After World War II, many historians in the German-speaking world thought of the relationship between anthropology and history as being largely synonymous with that of ›everyday life‹ (Alltag) and ›structure‹. As Jürgen Kocka (b. 1941) wrote in a retrospective statement to the Zurich historian Rudolf Braun (1930–2012), one of the few prominent figures of ›ethnographic‹ social history especially in the 1970s and 1980s: ›For while we, a younger generation of social historians, have turned to the large structures and processes that conditioned, encompassed and shaped people’s lives, Braun has always supported us, but he insisted – in an untimely but fruitful way – on not missing the people’s »inside«: the experiences and habits, the hopes and disappointments, the everyday life and mentalities of common people in the age of industrialization.‹1

To be sure, anthropology and history have been in conversations with each other far beyond the works of Braun, for example in Thomas Nipperdey’s cultural history, in Alltagsgeschichte or historical anthropology; yet, the role of anthropology has usually been to inject more ›everyday life‹, ›mentality‹ and ›experience‹ into the somewhat dry structural history.

More recently, however, the situation has changed. Inspired by scholarship from media studies, the history of science, global and environmental history, as well as the Anthropocene discourse, the dialogue between anthropologists and historians has gained new momentum, particularly in the anglophone world. Much of this scholarship revolves around ›infrastructures‹. Yet, instead of being interested in infrastructures as mere ›structures‹ and technical set-ups, scholars at the interface of anthropology and history explore their everyday life, their social (dys)functionality, and the legal and political regimes that have historically emerged with them. This scholarship is also fueled by an increasing public concern about the maintenance of the dilapidated infrastructures of ›high modernity‹.2

In the following conversation, historian Nils Güttler and anthropologist Lena Kaufmann discuss the recent shifts with two go-betweens in history and anthropology: historian Debjani Bhattacharyya and anthropologist Brian Larkin. Bhattacharyya’s research on ecology and law in the Bengal Delta and Larkin’s studies of media infrastructures in Nigeria demonstrate how a combined historical and anthropological lens is essential for understanding complex, multifaceted social and environmental phenomena, particularly in (post)colonial settings. This dialogue is an attempt to reflect on how combined methodologies might offer new insights into the pressing issues of our time such as colonial pasts, environmental questions and climate change, resource extraction and urbanization, infrastructures and global flows of technology and knowledge. What is the value of integrating historical and anthropological perspectives? Where do the boundaries between the two blur, and in what ways can such transgressions be not only beneficial but necessary?

- Debjani Bhattacharyya (University of Zurich) is a professor for the history of the Anthropocene. Prior to that, she taught environmental history at Drexel University, heavily influenced by the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS). She authored Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta. The Making of Calcutta, Cambridge 2018.

- Brian Larkin (Barnard College, Columbia University) is a professor of anthropology as well as Codirector of the Society of Fellows/Heyman Center for the Humanities at Columbia University. He is the author of Signal and Noise. Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria, Durham 2008, and the co-editor of Media Worlds. Anthropology on New Terrain, Berkeley 2002.

The conversation took place via Zoom in April 2023. Jenny Furter provided the transcript. Nils Güttler and Lena Kaufmann conceptualised and asked the questions and edited the text. Nils Güttler is an assistant professor for the History of Science at the University of Vienna. His research focuses on the history of environmental sciences and scientific activism, e.g. in his monograph Nach der Natur. Umwelt und Geschichte am Frankfurter Flughafen, Göttingen 2023. Lena Kaufmann is an SNSF Ambizione Fellow at the University of Fribourg. Trained as an anthropologist and sinologist, her research interests include China, digital infrastructures, technologies, agriculture and migration. She is the author of Rural-Urban Migration and Agro-Technological Change in Post-Reform China, Amsterdam 2021.

Lena Kaufmann/Nils Güttler: We have asked both of you to bring along an object that emphasises the mutual encounters of history and anthropology in your work. Now, of course, we are curious.

