- The German Language in Jewish Life before Hitler

- The Language of Hitler?

- A Nazi Language in Jerusalem

- Eichmann’s German

- Eichmann and other Germans

- Reading Hannah Arendt Hearing Eichmann’s German

- Conclusion

After the fall of Nazism, intellectuals and writers grappled with the idea – for some, the realization – that the German language had become a tainted language. Writers who had been nurtured by the German language from an early age and were drawn to it as a language of literary creativity mused in different ways on what it meant to remain anchored in the German language after its contamination through ›the thousand darknesses of murderous speech‹, as Paul Celan put it in 1958.1

The premise of this view is that languages are receptacles of history; that they carry the past as if it had been grafted onto them. As literary critic George Steiner put it in a 1960 essay on the decline of the German language, ›everything forgets, but not a language‹.2 But the mnemonic quality of language pertains not only to its most recent history; it is built up of many layers of memory. This proved to be particularly fraught in the case of the German language and its status in the postwar period, because German served not only as the language of the Nazi regime but also as a key language of Jewish culture and politics, indeed as the quintessential language of Jewish modernity. If a language does not forget, what happens when its various, at times conflicting, layers of historical memory resurface? In this article I will tackle this question through the example of the 1961 Eichmann trial and the encounter it involved between different forms of German.

As an officer in the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, RSHA), Adolf Eichmann planned and oversaw the systematic deportation of European Jews to concentration camps. After the war, he lived under a false identity in Argentina until 1960, when intelligence information enabled the State of Israel to apprehend him near Buenos Aires and bring him to trial.3 The Israeli government under David Ben-Gurion wished to imbue the trial with historical and political significance, demonstrating the magnitude of the destruction of European Jewry and exhibiting Israel’s commitment to bringing Nazi criminals to justice.

![Eichmann trial, April 1961: The Israeli police officer Avner Less (1916–1987), a German-Jewish émigré, explains an organizational chart of SS institutions. (Government Press Office [GPO] D407-136) Eichmann trial, April 1961: The Israeli police officer Avner Less (1916–1987), a German-Jewish émigré, explains an organizational chart of SS institutions. (Government Press Office [GPO] D407-136)](https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/static/2023-2/Volovici_2-23_Abb1.jpg?language=en)

a German-Jewish émigré, explains an organizational chart of SS institutions.

(Government Press Office [GPO] D407-136)

The Eichmann trial has been thoroughly studied by historians and legal and literary scholars, and has been presented as a turning point in the history of Holocaust memory in Israel, West Germany, and globally.4 Scholars have also pointed out the unprecedented quality of the trial in enhancing public attention to witnesses and especially to victims of Nazism.5 As one of the first trials to be partially transmitted on radio and television, the Eichmann trial gave the public a unique opportunity to observe the language, rhetoric, gestures, voices, and style of its protagonists. Coupled with the global fascination with the event, the trial acquired features of a theatrical performance, a spectacle. This theme, too, has been studied widely.6

One key element informing the performative and audience-oriented characteristics of the trial is the fact that it was a multilingual event in which the German language played a central role. In what follows I will argue that the Eichmann trial brought to the surface historical tensions around the postwar status of the German language. More concretely, I will show that the German heard in the courtroom both affirmed and defied notions of German as a Nazi language. Eichmann’s German did not impress the listeners as the language of a fanatic architect of mass murder. In fact, observers and reporters hearing Eichmann conceded that his language was marked by its mixture of technocratic tediousness, emotionlessness, and confusion. These brought to the fore not only the Nazification of German, but also older ideas concerning German cumbersome technical style. The trial thus situated ›Nazi German‹ within longer historical trajectories of thinking about German.

Moreover, during the trial several suppressed and forgotten historical functions of the German language were given a major national and international platform. Arguably the most crucial among them was the function of German as a language of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. The points of contact and the differences between the German used by the trial’s various protagonists – the defendant, the judges, the prosecutor, and the witnesses – helped to dispel the idea of German as a tainted language.

Insofar as the German heard in the courtroom received historiographical scrutiny, it tended to be viewed through the lens of Hannah Arendt’s 1963 work Eichmann in Jerusalem and particularly her depiction of Eichmann’s language as indicative of the specific mindset which dictated his actions. However, Arendt’s perspective on Eichmann’s language also needs to be historicized since it drew on historically contingent perceptions of language and of the German language in particular. This article will situate Arendt’s work within pre-war Jewish language politics and consider its postwar echoes.

I will begin by overviewing the role of German in modern Jewish history and the various historical, political, and religious sensitivities it carried. I will show that the postwar perception of German as a tainted language built on longer trajectories of engagement with German. I will then turn to the Eichmann trial and, drawing on contemporary press reports, trial protocols and footage, as well as archival materials, will delve into the various questions and dilemmas that the appearance of the Nazi language in Jerusalem generated for the trial’s protagonists, its audience, its reporters, and for intellectuals assessing the trial’s meaning.

1. The German Language in Jewish Life before Hitler

In his opening speech at the Eichmann trial, the Israeli state prosecutor Gideon Hausner offered a glimpse into the heavy weight that the German language had carried in the history of Jews. Ashkenaz [i.e., Germany], he said, ›was the land in which the Jew experienced more suffering than anywhere else. And yet, the Jewish people nourished tremendous affection for it. Its popular language, Yiddish, was created on the basis of the German language, and Jews took it with them across the Diaspora, to Poland, to Russia, and overseas.‹ Hausner’s narrative also pointed to the cardinal importance of German as a language of Jewish modernity and as a foundational language for the Zionist movement. ›In the German language the classic literature of Herzl was created, it was spoken in the Zionist Congress, it was the language in which the masterpieces of Jewish thought and history were written.‹7 Hausner then underlined Jews’ contribution to German culture and literature, which had instilled in them a sense of pride and belonging to German culture. Hausner’s narrative was aimed at conveying the historical drama which the trial was about to present. The symbolic heirs and representatives of the betrayed victims of Germany were now seeking historical justice.

This framing involved a certain tension around the matter of language. Indeed, that the German language was about to be heard during the Jerusalem trial was not a mere technical detail. Across the Jewish world, German occupied the status of a forbidden language. In Israel in the 1950s, state institutions tried to minimize, and at times to forbid, the use of the language in official venues such as cinemas, theatres, music halls, and radio stations. The various justifications used for this informal boycott were all similar in nature: it seemed morally inappropriate, if not obscene, for the state of the Jews to allow German to be used as if it were an ordinary language and not a language of Jewish death.

One problem with this approach was that before the Holocaust, the presence of German in Jewish diasporic life was profound.8 Since the eighteenth century, German had been associated with processes of social change in Jewish communities within and beyond German-speaking lands. Lying at the heart of state reforms in German principalities and the Habsburg Empire, Jews’ acquisition of High German at the expense of Yiddish was considered a crucial prerequisite for Jewish emancipation and ›civic improvement‹. Jews were encouraged – often compelled – to master German and send their children to German-language schools as a means of becoming productive citizens. The acquisition of German was not merely the result of political pressure from the state, but also a response to pressure from within Jewish communities. The German Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) of the late eighteenth century laid profound emphasis on the learning of German as a matter of both practical and moral importance. The idea of German as a ›pure language‹ was vital to this perception, in particular owing to the prevalent image of Yiddish as ›distorted German‹.9 The flourishing of a Germanophone Jewish culture in the realm of scholarship, literature and science became an essential aspect of German Jewish self-understanding, a highly regarded and deeply contentious model of Jewish emancipation.

German’s status as a language of Jewish modernity also became a matter of political dissent within Jewish communities. German facilitated the acquisition of universal and secular knowledge, and therefore represented for many Eastern European Jews the danger of withdrawal from Jewish religious tradition. Jewish political activists – especially nationalists and socialists – also frequently targeted German Jews for their liberal proclivities and lack of political self-assertion. In this context, German represented Jews’ voluntary submission to the state’s linguistic policies at the expense of Jewish languages. As Galician writer and Jewish nationalist activist Yehuda Leib Landa argued in 1895, the German Haskalah taught in Hebrew and praised it, ›but for what purpose? Only to reduce the number of readers in this language and to crown in its stead the superior language in their eyes, the language of enlightenment, the language of the greatest poets, the German language.‹10

Moreover, antisemitic agitation in nineteenth-century Germany often raised the accusation that Jews’ relation to the German language was artificial and foreign.11 Some writers depicted the German spoken by Jews as stained by their ineradicable alienness. Richard Wagner remarked in an infamous 1850 essay that ›The Jew speaks the language of the nation in which he lives from generation to generation, but he always speaks it as a foreigner.‹12 At a time when visual markers distinguishing German Jews from non-Jews were virtually absent, constructing linguistic difference remained an effective means by which to designate Jews’ otherness. With the rise of German political antisemitism in the 1870s and 1880s, the idea took hold in Jewish nationalist circles that German was not only an esteemed language of culture, but also a vehicle of antisemitic hatred.

