Aus dem Amerikanischen von Martin Pfeiffer, Munich: Hanser 1988,

paperback edition: Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag 1990.

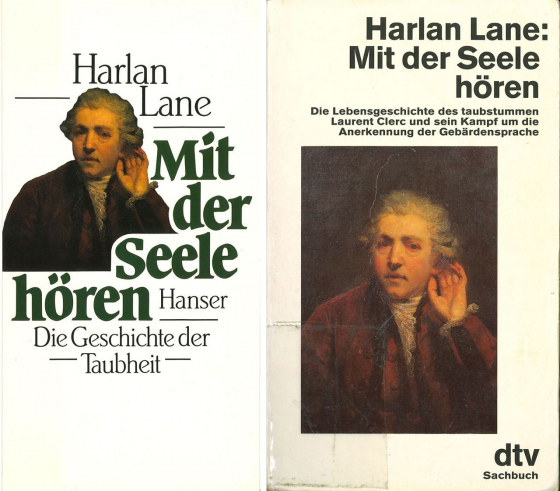

For the German book covers, the publishers used Joshua Reynolds’ painting

Self-Portrait as a Deaf Man (oil on canvas, c. 1775, Tate Gallery, London).

----------

Harlan Lane, The Mask of Benevolence. Disabling the Deaf Community, New York: Knopf 1992; German translation: Die Maske der Barmherzigkeit. Unterdrückung von Sprache und Kultur der Gehörlosengemeinschaft. Aus dem Amerikanischen übersetzt von Harry Günther und Katharina Kutzmann, Hamburg: Signum 1994.

----------

Harlan Lane/Richard C. Pillard/Ulf Hedberg (eds), The People of the Eye.

Deaf Ethnicity and Ancestry, Oxford: Oxford UP 2011.

I first came across Harlan Lane’s work towards the end of my PhD, which I was undertaking at University College London, UK. My dissertation was on the construction of ›difference‹ in the British Empire, particularly the differences ascribed to race and gender.1 Using nineteenth-century medical missionaries as a way in, I had started to think about differences evoked by health, disability, and the body. In particular, I noted the way in which missionaries used the language of disability as a discourse of racialisation. The African and Indian colonial subjects they encountered were described throughout missionary literature as ›deaf to the Word‹, ›blind to the light‹ and ›too lame‹ to walk alone.2 I have two d/Deaf cousins, one of whom is the sign language sociolinguist Nick Palfreyman, and around about this time Nick had started to familiarise me with some of the issues surrounding Deaf politics.3 Becoming interested and wanting to know more, I began to learn British Sign Language (BSL) and contemplate the connections between the historical work I was doing and contemporary struggles of Deaf politics and disability politics (I was particularly interested in DPAC – Disabled People Against Cuts – given the contemporary climate of austerity in the UK). As I did so I became acquainted with the work of Harlan Lane. Here, although acutely aware of my own positionality as a white, British, hearing woman, I have taken up the challenge set by the editors of this special issue to re-read his work twelve years on from my initial encounter with it, using the insights into postcolonial study I have gained through my historical work.

Born 1936 in New York and trained as a psychologist, Lane, who was hearing, first became interested in deafness, sign language and d/Deaf people in the 1970s. He was one of the people responsible for founding the American Sign Language (ASL) programme at Northeastern University in Boston, USA, and became a well-known and controversial advocate of d/Deaf people. Lane was a contributor to the argument that d/Deaf people in the US could or should be understood as an ethnic minority who shared important cultural, linguistic and historical linkages – rather, that is, than as a group defined through disability. He had a considerable influence on the shape of Deaf politics, intervening in debates about cochlear implants, Deaf heritage and the successful Deaf President Now campaign about the presidentship of Gallaudet University, a university for d/Deaf and hard of hearing people which, until this campaign in 1988, had nonetheless been led by a hearing person. On his death in 2019, Lane was remembered by Peter V. Paul in American Annals of the Deaf as a ›giant‹ of ›our scholarly world‹, and described by Roberta J. Cordano, Gaullaudet University’s current president, as having ›few peers‹ as ›a hearing person who advocated for the rights of Deaf people‹.4

