their search for work and domesticated as men. As Griffin observes wistfully at the beginning of episode two, looking out of the window of his immaculately clean kitchen, ›There’s only so many times that you can wash the windows, cut the grass, hoover the carpet… I have hoovered twice today, before twelve o’clock!‹3

The documentary sent out an ambivalent message about the miners. While presenting them in a sympathetic light, it also situated them in the past.4 The miners’ modes of sociability and sense of self, no less than the industry in which they worked, were presented as a remnant from a bygone era: quaint, admirable in their own kind of way, but also hopelessly antiquated. In highlighting the miners’ traditionalism, the documentary formed but the latest iteration in a long line of cultural representations that emphasised the structural conservatism of mining communities. In their influential ethnographic study of a Yorkshire mining community in the 1950s, Coal is Our Life, Norman Dennis et al. had depicted ›Ashton‹ (actually, Featherstone) as an occupational community in which all social relations were structured by men’s wage labour in the village pit.5 Gender relations were sharply demarcated, with men expected to bring home the wages and women confined to the domestic sphere, charged with running the household, looking after the children, and providing material and emotional services to their partners. To illustrate the contractual dimension of this relationship, as well as the structural inequality, Dennis et al. detailed the practice of throwing the meal ›to t’ back o’ fire‹, the miner’s customary ›right‹ to indicate dissatisfaction with the cooking by throwing the food into the coal fire and demanding that a new meal be prepared for him.6 Frozen in time, the image of the coal miner as a ›proletarian traditionalist‹ also informed a string of highly influential feature films that were released between the mid-1990s and the mid-2010s, most notably Brassed Off (1996), Billy Elliot (2000) and Pride (2014). All three films invited the viewer to sympathise with the miners’ plight during the 1984/85 coal strike while emphasising that their ideas of manhood were just as antiquated as the industry in which they toiled.7

This contribution is concerned with recovering a different tradition. It seeks to complicate in two ways the image of the miner as a likeable yet hopelessly antiquated underdog, a victim of his own traditionalism just as much as of inevitable socio-economic change. First, by focusing on the British coal industry’s short-lived yet significant ›new dawn‹ of the 1970s and early 1980s, rather than the aftermath of the 1984/85 coal strike, this contribution re-establishes coal miners as powerful (and morally complex) collective agents. Their ›industrial muscle‹ inspired awe and fear, rather than pity, among Britain’s political elites. Second, the contribution shows that masculinity was important to the miners’ collective agency. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) extolled a sense of manhood that the theoretical literature tends to label as ›hegemonic‹ or ›muscular‹: it privileged physical strength and risk-taking, powerful oratory and direct action, disdain for book learning, and irreverence for established authority.8 The NUM’s conception of manhood could lay claim to rest on dual foundations. While having grown ›organically‹ out of shared all-male workplace experiences down the mine, it also incorporated aspects of the rebellious youth (sub-)cultures of the 1960s and 1970s. In this homo-social group, full-time officials were more than mere bureaucrats or functionaries; they were charismatic leaders whose ties with the ›rank and file‹ were affective rather than formal.9 A shared sense of struggle against an Other, who was conceptualised as the class enemy, provided cohesion and direction.10

While much of the literature emphasises the ›dysfunctional‹ aspects of hegemonic masculinity – indeed, in many respects, masculinity as a field of study grew out of a political project that sought to overcome received ideas of manhood –, this contribution highlights a different potentiality.11 It shows how mining trade unionism mobilised conceptions of muscular masculinity to champion progressive causes and further social justice.12 Such a perspective is indebted to the theorising of Stuart Hall and associates at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, who famously identified subcultural practices of male working-class youths as ›rituals of resistance‹ in the context of Britain’s changing social class structure of the 1970s.13 The NUM used their ›industrial muscle‹ to intervene on behalf of ethnic minorities and workplace rights for women. Male strength was, potentially, a resource that could be deployed to usher in a world in which equal rights pertained to all workers, regardless of their gender or ethnicity. Yet, the miners’ mobilisation of male power yielded ambivalent results. It did not go uncontested in the British labour movement either, as the investigation will show.14

The article proceeds by looking at three case studies. Part one examines the NUM’s support of (mostly) female South Asian strikers at the Grunwick Processing Laboratories Ltd in Willesden, North West London, in the summer of 1977. While rationalised as an act of solidarity with a less powerful section of the working class, the NUM’s stance was also part of a broader campaign against ›racialism‹ in late 1970s’ Britain. Part two looks at the NUM’s mobilisation of gendered ideas of struggle during the 1984/85 miners’ strike. Muscular masculinity was invoked as an ideal to bolster the confidence of rank-and-file activists and assert authority over recalcitrant members of the union. Part three explores a feminist critique of the miners’ embrace of muscular masculinity. Socialist feminists came to regard as wrongheaded the labour movement’s infatuation with the coal miner as the embodiment of the ›essential man‹ and class warrior. Other critics objected to what they took to be the sexist objectification of women in the mining union’s own publications. The article concludes by thinking about the relevance of the miners’ experience for the historical exploration of working-class masculinities. The following reflections are based on a wide if admittedly eclectic source base: they comprise uncatalogued archival material from the NUM’s central office in Barnsley; the NUM’s official minutes and conference reports; the miners’ press and selected national press reporting; Coal Board recruitment material and Government reports; autobiographical material and artistic representations of the miners’ strike of 1984/85.

1. The Strutting Miner:

Masculinity and the Protection of Workers’ Rights

In the second half of the 1970s, British mineworkers enjoyed higher status and prestige than at any time since the early 1950s.15 The oil price shock of 1973 had led to an improvement of the market position of coal in relation to crude oil. Meanwhile, predictions of an impending world energy crisis made policymakers rethink the value of coal as a domestic source of energy. After all, coal was available in huge quantities and could be mined independently of shifts in geopolitical relations. More specifically, the national coal strikes of 1972 and 1974, resulting in power cuts and the declaration of a state of emergency, had reminded the public just how essential the mineworkers’ labour still was to the functioning of British society. Collective action, built on the values of workplace solidarity and community cohesion, had humiliated the Conservative government of Edward Heath and contributed to a return of a Labour government in the general election of February 1974. It had also brought tangible material gains, re-establishing miners at the top of the wage league for manual workers. As part of the strike settlement, an agreement was reached between the National Coal Board (NCB), the mining unions, and the Government. Plan for Coal held out the promise of a prosperous future for the industry well into the twenty-first century.16 Among the Left, the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974 had also resurrected a heroic imaginary that viewed mineworkers as the Praetorian guard of the organised labour movement. A New Left Review editorial from 1975 may serve to illustrate this point. The editors hailed the ›audacity and the courage of the miners‹ while being awestruck by their ›intransigent pursuit of proletarian class interests‹ such as had not been witnessed in many decades.17

In the late 1970s, the miners’ collective voice, as articulated through their trade union, mattered politically as well as socially. The deliberations of the NUM at their annual delegate conferences in July were covered extensively in the media and watched anxiously by Governments. National and regional miners’ leaders such as the NUM national president, Joe Gormley, the Communist leader of the Scottish miners, Michael McGahey, and the young Yorkshire firebrand Arthur Scargill became household names.18 As Gormley joked at the 1977 annual conference when handing over a signed copy of the official history of the miners to the Mayoress of North Tyneside, who had welcomed the miners to Tynemouth on behalf of the Metropolitan Council, ›It’s signed by myself, Mick and Lawrence, which after all, is worth a lot of money, because one of my signatures is worth four Rod Stewart’s. You didn’t know that did you? That is the going price at the moment. (Laughter)‹19

Conference resolutions on wages and conditions in the industry had an impact on the stock exchange and the value of Sterling;20 they were deemed important indicators of the Labour government’s ability to maintain its ›social contract‹ with the trade unions, on which its claim to govern better than the Conservatives rested. Times Labour correspondent Paul Routledge’s despairing comment in late 1977 illustrates well the miners’ status and relevance. Referring to the possibility of a new round of industrial action in the coal industry, he reflected wistfully on the preparations for a lavish Mining Festival to be held at the seaside resort of Blackpool to mark the 30th anniversary of the nationalisation of the industry, ›[The first mining festival] is billed as the social event of the year, with more fireworks on Guy Fawkes day than the Queen had for her jubilee celebrations. If events follow the precedent of recent years, it will be fireworks for the miners, and candles for the rest.‹21

