For millions of disabled people around the world the wheelchair has been one of the most important technological innovations of the twentieth century. From its inception as a relatively cumbersome, heavy machine, designed principally for indoor use, the wheelchair has evolved into a sophisticated and highly technical mode of transport. Wheelchairs are, at least in the Global North, relatively widely used and universally recognizable – so recognizable that they have become the cultural symbol to represent all disabled people.1 Wheelchairs are often viewed with trepidation: as machines that disable, confine, and deprive their occupant of independence – as medical devices that doctors prescribe only to the sick, the wounded or the elderly. Such definitions and perceptions infiltrate the public lives of wheelchair users, cause considerable macro2 and micro3 political difficulties, and consequently disable users in a myriad of different ways.

The idea of wheelchairs as medical devices contributed to the structural exclusion of wheelchair users, entrenching the belief that wheelchair use outside of the medical domain was abnormal. This led to a lack of understanding on the part of agencies that supply wheelchairs and companies that manufacture them about how they were actually used, and the failure of architecture and town planning to account for wheelchair use.

For people who use wheelchairs, however, they are tools of independence that enable their inclusion. They allow users to participate in and be informed about public life, and are tools of political activism.4 Without the modern wheelchair there would have been no liberation of disabled people as we know it, and whilst there is a danger of slipping into the language of technological determinism, its effects on the development of disability politics have been substantial.

(Wikimedia Commons, Hans Peters/Anefo, Lichamelijke gehandicapten houden protesttocht in Amsterdam tegen hoge stoepen e, Bestanddeelnr 925-8875, CC0 1.0)

My contribution surveys this disconnect through an exploration of a century of tension between two broad social processes that have dominated the topography of wheelchair history: the medicalization and the politicization of wheelchairs and wheelchair users. The article uses mainly data from the United Kingdom and North America and draws on a tradition of historical sociology, which at its most basic asks questions about social processes over time and attends to the interplay of action and structure to make sense of individual and social transformations.5 My aim is to show not only that wheelchairs are tools of independence, enabling the inclusion of disabled people, but that they are also political machines.

1. Wheelchairs as Medical Devices

The European origins of wheelchairs as medical devices probably date back to the mid-seventeenth century with the first recorded use of ›mechanical invalid chairs‹ by sick, injured and/or disabled people. By the late eighteenth century, the status of wheelchairs as medical devices was reinforced as various machines began to appear in surgical and medical instrument catalogues as vehicles to transport patients.6 Among the violent consequences of two world wars was an intensification of the enrolment and mobilization of medical professionals by states across Europe and North America to act as gatekeepers to state provision for disabled veterans,7 which further advanced a hegemony that classified disability as a medical condition and consequently defined the wheelchair as a medical device. As the state became involved in the supply and provision of wheelchairs, it also legitimized the medical control over the technology.8

in a new hospital for paraplegics at Isleworth, 1949

(British Pathé, Film ID: 2278.07)

Paradoxically, though, medical/rehabilitation ideology and practice has long interpreted wheelchair use as a sign of failure.9 With its concentration on the cure or alleviation of impairment, rehabilitation contributed to what it meant to be ›able-bodied‹ with a focus on ›returning to a prior situation‹.10 This notion of normalcy and its strong association with the medical-industrial construction of disability developed in earnest following the two world wars. The initial goal of rehabilitation through technology was to reconstruct and reintegrate maimed veterans into the industrial body, into the productive social machinery: to make disabled people able, and useful to both state and society.11 Wheelchair use symbolized either the failure of medicine to find a cure, and/or that the wheelchair user had given up on rehabilitation: it was the ›duty‹ of disabled people to adjust themselves to society.

