Group of visitors at the inter-German border, Mödlareuth (Bavaria), 1985/86

(Photo: Archive Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur [Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship], collection Uwe Gerig, picture 4809)

The Iron Curtain dividing West and East Germany during the Cold War was always more than a geographical boundary. Originally imposed as a demarcation line between the Western and Soviet occupation zones, it became increasingly impermeable as the former Allies drifted apart and was eventually fortified to such a degree that attempts to cross it turned into life-threatening endeavors. As a military installation, the border could be deadly. As a political metaphor, it had major rhetorical purchase throughout the Cold War.1 On a less metaphorical level, however, the German Iron Curtain turned into a tourist attraction. While border tourism peaked in the years after the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the consumption of the inter-German border as a tourist commodity had started well before, lasted through its dismantling in 1989 and continues as commemorative tourism to the present day.2

The history of the 1,393 kilometer stretch of border, from Lübeck in the north to Hof in the south, has long been overlooked in favor of the more iconographic Berlin Wall. Like no other event or structure, the Berlin Wall bundled Cold War anxieties, making it a powerful international symbol. Slicing through a vibrant metropolis and spatially reorienting its inhabitants, the Wall produced the kind of human drama that captured the attention of publics worldwide. The very term ‘Iron Curtain’ became almost synonymous with the Berlin Wall despite the fact that the inter-German border was both equally dangerous and much longer, and that a similarly fortified boundary existed (and continues to exist) at another Cold War hotspot, between North and South Korea. This article purposefully circumvents the Berlin Wall and introduces the little known phenomenon of tourism to the Iron Curtain, using the example of the inter-German border.

Border tourism was a sizable phenomenon although the number of visitors cannot be determined with precision. There were, after all, no tickets sold for visits to the Iron Curtain. Border tourists were nonetheless accounted for, albeit in varying estimates. The West German border guards counted them since it was part of their job to ensure that these sightseers stayed out of trouble.3 Public officials counted them because they had to justify the expenses for the upkeep of a tourist infrastructure along the border.4 East German border guards counted them because the steady stream of visitors was considered a major provocation.5 The figures that can be found in the various sources produced by these respective agencies suggest that border tourism was a large phenomenon: In 1969, for instance, 1.65 million people came to see the border, 23,000 of whom were foreigners.6 The demand does not seem to have abated in later years. For 1978, the information centers along the border reported an average 153,282 visitors per month, amounting to an annual surge of 1.84 million.7 In 1985, the GDR Border Command North counted 212,555 civilians in the northern sector alone.8 Because they were dispersed over the entire stretch of the inter-German border and over the course of the year, however, border visitors were not necessarily perceived as descending upon the border en masse. East and West German border guards regularly commented on the seasonal fluctuations in the stream of visitors. The trips peaked during the summer months, particularly on 17 June when West Germans commemorated the GDR workers’ uprising of 1953.

2![]()

The bulk of this border tourism took the form of day trips (Tagesausflüge), undertaken individually and in organized tours. Government officials on the federal, state, and local level encouraged such trips and provided funding for travel parties if the trip was framed as an educational excursion.9 As discussed in further detail below, the goal of such trips was to demonstrate an unwavering commitment to the Germans on the other side of the fence, to express a desire for German unification on West German terms or, in later years, at least to uphold a sense of the ‘unity of the German nation’.10 The state funding was also intended to bring visitors into the suddenly peripheral new borderlands lest its residents feel ‘forgotten’ by their government. Yet the underlying motivations to encourage or undertake border travel became more formulaic as the years went on, pointing to the oft-noted process through which West Germans became accustomed to partition, and to their country’s predominantly western orientation in politics, culture and consumption.

This article seeks to show how border tourism contributed to the increasing acceptance of living in a divided country. Such a contribution arose out of a paradoxical tension, or ambiguity, inherent in this activity. Insisting on the abnormality, and even brutality, of the division created by the border made this military installation an attraction and drew streams of curiosity seekers to the Federal Republic’s territorial edge. But those very visitors and the infrastructure developed to service them unwittingly contributed to the growing acknowledgement that the border was an element of an enduring postwar reality in Germany. In other words, seeing the border and visualizing the partition of the country did little for overcoming it but rather tended to underwrite the political and territorial status quo.

1. The Infrastructure of Border Tourism

The border was an attraction without an established genealogy; it was new to the landscape. Although it coincided at times with historical state frontiers and boundaries of former administrative units, the postwar Iron Curtain meandered through the country in striking arbitrariness. Only a few regions that the border crossed and divided, such as the Harz mountains, had some previously established tourist facilities and experience with travelers. For the most part, a tourist infrastructure catering to the interests and needs of border visitors appeared only in response to the phenomenon itself, and soon reinforced it. Elements of this infrastructure, to be encountered throughout this essay, included postcards, souvenirs, travel guides, observation towers, information points, and parking lots as well as inns and restaurants.

3![]()

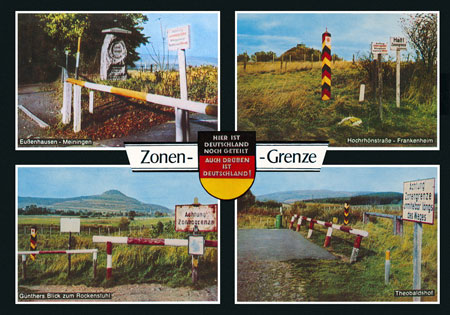

The earliest signs of a budding interest in the Iron Curtain were picture postcards. A card from 1951 already features the inn Interzonen-Klause at the border crossing in Helmstedt. The card showed the exterior of the Klause, the lounge, the inn-keepers at the bar as well as trucks queuing at the checkpoint. Such inns at checkpoints catered to border crossers who still passed the demarcation line, or ‘green border’, with a permit.11 In 1952, these supervised border crossings were severely restricted when the GDR made major efforts to seal off the demarcation line and resorted to the deportation of allegedly unreliable residents in the five-kilometer deep eastern security zone.12 While the traveler who mailed the card in 1951 was not a leisure tourist visiting the border as a sight, the card itself follows the conventions of picture postcards produced for holiday destinations by offering ‘greetings from the zonal border’.13

Helmstedt was not just any checkpoint. Driving from Helmstedt’s Checkpoint Alpha to Checkpoint Bravo at Dreilinden was the shortest transit route to West Berlin and vital for the supply of the city, including the military bases of the Western Allies. This particular route quickly rose to prominence as Soviet authorities regularly tinkered with the transit rights of the American and British militaries, only to shut it down completely during the Berlin Blockade. But even after the Blockade, petty obstructionism continued, keeping Helmstedt in the news and turning the checkpoint into the symbol of an unpredictable and anxiety-ridden journey.14 The image of Checkpoint Alpha, with the flags of the Western Allies flying, was therefore easy to decode during the 1950s as part of the Iron Curtain. It was one of the few illustrations that convincingly conveyed a sense of ‘border’ and simultaneously reflected the political significance of this sensitive liminal space. Postcards featuring Checkpoint Alpha therefore became quite common during the 1950s.

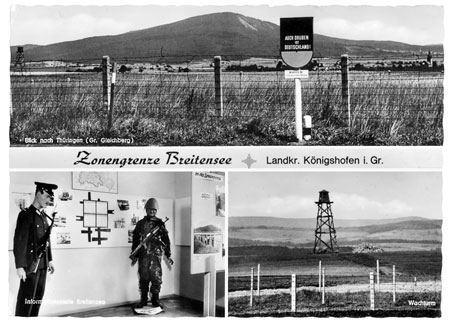

Unlike Helmstedt cards, however, other postcards displayed a tension between what they sought to represent and what was visually available to do so because most of the border was not yet heavily fortified. Events during the early 1950s such as the Korean War, the insecurities related to the succession of power after Stalin’s death, the East German workers’ uprising of 1953, and incidents directly at the border coalesced into one of the Cold War anxiety clusters that made the Iron Curtain loom menacingly in the imagination of the ‘free world’. The early postcards, however, could not visually capture this anxiety and its political significance because the Iron Curtain’s fortifications were not yet commensurate with its growing Cold War importance.