This duality reached a peak when, beginning in the 1880s, Jewish nationalists in Central and Eastern Europe identified the value of using German to advance the Jewish nationalist cause. The most prominent example of this trend was the anonymous 1882 pamphlet ›Auto-Emancipation! An Appeal to His People by a Russian Jew‹, published in German by the Russian Jewish doctor Leon Pinsker in the wake of anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Pale of Settlement. In 1884, the prominent Yiddish writer Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh (known by his pen name Mendele Moykher Sforim) translated ›Auto-Emancipation!‹ into Yiddish and wrote in his preface that the pamphlet had been written in German, ›the language of the people whose renowned intellectuals’ wisdom and humaneness is as great as the madness and evil of its truculent fools‹.13

The practical value of German in Jewish nationalist affairs grew further in the 1890s, when Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau established the Zionist movement. Essentially a Germanophone movement, its headquarters were located in German and Austrian cities, and its main periodicals and literature were published in German. The Zionist congress was conducted primarily in German, though the communication difficulties emerging between German speakers and Yiddish speakers hovered above the congress. It saw the emergence of Kongressdeutsch, a mixture of German and Yiddish which facilitated oral communication between Zionist delegates from across the Jewish Diaspora. Until 1935, the congress’s protocols were published exclusively in German.14

A certain discomfort with the centrality of German in Jewish nationalism figured in various political quarrels within the Zionist movement over the movement’s cultural ideology. For many critics of Herzl’s Zionism, the movement was acutely lacking a genuine commitment to Hebrew culture and to its role in the development of modern Jewish nationhood. The Germano-centric orientation of many Zionist leaders since Herzl was interpreted by critics such as Asher Ginsberg (Ahad Ha-Am) as a symptom of Western Zionists’ shallow notion of Judaism itself, a marker of an assimilatory and submissive approach to Western culture. For Jewish nationalists, as for earlier critics of various strands of the Jewish Enlightenment, German encapsulated both the allure and the danger of Jewish emancipation.

With the rise to power of the Nazi party, symbolic associations attached to German as a dangerous language became more sinister. From 1933, the Jewish community in Palestine (Yishuv) saw the arrival of about seventy thousand Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria, most of whom lacked a working knowledge of Hebrew. Jews escaping Hitler’s Germany were received with mixed sentiments by the established segments of the Yishuv. While the incoming immigrants enhanced the Yishuv’s size, boosted its economy, and included a significant number of highly educated individuals, they were often portrayed as profoundly rooted in German culture and insufficiently committed to Zionism. It was commonly alleged that they were the group of immigrants most resistant to adopting Hebrew.15 In May 1933, for example, the Zionist activist Eliezer Yaffe described the German immigration as ›a great danger to our revival movement: they might settle in their own neighborhoods, conducting the lives they had had in the »Vaterland« that threw them away […], and they might indeed establish German schools, publish German newspapers, and preach for assimilation.‹16

In 1935, the right-wing Hebrew newspaper Do’ar Hayom published an essay admitting that the monolingual aspiration of Hebraism had failed to materialize. ›Walk in the streets of our land, and especially in Jerusalem, and you will hear an unwarranted mixture of tongues.‹ The reporter counted the different languages he could hear on the bus from Haifa to Jerusalem (Hebrew, Arabic, English, and German), and added a warning: ›I believe that through the spoken and publicly-read German the Yiddish language will sneak into our camp. From within the walls of spoken German in this land I can smell the scent of Yiddish.‹ In Haifa, in particular, ›the sound of the language of Hitler is heard in all its accents‹.17 Hebraists seeking to question the legitimacy of Yiddish as a national language could now remind the public that Yiddish had Germanic roots and was as such affiliated with the language of the enemy.

A counterargument to anti-German rhetoric appeared in January 1940 in Davar, the official newspaper of Mapai, the leading and left-leaning party in the Yishuv. Dov Sadan, the editor of the literary supplement, opposed the argument that ›German is the language of our enemy‹. He wondered whether this fact should matter at all from the Hebraist perspective, given that English and French, which were by no means the languages of the enemy, were equally problematic for anyone seeking to promote Hebrew culture and language in Palestine.

Moreover, Sadan believed that fighting the German language was in fact an attack on some of the foundations of modern culture, of Jewish culture, and of Zionism itself. ›German is the language of Kant and Hegel, without which our present thought is inconceivable; it is also the language of Schiller and Goethe, without which our present poetry is inconceivable; it is the language of defenders of truth and humanists, and lovers of Israel in particular, from Lessing to Thomas Mann; and it is also the language of our own – of Börne and Heine, of Lassalle and Hess, of Zunz and Graetz, of Herzl and Nordau, of Freud and Einstein.‹18

The question of whether it was possible to consider the various connotations of German in isolation from one another was tackled directly in September 1944, when the committee of a translation award sponsored by the city council of Tel Aviv failed to reach a decision, and canceled the prize for that year. It soon transpired that the committee disagreed on whether to award the prize to a new Hebrew version of Goethe’s Faust. The committee’s stance was that the time was not appropriate for discussing a classic German literary work for the purpose of awarding a prize.19

The cancellation was received with both praise and dissent. For those who supported the committee’s decision, it confirmed the view that the persecution of Jews by the Third Reich implicated German culture in its entirety. One writer asserted that for persons of Jewish descent to ›be able to enjoy the creativity of the German nation, whether in word, sound, or color [was] a clear sign of a certain flaw in their soul‹.20 Immigrants from Germany and Austria should likewise be expected to ›uproot their fondness for this damned nation and its culture, to expel its language from their mouths, to remove its authors from their bookshelves, to detest its poetry‹. Another columnist questioned the ›strange‹ muse that befell the translators, inspiring them to translate Goethe’s Faust while Hitler’s country was killing the Jewish people.21

Such a stance did not, however, go uncontested. One commentator from the left-leaning journal Al Ha-Mishmar asked: ›Should Goethe pay for the sins of Hitler? It is unthinkable that experts of Hebrew literature would choose to take revenge on our behalf in this manner.‹22 Ultimately, the anti-German approach prevailed. In 1945, the committee met again, this time deciding to give the prize to a translation from Yiddish into Hebrew.

The historical record suggests that after 1933, Hebraists of different political orientations took up the idea of German as the language of Hitler to advance their cause.23 This is not to say that the rise of Nazism did not have a genuinely shocking impact on Jews in Palestine and elsewhere, turning German into a language that was linked with Nazi brutality. However, the affective response cannot fully explain the immediate appearance of the equation of Hitler with the German language, or its integration with earlier discursive legacies concerning German’s detrimental impact on Jewish society. Associating German with Hitler served at times as a polemical vehicle in Jewish nationalists’ language disputes, marking a new stage in efforts to present it as problematic, if not illegitimate, for Jews to use German.

Notwithstanding the informal anti-German boycott, several steps were made in the first years of Israel’s existence towards the normalization of relations between Israel and West Germany.24 On 10 September 1952, the two governments signed a reparations agreement in Luxemburg. Chancellor Konrad Adenauer headed the German delegation to the ceremony; the Israeli delegation was led by Moshe Sharett, Israel’s Russian-born Minister of Foreign Affairs. The following day, Sharett gave a short statement on the agreement and on his meeting with Adenauer. He concluded with the following words: ›In my conversation with Dr. Adenauer, we discussed the chasm separating our two peoples in view of what happened. The conversation was conducted in German. Not in Hitler’s German, but in the language of Goethe, a language we had both learned before Hitler’s rise to power.‹25

Sharett was born in the Russian Pale of Settlement, immigrated to Ottoman Palestine at the age of 12, had not spent any extended period in a German-speaking country, and learned German at home and at the high school he attended in Herzliya. As a Zionist politician, German was an integral part of his social landscape. His cautious words convey a realization that German had become a tainted language. He seems to have been aware that the image of an Israeli politician speaking to a German politician in German might evoke among Israelis a sense of discomfort or anger, and so he attempted to alleviate these feelings.