A clear example of this ideology is given in an article written in 1949 by Professor Donald Munro, one of the founders of the modern concept of spinal cord injury rehabilitation,12 on the attitudes of the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA): ›If it is worth while trying to rehabilitate paraplegics at all, it is worth doing it in such a way as to give them as close approximation to normalcy as it is possible to obtain. […] I am in grave doubt whether or not your organization has this point of view. […] I do not know your officers personally but were I an officer representing your Society I would be ashamed to be photographed for publicity purposes sitting in a wheelchair. […] Why be represented by an admission of failure? Why not have the courage to live greatly and make the symbol what it ought to be – calliper braces or crossed crutches inside a laurel wreath? What moral cowardice to miss such an opportunity to demonstrate to all the world that nothing short of full accomplishment will satisfy[,] even symbolically, the will to succeed.‹13

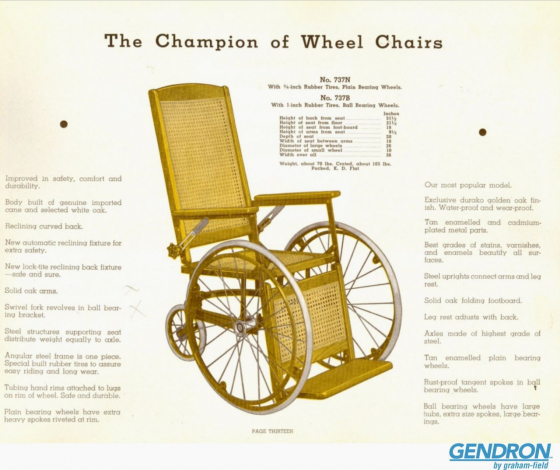

Wheelchairs then were seen as machines designed to transport a ›patient‹ from one place to another, usually within the confines of an institution. Those designs on offer in medical appliance catalogues during the 1930s and 1940s differed little in configuration from those on offer at the end of the nineteenth century, although wire-spoke wheels and rubber tyres (borrowed from the bicycle) were two important innovations introduced. Few wheelchairs facilitated independent mobility outdoors, and for those designs that did allow for some sort of independent mobility, the implicit assumption was that the user would be housebound or institutionalized. Nearly all occupant-propelled wheelchairs had the propelling wheels situated at the front and the castor/s at the rear, the advantages of which were better manoeuvrability in tight spaces and the means to go straight through a doorway without having to first line up: criteria best suited for indoor use. Outdoors, however, front-propelling wheels were useless. The rear castor/s made it impossible to tip and balance these types of wheelchair. This prevented progress up kerbs or up/down steps, and because most were non-folding, they were largely incompatible with other forms of transport.14

advertisement from Gendron Company wheelchair catalogue, ca. 1937–1945

(Courtesy of <https://gendroninc.com>; see also

<https://www.utoledo.edu/library/virtualexhibitions/dvx/ctrpc_gendron.html>)

Throughout the history of wheelchairs, it is clear that the state and its agents, architects, town planners, designers and managers of transport systems incessantly misunderstood the issue of wheelchair access, or actively resisted its implementation. In Britain in 1957, for example, when confronted with the problems faced by disabled people travelling to and from a place of employment, the Ministry of Labour and National Service suggested that: ›employers should allow disabled staff to leave a few minutes early so that they could be the first in the bus queues‹.15 When asked to provide kerb ramps to facilitate the crossing of roads, in 1958, the Highways Division responded: ›You will appreciate that the proportion of wheeled pedestrians is tiny. […] Accordingly, we have to balance any advantage to the few against any disadvantage to the many. Such disadvantage is the absence of the »step off«, separating the safe from the danger areas. We need some very positive dividing lines to save the jay-walkers and dreamers.‹16

Indeed, the low number of disabled people visible in public was a common excuse for the denial of wheelchair access. In discussions on the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Bill about access to public transport, the National Bus Company claimed in 1971 that disabled passengers were: ›[A] relatively small part of the totality of bus passengers [and as such, it] would be unrealistic to expect operators to provide special facilities which could cost them money and would be unlikely to increase demand.‹17

Similarly, in the US the National Capital Transportation Agency claimed in 1965 that it was ›technologically infeasible and economically insane‹ to make the then proposed Washington DC subway accessible to wheelchair users.18 The American Public Transport Association (APTA) also fiercely fought Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act (part of which required mass transit companies to make new buses accessible), claiming in 1983 that there were too few disabled people to benefit from accessible buses, because the majority of them could not get to bus stops in the first place. Occasionally such arguments bordered on the ridiculous. When confronted with pressure to not discriminate against wheelchair users wanting to fly, the US Airlines Pilots Association and the Airlines Stewardesses Association demanded in 1973 that every flight carrying a wheelchair user ›must be met by rescue, fire and ambulance equipment on the runway‹ and that a ›Red Cross should be painted‹ at wheelchair evacuation points.19 But there is, as already argued, an alternative reading of the wheelchair, one that sees it as a tool of independence and agency.