Lane was a prolific writer whose body of work includes biographies, studies on the psychology of sign language, ASL, Deaf history and Deaf studies. Most relevant to my discussion here are When the Mind Hears. A History of the Deaf (first published in 1984) and The Mask of Benevolence. Disabling the Deaf Community (first published in 1992). My (1989) copy of When the Mind Hears is described in the blurb as ›the first comprehensive history of the deaf‹ and ›a powerful and compassionate study of the anatomy of prejudice and the motives and means of oppression‹. Whilst few would argue with the latter statement, the claim that it is a ›comprehensive history of the deaf‹ both marginalises anything beyond the French-US d/Deaf experience and overlooks some of the innovative features of the prose. For example, the book is striking in that it is substantially told from the first-person perspective of Laurent Clerc (1785–1869), the famous d/Deaf French teacher who co-founded American’s first school for d/Deaf people. Beginning with the words ›My name is Laurent Clerc. I am eighty-three years old […]‹, the book breaks new ground at the interface between history and biography, as well as marking a powerful intervention across disciplinary boundaries. Building on this, The Mask of Benevolence also makes a strong argument that d/Deaf people have been systematically disabled, not by their impairment, but by the hearing community. The book examines the medical and educational relationship between hearing and d/Deaf people from a variety of perspectives, including a colonial one (more on this below). Though Lane was not trained as a historian, his work on the history of d/Deaf people has been influential amongst both academic and lay historians of deafness and continues to be widely cited, including by scholars of deafness and Deaf history.5 There are a variety of ways in which Lane’s work can be read with postcolonial theory in mind, only some of which I explore here.

Part of the reason why I found Lane so interesting, coming from my background in critical colonial history, was the way in which colonialism features in his work on deafness in nineteenth-century France and the US. This comes across most strongly in The Mask of Benevolence, in which a chapter is devoted to ›The Colonisation of African and Deaf Communities‹. In it, Lane argued that there were important ›commonalities between the cultural oppression suffered by the colonised peoples of Africa and that suffered by deaf communities‹ (p. 32). In particular, as he puts it, (hearing) Africans and (white) d/Deaf people shared ›the physical subjugation of a disempowered people, the imposition of alien language and mores, and the regulation of education in behalf of the colonizer’s goals‹ (p. 31). Lane’s adoption of this position came through both his investigations into Deaf politics in the US and his journeys to Burundi in East-Central Africa. In the 1960s he had travelled to Western Africa to investigate English teaching in several English- and French-speaking countries. At this point he had yet to become familiar with d/Deaf people and ASL, but by the time he was invited to Burundi in 1976 in order to examine a young boy, John, he had had what he described as his ›fateful encounter‹ with ASL and d/Deaf people (p. 31). In this time he had also written The Wild Boy of Aveyron about a so-called ›feral boy‹, Victor, treated by the physician Jean Marc Gaspard Itard in France around the turn of the nineteenth century. On the basis of his research on Victor, the eminent American psychologist B.F. Skinner asked Lane to examine John, who was believed to have lived in the ›wild‹ for some years. John went on to form the subject of Lane and Richard Pillard’s 1978 book, The Wild Boy of Burundi, and Lane’s time in this country prompted him to make the colonial comparison that so intrigued me.

tell a Boston news conference of their plans to travel to Burundi

to study a boy reportedly found living with monkeys.

An enlargement of the newspaper article that called

their attention to the case is in the background.

Two years later, they published their book The Wild Boy of Burundi.