The reparations agreement and several collaborations in the realms of education and science contributed to a gradual relaxation of the anti-German boycott. In September 1959, a furor arose in the Hebrew media over the decision of Kol Ha-Musika, the Israeli classical music radio station, to play pieces sung in German. A columnist protested the decision, saying it might offend many Israelis. In a letter to Davar, Prague-born Israeli philosopher Hugo Bergmann responded: ›I would like to note that there are in Israel also people for whom declaring a boycott on a language – on the language in which Goethe and Herzl thought and wrote, in which the Zionist congresses were held until the establishment of Israel – generates a feeling of shame and disgrace. Kol Ha-Musika should consider these people’s feelings too.‹26 Bergmann’s letter evoked several critical responses, including one from the acclaimed essayist and poet Nathan Alterman. The latter argued that it was reasonable for members of the Jewish people to be particularly sensitive to a language whose words ›were used until not so long ago for the task of exterminating the Jews‹.27 Alterman’s words captured the state’s general approach to this matter until the early 1960s.

3. A Nazi Language in Jerusalem

The near absence of German from the Israeli public sphere came to an end with the 1961 Eichmann trial. Parts of the trial were transmitted live on radio, and video segments were shown in cinemas (television had not yet been introduced into the country).28 The event received extensive coverage and gripped Israeli society and the Jewish world from the beginning of the trial in April 1961 until Eichmann’s execution on 1 June 1962.29

One major practical challenge in the conduct of the trial concerned the administration of the languages spoken in it. The Jerusalem District Court stated, ›The Eichmann trial will be conducted in the Hebrew language‹,30 but participants used several languages, including English, German, and Yiddish. A team of ten interpreters was assembled, and the trial’s proceedings were translated in real time into German, French, English, and Hebrew. A daily transcript of the proceedings was distributed in all four languages.31

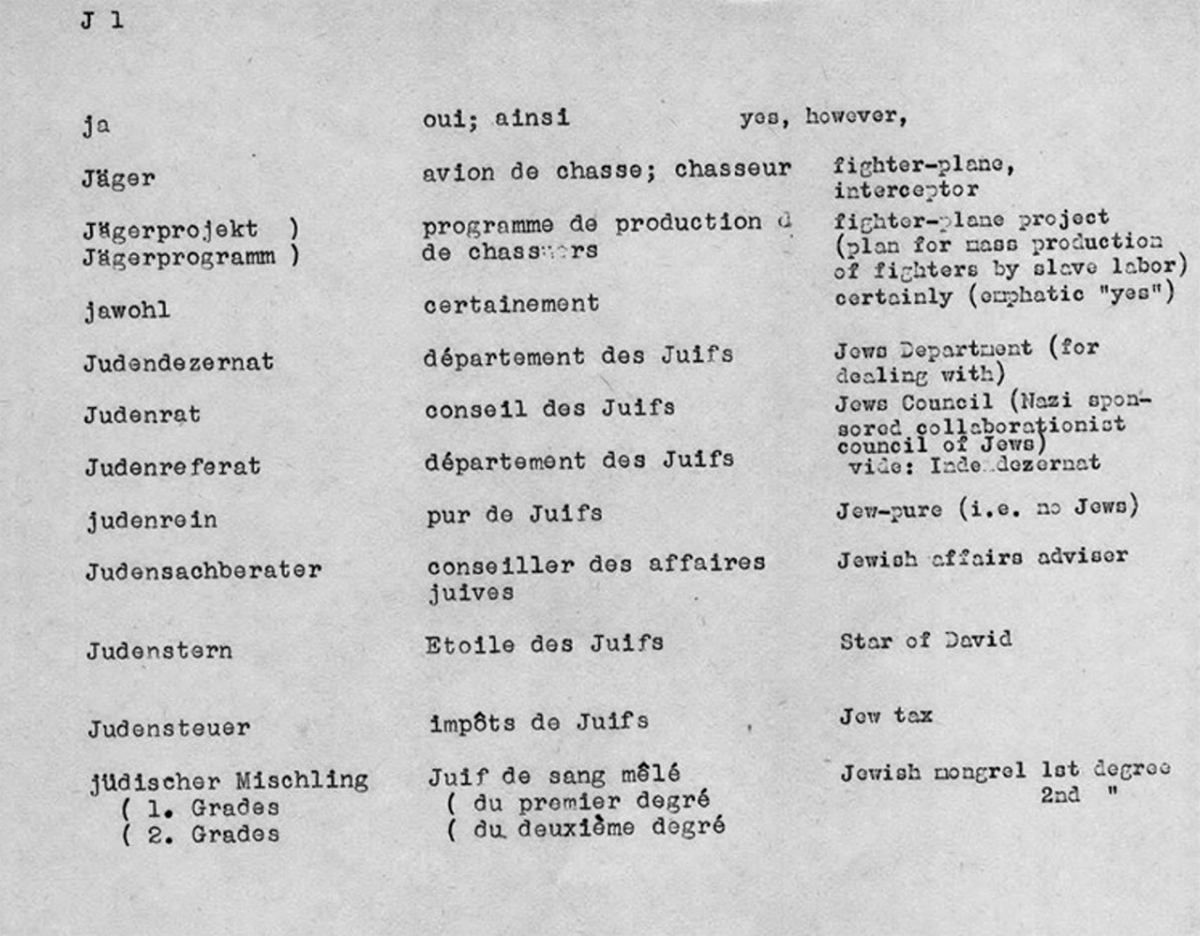

Both in its symbolic significance and in practical terms, German was central to the conduct of the trial and to the efforts to prove Eichmann’s guilt. However, the language appearing in Nazi administrative documents first required a good deal of clarification. Bureau 06, a special unit entrusted with the investigation of Eichmann, recruited German-speaking officers to undertake the investigation, with eleven of them working on the translation and analysis of German documents.32 The unit also employed civilians and volunteers to assist in the translation effort.33 Several officers were tasked with preparing a glossary of German terms with Hebrew translations.

![Excerpt from a glossary of German terms appearing in documents from the Nazi period, and their suggested Hebrew translations. The glossary was prepared by the translation team of Bureau 06. (Glossary of expressions, concepts, and special terms, designed to facilitate the uniform translation of the body of evidence in the German language, ed. by Commander Pinhas Dayan [Milon nivim, munahim u’vituyim meyuhadim: le-hakalat tirgumo he-ahid shel homer ha-re’ayot ba’safa ha-germanit], Bureau 06, Israel Police; National Library of Israel, 2 = 2017 A 14959) Excerpt from a glossary of German terms appearing in documents from the Nazi period, and their suggested Hebrew translations. The glossary was prepared by the translation team of Bureau 06. (Glossary of expressions, concepts, and special terms, designed to facilitate the uniform translation of the body of evidence in the German language, ed. by Commander Pinhas Dayan [Milon nivim, munahim u’vituyim meyuhadim: le-hakalat tirgumo he-ahid shel homer ha-re’ayot ba’safa ha-germanit], Bureau 06, Israel Police; National Library of Israel, 2 = 2017 A 14959)](https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/static/2023-2/Volovici_2-23_Abb2.jpg?language=en)

Nazi period, and their suggested Hebrew translations.

The glossary was prepared by the translation team of Bureau 06.

(Glossary of expressions, concepts, and special terms, designed to facilitate the uniform translation of the body of evidence in the German language,

ed. by Commander Pinhas Dayan [Milon nivim, munahim u’vituyim meyuhadim:

le-hakalat tirgumo he-ahid shel homer ha-re’ayot ba’safa ha-germanit],

Bureau 06, Israel Police; National Library of Israel, 2 = 2017 A 14959)

Most of this 60-some page glossary was dedicated to bureaucratic and technical terms, but it also offered translations of various euphemisms such as Arisierung (Aryanization), Blutschutzgesetz (Law for the protection of blood), Bereinigung des Judenproblems (settlement of the Jewish problem), Zwangssterilisierung (forced sterilization), Untermenschentum (sub-humanness), Entjudung (de-judaization), and Eindeutschung (Germanization). The translations were by and large literal, though in several cases the translators took some liberty. For example, the German term Ahnenerbe (Ancestral heritage), which was the name of a Nazi movement promoting racial doctrines, was translated into Hebrew as moreshet avot, a term with a strong religious connotation. Shalom Rosenfeld, who covered the trial for Maariv, noted after examining the glossary that the various entries reveal ›the pompous, Teutonic, arrogant, threatening terminology that the sick Nazi mind invented in the days of great darkness of the German culture and the German language‹.34

Bureau 06 also produced a German-French-English glossary. It was designed to facilitate the interpreters’ work throughout the investigation and during the trial. The English-language foreword to the glossary stated: ›When translating Nazi terminology, one must bear in mind that this language has a most specific sound and nature, but cannot be considered as educated German. Not to take these characteristics into consideration would introduce an element of forgery. In most cases this language has been coined by »Teutonic cranks«, »Deutschtümler« etc. It is designed to convey emotion by a choice of archaic, pompous and colourful terminology, and was meant to create a feeling of strength in its listeners and users. It is, of course, difficult to render such expressions into English, but the attempt must be and has been made in this glossary. It must be further remembered that the majority of the Nazi leaders came from low social strata; they were, in fact, riff-raff, and Winston Churchill’s description of Hitler as a »bloodthirsty guttersnipe« got close to the truth. They made up for their lack of education by latching on to impressive-sounding words, which were frequently linguistic monstrosities. It must be stated that this glossary is not yet perfect and changes are being made in accordance with increased understanding.‹35