2. Wheelchairs as Political Instruments

The accepted understanding of the development of disability politics locates the political response to the issues of access and with it the politicization of disability in the late 1960s and 1970s.20 However, whilst it is the case that the last quarter of the twentieth century witnessed a groundswell of political activity, it is also apparent that the politics of wheelchair access has a longer history. There have been three distinct political responses, although each response overlaps.

Phase 1: 1900–1951. Derek Seaton’s study of the history of the Leicestershire and Rutland Guild of Disabled People shows clearly a realization in the early 1900s that the provision of wheelchairs and spinal carriages was key to the encouragement of its members to retain their independence.21 Indeed, when the Guild drew up its list of general rules in 1910, the first objective was to provide its members ›with necessary spinal carriages, bath chairs, or crutches, and to keep the same in repair‹.22 The years following the First World War witnessed a large increase in the Guild’s membership, and its policy of wheelchair supply did increase the visibility of disabled people in Leicester. But as the following quote from Seaton’s history of the Guild highlights, it also emphasized the rarity of such provision elsewhere: ›»Why are there so many cripples in Leicester?« This was a question which was frequently asked by visitors to the town, when they saw so many disabled people in spinal carriages and Bath chairs in the streets. Some could barely recall seeing anyone in a spinal carriage in their own cities or towns, whereas in Leicester they were encountered frequently.‹23 By the 1930s, the Guild’s attention shifted away from the provision of wheelchairs to the search for cures and the establishment of an orthopaedic clinic.

In the US, wheelchair access was also an important issue for the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation. The Institute was founded in 1927 by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the eventual President of the United States, who worked closely with architect Henry Toombs during the early 1930s to create an accessible environment for wheelchair users with poliomyelitis through the amalgamation of a number of innovations such as non-slip surfaces, automatic doors, ramps and specifications for ramp gradients. The Architectural and Mechanical Hints Group of the National Patients’ Committee soon promoted Toombs’ work and incorporated his ideas into their political campaign to make all public buildings accessible to disabled people.24

While innovations at Warm Springs promoted and demonstrated the possibilities of disability access, it is clear that the expectation was still that wheelchairs would ›normally be pushed by attendants‹.25 At the rehabilitation/education program at the University of Illinois, however, the notion of independence went further than access to the physical environment. For Professor Timothy Nugent, who started the program in 1947, independence was not only the end goal, it was also the central tenet. The prevailing ethic at the University of Illinois was that disabled people had to be prepared to deal with whatever they encountered in society. So, while Nugent ensured that almost every building on campus was ramped and accessible, and provided a fleet of buses equipped with hydraulic lifts to convey disabled students to their classes, he would only admit wheelchair users who could function independently: that is, without the aid of an attendant. Students had to be physically fit, able to transfer on and off their wheelchairs and able to push their wheelchairs over long distances, even through the snow. Nugent’s equation of physical fitness with independence manifested itself most clearly in his emphasis on wheelchair sports as an important part of the training program. It was also apparent in his refusal to allow powered wheelchairs on campus.26

The University of Illinois program advanced the necessity of wheelchair access and indeed influenced many other universities and colleges to follow in its path. But as former disabled student Mary Lou Breslin (cofounder of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund at Berkeley) recalled, politically its notion of independence remained relatively antiquated: ›Then later, when I began to think about and understand my own experience a bit more, I thought about the [University of Illinois], and I thought that they should have – as an academic institution – done better. They should […] not have permitted this patriarch [Nugent], this fanatical person to determine and direct so many people’s lives. […] [N]obody ever said, »Let’s start to think about disability as a political issue. Why is it that the Rehab Center is promoting its philosophy that if you can’t get in the building you should crawl up the steps? That’s your personal responsibility, and unless you’re willing to make that commitment, you can’t come to school here.« There’s something really radically sick about that picture. […] [T]he people who needed attendants were cut off at the knees and never got in to begin with. [...] So they would really pick and choose – you were penalized if you were very disabled. It was sick; the whole selection process was sick.‹27