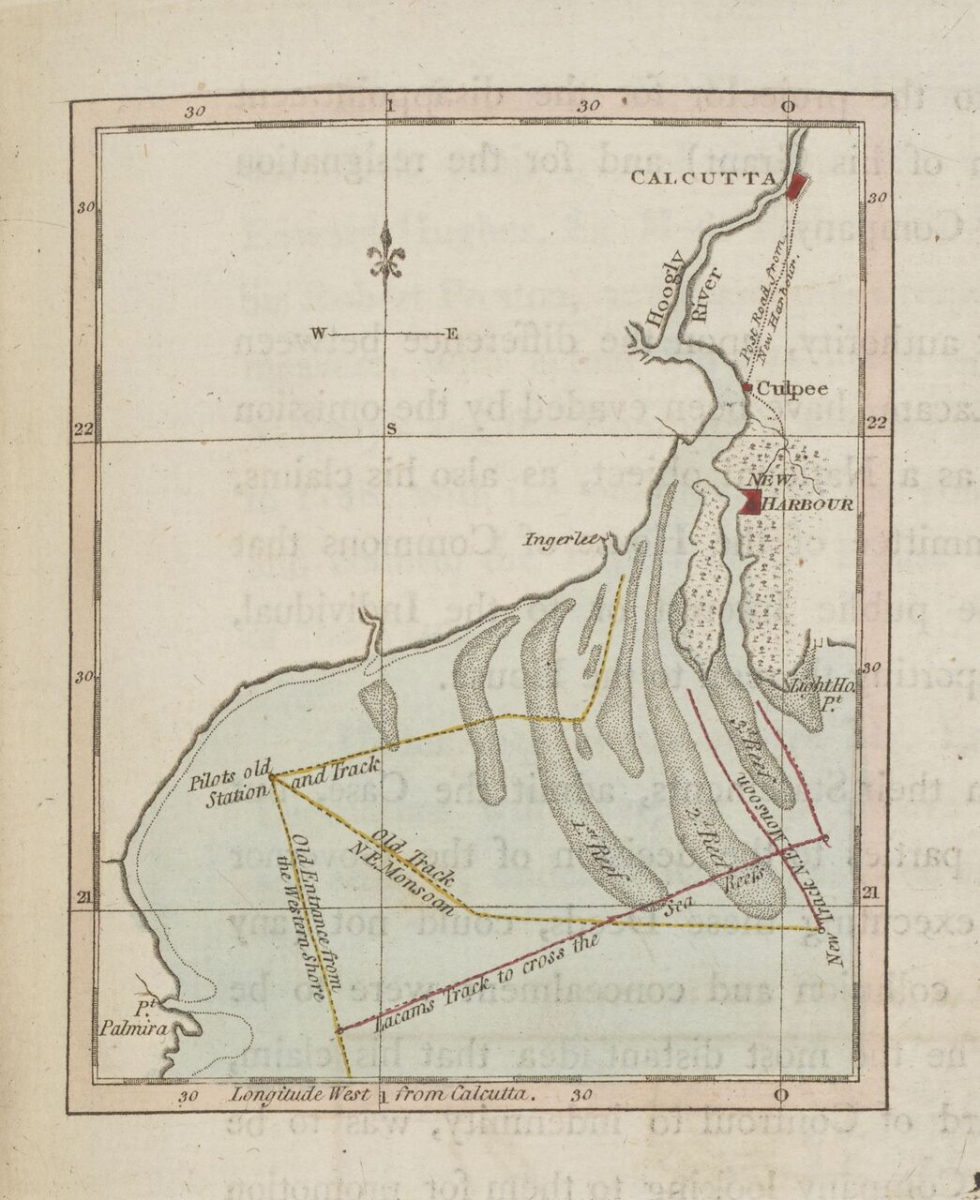

Debjani Bhattacharyya: My object is a land grant from 1773, archived in the British Library. It is written in Medieval Bengali, a very Persianate Bengali. We can call it an object or call it an archival material. It is folio and the land grant is bi-lingual. It begins in English giving extensive marking of the so-called land that would be granted. The section that interests me is the bottom, which is in Bengali script and summarizes the English land grant, although added as a translation. This was a land grant given to a British speculator, who was trying to build a harbour in a marshy delta space of sediment and water admixture. It is interesting to look at this land grant as a kind of infrastructure, by which I mean a tool to organise administratively a space of water or a space of mud and legally separate land from water. These spaces could not be represented with the available kinds of documentary regimes, thus the land grant acts more like an infrastructural presence here. What must be noted too is that I have access to this document as a historian precisely because the harbour never became operationalised and the project failed, leaving behind a legal trail of papers. It became a huge property debate for 30 years, from 1770 to 1803 turning on whether this was a piece of land or water. The case began in the Mayor’s Court of Calcutta and ended up traveling to the Justices of the Peace, an administrative court to handle civil suits in London. On the other side of the folio with the land grant the following map is appended to depict the space of water where the so-called harbour would be built.