Nazi terms and expressions prepared by Bureau 06

(Eichmann Trial Administration: Glossary: German – French – English,

23 March 1961, ETH Zürich, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, NL Avner W Less / 51)

While this glossary is an internal document aimed at facilitating the work of the police and prosecution teams, the historical comments made in this foreword are noteworthy. They echo a conversation between linguists and philologists about the nature of the Nazification of German. Much like Victor Klemperer’s LTI,36 the police document viewed Nazi German as a brutal deviation from proper, educated German. It also posited – somewhat inaccurately – that most Nazi leaders were uneducated. A different interpretation, put forward by George Steiner, described Nazis as making use of the German language’s militaristic and technocratic resources, which had been reverberating in the language long before Nazism rose to power.37 The question of how Nazi language should be grasped then opened up a broader question about continuities and discontinuities between modern German culture and the Nazi era.38 The position of the Israeli police, as captured in this document, was to defend the image of German culture and set it apart from Nazism.

During the trial itself, Nazi language figured frequently in exchanges between Eichmann and the prosecutors over the meaning and use of particular words. It was indeed the prosecutors’ goal to prove beyond any reasonable doubt that Nazi terms – as they appeared in the pertinent documentation and in the defendant’s own testimony – indicated Eichmann’s premeditated effort to coordinate the mass killing of European Jews. In one session, Eichmann was asked to clarify the meaning of Sonderbehandlung (special treatment), a term that appeared in a document with his signature.39 Eichmann denied that the term stood for killing, insisting that it had different meanings, including nonlethal ones, such as ›Germanization‹ of ethnic Poles.40 Elsewhere Eichmann argued that the words Vernichtung (annihilation) and Ausrottung (eradication) as used by Hitler and the Nazi regime in 1939 did not denote the physical but merely the political destruction of Judaism.41 When referring to the systematic impoverishing of Viennese Jews, the prosecutor focused on Eichmann’s use of the term entkapitalisieren (decapitalize).42 In another session, the meaning of the term Endlösung (Final Solution) as it had been used in 1941 was the subject of an exchange between Hausner and Eichmann, with the latter claiming that it had denoted deportation to Madagascar, not systematic killing.43 Hausner also asked Eichmann to clarify what Umsiedlung (resettlement) and Evakuierung (evacuation) denoted in various documents.44 Those listening to the trial were thus introduced to the significance of Nazi terminology and linguistic concealment for the planning and practice of destroying European Jewry.

![Gideon Hausner (1915–1990), chief prosecutor at the Eichmann trial, during cross-examination of the defendant, July 1961 (Government Press Office [GPO] D409-075) Gideon Hausner (1915–1990), chief prosecutor at the Eichmann trial, during cross-examination of the defendant, July 1961 (Government Press Office [GPO] D409-075)](https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/static/2023-2/Volovici_2-23_Abb4.jpg?language=en)

during cross-examination of the defendant, July 1961

(Government Press Office [GPO] D409-075)

Matters of terminology were also addressed extensively in the testimonies of witnesses, who spoke of the language used by Nazis in the ghettos and the camps, as well as the slang developed by those interned there. Yehiel Dinur, an Auschwitz survivor, described himself as one who had been a Muselman in the camp, a term coined by inmates in Auschwitz to describe prisoners who were no longer able to stand on their feet and respond to reality; walking dead, whose crawling resembled a praying Muslim.45 Other testimonies introduced listeners to terms specific to the Nazi management of deportations and concentration camps, such as Kinderblock (children’s block), Familienlager (family camp), Strafkommando (policing unit), and Blockälteste (block elder).46 Such terms had already been introduced to readers of historiography of the Holocaust and used in literature produced by Holocaust survivors,47 but the trial brought the Nazi language in an auditory form to a mass audience.

The language used by Holocaust survivors mattered in another respect also. One assumption underlying the idea of the Nazi language is that it was fundamentally distant from the victims of Nazism. Indeed, the very ability to boycott the German language after the Holocaust relied on the readiness to regard its function as the language of the murderers as outweighing all other functions it had had in historical memory. But the language used by Holocaust survivors, above all Yiddish speakers, had been in contact with Nazi German. Several Yiddish lexicons and glossaries appeared in the wake of the Holocaust, taking stock of new terms and of the changes that Yiddish had undergone during the war in ghettos and camps. The linguistic contact with the German language – and specifically with Nazi terminology – during the war period was significant in this context,48 and some testimonies of Eastern European Jews indeed conveyed a more pragmatic approach to language choices. The testimony of Zindel Grynszpan, whose son, Herschel, had assassinated a Nazi official in Paris in 1938, provides one example of this. He was asked whether he would prefer to give his testimony in German or Yiddish. A Polish-born Orthodox Jew, Grynszpan said that it made no difference to him: whether he spoke the language of the Nazis or the language of the Jews was of no consequential importance. He eventually decided to testify in German, though his testimony mirrored the fluidity that often existed between Yiddish and German in the lived reality of Ashkenazi Jews before the Holocaust. The status of German as a tainted language, the language of the murderers, bore less importance when stripped of its political uses.

The Eichmann trial gave a Nazi official the opportunity to plead for his innocence in his own voice using his own words. For the interpreters, this posed a significant challenge. The head of the team of interpreters, Lviv-born Adam Richter, arranged a two-week intensive training course, during which the interpreters read historical documents from the Third Reich as well as the protocols of the 1945–46 Nuremberg trials. In one training session, the interpreters were asked to hear recordings of Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the RSHA, and of Dieter Wisliceny, one of Eichmann’s deputies, in order to familiarize themselves with the linguistic style of Nazi officials.49

The unmediated encounter with Eichmann’s language initially had a somewhat shocking effect. The first Israeli to communicate with Eichmann was Avner (Werner) Less, a police officer who was born in Berlin in 1916 and left it in 1933. From 1951 he worked as an investigator of economic crime, and in 1960 he was recruited by the head of Bureau 06 to lead the interrogation of Eichmann. In a notebook written in May 1960, Less vividly depicted his encounter with Eichmann and his language: ›I turn on the tape recorder and ask Eichmann to start with his CV. And Eichmann begins to speak. It is as if a floodgate opened. I can feel how eagerly he had waited to finally be allowed to speak. His sentences are terribly long, it isn’t easy to follow him. His German is strange, a mixture of Berlin and Austrian accents, and he is using expressions and syntax forms that are entirely foreign to me. His way of speaking belongs to a different Germany, a Germany that took shape after 1933.‹50

Eichmann’s voice in the courtroom fascinated the audience. When he responded to the first question concerning his guilt – Im Sinne der Anklage, nicht schuldig (not guilty as charged) – reporter Shalom Rosenfeld transcribed the German words into Hebrew letters, noting the ›serenity, monotonous tone, with only the word »nicht« being emphasized‹.51 The front headline of the popular daily Yedioth Ahronot read: ›Are you Adolf Eichmann? The defendant stood at attention and replied: »Jawohl«.‹52 Another commentator noted that ›the German language was heard here, and it was heard also there. In the camps. In the ghettos. How strange.‹53 Shabtai Teveth, writing for Haaretz, noted, however, that the moment was anti-climactic in that it normalized Eichmann: ›And suddenly it appeared that the shocking and the inconceivable has turned into a presence that speaks in the language of humans. From now on the interaction is to be conducted using normal words, all of which could be found in a dictionary.‹54

Moshe Tavor, an officer in the Israeli Secret Services who took part in the operation in Argentina and served during the trial as commentator for Davar, noticed the proximity between Eichmann and Hitler’s German as it emerged from the recorded interrogation: ›The same Viennese dialect, the same mixture of typical Austrian vocabulary and Nazi jargon, the same rolling »r« – in short, the voice of his master.‹55 Two days later, Tavor wrote that Eichmann’s use of the verb verkraften, denoting the administrative ability to ›process‹ the deportations of the hundreds of thousands of Jews, revealed Eichmann’s rootedness in ›the vocabulary of the SS and the Gestapo‹.56 Tavor noted that ›Eichmann’s vocabulary is taken to a large degree from the vocabulary of the Nazis‹.57