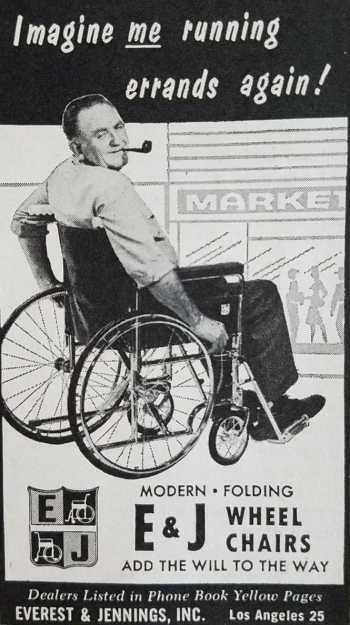

Phase 2: 1951–1968. The emergence in the 1950s of relatively lightweight folding wheelchairs and developments in powered wheelchairs, however, brought with them the possibility of independent mobility within the community.28 With these new technologies, physical access to the built environment and with it the possibility of independent living increasingly became political issues. Two organizations of disabled people, the Invalid Tricycle Association (ITA) in Britain and the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA) in the US, both gradually developed a political interest in wheelchair access from the early 1950s and both to some extent shaped the disabled people’s movement’s response to discrimination, laying the foundations for what Michael Oliver was later to call the Social Model of Disability.29

The commencement of the ITA’s access activism coincided with the 1951 Festival of Britain. The building of a number of the New Towns was already underway and the Festival provided an opportunity to promote contemporary ideas in architecture. For the ITA, 1951 marked the point when ›vast numbers of disabled people should be considered as being citizens worthy of such architectural consideration as will make their lot a little less difficult, whether it be in connection with a town hall, a public library, a village hall, theatre or cinema.‹30

Although not the primary focus of their political activities, the possibility of influencing change to the built environment gradually developed within the ITA. By 1965, now renamed the Disabled Drivers Association (DDA), it re-examined its role and incorporated the right to access public buildings as a major part of its political struggle.31 One of the factors influencing this shift of emphasis was the visit in 1962 by Professor Timothy Nugent. Invited by the Central Council for the Disabled, he presented a lecture to the Royal Institute of British Architects on The Elimination of Architectural Barriers to the Physically Disabled. Nancy Bull, a regular commentator in the DDA’s publication, The Magic Carpet, attended the lecture and described its impact as giving her ›an entirely different slant on the whole idea of disability‹ and a realization that ›society must give us the conditions wherein we can help ourselves‹.32

Nugent had been one of the leading figures in the promotion and drafting of the American Standard Specifications for Making Buildings and Facilities Accessible to and Usable by the Physically Handicapped, approved by the American Standards Association (ASA) in October 1961.33 The ASA standards had grown out of a long campaign by various groups of and for disabled people, including the PVA, which had begun its access activism in 1955 in response to Hugo Deffner’s campaign to eliminate all steps in public buildings.34 By 1959, the PVA and other campaigning groups persuaded the President’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped and the National Easter Seal Society for Crippled Children and Adults to commission the ASA to provide standards to ensure that access for physically disabled people was included in the construction and renovation of all public buildings and facilities. The President’s Committee and Easter Seals also established two committees, a Steering Committee under the directorship of Nugent and a Sectional Committee made up of representatives from professional and trade associations, societies, and government agencies, to tackle the problem of architectural barriers. These committees’ findings and the ASA standards eventually influenced the passing of the Architectural Barriers Act 1968, which marked one of the first US efforts to ensure access to the built environment. However, the Act was mostly ineffectual largely because there were no enforcement mechanisms and compliance was at best inconsistent.35