(From the British Library Collection:

Benjamin Lacam Papers, IOR/H/396, p. 321)

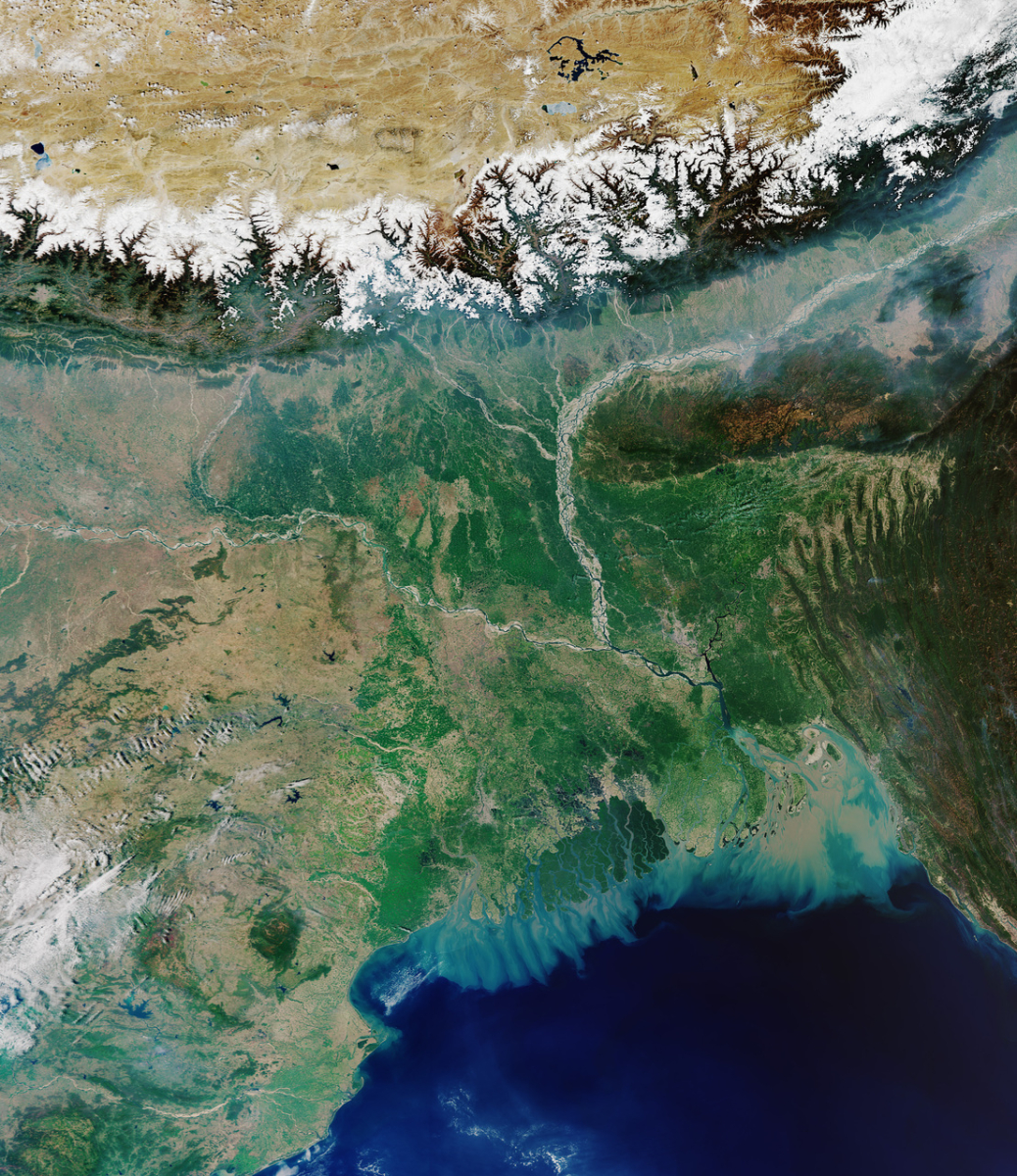

For me, the object raised a set of questions: What infrastructure do we need to represent the kind of spaces that we encounter in the delta region of the Bay of Bengal or in the Indian Ocean littorals? One of the questions the lawyers raised in 1770 was whether geography could be valid evidence within the legal context? How do we understand this failed harbour project? And, drawing on Brian’s work: How do we look at this failure as a way to understand state power? It would be easy to look at this as a failure of the expansion of the East India Company in the delta. But what we know from the seventeenth century on, the East India Company went on to occupy all of these spaces, although land grants or maps cannot necessarily represent the space in this region. Indeed, all our representative tools from maps to GIS continue to fail to accurately represent the delta since in this region, where land and silt soak into the rivers and oceans, challenging any ideas that coastlines are fixed.

This image was captured on 31 March 2020

by the European Space Agency (ESA).

(Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2020,

Wikimedia Commons, Ganges Delta ESA22274217, ESA,

CC BY-SA IGO 3.0)

Thinking through the anthropological literature on law as an infrastructure was my way of writing the environmental history of these ecotonal spaces of brackish water, where land moves and water stands still.3 If histories of property are about fixed lands, anthropology opened up a way to think about these marshes as spaces sedimented with stories, knowledges that went beyond the paper regimes of property and imperial cartography. Today, as vast parts of the delta are threatened by climate change, the forgotten history of living with land and water in these soaking ecologies becomes even more important. There is an old saying in Bengal that during monsoon farmers go fishing in their fields. This saying hints at the fact that farmers knew not only how to survive in floods, but also use brackish waters in these soaking ecologies.

Brian Larkin: My object is a photograph, showing a generator in a market in Nigeria. I am interested in electricity, the generator and the worlds the generator brings into being. This is part of my long-term interest in the history of colonial infrastructures and media in that region.4 What I find interesting about infrastructures is that they are processual. Objects are often conceptualized in their singularity. Infrastructures, by contrast, are systems that grow over space by encountering and interacting with other systems. They are about routinization and extension, interaction and articulation, breakdown and maintenance. They are inherently historical in that they unfold over