(picture-alliance/AP Images)

Laying aside the question of whether Lane as a white American can himself be seen as in some ways complicit in neo-colonialism or developmentalism in his work in Burundi, which was a former German colony and Belgian protectorate that has, since independence in 1962, seen continued violence, genocide and poverty, there are interesting points to be noted about the way in which the comparison between hearing Africans and d/Deaf Americans plays out in Lane’s writing. Whilst Lane’s consideration of this comparison can be seen to have come from his own direct encounters with both communities, there is a tradition of analogy between disability, race and colonialism, and his comparisons can be seen to be a part of this. In 1969 Leonard Kriegel famously compared the ›cripple‹ and the ›negro‹ in his reflections on life as a disabled white American,6 and, though Lane does not refer to and may not have been aware of this literature, other examples can be found both before and after the 1992 publication of The Mask of Benevolence. These include Thomas Szaz’s discussion of ›psychiatric slavery‹ (1977), Karen Hirsch’s analysis of the experience of people with disabilities undergoing a transition ›from colonisation to civil rights‹ (2000), and Gerard Goggin and Christopher Newell’s study of disabled people’s lives in Australia operating under a ›social apartheid‹ (2004).7 Such analogies have been written about by Mark Sherry as problematic conflations which, as he notes, also operate the other way around with postcolonial scholars describing (able-bodied) colonial subjects as being ›disabled‹ or even ›crippled‹ by colonial exploitation. I have also explored these analogies from a historical perspective.8 But what I wish to note here is that the violent histories of colonialism, far from simply being a trope that we can use to highlight a particular level of abjection – or as Lane puts it, ›the standard, as it were, against which other forms of cultural oppression can be scaled‹ (The Mask of Benevolence, p. 31) – have particular histories of disablement which are often overlooked when such analogies are being drawn.

Put most simply, one of the many legacies of colonialism has been that there are far more people living in the Global South, and particularly in formerly colonised territories (the two categories heavily overlap), with a physical impairment that in Western Europe and North America would be categorised as a ›disability‹, than there are in the Global North. Disease, poverty, warfare and ecological violence leading to malnutrition and related complications; meningitis and other disabling illnesses; maiming, injury and congenital anomalies; and long-term health conditions caused by pollution or chemical or nuclear exposure are just some of the contributory factors to this imbalance. And deafness is part of this trend, with high rates of deafness in sub-Saharan Africa due to illness, bacterial infection and unclean water supplies.9 As the critical race and disability theorists Jasbir K. Puar and Nirmala Erevelles have argued, the postcolonial creation of disability in the Global South complicates the celebratory narratives reclaiming disability as a positive identity which have been so powerful and important in the Global North.10 And scholars such as Helen Meekosha similarly urge us to rethink disability studies ›taking full account of the 400 million disabled people living in the Global South‹.11

The colonial analogies drawn by Lane and the others cited here are interesting also because they speak to a wider entanglement of the discourses of race and disability. The relationship between these categories is complex and fluid and something I have been attempting to explore in my recent work.12 From one perspective, disability, race and also gender operate as categories of difference where disabled people, people of colour and non-cis straight men are ›othered‹ from the non-disabled, white, heterosexual male who, in colonial and imperial metropolitan discourse, increasingly became hegemonic, operating as he did to signify ›normalcy‹. When these categories intersect we therefore get some surprising omissions – Lane does not, for example, discuss African or African-American people who are d/Deaf. Rather, d/Deafness in his writing is implicitly constructed as white, and people of colour in the US and in Africa are implicitly depicted as able-bodied. This is a perspective that is possible only because of the power of whiteness and able-bodiedness to operate as unmarked signifiers. Further, as Douglas Baynton has powerfully argued in the American context, disability has historically been a language through which to articulate other forms of gendered and raced inequality – women could be excluded from the franchise on the grounds of their alleged intellectual and physical fragility, and people of colour could be excluded on the grounds of their association with people with learning disability. That physical, emotional and intellectual impairment would incapacitate a person from voting responsibly became, in these discourses, common sense.13 Indeed, race and disability mutually influenced each other, with imperial commentators writing of non-disabled people of colour using the language of physical anomaly. Deaf people, to take the example most pertinent to this piece, were described, as Baynton has explored, as ›foreigners in their own land‹.14 From another perspective, race and disability have different histories and are constituted in relation to particular groups of people with their own histories, the specificities of which it is important not to lose through careless conflation. Such relationships are complicated, but what we can more easily deduce is that when Lane spoke of deafness he also spoke of whiteness. He also, we might note, meant maleness, as it must be stressed that Lane’s focus is almost exclusively on men.15