In Britain, the Joint Committee on Mobility for the Disabled (JCMD) and the Central Council for the Disabled joined the DDA in its campaign for better access. Spurred on by ›successes‹ in the US, a similar strategy of advocating building standards took hold. In 1963, the Central Council for the Disabled asked the British Standards Institute (BSI) to set up a committee to draft a code of practice on accessibility to public buildings, the result of which was The British Standard Code of Practice CP 96, Access for the Disabled to Buildings, Part 1: General Recommendations, published in 1967.36 The disabled architect Selwyn Goldsmith also published his book Designing for the Disabled (1963). The outcome of a meeting in 1961 between the Polio Research Fund, the Building Exhibition and the Royal Institute of British Architects, Goldsmith wrote the book as a design manual and it was the first in Britain to look at access issues in all buildings, rather than simply hospitals, residential homes and rehabilitation centres.37 Goldsmith was among the first to claim that the disadvantage experienced by disabled people was not the result of their impairment, but was rather the result of the way society is organised, writing: ›Many disabled people […] are handicapped socially and economically because architectural barriers prohibit them from obtaining easy access to public buildings. […] Complete rehabilitation and reintegration in society is often difficult for the individual to achieve because the individual is prevented by architectural barriers from participating in normal situations of employment or education to which he is suited.‹38

Nancy Bull described the book as revolutionary, and Goldsmith himself became an influential figure in access design.39 However, at this time the politics of disabled access in Britain remained relatively conservative in its approach and outlook, as is apparent in O.A. Denly’s (President of the DDA and Chair of JCMD) description of it to the Architectural Association in 1967: ›The whole history of the accessibility campaign in this country has been a matter of education, encouragement and example. It is unlikely, in my opinion, to differ in the future.‹40

In this prediction, Denly was wrong: principally because, as in the US, the strategy was largely ineffectual. Despite the passing in the UK of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970, which included provisions to encourage ›reasonable‹ adjustments to facilitate access for disabled people, along with numerous campaigns, such as the Silver Jubilee Committee 1977, which aimed to create greater public awareness of access problems, discrimination against disabled people remained widespread.41

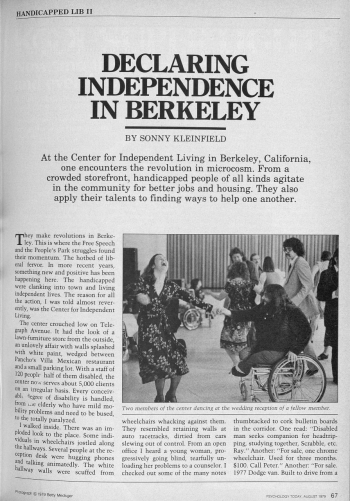

Phase 3: 1968–2001. Towards the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s, the disabled people’s movement in general and the campaign for wheelchair access in particular adopted a more radical approach. Influenced by the cause of the civil rights movement and the tactics of the student, free speech and anti-war movements, all prevalent in California throughout the 1960s and 1970s, disabled students at Berkeley came to understand their own social circumstances as an effect of discrimination and an absence of civil rights. This shift in thinking and the political conditions within which it germinated centred California as the US capital of disability protests.42 Although disability activists in Berkeley maintained elements of the moderate approach in that they aimed to work with city and transport authorities, they developed in parallel a more militant approach where activists were prepared to file law suits and demonstrate to gain access rights.43 The movement at Berkeley was important at this time, not necessarily because the people there or the tactics they used were the most radical, but because their successes turned Berkeley into a ›Mecca for anyone who had mobility issues‹.44

In his 1979 book The Hidden Minority.

A Profile of Handicapped Americans,

the journalist Sonny Kleinfeld reported on the Center for Independent Living, which had been founded in 1972. An extract from this book was published in the popular magazine Psychology Today in August 1979. See also the rich documentation and contextualisation at <https://revolution.berkeley.edu/projects/place-every-body/>.

As highlighted above, when the Physically Disabled Students’ Program (PDSP) developed its concept of independent living it became clear that it had to reconfigure not only social arrangements, but also technological ones. Wheelchair design was an important element in the realization of independence, but equally important was the necessity to reconfigure the user environment. To this end the PDSP and later the Center for Independent Living (CIL) accomplished a great deal in a relatively short timeframe. In 1969, the first incarnation of the PDSP, the Rolling Quads, convinced city authorities to install kerb ramps during their rebuild of Telegraph Avenue. The PDSP expanded its goals for the removal of architectural barriers and continued to exert political pressure on both city and university authorities by means of negotiation and forms of protest. Initial successes in 1971 and 1972 included the establishment of the Coordinating Committee for the Removal of Architectural Barriers within the university, which drew on internal expertise to identify and remove architectural barriers from the campus, and the passing of a resolution within the city council to make all street corners accessible by installing kerb ramps.45