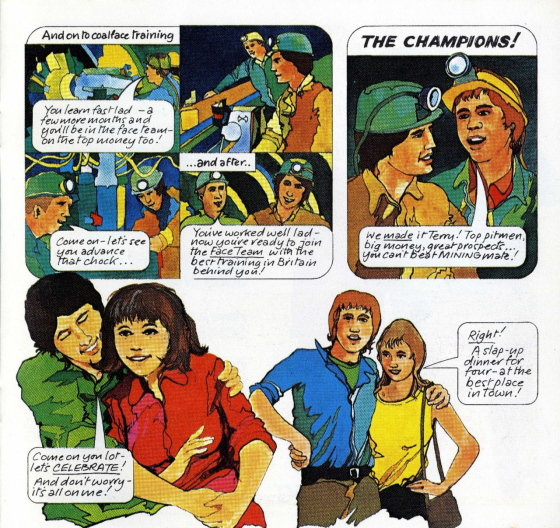

Images of coal miners in the 1970s were more self-consciously gendered than had been the case in the past. Against the context of greater participation of women in paid employment as well as a structural shift to service sector employment,22 the coal industry, in which women were barred from working underground, could be understood as an anomaly.23 Furthermore, despite the introduction of apprentice schemes in the 1960s, the coal industry remained an employer where physical strength and on-the-job skills, rather than formal qualifications, were valued.24 In their recruitment material of the mid-1970s, the National Coal Board aggressively targeted young men by promising them high wages and job security. This was a ›man’s industry‹ for ›men with spirit and initiative who want to develop worthwhile skills‹. While machine powered, men would get to use their muscles too.25 A worthwhile job for life beckoned because, after all, ›people will always need coal‹, as a television advertisement for the South Wales Area put it.26 The recruitment material also emphasised the male friendship and comradery that work in the industry offered, together with the ability to lead a life of hedonistic pleasure that would make, or so the material suggested, the young miner especially attractive to the opposite sex. The TV advertisement included a still image of an indoor swimming pool in which a coal miner was about to be joined in the water by a young woman dressed in a bikini. Another recruiting leaflet, using a comic strip aesthetic to underline its modernity, showed on its front page a miner on a motorbike with a girl seated behind him, with her arms firmly slung around the miner’s hips.27 The leaflet tells the story of young ›lads‹ Mike and Terry, who are impressed by the modernity of the working environment they encounter on a school trip to a coal mine. When they learn that mining is a ›tough job with plenty of responsibility – a team job with everyone pulling their weight‹, in which you earn a ›first-rate man’s wage‹, they sign up with the Coal Board. With their coal face training completed in no time, the two adolescent boys become ›top pitmen‹ who make ›big money [with] great prospects‹. The final cartoon shows them taking their girlfriends out for dinner – ›at the best place in town‹.

On behalf of the NUM, president Joe Gormley articulated a vision of the future in which every miner would share in the material abundance of industrial modernity while remaining at the apex of the patriarchally structured family, at least for the present generation: a nice house, a good education for the children, ›a Jaguar at the front door to take him [i.e., the miner] to work and a Mini at the side to take his wife shopping‹.28 In reality, among miners too, female employment had risen substantially since the 1950s, so the image of the domestic housewife captured only a partial reality.29

Whatever the social reality of gender relations in coalfield communities, the NUM espoused a self-assured muscular masculinity. This identity rested on the confident belief that miners were special and were recognised to be special by others. Miners were special because of the arduous and dangerous nature of the work in which they were engaged; they were also special because of the unique social relations of trust, comradeship and loyalty that informed the political culture of mining trade unionism. The miners’ sense of manhood was tied up with their social class identity. In an age where social class seemed ever harder to define but in which many intellectuals were fascinated by ideas of ›the working class‹ and ›class struggle‹, the miners represented the real thing.30 As miners’ leaders never tired of reminding middle-class theorisers, they had no need to turn to books to find out about either the working class or socialism. They only needed to look at themselves in the mirror. ›You cannot imagine experience. You have to experience experience‹, as Gormley pithily expressed this sentiment.31 The miners tapped into a reservoir of heroic images of manual labour that hailed from the 1930s and 1940s.32 Theirs was not the alienated labour of the automotive assembly line worker; nor did they resemble the atomised youth that John Lennon had immortalised in his famous song Working-Class Hero (1970). Miners were self-assured, essential to the economy and powerful: As an internal Government memorandum noted despairingly in 1981, ›the fact remains that miners are seen to be (and most people with any direct contact would say they are) the »salt of the earth«‹.33

Muscular masculinity was mobilised, in the first instance, against other men, be they managers who knew nothing of ›hard graft‹ or intellectuals who theorised the class struggle without ever having done, or so it was assumed, a day of real manual labour in their lives. The NUM was rooted in regional coalfield communities, but as an organisation, it was outward-looking and internationalist, seeing itself as a champion for social justice around the world. The confident belief to represent real manliness in a patriarchally structured but increasingly feminised society was one of the foundations of a programme of political action that stood up for struggling ethnic minorities and the workplace rights of female workers and oppressed working people everywhere.34 While the NUM as a whole was internationalist in outlook, support for minority causes was championed in particular by the Left or militant wing of the union.35 To an extent, the embrace of progressive causes was an instrument in the internal power struggle with the ›moderates‹, who, in the late 1970s, still retained a structural majority on the union’s decision-making body, the National Executive Committee. It was also a means to cultivate the image of miners as awe-inspiring ›folk heroes‹ among the broader labour movement.

This was the context for the NUM’s intervention in the industrial dispute at the Grunwick photo-processing plant, a medium-sized company located in the Brent district in north-west London, where 137 mostly female workers of South Asian origin (out of a total workforce of 490) had gone on strike over workplace grievances in late August 1976.36 After walking out, the permanent staff among them joined the Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff (APEX) to represent them in negotiations with the company. Upon the advice of the union’s local organiser and the sectary of the District Trades Council, the participants elected a strike committee and began producing a strike bulletin. The strikers were promptly dismissed by the company, with termination of employment notices going out on 2 September. The dispute thus turned into a struggle over the right of workers to be represented by a trade union for collective bargaining purposes. As Linda McDowell, Sundari Anitha and Ruth Pearson have shown, 41-year-old Jayaben Desai became the public face of the strike, with the media drawing frequent attention to her ›exotic‹ dress and otherness from the typical industrial worker and trade unionist.37 When the company’s managing director, George Ward, himself of South Asian origin, refused to recognise the legitimacy of the strikers’ demands, APEX appealed for support from other trade unions.38 At a speech at the Annual Trades Union Congress on 7 September 1976, APEX general secretary, Mr Grantham, established a link between trade union recognition and racial discrimination, arguing that the dispute represented ›a clear case of a reactionary employer taking advantage of race and employing workers on disgraceful terms and conditions‹.39 He urged the labour movement to support the strikers in their demands to secure ›the basic rights that all of us expect‹.40 At the 1977 Annual Congress, Grantham repeated the request for support, emphasising the ›vulnerability‹ of the strikers on account of their history of immigration. He demanded that the labour movement help them secure the same rights that trade unionists in Britain had enjoyed for 100 years.41

The Yorkshire Area of the NUM, alongside South Wales, Scotland and Kent, responded to the call despite reservations that they held about the trade union at the centre of the dispute due to the latter’s lack of support for the miners in 1972 and 1974. As a Yorkshire Area circular made clear, ›In deciding on the Picket, Council Meeting has reached its decision on the point that this is a Trade Union Membership issue and should not be clouded by the fact that APEX is involved.‹42 On 23 June, and again on 11 July 1977, thousands of miners descended upon the capital to reinforce the picket lines outside the factory gates and join with other trade unionists in a Day of Protest and Demonstration. On 23 June, Yorkshire Area president Arthur Scargill was among the miners arrested in scuffles with the police.43 Writing in the Yorkshire Miner, an eyewitness offered a vivid description of the atmosphere in which the miners embarked on the Day of Protest and Demonstration ›to show their support for the oppressed Asian strikers at the Grunwick photo-processing plant‹.44 ›We gathered at midnight outside the N.U.M. offices in Barnsley, many were laughing and joking, some were slightly drunk and it had the atmosphere of a club trip. […] The busses arrived and the men boarded their allotted numbered bus. Still the gaiety was maintained with the bus drivers themselves joining in. Suddenly a cheer went up, and a chant began. »Arthur Scargill walks on water«, it echoed from throat to throat and reverberated from bus to bus, over the craning heads of fellow passengers you saw the familiar pointed face […] of the miners’ president. He went to each bus in turn and held court, his departing joke of »If you get locked up before me I shall complain« repeated again and again.‹45