4![]()

A card from the town Hohe Geiß in the Harz mountains is a case in point: While a few random poles imply a boundary, the generous spacing of the poles suggests permeability instead of closure. A visiting family looks into a field of grass and only a western sign, erected by the Consortium for an Undivided Germany (Kuratorium Unteilbares Deutschland), announces that ‘Here Germany is Still Divided. On the other side, too, is Germany’. If it were not for this western intervention, the card would be visually mute, reduced to a depiction of a family contemplating a meadow. Another example from the Bavarian Forest from the late 1950s relies solely on the viewer’s imagination, as an unobtrusive wooden railing represents the demarcation line. In another context, the same railing could have fenced in a cattle paddock. If it was not for the border warning sign (‘Halt! Grenze’) and the Bavarian border policeman in the picture, the card might depict a nondescript mountain scene in which the wooden tower held no particular meaning.15 Tellingly, picnic benches and tables were provided on the Western side, defining the site as scenic or otherwise worth stopping for, but hardly conveying the menace of the Iron Curtain.

Only during the overhaul of the border fortifications during the 1960s and 1970s did the inter-German border acquire the features that are remembered today as representing its danger and ugliness: the double metal fences, concrete slabs, mine fields, dog runs, walls, spring guns, and observation towers.16 Postcards from the 1970s and 1980s could draw on a broader range of motifs and offer more telling illustrations. The very fact, however, that the border appeared already on postcards throughout the 1950s when, arguably, the Iron Curtain did not yet look like much, allows us to see the process during which the border was transformed from a site into a sight (as in sightseeing). The changing visuals on these cards and, indeed, their very existence, helped to reproduce the border culturally and allowed recipients to ‘picture’ the sight. Such an argument is limited, however, to the visual message of these cards since we do not know much about how they were used or in what quantities they were produced and sold. There is evidence that refugees from East Germany actually chose cards with border motifs in order to mail them to relatives in the GDR, even to people living in border communities, as a deliberate provocation of East German authorities.17 Many cards, however, might never have been mailed but served as souvenirs instead.

Border tourists could, in fact, acquire other Iron Curtain souvenirs. The Helmstedt border museum displays an ashtray and a demi-tasse from the 1950s featuring the checkpoint in that town so frequently depicted on postcards. These objects can be read either as typical tourist kitsch or as valuable mementos of a trip once taken. In tourism research, the purchase of souvenirs and the mailing of postcards are considered the signature of ‘successful’ tourism. The successful tourist has seen the main sights, has climbed the famous mountain, has visited the indispensable exhibition, and produces proof of his or her trip. Such objects testify to the commodification of sights worth seeing; the sight is reproduced in merchandise and can be consumed as a tourist commodity.18 While this insight from cultural studies might be easily acceptable for the Eiffel Tower as a keychain, the shot glass with a Rhine motif, or the inevitable Black Forest doll, it sits less well for an ashtray with an Iron Curtain motif or a keepsake from the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone) between North and South Korea.19

5![]()

This unease points to a tension inherent in a form of travel that tourism researchers have begun to call dark tourism: the ‘consumption of real or commodified death and disaster sites’.20 The leading scholars of this phenomenon tie it closely to postmodernity and argue that dark tourism is fueled by global communication technologies that create or enhance the visibility and notoriety of an object or site, such as locales related to John F. Kennedy’s assassination, or Pont de L’Alma in Paris where Princess Diana died. While some venues of dark tourism emphasize historical education, these educative elements nonetheless commingle with the commodification of the site; the stream of visitors offers the opportunity to develop a ‘tourism product’ and gain a mercantile advantage.21 Dark tourism might at times border on mere sensationalism, but both phenomena share a morbid fascination with death, suffering, and past and present danger. Some contemporaries involved in border tourism had a similar sense of the endeavor. After 1990, a hotel manager from the border triangle of Hesse, Bavaria, and Thuringia called the phenomenon Gruseltourismus: ‘spooky tourism’ that gives one the creeps. ‘We always had tourism,’ he said, ‘but a very special kind, the so-called “Gruseltourismus”! Busloads of people came from Holland, from the Ruhr area and peeked over the German-German border.’22

Group of visitors in Zicherie, 1979

(Photo: Jürgen Ritter, http://www.grenzbilder.de, No. c8306, reproduced with permission)

Some locations along the border were better equipped to trigger such sensations than others. Put differently, border tourism, too, had a distinct hierarchy of what constituted a sight worth seeing. The sensation of the Cold War frontline was most gripping where the border seemed the most ruthless and absurd. Thus, highly frequented locations included Böckwitz-Zicherie near Gifhorn in Lower Saxony where a wall separated two villages with close historical ties.23 A similar wall, erected in 1966, divided the minute village of Mödlareuth and its 50 inhabitants.24 The border could be even more incisive, running right through a house. The print shop of the Hossfeld family in Philippsthal on the Werra was affected this way. In 1951, the family hauled the machines into the western part of the building to prevent confiscation and was consequently no longer allowed to enter the eastern part of the house. The idea of a divided house with the sharp contrast between the neatly renovated western half and the dilapidated state of the eastern half – an image that corresponded well with West German propaganda about material scarcity under socialism – was too good to pass up: ‘This side of the building’, a news article reported, ‘appears well-kept; here people live and work. The other side breathes decay and destruction.’ The Hossfeld print shop thus was regularly featured on border tours.25

A second set of tourist attractions that falls into the definition of dark tourism were sites of escapes and spectacular escape attempts across the border. In August 1969, for instance, a family of nine, including a GDR admiral, escaped near Helmstedt. The Bild Zeitung ran an 8-part series on the Oborny family, which drew crowds to the escape spot over the ensuing weeks, to which enterprising Helmstedters responded with sausage stands and beer carts.26 Similarly, the resort town Hohe Geiß in the Harz mountains was the site of an escape attempt in 1963. The refugee was shot and died just a few yards away from the demarcation line, in plain view of a throng of western spa visitors. The parking lot adjacent to this death site quickly became a major attraction for years, featuring a memorial cross with the victim’s name.27

6![]()

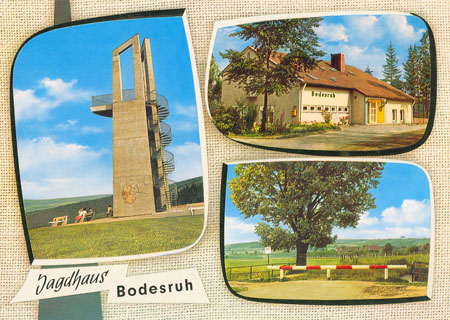

Finally, a third way to enhance the ‘dark’ character of the border was to emphasize the increasingly dangerous border fortifications through an elevated view. Seeking vistas and consuming landscape from natural elevations like mountains or artificial viewing points such as look-outs has been a staple of the traveler’s experience since at least the late eighteenth century.28 The look-out towers along the inter-German border followed established conventions in that they were erected at locations that promised a sublime view of the landscape. However, what distinguished these towers from constructions solely displaying romantic vistas was that some of them were also conceived as monuments (Mahnmale) in favor of reunification. They put the border fortifications and the East German borderlands on display as the center of the panoramic view.29 Without this added function, towers like Thüringerwarte in Lauenstein (1963), Bayernturm in Zimmerau (1966) or the ‘Monument German Division’ in Bodesruh near Kleinensee (1961-64) would most likely not have been erected.

If viewing from any look-out tower already offered a sense of visual control of the scenery, this sentiment was enhanced by those border towers built for the explicit purpose of exhibiting the GDR border fortifications. The growing number of tourists along the border was considered a major provocation by East German authorities, triggering various measures to undercut the attraction of border viewing – the less the western visitor would see, the better.30 However, the aerial view from a tower on the western side foiled any such efforts. It demystified the fortifications by allowing the visitor to fully take in its intricacies, see beyond the impenetrable wire mesh of the metal fences and discern the deeply layered structure of the Iron Curtain. What was forbidden knowledge for East Germans was openly displayed on the western side, and it particularly galled East German authorities that former GDR citizens were among the frequent visitors of such towers.31 Just how enmeshed the functions of the towers were with the mission to expose the border fortifications became clear after 1990: Some towers and platforms were simply demolished.32

Info panel at Hirschberg near Hof, Bavaria

(Photo: Jürgen Ritter, http://www.grenzbilder.de, No. u0920)