Indeed, the campaign to install kerb ramps throughout the city was so successful and political action within Berkeley so vibrant that an urban myth grew around their origin. The legend involved Eric Dibner (Advocate and Specialist in Architectural Accessibility) and Hale Zukas (National Disability Activist in Architectural and Transit Accessibility and in Personal Assistance Services) both going out in the middle of the night and using jackhammers or nitroglycerine to blow up kerbs and then with cement or asphalt create their own kerb ramps.46 As with many legends, some real actions and events lie behind them. Dibner did recall ›creating‹ some kerb ramps, but the tale was rather more modest: ›That was a little later when Ed [Roberts] asked for some ramps to be – there were some corners where he had problems going from his house to CIL, or maybe it was the Disabled Students’ Program. So, I got a bag of cement and went out. They were real low curbs, like a couple of inches, at Dana and Dwight, probably at Ellsworth and Dwight, and I think I did one at Ellsworth and Blake. It was just to bevel the corner. I mean, we didn’t build curb ramps, we just put some cement down to make it useable.‹47 The contribution of Zukas, in addition to his political activities, was in designing a kerb ramp that the city then used for almost a decade before they adopted the national standard.48

A particular focus of the movement’s concern with access was on public transportation. Again, California led the way with the opening of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) in 1972, which according to Harold Wilson, a wheelchair user and consultant on the BART program, was the ›first rapid transit system in the world to offer 100 per cent usability‹ to disabled people.49 As Wilson emphasized at the time: ›Accessible transportation is often the deciding factor between being dependent on society, friends, or family and being independent within society. I’ll never forget that sense of freedom I experienced boarding a BART test train for the first time.‹50

Although not entirely accessible, BART was nonetheless unique.51 All other transport systems either ignored or actively resisted the necessary changes required for use by disabled people, especially after the passing of the Rehabilitation Act 1973 and the subsequent blocking of Section 504, which would make discrimination against disabled people by any program or organization that received federal funding illegal. Although this would include a welter of services, activists within the CIL focused their attention on transport because, as Kitty Cone (Political Organizer for Disability Rights, 1970s – 1990s, and Strategist for Section 504 Demonstrations, 1977) recalled: ›We felt that it was very, very important, because if you didn’t have the transportation component the people were going to be really hamstrung. They wouldn’t be able to function freely in their communities, they wouldn’t be able to get to their jobs, education and services. It was absolutely critical to have transportation. The transportation issue was always the hardest fought issue. It was always the issue where money was raised, where the opposition got the most support. It was sort of ironic, because we thought it was so similar to – we weren’t sitting in the back of the bus; we weren’t even sitting on the bus.‹52

In a similar vein to the PDSP and the CIL, the Atlantis Community in Denver, founded by Wade Blank and Glenn Kopp in 1975, evolved from a client-controlled service provider for disabled people into the most preeminent US disability protest organization of the 1980s: the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT). Atlantis began their protest in 1978, when demonstrators took over buses in Denver’s rush hour to protest at the lack of accessible transport. An eventual victory in 1982 (the Regional Transit District in Denver procured new accessible buses and retrofitted its existing fleet with chair lifts) spurred the organization to go national in 1983 with the formation of ADAPT. Civil disobedience and confrontational tactics were favored by ADAPT. They would block buses, occupy the hotels where the American Public Transit Association held conferences, aim to get arrested, and arrive in communities in advance of any protest to train local people in their tactics. ADAPT also targeted both government and companies. For example, they held numerous protests against the Greyhound Bus Company, many of which were coordinated nationally. One such protest was on 9 August 1997, when protesters gathered in forty cities across the country to block Greyhound buses. Initially resistant, the Greyhound Bus Company eventually gave in to ADAPT’s demands and equipped their buses with wheelchair lifts in 2000.53 None of this activity would have been possible without the emergence of new, lighter or more mobile wheelchairs, both in the manual and powered versions.54

Wheelchair design and the politics of wheelchair access are inextricably linked. Changes in wheelchair design simultaneously developed from and were catalysts for the demand for greater access to the built environment. Wheelchairs, both as physical objects and as cultural symbols, shaped disability politics, which in turn reshaped wheelchairs and the legislative responses that have restructured our communities and buildings to incorporate wheelchair use. As agents of both social and technological change, disabled people not only redefined the meaning of disability and began a movement that changed the meaning of disabled people’s independence. They also furthered a material, political and ideological reinterpretation of what wheelchairs are and what they should do. Reinterpreted as tools of independence, as opposed to medical devices, wheelchairs became instruments of political action.