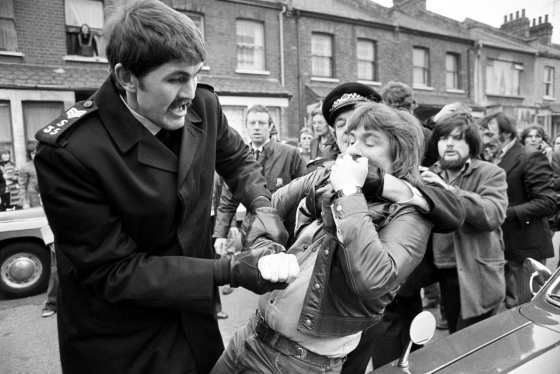

The atmosphere was crackling with excitement and tension, longing for physical release by engaging the police in a ritualised push and shove outside the factory gates, ever ready to descend into fistfights and other forms of physical scuffles. This was ›muscular masculinity‹ on the move, flexing its muscles. As the above ›idealistic witness‹ related the event, ›We lined up on the pavement outside the plant, hemmed in by the massive blockade of blue with welded arms and blank official expressions. »Polite« banter ran up and down the line but all stood still suddenly, no-one knew why or who [sic], a movement began near the gates, a solid wall of pickets moved forward relentlessly forcing the line of police towards the entrance, like an onrushing tide this movement spread across the whole line and advice and advice echoed through the street, we were winning. […] Pickets sweated, policemen sweated, and respect for both sides was forged in the rising body heat.‹46

Grunwick Laboratories was an intensely physical affair.

This press photograph was taken on 23 June 1977.

(picture-alliance/dpa/empics)

The presence of female pickets was noted by some miners. In their accounts, references to ›girls‹ served to underline the observation that the police had broken the unwritten rules of engagement. They had escalated the push and shove into an all-out street fight that deliberately sought to cause bodily harm and showed no respect either to the wounded nor to female pickets. As the eyewitness above related the scenes outside the factory’s second entrance, ›Here we found a completely different story, as each picket was wrenched and dragged from the line he was punched and kicked to the ground, pulled to his feet and flung into the waiting coaches. We saw their pain-wracked faces through the steel barred windows. We saw young girls pummelled by these blue coated protectors, we saw one man pulled into the open area, held by two bastions of law and order whilst another hit him with the point of his helmet, gashing the side of his head open […].‹47 Another miner, writing in the activist paper The Collier, also referred to the violence and sexual harassment suffered by women as a particularly egregious illustration of the police’s abrogation of the unwritten rules of engagement.48

Admiring accounts of the miners’ display of collective strength outside the factory gates of Grunwick were not confined to the miners’ own publications. Nor was the underlying perception that the miners were a special breed of men. In Grunwick. The Workers’ Story, Jack Dromey, secretary of the local Trades Council and a key protagonist in the dispute, paid special tribute to the miners. Under the headline ›Enter the miners‹, Dromey praised the miners as ›the toughest and most militant section of the British working class‹. In glowing terms, eerily reminiscent of inter-war Fascist propaganda, he celebrated the miners as an awe-inspiring disciplined formation, irresistibly powerful, ›The Yorkshire miners […] registered an immediate impact on all spectators. Women with shopping baskets and local workers out for a lunch-time stroll stared in total silence as the miners’ delegation approached. They marched in grey and brown working clothes, with open-necked shirts, not in groups, but in a solid line of powerful arms that stretched from pavement to pavement without a break. There were no placards, no banners, no hurry and no lingering, just a solid impenetrable mass of grim determination.‹49

Mass picketing in the summer of 1977 helped turn what had been a local dispute into an event of national significance. On 11 July 1977, as many as 12,000 trade unionists assembled outside the company’s gates while 20,000 joined the march through London.50 Only when the miners and other trade unionists got involved did the strike action by the Grunwick employees, which had been going on since August 1976, turn into a major political and media event. The House of Commons debated the dispute three times in June 1977 alone.51 ›Grunwick‹ became a cause célèbre for both the radical Left and the radical Right, with the centre-left Labour government under Jim Callaghan desperately trying to defuse a potentially explosive situation by launching a Court of Inquiry and other initiatives at arbitration.52 The price, however, of the miners’ (and other trade unionists’) intervention was high: The problem was not so much that the Day of Action of 11 July failed, as had previous mass pickets, in closing down the factory. Under police protection, the employees still at work managed to enter the premises, and vital chemicals and other supplies to the company were not cut off. Rather, the problem was that questions of picket-line violence and disorder came to displace the workplace grievances and the issue of trade union recognition, just as the figure of Jayaben Desai mounting a lonely picket was displaced by miners’ leader Arthur Scargill marching at the head of massed columns of mainly male (and white) trade unionists. Indeed, the question of the miners’ involvement stood at the centre of disagreements between the national leadership of APEX and the local strike committee. Whereas APEX president Grantham declared publicly in early July that the union intended ›to reduce the temperature‹ and ›did not want a thousand Yorkshire miners here because they will not assist in the resolution of the dispute‹, the strike committee welcomed the miners’ support.53 Inside the NUM, too, the miners’ action was not welcomed by all. At the NUM’s annual conference at the beginning of July, national president Joe Gormley appealed to all areas to coordinate their solidarity action with APEX as the union that was officially in charge of the dispute, rather than bypass them. As Gormley was probably well aware, the militant areas of Yorkshire, Scotland and South Wales chose to ignore this advice.54 Even among Scargill’s own power base in Yorkshire, some miners thought that the NUM’s involvement in other workers’ struggles far away from the coalfields was misplaced. As an older miner from Barrow Colliery near Barnsley told a journalist in November 1977, ›Our Arthur […] shouldn’t go down to bloody Grunwick and show himself off. […] They don’t want him, and his job’s up here.‹55

At Grunwick in 1977, the miners mobilised muscular masculinity as a resource to support other workers in their struggle for workplace rights. Did the strikers’ gender and ethnicity matter to the NUM? The union’s own records contain remarkably few reflections on this point. What appears to have mattered was the Grunwick strikers’ identity as workers rather than their sex or ethnicity. The NUM supported the mostly female South Asian workers in their struggle just as they would have supported male workers in other industries, in steelmaking, in the docks or on the railways. While such gender-blindness may easily be interpreted as a sign of the NUM’s deliberate or unconscious refusal to recognise their own ›privilege‹ as (mostly) white men, a remarkable piece published in the Derbyshire Miner in April 1982 opens up the possibility of a different reading.56 The article reported on the recent visit to Britain of Mary Zinn, a US American female face worker. (In the United States, unlike Britain, women were not legally barred from working below ground in a mine.) The writer observed that ›most of [the media coverage] dealt with her as a women [sic] – little about her as a miner. Yet when she came to the Derbyshire NUM to meet full-time officials […], it was the second characteristic that proved most interesting.‹ From the perspective of the NUM, social class identity, rather than gender, provided the basis from which to construct a politics of progressive advance.

2. Wolves and Scabs:

Masculinity and the Limits of Power

Whereas in 1977 the miners had deployed their industrial muscle in support of (mostly) female strikers in the photo-processing trade, in 1984, they mobilised their strength in defence of their own livelihoods and communities. The Great Miners’ Strike of 1984/85 was called in response to the National Coal Board’s plan for restructuring the industry through cutting output, closing 20 pits and reducing the number of men on colliery books by 20,000 in the financial year 1984/85.57 The NUM suspected, correctly, that the proposed reduction was only the beginning of a much more far-reaching process that, according to the union’s estimation, would entail the cutting back of the coal industry to a ›profitable‹ core of 100 units and 100,000 men, reducing the industry to almost half its size within five years.58 From the beginning, all sides in the conflict invested the dispute with broad symbolic significance. The coal strike came to be seen as a political confrontation between organised Labour and the neoliberal state, the decisive battle for the future of Britain that had been anticipated ever since the formation of the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher in May 1979.59

Yet the dispute was, in fact, a complex affair, pitting coalfield against coalfield and miner against miner no less than miners against the employer and miners against the state.60 With the election of Arthur Scargill as Gormley’s successor to the post of national president in December 1981 and Peter Heathfield’s election as general secretary in March 1984, all three NUM national officials were for the first time in its history of the Left. Together with the NUM’s vice-president, veteran Communist leader Mick McGahey, they would form a ›troika‹ during the strike. Controversially, the NUM relied on spreading the strike through direct action ›from below‹ rather than by calling a pithead ballot of all members, as had been done in 1972 and 1974 (and on many other occasions). At the NEC meetings of 8 March and 12 April 1984, the Left leadership outflanked the moderate opposition and declared as official the stoppages in the areas. The executive decision was sanctioned retrospectively by a Special Delegate Conference on 19 April 1984.61 The idea was to create a domino effect by which reluctant coalfields and collieries would be brought into line. For the success of this strategy, the NUM relied on the commitment and direct action of an activist core of committed trade unionists, which comprised about 10,000 men, roughly 5 per cent of the overall membership.62 The strategy resulted in bringing production to a halt, in the spring, at circa 140 collieries (out of a total of 185), but it failed to unite all NUM members behind the industrial action.63 The crucial Nottinghamshire coalfield continued working almost normally throughout the strike, with Nottinghamshire miners abetted by a massive police presence in their daily crossing of NUM picket lines.64