![Eichmann in Jerusalem, July 1961: ›Eichmann continues to think in the categories of the Nazi order‹ (Moshe Tavor, Davar [fn 57]) (Government Press Office [GPO] D409-076) Eichmann in Jerusalem, July 1961: ›Eichmann continues to think in the categories of the Nazi order‹ (Moshe Tavor, Davar [fn 57]) (Government Press Office [GPO] D409-076)](https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/static/2023-2/Volovici_2-23_Abb5.jpg?language=en)

the categories of the Nazi order‹

(Moshe Tavor, Davar [fn 57]) (Government Press Office [GPO] D409-076)

The listeners heard in Eichmann not only the brutality of the Nazi genocidal apparatus, but also mere tediousness: ›The voice is deep, dim, monolithic [...]. Dozens of foreign reporters […] have come here specially to hear him […], and now they sit in the courtroom, the many reporters and the audience, impatiently, witnessing their decaying alertness and diminishing expectations, as they are yawning […]. All that he says, whatever he explains in long, convoluted, German sentences, is so utterly predictable, that it leaves no room for drama.‹58 Elsewhere Eichmann’s voice was described as haunting, ›the metal voice of a machine […], a voice that brings back echoes from the past‹.59 In Davar, a commentator noted that the defense lawyers were pursuing their efforts ›entirely in clumsy German, filled with subclauses and grammatical notes, a painful German crushed in this trial by obscene distortions‹.60 Shmuel Shnitser described how painful it was to listen to Eichmann’s ›sticky paste of words‹, produced by his ›sickly verbosity, grey dullness and painful dwelling in details of his [recorded] testimony‹. Shnitser believed that Eichmann’s psychological relation to the German language was of profound importance, providing him with the ability to make use of its ›capacity of composing lengthy sentences, of its impossible syntax, of its ceremonial vocabulary‹.61

Another writer remarked that those who did not speak German were at a disadvantage in deciphering the Eichmann riddle: ›Only those who are able to follow Eichmann’s convoluted sentences and those who can assess his desperate efforts to express himself adequately can move a step closer to understanding this question.‹62 Uri Avneri, a German-born Israeli journalist, appears to have been the first to describe Eichmann as ›banal‹ in his discussion of Eichmann, preceding Hannah Arendt’s famous use of the term. Avneri described Eichmann as ›a person of miserable appearance who lacks any special talents, is emotionally and spiritually impoverished, an inferior and banal person in every sense of the word.‹63 Moshe Tavor described Eichmann’s speech as having the traits of ›a half-educated person‹, who ›struggles to find the right term, stutters his way through the effort to find a proper definition, chatters needlessly before getting to the point, corrects himself all too often and dwells on insignificant details‹. After hearing the first part of the testimony, ›there is no doubt left that Eichmann remained a small bureaucrat who reached a high position due to his diligent efforts in the labor of death‹.64 In their observations of Eichmann’s behavior and language, Avneri and Tavor reached a similar conclusion that somewhat downplayed the centrality of ideology and hatred underlying Eichmann’s actions, emphasizing instead his mundane personality.

Eichmann’s German was thus a sensational element of the trial, as it appeared to capture aspects of the Nazi mindset more than the content of his speech did. At the same time, the idea of German as the Nazi language was challenged. Eichmann’s language conveyed confusion, submissiveness, and awkwardness. The anti-climactic dimension of the trial led many observers to pay growing attention to the bewildering ways in which Eichmann expressed himself. His language turned ideas of Nazi German into an unmediated experience for his listeners. But his use of German also generated new questions concerning the relationship between language and Nazi violence.

As noted above, Eichmann’s German was not the only type of German heard at the trial. Virtually all the main participants in the trial could speak German: the three judges were born and raised in Germany, Eichmann and his lawyers communicated exclusively in German, and the prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, was born in Habsburg Galicia in 1915 and was quite proficient in German. While the simultaneous interpretation rendered discussions with the defendant and his lawyers accessible to the wider audience, it did not have a facilitating function for the trial’s protagonists. Hannah Arendt (whose account of the trial will be discussed below) wrote in a letter to Karl Jaspers of ›the comedy of speaking Hebrew when everyone involved knows German and thinks in German‹.65 The different German accents heard throughout the trial, reflecting cultural, class, and geographic differences, contributed to its theatrical quality.66

The constant interpretation meant that the trial involved long pauses every step of the way. When the judges addressed the defendant, they had to wait for the interpreters to deliver their Hebrew words in German and vice versa, giving occasion to misunderstandings and mistranslations of the original. In a few cases in which the judges noted such mistakes, they intervened and corrected the translation. Sometimes the judges simply decided to save the hassle. In one instance in which Eichmann failed to answer Judge Moshe Landau’s question, Landau interjected, ›Perhaps I’ll explain it in German‹, repeating the question in German before reverting to Hebrew.67 In another instance, a judge noted Eichmann’s obscure terms, asking him to choose ›a clearer term in German‹ in his response.68 Prosecutor Hausner frequently resorted to German when interrogating Eichmann, in particular when raising follow-up questions or when he was seized with anger.69 In one case, he shouted: ›Haben Sie es gesagt? Ja oder nein?‹ (›Did you say it? Yes or no?‹).70 These linguistic shifts were rarely documented in the protocols.71

Upon completion of the prosecutor and defense attorney’s statements, the judges were given the opportunity to ask Eichmann questions on any matter they believed required further clarification. It was in this context that the façade of a linguistic barrier between the judges and the defendant was abandoned entirely. Judge Yitzhak Raveh began by saying in Hebrew: ›I will ask you a few questions in German‹, after which he turned to Eichmann and took off his glasses. What followed was a lengthy exchange between the two, held in German. Raveh’s decision may have been related not only to time constraints and impatience but also to the topic on which he decided to focus. His concluding questions pertained not to Eichmann’s deeds but to his moral convictions. Raveh invoked a comment Eichmann had made early in the interrogation, in which he said that his unalloyed commitment to the Nazi law was in line with Kant’s Categorical Imperative. Raveh asked Eichmann to explain his understanding of the Categorical Imperative, to which he responded that he understood it to mean that ›the principle of my will and the principle of my life must be such that it could at any time be raised to the principle of a universal law‹.72 It was on this matter that Raveh sought to dwell, not only exploring Eichmann’s understanding of Kant but also inquiring how it squared with the kind of actions in which he had engaged – organizing a mass killing of innocent human beings. Raveh’s didactic line of questioning left Eichmann little room to maneuver, until he admitted that in his capacity as a Nazi officer he did not follow Kant’s imperative.73 Raveh’s direct dialogue with Eichmann in their shared language led to one of the few instances in which Eichmann admitted a certain personal responsibility for his actions.

about his understanding of Kant’s Categorical Imperative

After this exchange, the linguistic barrier could no longer be rebuilt. Judge Benjamin Halevy began his series of questions by stating, ›I will also allow myself to deviate from the Hebrew order of the trial and ask the defendant in his own language‹, without adding any further justification.74 The presiding judge, Moshe Landau, asked his questions in Hebrew, then immediately translated them himself into German.75 During these few hours, the courtroom was a German-speaking room, where the Nazi perpetrator conversed with the Israeli judges – all Jewish immigrants and refugees from Germany – in their mother tongue. The key element in this Germanophone moment, however, lay in the fact that the judges mobilized their intimate knowledge of German to reveal obscure, inconsistent, or misleading statements made by Eichmann. They used German to exhibit Israel’s sovereign power over the German defendant.

6. Reading Hannah Arendt Hearing Eichmann’s German

No contemporary account of the trial has been as influential and as controversial as Hannah Arendt’s book Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil. As Bettina Stangneth posited, it is impossible to write about Eichmann without being in dialogue with Arendt.76 Published by The New Yorker in 1963, then revised and published in book form, Arendt’s report involved an effort to interpret the historical and psychological impulses which allowed Eichmann to engage in the organization of mass murder. According to Arendt, Eichmann represented a specific form of totalitarian thinking, predicated on modern political ideologies and codes of professional conduct. For Arendt, the key quandary with any attempt to assess Eichmann as an architect of mass murder lay in the troubling fact that he was a normal man, not a hate-filled psychopath: ›The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal.‹77 The modern qualities informing Eichmann’s self-perception – as a cog in a system, a bureaucrat carrying out decisions passed down to him – buttressed his inability to think independently, to weigh his actions according to criteria exterior to those that dictated his work, or to see things through other people’s eyes. Arendt’s argument has stirred heated, at times vitriolic, debates, and in recent decades drawn renewed attention in a number of different academic disciplines. Of relevance for our discussion is Arendt’s consideration of language in the trial and as used by Eichmann.