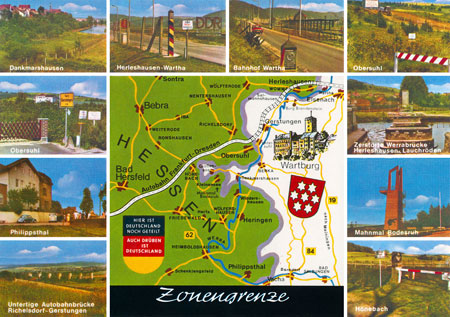

Observation towers and monuments, however, were a considerable investment for a community even if state subsidies were in the mix. It was cheaper and less sumptuous to set up wooden viewing platforms at points of natural elevation or outdoor information panels and kiosks. Some communities also established information centers, usually in the town hall, municipal center, church or school rooms, or at headquarters of the resident border guard regiment. Maintained by dedicated individuals who, in several cases, were also activists for the local branch of the Consortium for an Undivided Germany, these centers offered information materials and lectures with slides. Their exhibitions featured maps, models of the border fortifications, uniforms, and, if available, weapons of GDR border guards. In their earliest incarnation during the first half of the 1960s, the exhibitions made the most of juxtaposing Western freedom with Eastern captivity. However, they were not exclusively centered on the GDR. The exhibitions also made a point of moving beyond ‘the mere barbed-wire situation’ and emphasized the consequences of the Iron Curtain for borderland residents on the western side.33 By 1978, Bavaria had 15 such information centers, Hesse 14, and Schleswig-Holstein 10, while Lower Saxony supported 27 with an additional 24 outdoor points of interest that were equipped with information panels or kiosks.34 Lower Saxony, the state that shared the longest stretch of border with the GDR (544 km), had taken the lead in establishing such centers in the first half of the 1960s. The centers were a response to the growing number of visitors who were taxing the time and patience of local officials.35

7![]()

The fate of these information centers varied. At times, the departure of a dedicated individual ushered in a center’s decline. The founder of the one at Offleben near Helmstedt withdrew in 1971. Soon thereafter, the county no longer wanted to bear the heating and cleaning cost, the janitor was fired, and the exhibits were frequently vandalized. It was finally closed in 1976.36 On the other hand, during the tenure of Minister President Ernst Albrecht (CDU), Lower Saxony invested significantly in restoring and refurbishing its border infrastructure throughout the 1980s. The county of Helmstedt, for instance, initiated efforts in 1983 to turn a local landmark into a monument (Mahnmal). The object in question was the hulk of a burned omnibus that the Allies had dragged on the demarcation line in 1945 to block the road. With subsidies from Hanover that were needed to cover the ever escalating costs, the rusty wreck was made to serve as a ‘political symbol’, representing freedom (because it stood on the western side) and telling tales of border crossers and smugglers.37 Bad Bodenteich near Uelzen received a new border information center as late as 1988; the customs service in Hesse opened a new one in Tann in 1987.38 These cases are just a few of many indicators that the border had become a fixture in the landscape, the mental as well as the actual one. Local communities remained engaged with border tourism until autumn 1989; the pertinent infrastructure was then either removed, dismantled, and demolished – a fate that caught up with the Helmstedt bus wreck –, or re-dedicated to serve as memorials to German partition, catering to the Cold War commemorative tourism that flourishes today.39

2. Border Travel as Political Propaganda

Federal and state officials in charge of border-related matters appear to have assumed a rather linear effect of border travel and hence lent it significant financial support. ‘The closer one lives to the Iron Curtain,’ a reporter for Neue Zeitung noted in 1951, ‘the more its danger serves as [political] stimulation.’40 Seeing the border or living near it, the reasoning went, would shake up West Germans and turn them into politically engaged citizens. Politicians considered a visit to the border especially beneficial for high school students. A confrontation with the border fortificiations would inoculate them against ‘communist infiltration’.41 School classes, sport clubs, choirs, church groups, and a whole range of associations (Vereine) availed themselves of subsidies provided by the Ministry of All-German Affairs in order to experience the ‘zonal border’, as it was still called well into the 1970s. Once on site, these visitors could count on the expertise of the West German border guards who doubled as ‘tour guides’. Groups could book border tours with the local office of the customs or border guard unit. This practice was encouraged by West German authorities in order to prevent visitors from violating the demarcation line, which could trigger an encounter with Eastern border guards, and to ensure that they would receive information about the border fortifications that would turn the trip into political education.

How these visits to the Iron Curtain were meant to politicize the visitor emerges from an analysis of the travel guides that state agencies made available to such groups before their trip or at border information points. The political message of the travel guides was rather straightforward: Whoever saw the border, a Bavarian example stated, would instantly grasp the ‘horrible consequences of the Second World War for our people’. Being confronted with ‘a communist system’ (the mention of the GDR was carefully avoided) ‘allows us to appreciate the value of our freedom of movement’.42 The juxtaposition of freedom in the West and captivity in the East was a running theme in these brochures. They also left no doubt about the blame for the current conditions. The GDR appears as the ‘outpost of Soviet desires for expansion’ where ‘the Communist regime in the unfree part of our fatherland does its utmost to make the separation of Germans from Germans even harder, ever more unrelenting and inhumane’.43

8![]()

One way or another, a border visit was expected to become a transformative experience. A 1964 guide from Hesse assumed the trip would shake visitors out of ‘the wide-spread lethargy’, which was probably an unintended acknowledgement that many West Germans had become quite used to partition already. Once the traveler saw the border fortifications, felt the binoculars of GDR border troops follow each of his or her movements, and realized that ‘German people [on the other side] put their life on the line by simply waving at us […] the visit would cease to be a leisurely getaway’.44 A guide from Lower Saxony published two years later assumed that by seeing minefields and barbed wire, the visitor would find the courage to fight ‘injustice and violence’ in favor of ‘justice and freedom’. To do so was the ‘great national task’ that the brochure, and by extension the border trip, sought to serve.45 Although the guides advocated nourishing contacts to Germans in the GDR, those published in the 1960s were fully fixed on the military fortifications, border viewing points and places to stay in the borderlands. Only guides published in the 1980s contained information about towns on the other side of the fence and the political system of the GDR. The tone in these later publications was also less confrontational.46

Government officials had not only domestic but also foreign audiences in mind when they advertised border travel. These travel guides and other materials on the border were therefore also printed in English, French, and Spanish.47 In fact, the border could serve as a valuable foreign policy asset. It allowed the West German government to boost its anti-communist credentials and present itself as a worthy and reliable partner in the Western Alliance. During the Adenauer era, this was an attractive prospect for a country that was constantly reminded in the international arena of the crimes committed in its name in the not so distant past. Highlighting the injustice of the border could thus allow West Germans to distance themselves from responsibility for popular support of the Nazi dictatorship by providing the opportunity to warn the Western world about the ‘new totalitarianism’ across the Iron Curtain.

This idea lay at the core of the emerging border program for foreign visitors coordinated by the Foreign Office in Bonn. By the late 1950s, a routine for such border visits was well established.48 A West German diplomat would accompany each group – ranging from British ladies’ clubs, to foreign correspondents, diplomats, and heads of state – and report back to the Foreign Office. The visitors’ reactions were usually highly satisfactory. They confirmed that they had never seen such an ‘inhuman demarcation line’;49 a French member of parliament declared in Helmstedt that he had now seen ‘a new Germany’;50 Latin American bishops experienced the ‘confrontation with militant atheism’;51 and representatives of the British European Union of Women, having heard a GDR border guard firing his gun, vowed to report about the border’s dangers back home.52

9![]()

The effect was intensified when the choreography of such a trip combined a former concentration camp with a visit to the border. A group of former Belgian resistance fighters did just that. In November 1959, they requested the opportunity to visit Bergen-Belsen, lay down a wreath, and continue on to see the border. The request dovetailed nicely with efforts of the Bonn government to invoke the imagery of concentration camps in government brochures about the border. By implying that the GDR was a large concentration camp, indeed, ‘the largest of all times’ as a 1961 brochure put it, the continuity of totalitarianism could be safely located in East Germany.53 To link Belsen with Helmstedt was a winning strategy in that regard. By traveling from Belsen to Helmstedt, the visitors left the recent German past behind and arrived in the West German present. The report to the Foreign Office stated: ‘The visit to the memorial at the former concentration camp Bergen-Belsen on a foggy and dim November day provided a transition for the visit to the border with its barbed wire and watch towers that could not have been more impressive. Time and again the participants declared that they believed themselves at the fence of a gigantic concentration camp.’54 The crowning endorsement of the Belgian résistants came at the Berlin Wall where mayor Willy Brandt called West Berlin ‘a city of resistance’. Deeply impressed by how Berliners braved the onslaught of totalitarianism, the spokesman of the group, Hubert Halin,55 declared that Berlin ‘displays the same spirit of resistance against totalitarianism that had animated [ourselves]’ against the Nazis.56 If former resistance fighters against German military occupation granted the holy status of résistance to their former occupiers, the West German Foreign Office might safely count the trip as a success.