Throughout the conflict, the NUM mobilised ideas of masculinity to galvanize the membership into action and shame non-striking miners. The conflict was conceptualised as a crucial test in which a miner’s real character was revealed. Deeds counted more than words, and the present more than the past or the future. Muscular masculinity was not an attribute that miners possessed on account of their sex; it was an ideal that miners were enjoined to live up to. Real miners and, by implication, real men were expected to subordinate short-term personal interests to the general interest as defined by the NUM. In this crucial ›battle‹, they were expected to forego their obligations to their families in favour of loyalty to their union, community and social class. To an extent, the martial rhetoric was metaphorical, but only to an extent. The NUM expected their members to become actively involved; to be prepared to put their bodies on the line in physical confrontations with the police; to risk physical injury, police arrest and a criminal record (leading to dismissal) in pursuit of the strike. In return, they were offered an exhilarating collective experience, a sense of personal dignity and a place in History.

It was a cohort of young activists who were held up by the NUM as a shining example to others, the real backbone of the strike and the Union’s future. In his contribution to the Extraordinary Annual Conference, held in Sheffield on 11-12 July 1984, veteran miners’ leader Mick McGahey praised this cohort as ›my young wolves‹, who were out there ›barking‹ and ›fighting‹; ›proud young men and their womenfolk‹. With men such as these, even the general strike of 1926 could have been won. This was why, in McGahey’s estimation, 1984 was ›the most wonderful strike‹ he had ever been in. The ›young wolves‹ were brave, committed, with no time for procedural niceties – ›he is not going back, and you can ballot until you are blue in the face‹, as George Bolton, born in 1934, exclaimed at the Special Conference on 19 April with reference to his younger brother, who was one of the pickets. The activists had no qualms about imposing their will on the waverers and the undecided, if necessary, by physical force. McGahey admitted as much when he added wryly, ›I would hate to be a scab, and how a scab must hang his head in the face of those young wolves‹. In doing so, McGahey hinted at the polar opposite to the young activists. In this imaginary, anyone who violated the sacred principle of trade unionism – the refusal to cross an official picket line – placed himself outside of the community of miners: he was a traitor to the union, the community and himself, unworthy to be called a miner. He was also unworthy to be called a man: ›scabs‹ were not men; they possessed neither honour, guts, nor spine.65 Kent miners’ leader Jack Collins expressed this duality in uncompromising terms. Speaking at the Special Delegate Conference on 19 April 1984 that sanctioned the union’s strike strategy, he exclaimed, ›I am proud of those lads who have been on the picket line, proud of the comrades who have been sleeping in the buses. […] The rest of you, who have not got the guts to stand by men like that ought to hang your heads in shame. (Hear, hear) Hang your heads in shame. Don’t call yourselves colliers. (Applause)‹66

As the strike dragged on into the summer and autumn of 1984, the dispute turned into a ›war of attrition‹ between striking miners and the state. The conflict pitted two different types of endurance against each other: the miners’ ability to withstand material hardship against the government’s ability to provide an uninterrupted supply of electricity to the public. In this context, the NUM came to foreground a different dimension of muscular masculinity, the ability of miners to withstand individual suffering for the greater cause. As Arthur Scargill declared at the Labour Party Conference in Blackpool on 1 October 1984 to standing ovations from the delegates, ›We have suffered attacks on the picket line from a state police force armed in full riot gear – state violence against miners. (Cheers and applause) We are suffering hardship at the present time bearing in mind that their [sic] only crime is fighting to save our industry, our jobs in the mining communities.‹67

To be able to withstand police violence and the ability to see one’s own family suffer hardship came to define the measure of a miner’s manhood. It was through their suffering that the miners were ennobled. Miners did not suffer just for themselves but on behalf of the entire working class and all working people of Britain. The more they lost in material terms, the greater the example they set for others. As Scargill declared in July 1985 at the first Annual Conference following the organised return to work the previous March, ›We have come through a strike that has changed the course of British history: a conflict of tremendous significance which has resounded around the world […] which has inspired workers in this and other countries to defend the right to work.‹68

The rhetoric of heroic suffering struck a chord with strike-bound coalfield communities. It resonated among the broader labour movement, and to an extent, the general public.69 Through the work of sociologists and social historians, the trope of noble suffering also entered the scholarship on the strike. The work of Raphael Samuel, tutor at Ruskin colleague and an influential figure in the ›history from below‹ movement, performed an important role in this process. His edited collection The Enemy Within. Pit Villages and the Miners’ Strike of 1984–85, published in 1986, may be regarded as a foundational text.70

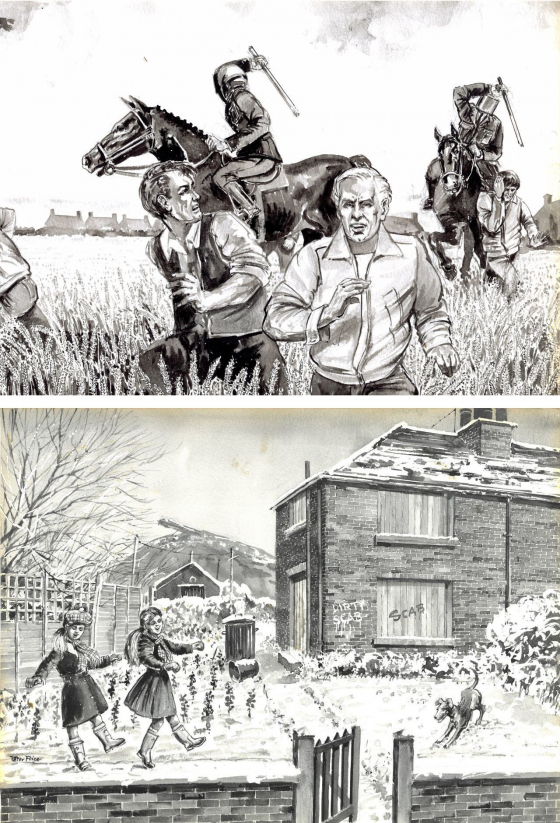

The suffering was real. Yet, there was a more ambivalent, darker side to the spectacle of men being driven to desperation by hardship, which the early scholarship was concerned to de-emphasise.71 As the strike continued and autumn gave way to a long dark winter, the bonds of solidarity between striking miners slowly but inexorably eroded. Quietly, miners slipped away and returned to work, in small numbers at first, but increasingly so as time went on. By November 1984, the stirring rhetoric of the labour movement’s conference season had been exposed as just that, words without consequence. Hope of a settlement became an ever more distant prospect. Desperately trying to stem the tide, strike-bound communities turned against those who had broken ranks. Striking miners resorted to attacks on property, physical assaults and ostracism against their erstwhile colleagues and their families. A cycle of nine drawings from the Yorkshire pit town of Maltby offers a stark interpretation of the strains that the strike imposed on local communities. While some images depict scenes of communal self-help and determination, others show helplessness and powerlessness: mounted police chasing striking miners through a field; men going coal-picking and in search of firewood. Two images illustrate the dialectic of cohesion and ostracism. One painting shows a scene in which two girls, watched over by two adults, shout abuse at another girl and her mother, with the girl crying and the mother with a frozen expression on her face. Another image shows an abandoned property, doors and windows boarded up, with the slogan ›dirty scab‹ graffitied over the property.72

1984/85 coal strike exerted upon the Yorkshire mining community of Maltby.

The ink drawings were made towards the end of the strike or shortly thereafter.