time. The generator is a technological object in itself, but one that comes into use when the electricity system fails. Its operation is tied to the system as a whole. I am also interested in the way the generator is both a material device and a representational object. As a device it provides electricity. But as a representational object it congeals within itself a nationalist promise of development through electrical provision and the failure of that promise. It is meta-reflexive, a key object through which Nigerians critique the state, petrol cabals, and the political economy of Nigeria today. As material objects, generators distribute electricity, and as representational ones they organize politics – both at the same time. Finally, I am also interested in the ambient worlds that generators bring into being. They ingest things: petrol. And they expel things: electricity, but also heat, sound, and fumes. As they do so they create a technologized physical environment that Nigerians live in. We all live in worlds where our ambient experience of life – how a world smells or sounds, how light or dark it is, how soft or hard – is constituted by technologies. And in Nigeria, as in many other countries, that physical environment has a history and a politics tied to the colonial and nationalist politics of infrastructures, to developmentalist states and structural adjustment policies.

In my research I tend to start in the present, with a thing in the world, and then look backward: What work does this object do? How is it operating? How did it get here? Why is it here? I tack between the present and the past and do not make a major distinction between anthropology and history as discrete disciplines. I am more guided by asking a series of questions that interest me about an object, its role in everyday life, and the other domains it provokes and to which it is attached.

When the power grid breaks down and generators kick into life, what is brought into being is the failed promise of infrastructural development. This indexes breakdown as a sense of loss and a source of political critique. But breakdown is also a mode of possibility; if one system breaks down, another is provoked into existence. The generator began in Nigeria as a supplement to increased load shedding. But over the last two decades, since the entry of cheap Chinese generators into the Nigerian market and the worsening of blackouts, the supplement and the main network have grown together and are better seen as a single, integrated system. This idea that breakdown is not simply foreclosure but generative is an idea I took from Michel Serres’ Le parasite.5 For him, the parasite is something that interrupts an existing system but then, by intervening into it, détourns it, diverting it to new uses, ultimately bringing about the evolution of a new system.