3. The Visitors and the Visited

What did other visitors get out of a border trip? We know more about the intentions of state agents who provided funds and publications to stimulate border travel than about the experience of those who made the journey. Local newspapers frequently reported on border visits. Once such visits became institutionalized, however, they lost their news value; as such, only dangerous incidents or the visits of political dignitaries received press coverage. There are a few core constituencies of border travel, however, about which one may make some preliminary observations.

Among these were expellees from former German territories as well as refugees from the GDR. For both groups, the demarcation line was the closest point they could approach their former homelands, at least until the fruits of Ostpolitik, including the rapprochement with Poland in 1970 and the Basic Treaty with the GDR in 1972, eased travel restrictions for trips to Poland and into the GDR.57 Thus barred from commemorating their homelands at ‘authentic places’, the border became the next best location.58 Expellees and GDR refugees participated in border-related activities through the Consortium for an Undivided Germany and through their various Landsmannschaften, organizations defined by the home regions of their members. Among other things, such Landsmannschaften sponsored the erection of several large crosses in immediate proximity to the border, widely visible monuments in the landscape that served as sites of mourning and were intended to keep alive a desire for reunification. These crosses, in turn, became incorporated into the annual activities of expellee organisations, drawing crowds for outdoor church services, reunions, and 17 June commemorations as well as group tours and hikes.59 The border thus turned into a performance zone or, as a journalist noted critically, into a ‘relic for mythical stagings. A multi-purpose backdrop for May Day rallies, for jumps over bonfires and deep sighs during border hikes.’60 It appears that expellee organizations were among the first to tour the border in large groups, a development that was quickly noticed and interpreted as major ‘revanchist’ provocation by East German authorities.61

10![]()

Other identifiable constituents of border travel were high school students, Bundeswehr recruits and Allied soldiers stationed in West Germany who could be classified as ‘captive audiences’. For military personnel, a trip to the border for the study of the layered fortifications was part of their military training. East German border guards meticulously counted anybody in uniform and tried to identify insignia.62 For high school students, trips to the border or an excursion to West Berlin were often part of the curriculum as civic education on site. At a secondary school in Frankfurt, a dedicated teacher, Dr. Willi K., regularly organized three-day trips to the borderlands in order to acquaint the students with the German question in its current guise. After the trip, sponsored by the Hessian Bureau for Political Education, the students produced reports, adorned with their own photographs and drawings.63

The 1961, 1962 and 1968 scrapbooks show that the students experienced, or at least depicted, the border as a threat; the accompanying West German border guards thus appear less as tour guides and more as bodyguards. The students emphasized the absurdity of the border that made nearby villages and buildings unreachable and ‘separates Germans from Germans’, thereby echoing closely the government brochure ‘In the Heart of Germany’. In their observations the border fortifications held center stage: the meticulously raked ten meter strip intended to record footsteps, observation towers, barbed wire, mines, watch dogs, and cut-off roads or tracks impressed upon them ‘how absurd the forceful division of Germany’ was and caused feelings of trepidation. Such sentiments were reinforced by lectures that emphasized the brutality of the East German border guards, their lack of ‘fair play’ when they pursued refugees over the demarcation line into western territory and snatched them back, and the impact of the border on everyday life in the borderlands. Judging by the scrapbooks, Dr. K’s class trips were exemplary border visits that reinforced the Cold War stand-off between West and East and had therefore fully earned their state funding. The reports exhibit an already established choreography for such border trips in ticking off some highlights such as divided roads and houses, making use of West German border guards as travel guides, and incorporating local expertise to harvest anecdotes about border incidents and life on the Cold War front line.

The individual visitor, however, who traveled on his or her own volition outside the framework of organized tours remains the unknown quantity of border travel despite the fact that, according to an intelligence report by GDR troops (1963), such individuals made up a large part of the border tourists.64 It appears likely that borderland residents took visitors to the border since it was one of the few attractions in those predominantly rural areas. Touring the border became almost an obligation if those visitors came from abroad. 23-year old Peter Boag, an American traveling Europe in the summer of 1984, stayed with a German family in Windsbach southeast of Nuremberg. Boag considered himself politically left-of-center and marveled at his host family’s admiration for President Ronald Reagan. As part of an outing, his German hosts drove Boag to the border at Neustadt near Coburg where the elaborate border fortifications with its ‘technological gizmos’ left a deep impression on him: ‘It was simply amazing the border patrol they have. Through binoculars I was able to look into the guard towers & I saw them looking right back at me with binoculars, & taking pictures of us w[ith] zoom lenses. They also took notes of our movements & perhaps of what we said – I [was told by the host family] that the whole area was bugged.’ Boag could not resist the temptation to step onto GDR territory, ‘so I can say I have been to East Germany’. Probably influenced by the way his host family introduced him to the border, Boag perceived the Iron Curtain as the dividing line between communism and freedom that was patroled by sinister looking border guards.65 Boag’s border experience of the mid-1980s was thus very much in line with the choreography of the 1960s school trips, suggesting that a code of conduct and perception along the border was established to a degree that, as Maren Ullrich’s research shows, it endured well beyond 1989.66

11![]()

The steady stream of visitors did not mean, however, that border communities were embracing this kind of tourism unequivocally. In the early 1950s, some local officials realized that the border could in fact be detrimental to leisure tourism. Resort towns (Kurorte) in particular did not want to see their image as sites of relaxation and recuperation intertwined with the dangers of the Iron Curtain. When the GDR introduced measures in June 1952 to seal the border, the Harz resorts on the western side felt the impact immediately. Fearful of an impending military clash, guests cancelled their reservations, reducing business in Hohe Geiß by 60 percent.67 The resort director of Braunlage even detected a ‘zonal border fear’ in the cancellation letters that amounted to a veritable ‘psychosis’.68 Officials in Goslar and Bad Harzburg struggled with the perception that their towns lay in the GDR.69 Such resort towns made an effort to downplay their proximity to the border in advertising materials and travel guides.

Even if local dignitaries considered it beneficial for the community to embrace border tourism, borderland residents did not necessarily play along. They complained about the sensationalist hype (Sensationsrummel) that these visitors brought to the area, especially if they arrived only to confirm their hinterland stereotypes about the ‘dangerous’ border. Near Breitensee in Bavaria, a team of American photo-journalists, for instance, planned to trigger some landmines on the eastern side of the demarcation line by throwing rocks across in order to capture such ‘realistic’ images on camera.70 Those communities that did welcome travelers whose explicit goal it was to see the Iron Curtain thus wanted to shape the tone and decorum of such visits. Local officials expected a certain earnestness from the border visitor; sensationalism was not welcome. Despite the hopes of local restaurateurs, the chief executive (Landrat) of Fulda county denounced ‘coffee trips to the zonal border with an ensuing dance event’ as bad taste. Companies advertising such trips, including federal rail (Bundesbahn), were chided for their lack of political tact.71 Indeed, the very term ‘tourism’ did not sit well with the Ministry of All-German Affairs. Ministry officials conceived of border trips as educational travel, not as ‘tourism’, a word that, in the mid-1960s, came to be associated with crowded beaches on the Mediterranean and thus implied ‘leisure’ and ‘consumption’.72

The people who had no voice in shaping border visits or impacting its decorum were, of course, the residents of border communities in the GDR. In the early years of partition, cross-border communication was still common. In the presence of border guards, however, pre-arranged forms of communications had to suffice, such as shaking out the bedding or a tablecloth at an open window as a form of waving or hanging up a colored garment on the clothesline to indicate news in the village.73 To the degree that family connections weakened over time, however, these subversive messages lost their meaning. After 1990, East German borderland residents reflected on the western tourists and, not surprisingly perhaps, related that they made them feel ‘angry because we were stared at like “monkeys in a cage”’.74 Indeed, common activities such as harvesting that would not have turned a head if occuring on western fields became a spectacle worth watching if conducted on eastern fields.75

12![]()

The reason why Western border communities put up with busloads of visitors and welcomed foreign dignitaries was a combination of a sense of political mission and obligation that came with living on the frontline of the Cold War and the desire not to be forgotten. Border residents increasingly developed a sense of living ‘in the butthole of the world’,76 in borderlands that were wrought with economic problems. A special federal program of borderland subsidies (Zonenrandförderung) pumped millions of Marks into these economically weak areas to stem infrastructural decline and demographic drain which the border was considered to have caused.77 But in many cases, political expediency collided with economic prudence. Long stretches of these borderlands proved beyond help because they had been economically weak even before the imposition of the border. In view of the larger economic problems of these newly peripheralized communities, the Iron Curtain held out the not unreasonable hope that tourism could provide some relief, that a first-time visit to inspect the division of the country would eventually translate into a longer-term visit to the borderlands, that the day-tripping sightseer would transform into a holiday maker, and that either way, the visitor would spend some money.