Notes:

1 Sarah Marusek, Wheelchair as Semiotic: Space Governance of the American Handicapped Parking Space, in: Law Text Culture 9 (2005), pp. 178-188.

2 Michael Oliver, The Politics of Disablement, Basingstoke 1990.

3 Spencer E. Cahill/Robin Eggleston, Managing Emotions in Public: The Case of Wheelchair Users, in: Social Psychology Quarterly 57 (1994), pp. 300-312.

4 Brian Woods/Nick Watson, The Social and Technological History of Wheelchairs, in: International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 11 (2004), pp. 407-410.

5 Gerard Delanty/Engin F. Isin, Reorienting Historical Sociology, in: Delanty/Isin (eds), Handbook of Historical Sociology, London 2003, pp. 1-8.

6 Herman L. Kamenetz, A Brief History of the Wheelchair, in: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 24 (1969), pp. 205-210.

7 Deborah Stone, The Disabled State, Philadelphia 1984.

8 Brian Woods/Nick Watson, In Pursuit of Standardization: The British Ministry of Healthʼs Model 8F Wheelchair, 1948–1962, in: Technology and Culture 45 (2004), pp. 540-568.

9 Michael Oliver, Understanding Disability. From Theory to Practice, Basingstoke 1996.

10 Henri Stiker, The History of Disability, tr. William Sayers, Ann Arbor 1999, p. 122.

11 Julie Anderson, ›Turned into Taxpayers‹: Paraplegia, Rehabilitation and Sport at Stoke Mandeville, 1944–56, in: Journal of Contemporary History 38 (2003), pp. 461-475.

12 John Silver, History of the Treatment of Spinal Injuries, London 2005, pp. 111-119.

13 Donald Munro, Rehabilitation Stifled by PVA, in: Paraplegia News, October 1949, pp. 1, 4, 6 (emphasis added).

14 Woods/Watson, History of Wheelchairs (fn 4).

15 Ministry of Labour and National Service, National Advisory Council on the Employment of the Disabled, Sheltered Employment Committee, Travelling Arrangements for the Disabled, November 1957: File MT98/150, Public Record Office, Ruskin Avenue, Kew, Richmond, TW9 4DU, UK.

16 Minute Sheet Correspondence from W. Hadfield, Highways Division, to R.S.S. Dickinson, 22 July 1958: File MT98/150, Public Record Office, Ruskin Avenue, Kew, Richmond, TW9 4DU, UK.

17 Minute Sheet Correspondence from J. Cane to D.A.R. Peel, 5 August 1971: File MT97/1168, Public Record Office, Ruskin Avenue, Kew, Richmond, TW9 4DU, UK.

18 Harry Schweikert Jr, D.C. Subway will be Accessible!, in: Paraplegia News, August 1973, p. 6.

19 Judd Jacobson, Letter to the Editor, in: Paraplegia News, November 1973, p. 2.

20 Jane Campbell/Michael Oliver, Disability Politics. Understanding Our Past, Changing Our Future, London 1996; Doris Fleischer/Zeida James, The Disability Rights Movement. From Charity to Confrontation, Philadelphia 2011.

21 Derek Seaton, From Strength to Strength. The History of the First 100 Years of the Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Guild of Disabled People, 1898–1998, Leicester 1998.

22 Ibid., p. 25.

23 Ibid., p. 38.

24 Henry J. Toombs, Architectural Suggestions: Ramps and Steps, in: The Polio Chronicle, August 1931, p. 4; Reinette Lovewell Donnelly, »Watch Your Steps«, in: The Polio Chronicle, February 1933, p. n/a; Architectural and Mechanical Hints Group, »Open Sesame«, in: The Polio Chronicle, December 1933, p. 10.