Arendt was writing from the superior position of a native speaker, and ascribed crucial importance to language as an analytical tool. As Seyla Benhabib noted, Arendt was able to sense the mixture of ideological and psychological traits in Eichmann ›because she was so well attuned to Eichmann’s use of language‹.78 For Arendt, Eichmann’s language was a reflection of his thought mechanisms, i.e., his thoughtlessness.79 Commenting on the transcripts of his interrogation, Arendt observed that ›[…] the horrible can be not only ludicrous but outright funny. Some of the comedy cannot be conveyed in English, because it lies in Eichmann’s heroic fight with the German language, which invariably defeats him.‹80 In Arendt’s view, the German language in its proper form is a language of eloquence and precision and a solid, powerful entity that can expose the weakness of those who try vainly to show command of it despite their linguistic ineptitude.

To understand what constituted this ineptitude, it may be helpful to invoke Arendt’s comment on an exchange between Judge Landau and Eichmann. The latter was unable to clarify an expression he was using and stated: ›Officialese [Amtssprache] is my only language.‹ Arendt then explained: ›Officialese became his language because he was genuinely incapable of uttering a single sentence that was not a cliché.‹ What Arendt recognized in Eichmann’s language was, for her, clear proof of her thesis – ›his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else‹.81 She described Eichmann as a person characterized by an ›incapacity for ordinary speech‹.82 Her linguistic analysis of Eichmann presented him ultimately as mentally unfit: ›No communication was possible with him, not because he lied but because he was surrounded by the most reliable of all safeguards against the words and the presence of others, and hence against reality as such.‹83

Arendt’s analysis of Eichmann was heavily informed by a perception that granted language – and specifically the German language – significant power.84 Indeed, her approach to German consisted of more than a sentimental relationship to one’s mother tongue. It involved a belief in the distinctive qualities of German. For example, she held that German was particularly well suited to making philosophical statements (though English and French were more suitable for political thought), and she was in this sense a custodian of a specific tradition of thinking about the inherent qualities of German.85 In his discussion of Arendt’s relationship with the German language, Stephan Braese argued that Arendt maintained in her work an ongoing belief in the resilience and almost magical force of the German language, a force which remained intact even after the language had been instrumentalized by the Third Reich.86 It was in the context of this reverent approach to German that Arendt tried to decipher Eichmann.

In her study of the Eichmann trial, Shoshana Felman took this approach further, seeing Eichmann’s language as a ›quasi-parodic German, a German limited to an anachronistic use of Nazi bureaucratic jargon (noticeable during the trial to every native German speaker as the farcical survival of a sort of robot-language), [which] takes the place of mens rea‹ [i.e., the intent behind the crime]. Felman’s conclusion, following Arendt’s path, was that ›Eichmann does not speak the borrowed (Nazi) language: he is rather spoken by it, spoken for by its clichés, whose criminality he does not come to realize‹.87 Such an interpretation brings full circle the idea that the German language had a possessive power over its speakers. Eichmann’s dependence on Nazi bureaucratic language was but one manifestation of the power of the German language. This view, however, according to which Eichmann was a virtually passive, technocratic mouthpiece of Nazi language, does not stand up to the historical research conducted in recent years, above all by Bettina Stangneth. As Stangneth has demonstrated, drawing on a close analysis of the available written material and recordings of Eichmann from before and during the trial, Eichmann was in fact perfectly able to express himself and describe his actions in ›non-officialese‹ manner.88 His extensive reliance on ›officialese‹ was a calculated choice designed to convey an image of himself as nothing more than a diligent bureaucrat, camouflaging in this way his ideological and personal motivations in executing the Final Solution. As Tuija Parvikko has argued, the fact that Eichmann had far more agency over his language than Arendt (and subsequent readers) tended to believe does not invalidate her essential argument about the form of modern evil perpetrated by the Nazi regime and embodied in Eichmann’s actions.89 Yet precisely because Arendt laid emphasis on Eichmann’s language as a key to understanding his actions and his self-rationalization, it is important to historicize her view of language. Indeed, Arendt’s reverence for German led her to see it as a force that possessed Eichmann, as a solid entity against which Eichmann’s inner self could be detected. She did not fully consider the rhetorical functions of the language’s malleability during the trial.

Arendt’s careful attention to Eichmann’s language can also be read against other languages she encountered in Jerusalem. In her correspondence with Karl Jaspers, Arendt gave vent to certain stereotypes of Eastern European Jews and other ›Orientals‹: ›[…] on top, the judges, the best of German Jewry. Below them, the prosecuting attorneys, Galicians, but still Europeans. Everything is organized by a police force that gives me the creeps, speaks only Hebrew, and looks Arabic. Some downright brutal types among them. They would obey any order. And outside the doors, the Oriental mob, as if one were in Istanbul or some other half-Asiatic country.‹ She praised the three judges’ eloquent German, and contrasted it with the German spoken by Hausner, ›a typical Galician Jew, very unsympathetic, […] constantly making mistakes. Probably one of those people who don’t know any language.‹90

As the discussion above shows, Arendt’s view of the trial and of Eichmann was informed by her encounter with the different modes of German used around her in Jerusalem. The fact that Arendt presented Eichmann as an inferior native speaker of German was significant. But no less important was the broader linguistic setting of the trial, which confronted Arendt with non-native German speakers, unfolding a history of tensions over linguistic hierarchies in German and Jewish cultures.

Stephan Braese describes Arendt as representing a key facet of a Jewish linguistic culture (Sprachkultur) that was deeply attached to the German language and to its role in modern Jewish culture.91 In this article I have pointed to an additional Jewish Sprachkultur, one that was nourished not only by German speakers, but also by those who acquired German as a second or third language through immigration, studies, or their knowledge of Yiddish. This broader Sprachkultur also encompassed those whose relationship with German evolved as readers or listeners and not as speakers or writers of the language. Within this Jewish Sprachkultur, the relationship to German was more functional, and often more ambivalent. Analyses of Arendt and Eichmann should take into account the fact that the former’s reading of the latter took place within a historically fraught setting that brought together several German, Jewish, and German-Jewish ways of speaking and of thinking about German.

The trial proved to be a unique encounter between different meanings of German. Ideas of German as the language of Nazi brutality received their performative validation, but in so doing they opened up questions about the driving motivations, character and beliefs of Nazi functionaries. German also appeared in its obsolete function as a key language of interaction between different factions of Ashkenazi Jewry before the Holocaust. Additionally, Nazi German was consigned to a defensive, weak position, whereas proper, educated German was a vehicle through which the Israeli juridical court exercised its power. It was therefore not merely a symbolic matter that the trial was profoundly multilingual and heavily Germanophone; this fact added a crucial sensory dimension to the listeners’ encounter and reencounter with the German and Jewish pasts. The Eichmann trial granted German a degree of audibility unprecedented in the short history of the State of Israel. It prompted a gradual, often reluctant, return to Germanophone features of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. In this sense, it helped demystify the German language.

The anti-German boycott waned in the 1960s, and the historical burden of German as a Nazi language stirred fewer and fewer controversies. The heated debates over whether German should be allowed into the Israeli public sphere weakened considerably. Israelis of German descent felt less pressure to avoid using the German language.92 The formation of a commemorative culture of the Holocaust involved a relaxation of the idea of German as a ›dangerous language‹. Being rendered more palpable, more audible, it lost some of its threatening qualities. When Eichmann, Landau, Hausner, Grynszpan and others spoke in German, the echoes of their German were manifold and diverse. This attests to the splintered historical memory embedded in the German language – a memory composed of different historical currents of Jewish diasporic experience, and marked by geographic, national, ideological, and class divisions. Indeed, the political and emotional valence of postwar debates on German and the Holocaust derived to a large degree from the tension between recent and more distant legacies of the German language.

Notes:

1 Paul Celan, Collected Prose, trans. Rosmarie Waldrop, Riverdale-on-Hudson 1986, p. 34.

2 George Steiner, Language and Silence. Essays on Language, Literature, and the Inhuman, New York 1967, p. 108. See discussion in: Marc Volovici, The Contamination of Language: George Steiner and the Postwar Fate of German and Jewish Cultures, in: Arndt Engelhardt/Susanne Zepp (eds), Sprache, Erkenntnis und Bedeutung – Deutsch in der jüdischen Wissenskultur, Leipzig 2015, pp. 265-280. See also Nicolas Bergʼs and Stephan Braeseʼs article in this issue.

3 On Eichmann and his role in the Final Solution, see: Bettina Stangneth, Eichmann Before Jerusalem. The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer, trans. Ruth Martin, London 2016; Hans Safrian, Eichmann’s Men, trans. Ute Stargardt, Cambridge 2010; David Cesarani, Becoming Eichmann. Rethinking the Life, Crimes, and Trial of a »Desk Murderer«, Cambridge 2006.