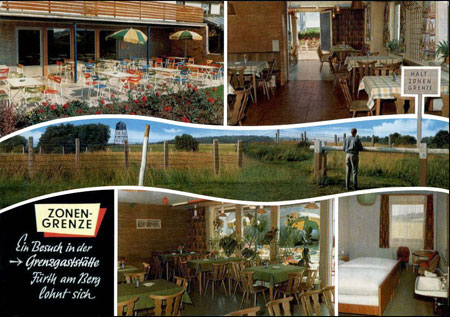

There is, however, conflicting evidence whether border tourism ever paid off for the municipalities, towns, and villages affected by it. In the mid-1960s, the mayor of Bergen-Dumme was confident that ‘of a hundred visitors to the local [border] information point, ten return for a vacation’.78 Similarly, members of the SPD group in the West German parliament concluded on a borderland visit to Lower Saxony in 1970 that ‘the distribution of travel parties to all border counties caused a considerable increase in the number of visitors to economically weak areas. As a consequence, there was a striking increase in tourism to those communities which led to notable economic advantages in several localities.’79 The innkeeper of the Border Inn (Grenzgasthof) Fürth am Berg, an establishment that incorporated the border into its name and advertising, thought in the early 1980s that he profited from the location. ‘People from Coburg and Neustadt found Fürth am Berg peaceful, remote and yet near enough for a day’s excursion.’80 The divided village of Zicherie, on the other hand, frequented by about 200,000 visitors per year, could not cash in on its popularity: ‘[The tourists] pull up in the free parking places beside the burgomaster’s house, walk to the border, read the placards, take some snapshots and drive away without spending a pfennig.’81

While the ultimate economic impact of border tourism in its various forms might thus be hard to pin down, it becomes apparent that federal and state investments in these regions were less about the bottom line and more about political appearance. These efforts were part of West Germany’s Cold War window dressing (Schaufensterpolitik) that aimed at highlighting the superiority of its economic and political system. Although the term ‘window dressing’ is often applied to the attractions of glittering West Berlin that were meant to make East Berlin and, by extension, the GDR look as gloomy and destitute as possible, similar efforts, albeit on a smaller scale, were undertaken in the borderlands. In conjunction with a regional tourism association, Hesse’s leading borderland official, Wilhelm Ziegler, pointed out that these regions and their inhabitants had an ‘all German’ duty. ‘The inhabitants of central Germany must get a view into a well-stocked display window that reveals the achievements of economic prosperity in the Federal Republic. The borderlands must not show any signs of poverty.’ Therefore, Ziegler considered investments in the tourist infrastructure well justified because tourism was not only believed to strengthen the local economy but ‘also had a political role to play’.82

13![]()

The construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 was a desperate push to force the political and spatial reorientation of East Germans towards their new state and its socialist order. The ensuing accommodation of GDR citizens to their now unavoidable situation has been widely noted in the literature.83 But the increasing fortification of the border not only forced a reorientation upon East Germans; both before and after 1961 it also supported a reciprocal process among West Germans, albeit in less drastic ways and under very different political circumstances. While historians have sought to understand the meaning and consequences of the Iron Curtain for the GDR and its citizens, they have not yet posed similar questions for the Federal Republic. This essay tries to open such a conversation in order to gauge the extent to which the border also affected West Germany, a state that related to the Iron Curtain first by demonizing it but eventually grudgingly accepting it as part of a new postwar reality, only to be baffled by its sudden disappearance. Analysis of the steady stream of visitors to the Iron Curtain offers one possible first step to flesh out an answer to these questions.

Most strongly during the late 1950s and 1960s, border tourism was framed variously as support for the East Germans behind the Iron Curtain or for the West Germans who now lived in economically depressed borderlands; as an accusation against the East German regime; and, ultimately, as a protest in favor of German unity. Border travel blended well with the widespread anti-Communism of the Federal Republic’s founding years. Partly a remnant of National Socialism’s anti-Bolshevism, partly a product of the Cold War stand-off, anti-Communism and the demarcation from the East German state provided some essential ideological glue and cohesion to West Germans and aided the Federal Republic in its integration into the Western Alliance.84 Border tourism was an ideal activity in this context. Seeing the border allowed West Germans and their visitors from abroad to juxtapose freedom and prosperity with captivity and decay, thus advertising the superiority of the capitalist model over its socialist other. As the East German leadership escalated border fortifications over the years and turned them into the military installation remembered today, a growing tourist infrastructure, including look-out platforms, information centers, and ubiquitous warning signs, accompanied these changes on the Western side. Border tourism thus stabilized the physical border in the sense that it developed a material infrastructure for border viewing. Border viewing, in turn, although undertaken or officially encouraged out of a whole range of different motives, inscribed the border on the mental maps of those who came to see it, regardless of whether the visitors came to condemn or just to ponder it. By traveling to the border to see for themselves where and how Germany and Europe were divided, visitors slowly adjusted to the fact that the border was there to stay and that half of the European continent was vanishing from view.85

Border tourism nonetheless remained a highly ambiguous phenomenon. In economic terms, it most likely did not meet the expectations and hopes that local communities and state officials had harbored for this sort of travel. Despite the common assumption that a border trip would inevitably translate into a condemnation of socialism and would help sustain various ties to and interest in East Germany, visits to the Iron Curtain failed to arrest the process of increasing accommodation to living in a divided country. At times, they amounted to a skewed form of communication between West and East Germany that reinscribed and reinforced mutual alienation. Indeed, a confrontation with the seemingly insurmountable border fortifications, especially in their most mature form of the late 1970s and 1980s, might well have supported a resigned response. Seeing the border and learning about its deeply layered structure conveyed the sense that it was intended for eternity. In fact, borderland residents themselves were among the first to acknowledge this new postwar reality.86

14![]()

The stream of visitors continued unabated until 1989, but the texture of border tourism changed over the years. By the early 1980s, communities along the border promoted their very remoteness, unindustrialized landscapes and nature as the main attraction, catering to visitors who wanted to get off the beaten track. Even the border travel guides issued by the states now highlighted the landscape as ‘special assets’ of the border region.87 Politically induced border tourism thus transmuted into leisure-oriented borderland tourism, a process that local officials had supported all along as they agreed for economic reasons to embrace the border on the edge of their community. By the 1980s, however, the selling point was less the military character of the Iron Curtain and more the borderlands themselves that the Curtain had created. In this shifted scenario, the border fortifications remained a sight to be seen, although, it seems, for different reasons. While the member states of the European Community strove to lower their internal borders, create Euro-Regions, and trade with ever fewer barriers, the border between East and West Germany stood as the counterpoint to integration and as an archetype of all borders. As the opportunities to experience ‘real’ borders were becoming increasingly blurred south of Munich, west of Aachen or north of Flensburg, the inter-German border remained a curiosity for West Germans even if it no longer had the shock value of earlier years.88

List of Archives:

BArch: Bundesarchiv

http://www.bundesarchiv.de

BayHStA: Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv

http://www.gda.bayern.de/archive/hauptstaatsarchiv

HHStAW: Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden

http://www.hauptstaatsarchiv.hessen.de

HStA Han: Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover

http://www.nla.niedersachsen.de/startseite/standorte/standort_hannover/standort-hannover-135671.html

1 Patrick Wright, Iron Curtain. From Stage to Cold War, Oxford 2007, traces the emergence of the Iron Curtain as political metaphor.

2 Tourism research has paid some attention to borders and borderland tourism. However, this relates to activities such as cross-border shopping, bordertown gambling, or the effects of formalities like visas for international travel. The border itself as a tourist destination is rarely discussed; see Dallen J. Timothy, Political Boundaries and Tourism. Borders as Tourist Attractions, in: Tourism Management 16 (1995), pp. 525-532, who identifies demarcation icons as worthy sights. The traces of the Berlin Wall and the former inter-German border have received attention as Cold War relicts for commemorative tourism and as memorial landscape. See Frederick Baker, The Berlin Wall. Production, Preservation and Consumption of a 20th Century Monument, in: Antiquity 67 (1993), pp. 709-733; Duncan Light, Gazing on Communism. Heritage Tourism and Post-Communist Identities in Germany, Hungary and Romania, in: Tourism Geographies 2 (2000), pp. 157-176; Keith R. Allen/Christian F. Ostermann, Interpreting the Physical Legacy of the Cold War. A Conference Report, in: Perspectives 42 (2004), pp. 81-91; Maren Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten. Erinnerungslandschaft deutsch-deutsche Grenze, Berlin 2006. Except for sections in Ullrich’s book and Yuliya Komska, Border Looking. The Cold War Visuality of the Sudeten German Expellees and its Afterlife, in: German Life and Letters 57 (2004), pp. 401-426, there is no work on tourism to the border before 1989. On the Berlin Wall as tourist attraction see Edgar Wolfrum, Die Mauer, in: Etienne François/Hagen Schulze (eds), Deutsche Erinnerungsorte, Vol. 1, Munich 2001, pp. 552-568.