Also apparent in Lane’s work is an amnesia around the colonial histories of various metropoles he explores. That is, Lane fails to acknowledge that France, the UK and the US were, each in different senses, imperial metropoles in the periods about which he writes (the nineteenth and twentieth centuries). Drawing on the work of postcolonial scholars such as Frantz Fanon, who famously argued that ›Europe is literally the creation of the third world‹, and of critical colonial historians such as Catherine Hall, Antoinette Burton and Kathleen Wilson, who have helped to unpick the conceptual divide between metropoles and colonies and to address the historical amnesia many in Britain (and the other colonial metropoles that appear in Lane’s work, the US and France) have about their country’s imperial past, we might critique this from a postcolonial perspective.16

It might finally be argued that Lane, whilst highly respectful of Deaf culture and d/Deaf people, was nonetheless inclined at times to use some of the colonial tropes towards d/Deaf people that I have explored in my work on hearing-deaf encounters in imperial Britain being akin to those between colonisers and colonised.17 When interviewed in 2011, Lane recalled his excitement at encountering d/Deaf students signing to one another for the first time in the 1970s and his learning ›that what they were using was a certifiable language‹. He said ›I became quite excited because I realized there was a whole new way to look at the psychology of language. I felt like Balboa discovering the Pacific.‹18 Lane’s figurative identification here with the sixteenth-century Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa is interesting because it echoes the language of many nineteenth-century British hearing people who, when encountering d/Deaf communities, wrote of ›discovering‹ a ›strange people‹. ›Deaf-and-Dumb Land is a new country to me‹, wrote the social investigator Joseph Hatton when visiting the Margate Deaf and Dumb Asylum in 1896. ›For a time it affected me as might have done the discovery of a new country. [...] I experienced some of the sensations of a discoverer.‹19 In the context of late nineteenth-century Britain, the imperial tropes redolent in such thinking are plain to see and have clear linkages with Lane’s own example. We might perhaps say that Lane identified a (post)colonial problem in his studies, but that he nonetheless in some ways remained part of this framework.

To conclude a reading of any seminal text in disability studies at this time, it is necessary to make a plea for more work to be done. As Jasbir K. Puar has argued, the ›whiteness‹ of disability studies (and the same might be said for disability history) is something of an ›open secret‹, flagged by Christopher M. Bell for some time.20 Important work has already been done by theorists such as Bell and others.21 Nonetheless, more research must follow to understand, unpick and interrogate disability studies and disability history from a postcolonial perspective.

Notes:

1 Esme Cleall, Thinking with Missionaries. Discourses of Difference in India and Southern Africa, c. 1840–1895, doctoral thesis, University College London 2009.

2 Cf. Esme Cleall, Missionary Discourses of Difference. Negotiating Otherness in the British Empire, 1840–1900, Basingstoke 2012.

3 The convention is to use ›deaf‹ with a small ›d‹ as an adjective to discuss an auditory state, whereas to capitalise it as ›Deaf‹ if an identity or affiliation with Deaf politics is mentioned. Thus someone might be both deaf and Deaf. In Deaf history writing, one way of approaching this is to use ›d/Deaf‹.