25 Toombs, Architectural Suggestions (fn 24).

26 Kitty Cone, Political Organizer for Disability Rights, 1970s – 1990s, and Strategist for Section 504 Demonstrations, 1977, an Oral History Interview conducted in 1996–1998 by David Landes, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000, URL: <https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/kt1w1001mt/>; Mary Lou Breslin, Cofounder and Director of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, Movement Strategist, an Oral History Interview conducted in 1996–1998 by Susan OʼHara, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000, URL: <https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/kt8r29n9sp/>.

27 Breslin, Oral History Interview (fn 26).

28 Woods/Watson, History of Wheelchairs (fn 4).

29 Oliver, Politics of Disablement (fn 2).

30 Anon., Letters Page, in: The Magic Carpet, March 1951, p. 22.

31 Anon., Ramps at Railway Stations, in: The Magic Carpet, June 1954, p. 56; Anon., The Policy Meeting, in: The Magic Carpet, Winter 1965, p. 3.

32 Nancy Bull, A Different Window, in: The Magic Carpet, Spring 1963, p. 12.

33 Robert Meier, Physical Facilities Report, in: Paraplegia News, March 1962, p. 7.

34 Anon., Steps are Stumbling Blocks to Misfortune, in: Paraplegia News, August 1955, p. 10; John Price, Editorial: Steps, Stairs and Stumbling Blocks, in: ibid., p. 2.

35 Sharon N. Barnartt/Richard K. Scotch, Disability Protests. Contentious Politics, 1970–1999, Washington DC 2001.

36 O.A. Denly, Access to and Circulation Within Buildings – General Considerations. Paper presented at a Symposium on Design Criteria for the Physically Handicapped, held by the Architectural Association at the Centre for Advanced Studies in Environment, 11–12 October 1967: File SA/MSS/A1 and A3 Box 1, Wellcome Trust Library, Archives of Modern Medicine, 183 Euston Rd, London, NW1 2BE, UK.

37 Selwyn Goldsmith, Designing for the Disabled, London 1963.

38 Ibid., p. 195.

39 Nancy Bull, Come the Revolution?!!!, in: The Magic Carpet, Summer 1963, pp. 58-62.

40 Denly, Access (fn 36).

41 Joe Hennessy, The Hennessy Report, in: The Magic Carpet, Summer 1982, pp. 4-6.

42 Barnartt/Scotch, Disability Protests (fn 35).

43 Eric Dibner, Advocate and Specialist in Architectural Accessibility, an Oral History Interview conducted in 1998 by Kathy Cowan, in: Builders and Sustainers of the Independent Living Movement in Berkeley, Volume III, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000, URL: <https://oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt4c6003rh;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=Eric%20Dibner&toc.depth=1&toc.id=0&brand=oac4>.

44 Breslin, Oral History Interview (fn 26).

45 Dibner, Oral History Interview (fn 43).

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Hale Zukas, National Disability Activist: Architectural and Transit Accessibility, Personal Assistance Services, an Oral History Interview conducted in 1997 and 1998 by Sharon Bonney, in: Builders and Sustainers of the Independent Living Movement in Berkeley, Volume III, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000, URL: <https://oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt4c6003rh;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=Hale%20Zukas&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e5351&brand=oac4>.

49 Anon., BART System to be Barrier-Free, in: Paraplegia News, May 1972, p. 7.

50 Ibid.

51 Zukas recalled at least one lawsuit against the BART on grounds of accessibility.

52 Cone, Oral History Interview (fn 26).

53 Jim Brown, Radical Fights Battles for Handicapped, in: Rocky Mountain News, 14 March 1982, p. 6; Gerry Delsohn, Disabled Snarl Traffic in Protest, in: Rocky Mountain News, 6 July 1978, p. 5; Mary Johnson/Barret Shaw (eds), To Ride the Public’s Buses. The Fight that Built a Movement, Louisville 2001.

54 Woods/Watson, History of Wheelchairs (fn 4); Brian Woods/Nick Watson, A Short History of Powered Wheelchairs, in: Assistive Technology 15 (2003), pp. 164-180.