3 On the West German side, the border was patrolled by members of the Federal Border Security (Bundesgrenzschutz, BGS), by customs officials (Zollgrenzdienst) and, in Bavaria alone, by a special border police (Grenzpolizei). For readability, I will use the generic term ‘border guards’ unless further specification is necessary.

4 See note 7 below.

5 The figures of border visitors were part of regular situation reports (Lageberichte) by the respective border regiments and divisions.

6 Besuch der Arbeitsgruppe Zonenrandgebiet der SPD-Bundestagsfraktion am 28./29. Mai 1970 im Zonengrenzbezirk Gifhorn-Lüchow Dannenberg, HHStAW Abt. 502, Bd. 1080. Klaus Hartwig Stoll, Das war die Grenze, Fulda 1997, p. 117, reports figures for the 150 km long stretch near Fulda: 100,000 people in 1964, 233,000 in 1965 and 358,000 in 1966.

7 Verzeichnis der Informationsstellen an der Grenze zur DDR. Stand: Januar 1979, HStA Han Nds. 380, Acc. 160/95 Nr. 1. During the same year, Lower Saxony reported an additional 90,800 visitors per month who stopped at outdoor information kiosks and panels. Since Bavaria, Hesse, and Schleswig-Holstein did not report visits to outdoor facilities, the actual number of border visitors may well have been much higher. On the other hand, the list cited here was compiled by the Federal Ministry for Inter-German Relations. The figures reported by the states must also be read as an administrative justification for the costs of maintaining the info centers.

8 Grenzkommando Nord, Aufklärungssammelberichte Dezember 1984 – November 1985, BArch GT 15466. Figures for the southern sector (Grenzkommando Süd) were not available.

9 Information on financial assistance can be found in the various border brochures and leaflets distributed by state agencies, such as the Federal Ministry for All-German Affairs (as of 1969 renamed Ministry for Inter-German Relations). See for example: Studienfahrten an die Demarkationslinie, ed. by the Federal Minister for Inter-German Relations, 1971, pp. 8-10, 67-68; Die innerdeutsche Grenze, ed. by the Federal Ministry for Inter-German Relations, 1987, p. 61.

10 Die innerdeutsche Grenze (fn. 9), p. 61.

11 On the green border situation, see Edith Sheffer, On Edge. Building the Border in East and West Germany, in: Central European History 40 (2007), pp. 307-339. Checkpoint inns are mentioned for Bergen-Dumme (Lower Saxony) in Rolf Brönstrup, Stacheldraht. Notizen und Mosaiken, Leer 1966, pp. 58-59; and for Obersuhl (Hesse) in Werner Roth, Dorf im Wandel. Struktur und Funktionssysteme einer hessischen Zonenrandgemeinde im sozial-kulturellen Wandel. Eine empirische Untersuchung, Frankfurt a.M. 1969, pp. 242-243.

12 On the deportations of GDR citizens from borderland communities, see Inge Bennewitz/Rainer Potratz, Zwangsaussiedlungen an der innerdeutschen Grenze. Analysen und Dokumente, Berlin 1994; Edith Sheffer, Burned Bridge. How East and West Germans Made the Iron Curtain, Ph.D. dissertation, Berkeley 2008, pp. 218-255.

13 The card is stamped on 7 November 1951. The traveler had most likely just crossed the green border and used the card to transmit news of his whereabouts.

14 Friedrich Christian Delius/Peter Joachim Lapp, Transit Westberlin. Erlebnisse im Zwischenraum, Berlin 1999; Axel Doßmann, ‘Stimmungsbarometer der Ost-West-Beziehungen’. Übertragungen auf deutschen Autobahnen um 1950, in: Archiv für Mediengeschichte 4 (2004), pp. 207-218; Creeping Crisis on the Autobahn, in: Life, 10 April 1950, pp. 21-22, 24.

15 It appears to be a trigonometrical tower for land surveying purposes, not an observation tower.

16 On the development of border fortifications see Peter Joachim Lapp/Jürgen Ritter, Die Grenze. Ein deutsches Bauwerk, Berlin 1997, 7th ed. 2009; Robert Lebegern, Zur Geschichte der Sperranlagen an der innerdeutschen Grenze 1945–1990, Erfurt 2002.

17 Gerhard Schätzlein/Reinhold Albert, Grenzerfahrungen. Bezirk Suhl – Bayern/Hessen zur Zeit der Wende, Hildburghausen 2005, p. 242.

18 Verena Winiwarter, Buying a Dream Come True, in: Rethinking History 5 (2001), pp. 451-454; Danielle M. Lasusa, Eiffel Tower Key Chains and Other Pieces of Reality. The Philosophy of Souvenirs, in: Philosophical Forum 38 (2007), pp. 271-287.

19 Lisa M. Brady, Life in the DMZ. Turning a Diplomatic Failure into an Environmental Success, in: Diplomatic History 32 (2008), pp. 585-611 (p. 608), displays a keychain from the DMZ, adding that South Korean entrepreneurs are ‘cashing in’ on the DMZ’s popularity with tourists. A similar tension exists in regard to mementos of the 11 September attacks and New York’s Ground Zero. See Marita Sturken, Tourists of History. Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero, Durham 2007. The book opens with reflections on a World Trade Center snow globe.

20 Malcolm Foley/J. John Lennon, JFK and Dark Tourism. A Fascination with Assassination, in: International Journal of Heritage Studies 2 (1996), pp. 198-211 (p. 198). Other terms for this phenomenon are ‘grief tourism’ and ‘disaster tourism’. The terms are used to cover battlefield, cemetery, prison, crime, slavery, and Holocaust tourism.

21 Foley/Lennon, Dark Tourism. The Attraction of Death and Disaster, London 2007, pp. 1-12, esp. 11; Richard Sharpley/Philip R. Stone, The Darker Side of Travel. The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism, Bristol 2009.

22 Jürgen H. Krenzer, Eßkultur und Agrarkultur – kulinarisches und gastliches Ereignis, in: Berichte zur ländlichen Entwicklung 82 (2004), pp. 39-44 (p. 39).

23 Heinrich Thies, Weit ist der Weg nach Zicherie. Die Geschichte eines geteilten Dorfes an der deutsch-deutschen Grenze, Hamburg 2005.

24 On the history of Mödlareuth, see the website of the border museum there at http://www.moedlareuth.de and the forthcoming dissertation ‘Dividing Mödlareuth. The Incorporation of Half a German Village into the GDR Regime, 1945–1989’ by Jason Johnson, Northwestern University.

25 Quote in: Der Kreistag an der Zonengrenze, in: Weilburger Tagblatt, 10 August 1965; David Shears, The Ugly Frontier, New York 1970, pp. 182-183; Elmar Clute-Simon/Reiner Emmerich, Das Haus auf der Grenze, Bad Hersfeld 1996. The eastern half of the building was returned to the owners in 1976 as a result of the work of the German-German border commission (Grenzkommission).

26 Die Flucht mit Lok 83, series beginning 8 September 1969, in: Bild; info on enterprising Helmstedters by Margrit Sterly, Director, Helmstedt Border Museum, June 2007.

27 Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten (fn. 2), pp. 95-98. The intelligence report of the East German border unit noted that buses continued to frequent the site daily. 7. Grenzbrigade, Aufklärungsbericht Oktober 1963, 11 November 1963, BArch DVH 32/117481.

28 Joachim Kleinmanns, Rheinische Aussichtstürme im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Kassel 1986, pp. 11-22; John Urry, The Tourist Gaze, London 2002, p. 32; Orvar Lèofgren, On Holiday. A History of Vacationing, Berkeley 1999, pp. 44-46.