4 Tom Segev, The Seventh Million. The Israelis and the Holocaust, trans. Haim Watzman, New York 1993, pp. 35-64; Hanna Yablonka, The State of Israel vs. Adolf Eichmann, trans. Ora Cummings/David Herman, New York 2004; Deborah E. Lipstadt, The Eichmann Trial, New York 2011; Rebecca Wittmann (ed.), The Eichmann Trial Reconsidered, Toronto 2011; David Cesarani (ed.), After Eichmann. Collective Memory and the Holocaust since 1961, New York 2005.

5 Annette Wieviorka, The Era of the Witness, trans. Jared Stark, Ithaca 2006; Carolyn J. Dean, The Moral Witness. Trials and Testimony after Genocide, Ithaca 2019; Lawrence Douglas, The Memory of Judgment. Making Law and History in the Trials of the Holocaust, New Haven 2005.

6 Shoshana Felman, The Juridical Unconscious. Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge 2002; Valerie Hartouni, Visualizing Atrocity. Arendt, Evil, and the Optics of Thoughtlessness, New York 2012.

7 Ha-mishpat shel Adolf Eichmann: reshumot mishpat ha-yoets ha-mishpati shel memshelet yisrael neged Adolf Eichmann be’vet ha-mishpat ha-mehozi u’be’vet ha-mishpat he-elyon beshevto ke’vet mishpat le’irurim plili’im bi’yerushalayim [The Trial of Adolf Eichmann: Record of Proceedings in the District Court of Jerusalem and the Supreme Court], Jerusalem 2003, p. 98. All translations are mine unless stated otherwise.

8 My recent book tells the Jewish history of the German language and of its place in the formation of Jewish nationalism: Marc Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem. The Language Politics of Jewish Nationalism, Stanford 2020.

9 Jeffrey A. Grossman, The Discourse on Yiddish in Germany. From the Enlightenment to the Second Empire, Rochester 2000; Sander L. Gilman, Jewish Self-Hatred. Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews, Baltimore 1986. See also Miriam Chorley-Schulzʼs article in this issue.

10 Hillel ben Shachar [pseud.], Hasifrut ha’ivrit be’eretz yisrael [Hebrew Literature in Eretz Israel], in: Ha-Magid, 28 November 1895.

11 Dietz Bering, Jews and the German Language: The Concept of Kulturnation and Anti-Semitic Propaganda, in: Norbert Finzsch/Dietmar Schirmer (eds), Identity and Intolerance. Nationalism, Racism, and Xenophobia in Germany and the United States, Cambridge 1998, pp. 251-291; Jacob Toury, Die Sprache als Problem der jüdischen Einordnung im deutschen Kulturraum, in: Jahrbuch des Instituts für deutsche Geschichte 4 (1982), pp. 75-96; Shulamit Volkov, Sprache als Ort der Auseinandersetzung mit Juden und Judentum in Deutschland, 1780–1933, in: Wilfried Barner/Christoph König (eds), Jüdische Intellektuelle und die Philologien in Deutschland 1871–1933, Göttingen 2001, pp. 223-238.

12 Richard Wagner, Judaism in Music, in: Charles Osborne (ed.), Richard Wagner: Stories and Essays, London 1973, p. 27.

13 Sh. Y. Abramovitsh, A sguleh tsu di yudishe tsores [A remedy for Jewish troubles], in: Der nitslekher kalendar far di rusishe yidn 1884, p. 71.

14 On the Zionist congress and its language politics, see: Marc Volovici, Who Owns the German Language? Zionism from Hochdeutsch to Kongressdeutsch, in: Darcy Buerkle/Skye Doney (eds), Contemporary Europe in the Historical Imagination. George L. Mosse and Contemporary Europe, Madison 2023, pp. 216-233. On the language politics in Palestine, see: Liora R. Halperin, Babel in Zion. Jews, Nationalism, and Language Diversity in Palestine, 1920–1948, New Haven 2014.

15 Michael Volkmann, Neuorientierung in Palästina, 1933 bis 1948, Cologne 1994, pp. 86-98; Miriam Geter, Ha-aliyah me’germania ba’shanim 1933–1939: Klita hevratit-kalkalit mul klita hevratit-tarbutit, [The German immigration of 1933–1939: Socio-economic integration versus socio-cultural integration], in: Katedra 12 (1979), pp. 125-147, especially pp. 139-146; Yoav Gelber, Al ha-kavenet: ha-itonut ha-germanit [Targeting the German press], in: Kesher 4 (November 1998), pp. 101-105; Segev, The Seventh Million (fn 4), pp. 35-64.

16 Eliezer Yaffe, Im tnu’at ha-ezra la’yehudim mi’germania [Amid the aid work to German Jewry], in: Ha-poel ha-tsa’ir, 5 May 1933.

17 Menahem G. Geln, Be’einayim yerukot [Green eyes], in: Do’ar Hayom, 15 February 1935. Emphasis in original.

18 TS. [Dov Sadan], Derekh agav [A propos], in: Davar, 25 January 1940.

19 See discussion in: Raquel Werdyger-Stepak, Kehilat ha-sofrim ha-ivri’im be’erets yisrael u’tguvata le’nokhah ha-shoa (1939–1945) [Hebrew Writers in Eretz Israel and their Responses to the Holocaust, 1939–1945], PhD Diss., Tel Aviv University 2011, pp. 440-442.

20 Moshe Ungerfeld, Veʼitkha ha-sliha [I beg your pardon], in: Ha-Tsofe, 8 December 1944.

21 Y. Tsdadi, Kmatim [Wrinkles], in: Ha-Tsofe, 5 October 1945.

22 D.B.M., Morav shel James Middleton [James Middleton’s teachers], in: Al Ha-Mishmar, 24 December 1944.

23 Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem (fn 8), pp. 200-228.

24 Na’ama Sheffi, Cultural Manipulation: Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss in Israel in the 1950s, in: Journal of Contemporary History 34 (1999), pp. 619-639. See also: Na’ama Sheffi, The Ring of Myths. The Israelis, Wagner and the Nazis, Eastbourne 2013, pp. 47-64.

25 Sharett hazar le’yisrael [Sharett returned to Israel], in: Davar, 12 September 1952.

26 Sh. H. Bergmann, Ha-germanit [The German language], in: Davar, 28 September 1959.

27 Nathan A[lterman], Ha-omnam ko gdola ha-herpa? [Is it really a disgrace?], in: Davar, 9 October 1959.

28 Amit Pinchevski/Tamar Liebes/Ora Herman, Eichmann on the Air: Radio and the Making of an Historic Trial, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 27 (2007), pp. 1-25.

29 In the description of the trial, the article makes use of some excerpts from: Volovici, German as a Jewish Problem (fn 8), pp. 218-225.

30 Tirgumim, pirsumim ve’hafatsot [Translations, publications, dissemination], Israel State Archives, 3119/8-A.

31 Ruth Morris, Justice in Jerusalem: Interpreting in Israeli Legal Proceedings, in: Meta 43 (1998), pp. 1-10.

32 The decision to call it a ›Bureau‹ rather than a ›special unit‹ had to do with the connotation of the latter term in Nazi terminology (as in Sonderabteilung). Notebook, 25 May 1960, ETH Zürich, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, NL Avner W Less / 109.

33 Cesarani, Becoming Eichmann (fn 3), p. 241. On the work of Bureau 06, see: Sharon Geva, Be’tsel ha-tvi’a: mishteret Israel (lishka 06) be’farashat mishpat Eichmann [In the shadow of the prosecution: Israel Police (Bureau 06) in the Eichmann trial], in: Nomi Levenkron/Tamar Kricheli Katz (eds), Mishpat u’mishtara [Law and Police], Tel Aviv 2021, pp. 83-106.

34 Shalom Rosenfeld, Abgase – Zwangssterilisierung, in: Maariv, 11 April 1961.

35 Eichmann Trial Administration: Glossary: German – French – English, 23 March 1961, ETH Zürich, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, NL Avner W Less / 51.

36 Victor Klemperer, LTI. Notizbuch eines Philologen, Berlin 1947. See Nicolas Bergʼs contribution to this issue.

37 Steiner, Language and Silence (fn 2), pp. 95-110.

38 Two recent works tackling these questions are: Moritz Föllmer, Culture in the Third Reich, trans. Jeremy Noakes and Lesley Sharpe, Oxford 2020; Bernd Witte, Moses und Homer. Griechen, Juden, Deutsche: Eine andere Geschichte der deutschen Kultur, Berlin 2018.