4 Peter V. Paul, Remembering and Debating Harlan Lane, in: American Annals of the Deaf 164 (2020), pp. 525-530; Cordano quoted in Richard Sandomir, Harlan Lane, 82, Is Dead, in: New York Times, 29 July 2019.

5 See for example multiple citations and an extended acknowledgment for ›transforming our worlds in the most positive ways‹ in: Paddy Ladd, Understanding Deaf Culture. In Search of Deafhood, Blue Ridge Summit 2003. For uses of Lane’s work, see also: Jan Branson/Don Miller, Damned for their Difference. The Cultural Construction of Deaf People as Disabled. A Sociological History, Washington, D.C. 2002; Jennifer Esmail, Reading Victorian Deafness. Signs and Sounds in Victorian Literature and Culture, Athens 2013; Douglas C. Baynton, Forbidden Signs. American Culture and the Campaign against Sign Language, Chicago 1996; Jonathan Rée, I See a Voice. A Philosophical History of Language, Deafness and the Senses, London 1999.

6 Leonard Kriegel, Uncle Tom and Tiny Tim: Some Reflections on the Cripple as Negro, in: The American Scholar 38 (1969), pp. 412-430.

7 Thomas Szasz, Psychiatric Slavery, New York 1977; Karen Hirsch, From Colonization to Civil Rights: People with Disabilities and Gainful Employment, in: Peter David Blanck (ed.), Employment, Disability, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Issues in Law, Public Policy, and Research, Evanston 2000, pp. 412-431; Gerard Goggin/Christopher Newell, Disability in Australia. Exposing a Social Apartheid, Sydney 2004.

8 Mark Sherry, (Post)colonising Disability, in: Wagadu 4 (2007), pp. 10-22; Esme Cleall, Orientalising Deafness: Race and Disability in Imperial Britain, in: Social Identities 21 (2015), pp. 22-36.

9 Bradley McPherson/Susan M. Swart, Childhood Hearing Loss in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review and Recommendations, in: International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 40 (1997), pp. 1-18; Sanjay Kumar, WHO Tackles Hearing Disabilities in Developing World, in: Lancet 358, 9277 (2001), p. 219. Cited in <https://www.hear-it.org/causes-of-hearing-loss-in-africa>.

10 Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim. Debility, Capacity, Disability, Durham 2017; Nirmala Erevelles, Disability and Difference in Global Contexts. Enabling a Transformative Body Politic, New York 2011.

11 Helen Meekosha quoted in Puar, The Right to Maim (fn 10), p. 67.

12 These points are further discussed in: Esme Cleall, Colonising Disability. Impairment and Otherness Across Britain and Its Empire, c. 1800–1914, Cambridge 2022.

13 Douglas C. Baynton, Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History, in: Paul K. Longmore/Lauri Umansky (eds), The New Disability History. American Perspectives, New York 2001, pp. 33-57.

14 Baynton, Forbidden Signs (fn 5), pp. 15-35.

15 Editorsʼ note: On intersectionality, see also the essay by Sebastian Schlund in this issue.

16 See, for example, Catherine Hall/Sonya O. Rose (eds), At Home with the Empire. Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World, Cambridge 2006.

17 Cleall, Colonising Disability (fn 12).

18 Harlan Lane quoted in Kara Shemin, Deaf Cultural Ties Linked to Ethnic Group Bonds, in: News @ Northeastern, 1 March 2011.

19 Joseph Hatton, Deaf-and-Dumb Land, London 1896, p. 9.

20 Puar, The Right to Maim (fn 10); Christopher M. Bell, Introduction: Doing Representational Detective Work, in: Bell (ed.), Blackness and Disability. Critical Examinations and Cultural Interventions, Berlin 2011, pp. 1-8.

21 Besides Bell, see also Erevelles, Disability and Difference (fn 10); Theri Alyce Pickens, Mad Blackness, Durham 2019; Stefanie Hunt-Kennedy, Between Fitness and Death. Disability and Slavery in the Caribbean, Urbana 2020.