29 ‘Die Aussichtsplattform ist mittels der in DDR-Richtung existierenden Fenster in bestimmte Blicksektoren eingeteilt. Diese Blicksektoren sind unterhalb eines jeden Fensters auf entspre-chendem Anschauungsmaterial erläutert und dienen dem Besucher als Einweiser über das einsehbare DDR-Territorium.’ Feindobjektakte ‘Thüringenblick’, BStU, Außenstelle Suhl, XI/584/84. I wish to thank Reinhold Albert, Sternberg, for sharing this file with me. See also NVA, 13. Grenzbrigade, Unterabteilung Aufklärung. 24 May 1963, BArch DVH 32/117432, for an intelligence report by GDR troops on the construction of the Lauenstein tower. It features a map projecting the viewing angle from the 26 meter high tower. The report predicted a 15 kilometer deep view into GDR territory.

30 The East German response to border tourism is discussed in Eckert, Zaun-Gäste. Die innerdeutsche Grenze als Touristenattraktion, in: Thomas Schwark/Detlef Schmiechen-Ackermann/Carl-Hans Hauptmeyer (eds), Grenzziehungen – Grenzerfahrungen – Grenzüberschreitungen. Die innerdeutsche Grenze 1945–1990, Hanover 2011, pp. 243-251.

31 Schätzlein/Albert, Grenzerfahrungen (fn. 17), p. 242.

32 Aussichtsturm verlor seine Bedeutung. Symbolträchtige Plattform abgerissen – Abbenröder setzen sich nun für KfZ-Übergang ein, in: Goslarsche Zeitung, 18 January 1990; Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten (fn. 2), p. 158.

33 See the report of the State Commissar for Borderlands in Hesse, Heinz Kreutzmann, Bericht über die Besichtigung von Informationszentren entlang der Zonengrenze in Niedersachsen, 6 August 1965, HHStAW Abt. 502, vol. 11108a.

34 Verzeichnis der Informationsstellen (fn. 7). Only Lower Saxony reported the number of outdoor information panels.

35 Kreutzmann, Bericht (fn. 33); Zonengrenzberatungsdienst Niedersachsen, Maßnahmen zur Förderung des Zonenrandbesuchs, 12 November 1965, HHStAW Abt. 502, vol. 11108a.

36 Brückner, Ministry for Federal Affairs in Lower Saxony, to Federal Ministry of the Interior, 20 February 1976, HStA Han Nds. 380, Acc. 160/95 Nr. 1.

37 Kleine, Oberkreisdirektor Helmstedt, to Ministry for Federal and European Affairs in Lower Saxony, 27 July 1983, HStA Han Nds 380, Acc. 160/95 Nr. 10; further correspondence ibid.

38 Grenzinformationszentren in Niedersachsen, no date (presumably 1986), HStA Han Nds. 380, Acc. 160/95 Nr. 2; Eröffnung der Informationsstelle ‘Grenze zur DDR’ in Tann/Rhön, 20 March 1987, HHStAW Abt. 531, vol. 175 (Druckschriftensammlung, 1980-89); Ministry for Federal and European Affairs in Lower Saxony to Bezirksregierung Braunschweig, 5 July 1988, HStA Han Nds. 120 Lüneburg, Acc. 160/95 Nr. 4.

39 Post-1989 commemorative tourism goes beyond the scope of this article. The re-dedication of the tourist infrastructure along the border and the emergence of a memorial landscape dedicated to German partition is the central topic of Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten (fn. 2). See also Anja Becker, Wie Gras über die Geschichte wächst. Orte der Erinnerung an der ehemaligen deutsch-deutschen Grenze, Berlin 2004.

40 Kurt von Gleichen, Die Grenznähe macht politisch aufgeweckter. Kleine Reise längs des Eisernen Vorhangs im Herbst 1951, in: Neue Zeitung (Frankfurt edition), 13 November 1951.

41 Voraus-Auszug aus der Niederschrift über die [Bayerische] Ministerratssitzung vom Dienstag, 3. Juli 1979, BayHStA, Bay. Staatskanzlei Nr. 19489. The Bavarian minister of the interior, Gerold Tandler, said that ‘border tours […] could serve as preventive measures against communist infiltration of our youth if the young people could see the conditions along the border to the GDR’.

42 Zonengrenze Bayern, ed. Bayerischer Staatsminister für Bundesangelegenheiten, no date [1970s?].

43 Zonengrenze Niedersachsen, ed. Niedersächsischer Minister für Bundesangelegenheiten, für Vertriebene und Flüchtlinge, 1966, p. 1.

44 Die Zonengrenzfahrt, ed. Hessische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 1964, pp. 2-4 (p. 3).

45 Zonengrenze Niedersachsen (fn. 43), p. 2. See also the 1968 edition, p. 2.

46 Die Grenze. Schleswig-Holsteins Landesgrenze zur DDR, ed. Innenminister des Landes Schleswig-Holstein, third edition 1985; Deutschland diesseits und jenseits der Grenze. Niedersachsen, ed. Niedersächsischer Minister für Bundesangelegenheiten, 1986; The Border Between Hesse and the GDR. Brief Information for Visitors, ed. Hessendienst der Staatskanzlei, 1986.

47 In the Heart of Germany – In the 20th Century, Bonn: Federal Ministry of All-German Affairs, 1960; En el Corazon de Alemania en Pleno Siglo XX. La Frontera con la Zona, Ministerio Federal para Asuntos de Toda Alemania Bonn y Berlin, 1965; Unmenschliche Grenze. Inhuman Frontier. Omänskliga Gränser, Hanover: Niedersächsische Landeszentrale für Heimatdienst, 1958. The first two titles are a version of the government publication ‘Mitten in Deutschland’. The Federal Ministry for Inter-German Relations also considered printing brochures in Italian and Turkish to cater to the increasing number of ‘guest workers’ among the border visitors. See Ministry to Information Points and Visitor Centers, 28 November 1974, HHStAW Abt. 502, vol. 7516b.

48 The Foreign Office cooperated with the governments of the states adjacent to the border. The state chancelleries developed the itineraries. A number of such itineraries and the coopera-tion with the Foreign Office are documented in HStA Han Nds. 50 Acc. 96/88 Nr. 156/1.

49 Delegation of the French European Movement, visit in February 1960, HStA Han Nds. 50 Acc. 96/88 Nr. 156/1.

50 Ibid. The MP was Edouard Rieunaud of the Movement Républicain Populaire (MRP), a Christian-democratic party that promoted French-German reconciliation.

51 Südamerikanische Bischöfe von der Zonengrenze erschüttert, in: Die Parole, 15 February 1964, p. 12.

52 State Chancellery, Ministerialrat Wittich, Memo on Zonengrenzfahrt on 9 July 1960, HStA Han Nds. 50 Acc. 96/88 Nr. 156/1; Dazu können wir nicht schweigen, in: Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung, 11 July 1960.

53 Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten (fn. 2), pp. 62-65 (p. 63); Pertti Ahonen, Victims of the Berlin Wall, 2006, http://www.soc.unitn.it/sus/attivita_del_dipartimento/convegni/maggio2006/gcabstracts/ahonen.htm.

54 Legationsrat I Junges, AA, Ref. 991, Aufzeichnung, Reise einer Delegation des Comité de Liaison de la Résistance durch Deutschland und nach Berlin, November 1959, HStA Han Nds. 50 Acc. 96/88 Nr. 156/2.

55 Halin was a Belgian socialist involved in sabotage during the German occupation. After the war, he became a professional resistance activist and an anti-communist militant. Pieter Lagrou, The Legacy of Nazi Occupation. Patriotic Memory and National Recovery in Western Europe, 1945–1965, Cambridge 2000, pp. 270, 282-284.

56 HStA Han Nds. 50 Acc. 96/88 Nr. 156/2.

57 In 1970, more than 25,000 West Germans traveled to Poland. In 1975, the number rose to 254,000. Many of these travelers were returning to the towns and villages from which they had fled at the end of World War II. The phenomenon is alternately called ‘roots tourism’, ‘heritage tourism’, ‘homeland tourism’, or Heimwehtourismus. One of the few articles on the phenomenon is Doris Stennert, ‘Reisen zum Wiedersehen und Neuerleben’. Aspekte des ‘Heimwehtourismus’ dargestellt am Beispiel der Grafschaft Glatzer, in: Kurt Dröge (ed.), Alltagskulturen zwischen Erinnerung und Geschichte. Beiträge zur Volkskunde der Deutschen in und aus dem östlichen Europa, Munich 1995, pp. 83-94; for figures see Miroslaw Ossowski, Ostpreußen in der deutschen Literatur nach 1945, in: Birgit Lermen/Miroslaw Ossowski (eds), Europa im Wandel. Literatur, Werte und europäische Identität, St. Augustin 2004, pp. 115-134 (p. 117). Ongoing work by Mateusz J. Hartwich (Frankfurt/Oder), Andrew T. Demshuk (Urbana-Champaign), and Corinna Felsch (Marburg) promises to illuminate the phenomenon of homeland tourism further.