(courtesy of the National Union of Mineworkers)

Jean McCrindle, a lecturer at Northern College in Barnsley and a leading protagonist in Women Against Pit Closures, emphasised this ambivalence in her response to a draft manuscript on the strike that Raphael Samuel had sent her. The draft, she averred, was much too positive. The strike, she emphasised, had been ›painful, difficult and dark‹.73

Just as with the broader community, within the nuclear family, too, material hardship could expose underlying tensions, leading to relationship breakdown and domestic violence, rather than ennoble the sufferer. As a miner who had returned to work in February 1985 wrote in an anonymous letter to Jack Taylor, president of the Yorkshire Area, ›it hurt me starting but I had to. I’ve 3 kids and my wife keeps threatening to leave me I had to start I was destitute.‹74 A 42-year old miner from Horden in Durham, dismissed by the National Coal Board for physical assault, told the journalist Tony Parker how the strike had put additional strain on an already fraught relationship. ›The wife wasn’t sympathetic to the miners and we were always rowing about it: she kept telling me I was a lazy bugger […] and then one day I hit her once too often and she pissed off to her mother’s.‹75 By the spring of 1985, with the number of miners back at work reaching the crucial mark of 50 per cent, area union leaders, although not the national leadership, reached the conclusion that the miners could take no more suffering. To prevent the NUM from disintegrating, the Delegate Conference on 3 March 1985 decided narrowly on an organised return to work without an agreement.76 This way, it was hoped, the miners would salvage a moral victory from a crushing industrial defeat with their dignity intact. They had stayed true to themselves, as good trade unionists and loyal miners, and also as men. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that even the miners who had not stayed out until the end accepted a moral framework according to which the morally superior action would have been to stick it out.77 The strike breakers’ return to work was, at best, excusable given desperate circumstances. All the same, it was a moral blemish that they would carry with them for the rest of their lives.

In the NUM’s conceptualisation, women could show themselves to be morally superior to men. Throughout the conflict, the NUM leadership went out of its way to praise strike-supporting women as a crucial pillar of the conflict. ›There are no words from this Union that can adequately describe the courage and strength and the solidarity of our members or the Women’s Support Groups, who are now part of this Union‹, Scargill declared at the Special Delegate Conference in March 1985.78

On this understanding, the women who were active in the support movement had revealed all the qualities that the non-striking miners lacked: they were courageous, determined and strong, standing ›shoulder to shoulder‹ with the striking miners.79 In the crucible of the strike, their consciousness had been transformed. Ordinary miners’ wives left behind the domestic sphere and abandoned the housework and the telly in order to join their men in the public arena. Not only did they staff the communal food kitchens, but they also went on marches, spoke at public rallies and confronted the police on the picket line. ›We are women, we are strong / We are fighting for our lives / Side by side with our men / Who work the nation’s mines / United by the struggle, / United by the past, / And it’s – Here we go! Here we go! / For the women of the working class‹, as a popular campaign song of the support movement put it.80

Women Against Pit Closures campaign in 1984/85,

written by Mal Finch

The reality was more complex. As Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Natalie Thomlinson have shown, early post-strike accounts that emphasised the spontaneous nature of the women’s support groups must, in part, be understood as a conscious strategy to obscure the important role that the NUM leadership played in fostering the support movement.81 The heroic narrative of ›never the same again‹, emphasising the transformative nature of female activism on coalfield communities, served a similar function.82 In addition to obscuring the prior experience in political campaigning that key protagonists in the support movement possessed, the narrative also mobilised an anachronistic image of gender relations in the coalfields that bore greater resemblance with the sociological findings of the 1950s than with the social world of the 1980s. In fact, as Jim Phillips has shown with reference to the Scottish coalfields, it was precisely because many female members of miners’ households were in paid employment that Scottish miners were able to maintain the strike for so long.83

3. Yesterday’s Men:

Muscular Masculinity and the Feminist Gaze

Both in 1977 and 1984/85, the NUM mobilised a conception of muscular masculinity to confront other men, the police in 1977, and the police and sections of the union’s own membership in 1984/85. To be a miner and a trade unionist was also to be a real man, understood as the ability to translate the rhetoric of class struggle into action; to sacrifice immediate self-interest for the greater good; to be prepared to put your body on the line in pursuit of the goal of a better society for all. During the same period, however, the miners’ own practices came under scrutiny. Questions were raised about misogynist elements in the miners’ and the union’s conception of masculinity. These concerns were indicative of the growing influence of feminism on the public debate among the Left in the 1970s and 1980s.84 British second-wave feminists inhabited the same political world as the miners, if not exactly the same social milieu. Indeed, the conceptual armoury of a feminist critique of contemporary society – including the ideas of ›patriarchy‹, ›masculinity‹ and not least of all, ›gender‹ itself – began to gain wider currency during the period.85 The debate on the miners related both to presentational matters and social practices. Internally as well as publicly, critical voices were raised about the use of female models in the union’s own publications, in particular The Yorkshire Miner. In the aftermath of the strike, other critics argued that the very image of the miner as ›the essential man‹ had helped to weaken the strike. To these critics, the cult of masculinity that had been built up around the miner illustrated a broader problem in the British labour movement. It needed addressing if the Left ever hoped to regain the initiative in the confrontation with the forces of Thatcherism.

In the May/June 1977 issue of The Yorkshire Miner, a remarkable letter to the editor appeared. Headlined ›Beauty and the Chauvinist Beast‹, Angela Devaney praised the NUM for the determined stance the union was taking against the re-emergence of organised racism in 1970s Britain.86 The fight against ›racialism‹ showed itself by a policy of zero tolerance towards pit workers who had joined the National Front; by the affiliation of individual union branches to the Anti-Nazi League; and by support for Rock Against Racism, amongst other initiatives.87 Devaney also paid tribute to the labour movement’s support for greater gender equality in British society. At the same time, the letter took strong exception to the use of images of scantily clad female models on page three of The Yorkshire Miner. Devaney demanded a debate about the objectification of women and reduction to their physical attributes. She suspected that the images were included ›for no other reason than to provide a sight for somebody’s sore eyes, or to maintain or increase circulation by pandering to the reactionary views of some of your readers‹. Underlining her mining credentials as a miner’s daughter and one-time miner’s wife, Devaney paid tribute to the NUM as ›among the most far sighted and progressive‹ organisations in contemporary Britain. Precisely because she considered the union an ally for greater gender equality, she felt that their use of sexualised femininity was shocking. She admonished that the use of page-three models constituted ›an example of the most shocking chauvinism and discrimination‹.

Devaney was not alone in taking exception to the practice. In a letter to Yorkshire president Arthur Scargill, Vic L. Allen, professor of sociology at the University of Leeds and long-time supporter of the Left-wing in the NUM, protested in strong terms that one of his historical pieces had been printed side by side with the image of a semi-naked woman. As Allen made clear, the practice was ›degrading to women and offensive to both men and women‹. Just like Devaney, Allen contrasted the union’s active stance against racism with its apparent indifference towards sexism. As Allen emphasised, ›I believe strongly that just as the attitudes of white people must be altered in order to eradicate racism so the attitudes of men must be altered to eradicate sexism. It would be heartening if your paper would take as firm a stand on sexism as it does on racism. It would also be heartening if those who determined your editorial policy could be seen to understand that the economic exploitation of women is similar to the economic exploitation of black people. Your presentation of women as sex objects reinforces the system that creates this exploitation.‹88

In his reply, the Yorkshire miners’ leader defended the decision to print Allen’s piece on page three on practical grounds and simply reiterated that the Union held a different view on the question of page-three pin-ups. Indeed, Scargill, alongside other trade unionists, had long been concerned about the impact of the mass tabloids on the miners’ consciousness and lamented the inability of the labour movement to produce publications that ›ordinary‹ miners would want to read. The inclusion of female models in The Yorkshire Miner, alongside punchy headlines, was seen as a means to increase the popularity of the paper among the workforce and the broader working class. Thus, the perpetuation of chauvinistic ideas was seen as a price worth paying for raising the members’ awareness of their class identity.

While critics such as Devaney and Allen contended that the miners did not take female objectification seriously enough, others held that the real problem went deeper than the use of sexualised imagery. The real problem, they held, was the miners’ embrace of muscular masculinity, and by extension, the labour movement’s cult of the miners as men. In her analysis of the coal strike, published shortly after the return to work, Beatrix Campbell observed that the dispute had had a ›peculiarly English tone‹ to it. Campbell equated Englishness with violence: ›Violence […] is enclosed within an English culture that once ruled the world by brute force, it’s there in the celtic twilight of our colonies, it appears on the terraces and playing fields of England. It is a peculiarly masculine characteristic. Which perhaps explains the tendency of the male left to equate »muscular militancy« and violence with political strength. While not necessarily condoning crass violence, it has shown plenty of sympathy with »the lads«.‹89

›Muscular militancy‹ had dominated the tactics of the NUM, and the ›male left‹ had mistaken picket line violence for political strength. In criticising the NUM’s reliance on mass picketing, Campbell aligned herself with an analysis that was articulated by the Eurocommunist wing of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It found expression in the pages of the party’s influential theoretical journal, Marxism Today.90 The critique was expounded most fully in a pamphlet drafted by Pete Carter, the CPGB’s industrial organiser.91 In short, the Eurocommunists held that the miners should have capitalised on the burgeoning support movement for the strike – on developing a cross-class rainbow coalition of community groups, the Churches and minority rights groups – rather than relying on ›traditional‹ trade union support and prioritizing mass picketing.