39 Ha-mishpat shel Adolf Eichmann (fn 7), pp. 121, 1474.

40 Ibid., pp. 1473-1474.

41 Ibid., pp. 1339-1340.

42 Ibid., p. 1343.

43 Ibid., pp. 1364-1365.

44 Ibid., p. 1451.

45 Ibid., p. 1034. On this term, see: Wolfgang Sofsky, The Order of Terror. The Concentration Camp, trans. William Templer, Princeton 1997, pp. 199-205.

46 Ha-mishpat shel Adolf Eichmann (fn 7), pp. 1036, 1041-1043, 1092.

47 These include memoirs published in the late 1940s and 1950s by Auschwitz survivors such as Primo Levi, Hermann Langbein, and Olga Lengyel, and historian Philip Friedman’s book Martyrs and Fighters. The Epic of the Warsaw Ghetto, New York 1954.

48 Hannah Pollin-Galay, »A Rubric of Pain Words«: Mapping Atrocity with Holocaust Yiddish Glossaries, in: Jewish Quarterly Review 110 (2020), pp. 161-193, and her article in this issue. See also Gali Drucker Bar-Am’s analysis of the Yiddish press and the Eichmann trial: Gali Drucker Bar-Am, The Holy Tongue and the Tongue of the Martyrs: The Eichmann Trial as Reflected in Letste Nayes, in: Dapim. Studies on the Holocaust 28 (2014), pp. 17-37.

49 Yehoshua Bitsor, Matayim mila le-daka – be 4 safot [200 words per minute – in four languages], Maariv, 31 March 1961; Macabee Dean, … Two or Three Words behind the Speaker, in: Jerusalem Post, 26 April 1961.

50 Notebook, 29 May 1960, ETH Zürich, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, NL Avner W Less / 109. See: Avner Werner Less, Lüge! Alles Lüge! Aufzeichnungen des Eichmann-Verhörers. Rekonstruiert von Bettina Stangneth, Zurich 2012, p. 113. In an essay published in 1983, Less depicted his first impression differently and somewhat more harshly, echoing to some degree Hannah Arendt’s view of Eichmann’s German, which will be discussed below. Less writes: ›His German was hideous. At first I had a very difficult time understanding him at all – the jargon of the Nazi bureaucrat pronounced in a mixture of Berlin and Austrian accents and further garbled by his liking for endlessly complicated sentences in which he himself would occasionally get lost.‹ Avner W. Less, Introduction, in: Jochen von Lang/Claus Sibyll (eds), Eichmann Interrogated. Transcripts from the Archives of the Israeli Police, New York 1999, xx-xxi.

51 Shalom Rosenfeld, Masa gey ha’harega ba’mishpat bi’yerushalaim [The burden of the killing grounds presented in the Jerusalem trial], in: Maariv, 17 April 1961.

52 Yedioth Ahronot, 12 April 1961. See also: Moshe Tavor, Yoman ha-mishpat [Trial diary], in: Davar, 12 April 1961; Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Herut, 12 April 1961.

53 Yaacov Even-Hen, Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Ha-Tsofe, 12 April 1961.

54 Shabtai Teveth, Eichmann mul ha-ashma [Eichmann facing his guilt], in: Haaretz, 12 April 1961.

55 Moshe Tavor, Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Davar, 21 April 1961.

56 Moshe Tavor, Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Davar, 23 April 1961.

57 Moshe Tavor, Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Davar, 21 June 1961.

58 Shmuel Shnitser, Ha-emet, kol ha-emet, ve’rak ha-emet [The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth], in: Maariv, 21 June 1961. Italics in original.

59 Menahem Shmuel, Kol ha-mekhona ba’mishpat [The voice of the machine in the trial], in: Ha-Boker, 21 April 1961.

60 M. Gross-Zimmermann, Aharei hidush ha-mishpat [As the trial resumes], in: Davar, 23 June 1961.

61 Shmuel Shnitser, Isa dvika shel milim . . . [Sticky paste of words], in: Maariv, 22 June 1961.

62 Moshe Tavor, Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Davar, 22 June 1961.

63 Uri Avneri, Ha-robot ha-rats’hani [The lethal robot], in: Etgar, 27 July 1961.

64 Moshe Tavor, Yoman ha-mishpat, in: Davar, 21 April 1961.

65 Hannah Arendt/Karl Jaspers, Correspondence, 1926–1969, eds Lotte Kohler/Hans Saner, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber, New York 1992, p. 434.

66 Omer Bartov, The »Jew« in Cinema. From The Golem to Don’t Touch my Holocaust, Bloomington 2005, pp. 78-92.

67 Ha-mishpat shel Adolf Eichmann (fn 7), p. 1194.

68 Ibid., p. 1298.

69 Ibid., p. 1370.

70 Ibid., pp. 1390, 1391, 1398, 1405, 1417.

71 Ibid., pp. 1374, 1413, 1415.

72 ›Da verstand ich darunter, dass das Prinzip meines Wollens und das Prinzip meines Lebens so sein muss, dass es jede Zeit zu[m] Prinzip einer allgemeinen Gesetzgebung erhoben werden könnte.‹

73 Ha-mishpat shel Adolf Eichmann (fn 7), p. 1518.

74 Session 106, 40:30, URL: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUsrodSkb8k>.

75 Ha-mishpat shel Adolf Eichmann (fn 7), p. 1535.

76 Stangneth, Eichmann Before Jerusalem (fn 3), xxxii. See also: Tuija Parvikko, Arendt, Eichmann and the Politics of the Past, Helsinki 2011; Peter Burdon, Hannah Arendt. Legal Theory and the Eichmann Trial, New York 2018; Steven E. Aschheim (ed.), Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem, Berkeley 2001.

77 Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil [1963], New York 2006, p. 276.

78 Seyla Benhabib, Exile, Statelessness, and Migration. Playing Chess with History from Hannah Arendt to Isaiah Berlin, Princeton 2018, p. 69.

79 Daniel Conway, Banality, Again, in: Richard J. Golsan/Sarah Misemer (eds), The Trial that Never Ends. Hannah Arendt’s ›Eichmann in Jerusalem‹ in Retrospect, Toronto 2017, pp. 67-91, here p. 80.

80 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem (fn 77), p. 48.

81 Ibid., p. 49.

82 Ibid., p. 86.

83 Ibid., p. 49.

84 Arendt succinctly expressed her attachment to language and specifically to German in a famous 1964 interview. When asked what remained of the pre-war world after the years of devastation, she answered: ›What remains? The language remains. […] The German language is the essential thing that has remained and that I have always consciously preserved.‹ Hannah Arendt, »What Remains? The Language Remains«: A Conversation with Günter Gaus, in: Arendt, Essays in Understanding, 1930–1954. Formation, Exile, and Totalitarianism, ed. by Jerome Kohn, New York 2005, pp. 1-23, here pp. 12-13. In German: <https://www.rbb-online.de/zurperson/interview_archiv/arendt_hannah.html> (transcript), <https://www.zdf.de/dokumentation/zur-person/hannah-arendt-zeitgeschichte-archiv-zur-person-gaus-100.html> (video).

85 On Arendt’s relationship to German and translation, see: Marie Louise Knott, Unlearning with Hannah Arendt, trans. David Dollenmayer, Berlin 2011, pp. 31-56.

86 Stephan Braese, Hannah Arendt und die deutsche Sprache, in: Ulrich Baer/Amir Eshel (eds), Hannah Arendt zwischen den Disziplinen, Göttingen 2014, pp. 29-43.

87 Felman, The Juridical Unconscious (fn 6), pp. 212-213. Italics in original. See also: Dagmar Barnouw, Speaking about Modernity: Arendt’s Construct of the Political, in: New German Critique 50 (1990), pp. 21-39; Jakob Norberg, The Political Theory of the Cliché: Hannah Arendt Reading Adolf Eichmann, in: Cultural Critique 76 (2010), pp. 74-97.

88 Stangneth, Eichmann Before Jerusalem (fn 3), p. 268.

89 Parvikko, Arendt (fn 76), xix-xxi.

90 Arendt/Jaspers, Correspondence (fn 65), p. 434.

91 Stephan Braese, Eine europäische Sprache. Deutsche Sprachkultur von Juden 1760–1930, Göttingen 2010.

92 On the language of German-speaking immigrants and their descendants in Israel, see Anne Betten, Sprachbiographien der 2. Generation deutschsprachiger Emigranten in Israel. Zur Auswirkung individueller Erfahrungen und Emotionen auf die Sprachkompetenz, in: Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 40 (2010) issue 4, pp. 29-57; Anne Betten, Zusammenhänge von Sprachkompetenz, Spracheinstellung und kultureller Identität – am Beispiel der 2. Generation deutschsprachiger Migranten in Israel, in: Eva Maria Thüne/Anne Betten (eds), Sprache und Migration. Linguistische Fallstudien, Rome 2011, pp. 53-87.