58 Komska, Border Looking (fn. 2), p. 401. This article refers to the border with Czechoslovakia. See also Katharina Eisch, Grenze. Eine Ethnographie des bayerisch-böhmischen Grenzraums, Munich 1996, pp. 284-300.

59 Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten (fn. 2), pp. 50-54, 66-72 with images. On the West German discourse of expulsion and lost territories see Eva Hahn/Hans Henning Hahn, Flucht und Vertreibung, in: François/Schulze, Deutsche Erinnerungsorte (fn. 2), pp. 335-351.

60 Sepp Binder, Die Narbe der Nation. Zwischen Touristen und Tretminen, in: ZEIT, 13 June 1969, p. 8.

61 An der Zonengrenze. 325 Heimatvertriebene aus dem Untertaunuskreis am Stacheldraht, in: Hersfelder Zeitung, 13 May 1965. The article makes a point of noting that this group, arriving in eight buses, was the largest to visit the border in Hersfeld county thus far. On the East German reaction see: Regie führt der BGS, in: Der Grenzpolizist, 12 October 1961. See also: Bundesgrenzschutz als ‘Fremdenführer’ von Landsmannschaften, in: Grenzsoldat, 21 June 1962, p. 2.

62 Shears, Ugly Frontier (fn. 25), p. 100; the monthly intelligence reports of the GDR border troops list the number of visitors in civilian clothes and in uniform. See e.g. BArch GT 13647 (Grenzkommando Nord, Grenzaufklärungssammelberichte, März 1983 bis November 1984).

63 Unsere Fahrt an die Zonengrenze (1961); Staatspolitische Bildungswoche Bad Kissingen (1962); Unsere Fahrt in die Rhön (1969). All three scrapbooks are in the possession of the author.

64 NVA, 13. Grenzbrigade, Aufklärungssammelbericht, September 1963, BArch DVH 32/117480.

65 Peter Boag, personal journal, entry for 4 and 5 September 1984; in the possession of and cited with permission of the author. My sincere thanks to Prof. Boag for sharing these personal notes.

66 Ullrich, Geteilte Ansichten (fn. 2), pp. 33-34, 159-161, 292.

67 Gaststätten- und Fremdengewerbe des Harzluftkurortes Hohe Geiß an die Bundesregierung, Ausschuß für gesamtdeutsche Fragen, 30 June 30, HStA Han Nds. 500, Acc. 2/73 Nr. 376/5.

68 Kurdirektor Thiem, Kurbetriebsgesellschaft Braunlage/Harz to City Administration Braunlage/Harz, 16 June 1952, ibid. ‘Durch die zahlreichen Nachrichten in der Presse […] usw. sind viele verängstigte Gemüter, welche nach hier kommen wollen, derartig eingeschüchtert worden, daß sie unter Angabe von allen Gründen entweder von ihrer bisherigen Bestellung Abstand nehmen oder überhaupt nicht nach hier kommen wollen. So hat uns heute ein namhaftes Reisebüro aus Hannover geschrieben, daß […] die vorsprechenden Reiselustigen keinesfalls zu bekehren sind, weil sie Angst vor der Zonengrenze haben […]. Diese Grenzzonenangst hat eine Psychose hervorgerufen, welche sich mindestens für den Kurverkehr […] sehr ungünstig auswirkt.’

69 County of Wolfenbüttel to President of the Administrative District Braunschweig, 13 November 1950; City of Goslar to President of the Administrative District Braunschweig, 15 November 1950, ibid.

70 Binder, Die Narbe der Nation (fn. 60).

71 Quote in: Mobilisierung der Hilfen für das Zonenrandgebiet. Landrat Dr. Stieler fordert Planungen auf längere Sicht, in: Fuldaer Volkszeitung, 15 July 1964; on Bundesbahn see Stoll, Grenze (fn. 6), p. 120.

72 Heinz Kreutzmann, Bericht über die Sitzung der Zonenrandländer und Bonner Ministerien im Gesamtdeutschen Ministerium in Bonn bezügl. der Errichtung von Info- und Beratungsstellen für Zonengrenzfahrten, 23 December 1964, HHStAW Abt. 502, Bd. 11108a.

73 Daphne Berdahl, Where the World Ended. Re-Unification and Identity in the German Borderland, Berkeley 1999, pp. 64, 142; Jason Johnson, Living with the Border. Constructing the ‘Iron Curtain’ through a German Village, paper presented at the German Studies Association, 2009.

74 Claudia Schugg-Reheis/Michael Bahr, Grenzenlos. Thüringer und Franken schreiben über 45 Jahre Grenzdasein, Coburg 1992, p. 15.

75 Rolf Nobel, Mitten durch Deutschland. Reportage einer Grenzfahrt, Hamburg 1986, p. 191.

76 The Helmstedt border museum put on an exhibition commemorating 20 years of the border’s opening in 2009, featuring a poster with the text ‘40 Jahre am Arsch der Welt. Jetzt mitten in Deutschland’.

77 Gert Ritter/Joseph G. Hajdu, Die innerdeutsche Grenze, Köln 1982; Hans-Jörg Sander, Das Zonenrandgebiet, Köln 1988; Philip N. Jones/Trevor Wild, From Peripherality to New Centrality? Transformation of Germany’s Zonenrandgebiet, in: Geography 78 (1993), pp. 281-294; Jones/Wild, Opening the Frontier: Recent Spatial Impacts in the Former Inner-German Border Zone, in: Regional Studies 28 (1994), pp. 259-273.

78 Brönstrup, Stacheldraht (fn. 11), pp. 57-58. The number of overnight stays in Bergen rose from 2,500 in 1955 to over 10,000 in 1965, although there is no way of proving a connection between the information point and the rising number of guest-nights.

79 Besuch der Arbeitsgruppe Zonenrandgebiet (fn. 6).

80 Anthony Bailey, Along the Edge of the Forest. An Iron Curtain Journey, New York 1983, pp. 186-187.

81 Shears, Ugly Frontier (fn. 25), pp. 175-176.

82 Karl-H. Reccius, head of the tourist association for Kurhessen and Waldeck, to Ziegler, 19 November 1955, HHStAW Abt. 502, vol. 374. Correspondence in the file shows that the memo was instigated by Ziegler and represents his views and diction.

83 Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship. Inside the GDR 1949–1989, Oxford 1995, pp. 139-146, esp. 143; Patrick Major, Behind the Wall. East Germany and the Frontiers of Power, Oxford 2010, pp. 155-176; Corey Ross, East Germans and the Berlin Wall. Popular Opinion and Social Change before and after the Border Closure of August 1961, in: Journal of Contemporary History 39 (2004), pp. 25-43.

84 Patrick Major, The Death of the KPD. Communism and Anti-Communism in West Germany, 1945–1956, Oxford 1997, pp. 257-293; Eric D. Weitz, The Ever-Present Other. Communism in the Making of West Germany, in: Hanna Schissler (ed.), The Miracle Years. A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949–1968, Princeton 2001, pp. 219-232; Bernard Ludwig, La Propagande Anticommuniste en Allemagne Fédérale, in: Vingtième Siècle 80 (2003), pp. 33-42.

85 On the curious indifference of Western Europeans to the disappearance of Eastern Europe, see Tony Judt, Postwar. A History of Europe Since 1945, New York 2005, p. 196.

86 Roth, Dorf im Wandel (fn. 11), pp. 254, 302-304. This 1968 study of the town Obersuhl near Bebra in Hesse concludes that border residents neither felt particularly threatened by the border nor inspired to engage in political activism in order to overcome it.

87 ‘The peace and charm of its landscape and the hospitality of its people give it a high recreational value.’ The Border Between Hesse and the GDR. Brief Information for Visitors, ed. Hessendienst der Staatskanzlei, 1986, p. 2.

88 I wish to thank the Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung (ZZF) in Potsdam for a Leibniz Summer Fellowship as well as the Fox Center at Emory and Emory College for a Research Grant in Humanistic Inquiry. Both grants helped to make the research for this article possible.

![Group of visitors at the inter-German border, Mödlareuth (Bavaria), 1985/86

(Photo: Archive Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur [Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship], collection Uwe Gerig, picture 4809)](/sites/default/files/medien/static/2011-1/Eckert_Abb1.jpg)