Campbell, however, gave this critique a feminist twist. In doing so, she built on her earlier work on the ›cult of masculinity‹ that, in her estimation, had dominated the labour movement’s infatuation with the miners for far too long. As Campbell had written in Wigan Pier Revisited, her adaptation of George Orwell’s classic interwar travelogue to the conditions of the 1980s, ›The socialist movement in Britain has been swept off its feet by the magic of masculinity, muscle and machinery. And in its star system, the accolades go to the miners – they have been through hell, fire, earth and water to become hardened into heroes. […] Miners are men’s love object. They bring together all the necessary elements of romance. Life itself is endangered, their enemy is the elements, their tragedy derives from forces greater than they, forces of nature and vengeful acts of God. That makes them victim and hero at the same time, which makes the[m] irresistible – they command both protection and admiration. They are represented as beautiful, statuesque, shaded men.‹92

At Grunwick, and later in support of striking hospital workers, the miners had posed as ›gladiators for women‹, but according to Campbell, this had veiled ›their reservations about the rights of women in general, which have been entrenched in the culture of their community‹.93 The problem was thus two-fold: of social being and of representation. It resided in the social relations of mining communities and in the celebration of muscular masculinity as a progressive force. Although the research for Wigan Pier Revisited was carried out before the onset of the miners’ strike – the book contained vivid descriptions of miners’ rallies in 1982 – Campbell’s critique developed traction in the changed conditions of the post-strike environment: As the Labour Party embarked on its journey of ›modernisation‹ and the trade unions embraced a ›new realism‹, the miner was transformed from an archetypal heroic man into a broken man. Instead of awe and fear, miners came to inspire sympathy and pity. Above all, they were seen to represent the past; they were admirable in their own kind of way, but ›completely out of touch with the modern world‹, as Tony Blair was to put it in his autobiography.94

In today’s political discourse, an overt display of masculinity is often seen as irreconcilable with the support of progressive causes. Indeed, across the liberal press, social media and Higher Education settings, it has become customary to prefix the term with the adjective ›toxic‹.95 Unreconstructed masculinity is presented as one of the major obstacles on the forward march towards a society that celebrates diversity. In the 1970s, there existed, albeit for a short period, the possibility of a different future. The British coal miners used masculinity to further the workplace rights of women and to combat racialism. In the wake of the oil crisis and two successful strike actions, the miners had been reconceptualised as a vanguard in the labour movement’s struggle for a society in which the same rights pertained to anyone regardless of their gender or ethnicity. The New Left activist and social historian E.P. Thompson hailed the miners as the embodiment of a vernacular tradition of English radicalism. Writing at the height of the 1972 strike, he proclaimed, ›[The miners] came, at first, as ambassadors of a past culture, reminding us of whom we once were. They remained to challenge us as to whom we might yet become.‹96 Other observers were more guarded in their praise. While acknowledging the NUM as a force for progressive change, they highlighted the problematic aspects of the miners’ activism. Feminists critiqued the miners’ embrace of sexualised popular culture. They also drew attention to the union’s disregard for the structural inequalities that existed inside coalfield communities and the British labour movement.

The miners’ sense of manhood was inextricably linked to their social class identity, and as the controversy over the use of sexist imagery revealed, miners’ leaders were prepared to tolerate sexism to heighten the social class identity of their members. Whereas in 1977 the miners deployed their ›industrial muscle‹ in support of marginalised workers, in 1984 miners mobilised muscular masculinity in defence of their own livelihoods and communities. As the miners’ resistance was slowly eroded in a long ›war of attrition‹ with the Conservative government, their gender identities were called into question alongside their social class identities: While eliciting admiration for their capacity to withstand hardship, the miners’ aspirations came to be re-interpreted as a ›last stand‹ in a doomed defence of an outmoded way of life. ›Muscular‹ strength became a problem, rather than part of the solution, in the Left’s vision of a better future. Beatrix Campbell’s characterisation of the miners as ›Clark Gables of class struggle‹, penned shortly before the 1984/85 strike, encapsulated this reconceptualisation well: Just like Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind, the miners represented a lost cause.97

Much of the historical scholarship has followed rather uncritically in the wake of popular culture. It has adopted an image of miners as the traditionalist embodiment of a fast-fading industrial age. In his celebrated account of post-war Europe, first published in 2005, Tony Judt characterised the British miners as a ›doomed community of industrial proletarians‹, while Avner Offer, in a landmark article on manual labour, denoted the 1984/85 strike as ›the proletarians’ last stand‹. In a more popular register, Graham Stewart has labelled the British miners of the 1980s as ›the real conservatives‹.98 More recent interventions have sought to carve out a different path. They have been concerned to rediscover the forward-looking aspects of coal mining culture and mining union politics: the communitarian self-help traditions; their understanding of economic and social processes in ›moral economy‹ terms; most of all, perhaps, their reconciliation of a place-based identity with an internationalist outlook, rooted in a class-conscious universalism.99

In its concern to rediscover roads not taken, the present contribution situates itself within this broader research endeavour.100 Above all, however, it has been concerned, to quote from E.P. Thompson again, to take the miners seriously ›in terms of their own experience‹.101 When Margaret Thatcher infamously labelled the striking miners the ›enemy within‹ during the height of the coal strike, she paid them a backhanded compliment.102 As Britain’s first female Prime Minister was all too aware, the miners possessed collective agency. They used their power in morally complex terms, furthering as well as dismissing as trivial the concerns and life chances of societal groups less well organised than themselves. Posterity’s condescension can come in many forms, and as Thompson knew, judging historical actors by the standards of our present is one of them.

Notes:

1 The Last Miners, Episode One, dir. Wes Pollitt, 21:00, 21 November 2016, BBC1 London, 60 min; Episode Two, 21:00, 28 November 2016, BBC London, 60 min (forthwith: Last Miners, Two). For a discussion of the cultural representation of the closures of Kellingley and the challenges for historical scholarship, see Jörg Arnold, ›Like Being on Death Row‹: Britain and the End of Coal, c. 1970 to the Present, in: Contemporary British History 32 (2018), pp. 1-17.

2 Last Miners, Two, available to watch at <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kTF2caDbbmU>.

3 Ibid., at 1:57-2:08.

4 See Gerard O’Donovan, The Last Miners is a Moving Meditation on the Fate of the Kellingley Colliery: Review, in: Telegraph (online edition), 21 November 2016: ›What definitely did not emerge, however, was an image of a modern, efficient industry that might have had a future, save for political interference.‹

5 Norman Dennis/Fernando Henriques/Clifford Slaughter, Coal is Our Life. An Analysis of a Yorkshire Mining Community, London 1956; 2nd ed. 1969, reprinted 1971, 1974, 1976, 1979.

6 Ibid., pp. 180-182.

7 For a discussion, see Cora Kaplan, The Death of the Working-Class Hero, in: New Formations 52 (2004), pp. 94-110; Alan Sinfield, Boys, Class and Gender: from Billy Casper to Billy Elliot, in: History Workshop Journal 62 (2006), pp. 166-171; Diarmaid Kelliher, Thoughts on »Pride«: What’s Left Out and Why Does it Matter?, 7 October 2014, URL: <...> [no longer available]; see also Jörg Arnold, The British Miner in the Age of De-industrialisation. From Loser to Winner and back again (Routledge, forthcoming), chapter 8. Brassed Off is set during the 1992/93 coal crisis, rather than in 1984/85, but the great miners’ strike is central to the plot.

8 John Tosh, Hegemonic Masculinity and the History of Gender, in: Stefan Dudnik/Karen Hagemann/John Tosh (eds), Masculinities in Politics and War, Manchester 2004, pp. 41-58, here p. 47; Ava Baron, Masculinity, the Embodied Male Worker, and the Historians’ Gaze, in: International Labor and Working-Class History 69 (2006), pp. 143-160, here p. 146.

9 Olmo Gölz, Helden und Viele – typologische Überlegungen zum kollektiven Sog des Heroischen: Implikationen aus der Analyse des revolutionären Iran, in: helden. heroes. héros 7 (2019), pp. 7-20; English translation: Heroes and the Many: Typological Reflections on the Collective Appeal of the Heroic. Revolutionary Iran and its Implications, in: Thesis Eleven 165 (2021), pp. 53-71.

10 Arthur Scargill/Peggy Kahn, The Case for Conflict, in: New Society, 7 January 1982, pp. 9-10.

11 John Tosh, The History of Masculinity: An Outdated Concept?, in: John H. Arnold/Sean Brady (eds), What is Masculinity? Historical Dynamics from Antiquity to the Contemporary World, London 2011, pp. 17-34, for the quotation p. 19; R.W. Connell, The Big Picture: Masculinities in World History, in: Theory and Society 22 (1993), pp. 597-623, here p. 603: ›In relation to masculinity it defines the enterprise as one of »studying up«, a matter of studying the holders of power in gender relations with a view to informing strategies for dismantling patriarchy.‹

12 Baron, Masculinity (fn 8), p. 146.

13 Stuart Hall/Tony Jefferson (eds), Resistance through Rituals. Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain, New York 1975, 2nd ed. Abingdon 2006.

14 Nick Owen, The British Left and the ›indignity of speaking for others‹, unpublished paper delivered at a workshop on ›Contracting Horizons‹ at the University of Nottingham, 17 January 2015.

15 Tony Garnett, Working in the Field, in: Sheila Rowbotham/Huw Beynon (eds), Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, London 2001, pp. 70-82, here p. 79: ›When Arthur Scargill was strutting with his hubris after the famous victory over Heath at Saltley coke plant, Ridley was quietly preparing his plan to destroy the miners.‹ I have developed this point more fully elsewhere. See Jörg Arnold, Vom Verlierer zum Gewinner – und zurück: Der Coal Miner als Schlüsselfigur der britischen Zeitgeschichte, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 42 (2016), pp. 266-297.

16 The essential documents are: NCB, Plan for Coal, London 1974; Department of Energy, Coal Industry Examination. Interim Report June 1974, London 1974; Department of Energy, Coal Industry Examination. Final Report 1974, London 1974; Department of Energy, Coal for the Future. Progress with ›Plan for Coal‹ and Prospects to the Year 2000, London 1977. On the energy crisis of the 1970s, see Historical Social Research 39 (2014) issue 4: The Energy Crises of the 1970s, ed. by Frank Bösch and Rüdiger Graf; on the politics of the NUM, Andrew Taylor, The NUM and British Politics, vol. 2: 1969–1995, Ashgate 2005. For Britain in the 1970s more generally (including a discussion of the 1972 and 1974 strikes): Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out. Britain in the Seventies, London 2009; Lawrence Black/Hugh Pemberton/Pat Thane (eds), Reassessing 1970s Britain, Manchester 2013.

17 New Left Review 92 (1975), editorial; Vic L. Allen, The Militancy of British Miners, Shipley 1981.

18 Down to Earth: A Story of Coal and Colliers, Part 2, written and produced by Ralph Bernard, Independent Radio (1979), URL: <http://bufvc.ac.uk/tvandradio/lbc/index.php/segment/0031800070001>.

19 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1977, London 1978, p. 334.

20 Miners’ Vote Halts Advance of Pound and Causes Sharp Drop in Share Prices, in: Times, 2 November 1977.

21 Paul Routledge, On Collision Course now as the Miners Plunge the Pay Policy into Darkness, in: Times, 2 November 1977.

22 Duncan Galley, The Labour Force, in: A.H. Halsey/Josephine Webb (eds), Twentieth-Century British Social Trends, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 284-323.

23 See Mines and Quarries Act 1954, Part VIII, § 124 (1): ›No female shall be employed below ground at a mine.‹ URL: <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Eliz2/2-3/70/part/VIII/enacted>.

24 Avner Offer, British Manual Workers: From Producers to Consumers, c. 1950–2000, in: Contemporary British History 22 (2008), pp. 537-571, here pp. 538-539.

25 NCB, Man Miner … gets a lot out of a career in coal, undated (late 1970s/early 1980s).

26 NCB, People will always need coal (1975), URL: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILJkgbq9gJM>.

27 NCB, Get it all together as a skilled miner. Produced by Colbear Advertising in conjunction with NCB Public Relations (c. 1975).

28 Joe Gormley, Battered Cherub. The Autobiography of Joe Gormley, London 1982, p. 186.

29 Jim Phillips, Scottish Coal Miners in the Twentieth Century, Edinburgh 2019, p. 62 (with reference to Scotland); Lutz Raphael, Farewell to Class? Languages of Class, Industrial Relations and Class Structures in Western Europe since the 1970s, in: Benjamin Zachariah/Lutz Raphael/Brigitta Bernet (eds), What’s Left of Marxism. Historiography and the Possibilities of Thinking with Marxian Themes and Concepts, Berlin 2020, pp. 265-290, here p. 285; Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, ›Reopen the Coal Mines‹? Deindustrialisation and the Labour Party, in: Political Quarterly 92 (2021), pp. 246-254, here pp. 250-252.

30 Raphael, Farewell to Class? (fn 29), p. 273 (on the revival of languages of class in the 1970s).

31 Gormley, Battered Cherub (fn 28), p. 194.

32 Huw Beynon, Images of Labour/Images of Class, in: Rowbotham/Beynon, Looking at Class (fn 15), pp. 25-40. For context: Jörn Leonhard/Willibald Steinmetz, Von der Begriffsgeschichte zur historischen Semantik von ›Arbeit‹, in: Leonhard/Steinmetz (eds), Semantiken von Arbeit. Diachrone und vergleichende Perspektiven, Cologne 2016, pp. 9-59.

33 Policy Unit, The NCB/NUM Problem, 22 May 1981, p. 4, The National Archives (TNA), PREM 19/540, URL: <https://331215bb933457d2988b-6db7349bced3b64202e14ff100a12173.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/PREM19/1981/PREM19-0540.pdf>.

34 Stuart Hall, Brave New World, in: Marxism Today, October 1988, pp. 24-29, here p. 24 on the ›feminisation‹ of the workforce in late twentieth-century Britain.

35 For the various political factions inside the NUM see Paul Routledge, Why Miners look to the Left Wing for Leadership, in: Times, 3 January 1974; Newcomers Who Hardened the Miners’ Line, in: Times, 4 January 1974; Why the Moderates of the NUM are Behaving less Moderately, in: Times, 7 January 1974.

36 The best factual account remains the report by the official court of inquiry set up by the Secretary of State for Employment on 30 June 1977, Report of a Court of Inquiry under the Rt Hon Lord Justice Scarman, OBE into a Dispute between Grunwick Processing Laboratories Limited and Members of the Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff (Cmnd. 6922), London 1977. See also Jack Dromey/Graham Taylor, Grunwick. The Workers’ Story, London 1978; Joe Rogaly, Grunwick, Harmondsworth 1977; Jack McGowan, ›Dispute‹, ›Battle‹, ›Siege‹, ›Farce‹? – Grunwick 30 Years on, in: Contemporary British History 22 (2008), pp. 383-406; Linda McDowell/Sundari Anitha/Ruth Pearson, Striking Narratives: Class, Gender and Ethnicity in the ›Great Grunwick Strike‹, London, UK, 1976–1978, in: Women’s History Review 23 (2014), pp. 595-619.

37 McDowell/Anitha/Pearson, Striking Narratives (fn 36), pp. 607-611.

38 Report of a Court of Inquiry (fn 36), pp. 5-11.

39 TUC, Report of 108th Annual Trades Union Congress, London 1976, pp. 466-467, here p. 466.

40 Ibid.

41 TUC, Report of 109th Annual Trades Union Congress, London 1977, pp. 398-399, here p. 398.

42 B.S. Circular, 29 June 1977, in: N.U.M. Yorkshire Area, Minutes for the Year 1977, Barnsley 1977, p. 423.

43 Rogaly, Grunwick (fn 36), p. 179.

44 Ben Toomer, A Time for Marching and a Time for Picketing, in: Collier, July 1977.

45 Grunwick Picket, from an idealistic witness, in: Yorkshire Miner, August 1977, p. 4.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 John Fox, [no title,] in: Collier, August 1977.

49 Dromey/Taylor, Grunwick (fn 36), pp. 123, 146.

50 Ibid., p. 144.

51 On 20 June, 23 June and 30 June 1977, respectively.

52 McGowan, ›Dispute‹ (fn 36), p. 384.

53 Dromey/Taylor, Grunwick (fn 36), p. 140.

54 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1977 (fn 19), p. 413.

55 Corinna Adam, Miners and Misunderstandings, in: New Statesman, 11 November 1977, pp. 643-644, here p. 644.

56 Miner Mary, in: Derbyshire Miner, April 1982, p. 4. On the emergence of ›privilege‹ as an analytical category: Peggy McIntosh, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, in: Peace and Freedom, July/August 1989, URL: <https://psychology.umbc.edu/files/2016/10/White-Privilege_McIntosh-1989.pdf>.

57 The literature on the strike is vast, but remains very much wedded to the battlelines drawn up in 1984. For a good overview, see Arne Hordt, Von Scargill zu Blair? Der britische Bergarbeiterstreik 1984–85 als Problem einer europäischen Zeitgeschichtsschreibung, Frankfurt a.M. 2013. For a comparative perspective, see Arne Hordt, Kumpel, Kohle und Krawall. Miners’ Strike und Rheinhausen als Aufruhr in der Montanregion, Göttingen 2018.

58 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1984, Sheffield 1985, p. 51.

59 Richard Vinen, A War of Position? The Thatcher Government’s Preparation for the 1984 Miners’ Strike, in: English Historical Review 134 (2019), pp. 121-150; Jim Phillips, Containing, Isolating, and Defeating the Miners: The UK Cabinet Ministerial Group on Coal and the Three Phases of the 1984–85 Strike, in: Historical Studies in Industrial Relations 35 (2014), pp. 117-141.

60 David Howell, Defiant Dominoes: Working Miners and the 1984–5 Strike, in: Ben Jackson/Robert Saunders (eds), Making Thatcher’s Britain, Cambridge 2012, pp. 148-164.

61 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1984 (fn 58), pp. 49-55 (8 March), 105-106 (12 March), 109-135 (19 April).

62 This was a government estimate: Minutes of Ministerial Group on Coal, MISC 101 (84), 35th meeting, 30 August 1984, in: TNA, CAB130/1268, f197, URL: <https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/133274>.

63 According to government figures, as of 25 April 1984, 40 collieries were producing normally and some coal was turned at a further 6. See Minutes of Ministerial Group on Coal, MISC 101 (84), 12th meeting, 25 April 1984, in: TNA, CAB130/1268, f61, URL: <https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/133251>.

64 See David Amos, The Nottinghamshire Miners, the Union of Democratic Mineworkers and the 1984–85 Miners Strike: Scabs or Scapegoats?, PhD thesis, University of Nottingham 2012.

65 Phillips, Scottish Coal Miners (fn 29), p. 254.

66 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1984 (fn 58), p. 120.

67 Report of the Annual Conference of the Labour Party 1984, London 1984, pp. 33-35, here p. 34.

68 Presidential Address, 1 July 1985, in: NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1985, Sheffield 1986, pp. 490-496, here p. 491.

69 Michael Jones, Glory to the Tales of Arthur, in: Sunday Times, 7 October 1984, p. 16.

70 Raphael Samuel/Barbara Bloomfield/Guy Boanas (eds), The Enemy Within. Pit Villages and the Miners’ Strike of 1984–85, London 1986. For a fuller discussion see Jörg Arnold, ›The rather Sinful City of London‹: the Coal Miner, the City and the Country in the British Cultural Imagination, c. 1969–2014, in: Urban History 47 (2020), pp. 292-310.

71 Peter Gibbon/David Steyne, Thurcroft. A Village and the Miners’ Strike. An Oral History, Nottingham 1986, preface: ›The aim of the work has been to be both truthful and positive. While not suppressing the bleaker aspects of what happened, we have tried to dwell most on what Thurcrofters saw as being worthwhile and heroic about their struggle.‹

72 At the time of writing, the circle of drawings was on display in the NUM Miners’ Hall, Barnsley.

I would like to thank Paul Darlow for making available digital copies of them to me.

73 Jean McCrindle to Raphael Samuel, 11 June 1986, in: Bishopsgate Institute, Raphael Samuel Archive, RS4/250.

74 Anonymous to Jack Taylor, 27 February 1985, in: NUM Archives, Barnsley, O. Briscoe files.

75 Tony Parker, Red Hill. A Mining Community, London 1986, pp. 85-88, here p. 86.

76 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1985 (fn 68), p. 105.

77 Samuel/Bloomfield/Boanas, Enemy Within (fn 70), pp. 72-77.

78 NUM, Annual Report and Proceedings 1985 (fn 68), p. 102.

79 Jean Stead, Never the Same Again. Women and the Miners’ Strike 1984–85, London 1987, p. 127.

80 Quoted in Patricia Francis, ›We Are Women, We Are Strong‹: Celebrating the Unsung Heroines of the Miners’ Strike, in: Conversation, 9 March 2018, URL: <https://theconversation.com/we-are-women-we-are-strong-celebrating-the-unsung-heroines-of-the-miners-strike-92448>.

81 Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite/Natalie Thomlinson, National Women Against Pit Closures: Gender, Trade Unionism and Community Activism in the Miners’ Strike, 1984–5, in: Contemporary British History 31 (2018), pp. 78-100; Jean Spence/Carol Stephenson, ›Side by Side With Our Men?‹ Women’s Activism, Community and Gender in the 1984–1985 British Miners’ Strike, in: International Labor and Working-Class History 75 (2009), pp. 68-84. See also Sheila Rowbotham/Jean McCrindle, More than Just a Memory: Some Political Implications of Women’s Involvement in the Miners’ Strike, 1984–85, in: Feminist Review 23 (1986), pp. 109-124.

82 The key text is Stead, Never the Same Again (fn 79).

83 Phillips, Scottish Coal Miners (fn 29), pp. 255-256.

84 Pat Thane, Women and the 1970s: Towards Liberation?, in: Black/Pemberton/Thane, Reassessing 1970s Britain (fn 16), pp. 167-186; Lynne Segal, Jam Today: Feminist Impacts and Transformations in the 1970s, in: ibid., pp. 149-166; Natalie Thomlinson, Race, Ethnicity and the Women’s Movement in England, 1968–1993, Basingstoke 2016.

85 Joan W. Scott, Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis, in: American Historical Review 91 (1986), pp. 1053-1075.

86 Angela Devaney, Beauty and the Chauvinist Beast, in: Yorkshire Miner, May/June 1977.

87 On the NUM’s antiracist campaigns, see: Anti-Nazi League News, in: Collier, June/July 1978; see also: We are black most of the time – but our hearts are the same, in: Collier, October 1978, title page; Miners Against the Nazis, in: Collier, November/December 1978. The NUM’s conceptualisation of ›racialism‹ and the extent and limits of their activism merit a separate investigation.

88 Allen to Arthur Scargill, 2 November 1978, NUM Offices, Barnsley, uncatalogued material.

89 Beatrix Campbell, Politics Old and New, in: New Statesman, 8 March 1985, pp. 22-25.

90 Peter Ackers, Gramsci at the Miners’ Strike: Remembering the 1984–1985 Eurocommunist Industrial Relations Strategy, in: Labor History 55 (2014), pp. 151-172.

91 Pete Carter, Coal Pamphlet, second draft, in: People’s History Museum, Manchester, CP/CENT/IND/07/02.

92 Beatrix Campbell, Wigan Pier Revisited. Poverty and Politics in the Eighties, London 1984, p. 97.

93 Ibid., p. 111. See also Judith Hicks Stiehm, The Protected, the Protector, the Defender, in: Women’s Studies International Forum 5 (1982), pp. 367-376.

94 Tony Blair, A Journey, London 2010, p. 42. Blair applied this judgement to the miners’ leadership. He did not explicitly include all miners in this indictment.

95 Maya Salam, What is Toxic Masculinity?, in: New York Times, 22 January 2019. Author’s personal observation from running undergraduate courses on contemporary history at the University of Nottingham between 2013 and 2021.

96 E.P. Thompson, A Special Case, in: New Society, 24 February 1972, pp. 402-404, here p. 404.

97 Campbell, Wigan Pier Revisited (fn 92), p. 98.

98 Tony Judt, Postwar. A History of Europe since 1945, London 2005, p. 542; Offer, British Manual Workers (fn 24), p. 544; Graham Stewart, Bang. A History of Britain in the 1980s, London 2013, p. 345.

99 Phillips, Scottish Coal Miners (fn 29); Diarmaid Kelliher, Making Cultures of Solidarity. London and the 1984–5 Miners’ Strike, London 2021.

100 Emily Robinson et al., Telling Stories about Post-war Britain: Popular Individualism and the ›Crisis‹ of the 1970s, in: Twentieth Century British History 28 (2017), pp. 268-304, here p. 277. For the European dimension of the structural changes driving this process: Lutz Raphael, Jenseits von Kohle und Stahl. Eine Gesellschaftsgeschichte Westeuropas nach dem Boom, Berlin 2019.

101 E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, New York 1963, new ed. London 2013, p. 8 (online edition).