Debjani Bhattacharyya: Thank you so much, Brian, for the generator. I grew up with one in India, or I should say I grew up with a desire for one because my neighbours had it and we didn’t, and it mediated social class structures. The social capital was built on who had the generator, who would open the windows for you to watch their television and who wouldn’t.

Nils Güttler: Brian briefly mentioned the French philosopher Michel Serres (1930–2019) as an important reference for his work. Can both of you give us a little more insight into your intellectual biographies? Which approaches were formative for you in pursuing this shared interest in history and anthropology?

Debjani Bhattacharyya: For me, that distinction between history and anthropology was never there. Most of my supervisors came out of the Ann Arbor history-ethnography program, precisely because they were historians of Africa and South Asia who have thought very carefully about questions of silences and erasures within the archive. Since the 1990s, there has always been a certain kind of historical scholarship that would be impossible without this deep, incestuous and fruitful conversation between anthropologists and historians.6 That was productive and I don’t think I could have even done my own research without it.

In this context, I drew a lot from your work, Brian, on failure and breakdown,7 as well as from legal history. Moreover, I drew on Matthew Hull, Cornelia Vismann, and Annelise Riles and others who wrote about documents and papers.8 Looking at infrastructure in this way, I wrote a different history. Instead of simply talking about my inspiration, I’ll talk about the challenge I faced. When I began working on this project, one of the big questions I asked my material is, why is it that within the literature on South Asia, questions around rights to the city and property are anthropological questions? When it comes to the literature on property, as I explain in detail in my book,9 it seems that historians have been interested in properties as an agrarian issue, whereas anthropologists have been interested in properties as an urban issue. Why this split? What do I draw from this literature with regard to the urban historiography?

In Government of Paper, Matthew Hull argues that there are maps, documents and reports on the one hand, and there is the real life of the city on the other hand.10 Urban historians based their work on these reports to write history, i.e. ideational images of the city. But if we take anthropological scholarship seriously, we know the real life goes on because these reports never have teeth. Therefore, I went to the judicial archives instead of the municipal archives, and that is when my own research questions around urban property market and land broke down, because initially, literally every file I found was debating: is it land or is it water? It almost broke down the logic of everything I thought about what urban property was in nineteenth-century Calcutta. That is when I had to turn to the literature on legal history, environmental history, urban historiography, and the rich anthropology literature on urbanism within South Asia to really go to the material and ask a different set of questions.

Brian Larkin: I may have really the same story in that I came from doing cultural studies at Birmingham and in many respects, I am still doing it. As a graduate student in the 1990s I travelled to Michigan for a one-week symposium, and met the first generation of anthropology-history faculty and graduate students. By the time I finished my degree and got a job in New York at Barnard College, Columbia University, a number of the anthropology-history faculty had moved to Columbia. So as long as I have been there, the Columbia Department of Anthropology has always operated historically as well as ethnographically and archaeologically.

Besides my background in cultural studies, my research has focused on media. Anthropology made me realize that the media theory I had been trained in made totalizing claims as to how media operate, but that these claims were based on how those technologies exist in Europe and America – and they do not exist that way elsewhere. I became interested in media in Nigeria to ask the question, what would media theory look like if we started from Nigeria rather than, say, Europe or the US? At the time in the 1990s, I was strongly influenced by the work of my advisor Faye Ginsburg and the early moment of postcolonial theory, particularly the work of Arjun Appadurai.11 They were pushing back against the eurocentrism of media theory focusing on media forms emerging from the Global South and indigenous movements. My first published work was in this tradition examining the popularity of Hindi Cinema in Northern Nigeria and what this tells us about South-South movements of culture.12 Why do Muslim Africans watch Indian films in a language (Hindi) they oftentimes cannot understand? What does this tell us about global cultural flows and the decentering of the West?

These questions emerged from postcolonialism and are current again with the focus on the decolonial. How do we interrupt our normative ways of conceiving social phenomena by opening up to realities, modes of thought and cultural production from elsewhere? In the 1990s these questions were explored most directly in the journal Public Culture (founded in 1988), driven by the work of Carol Breckenridge and Arjun Appadurai, and whose sub-heading was ›transnational cultural studies‹. At the same time, I was taken by emerging research in what became known as German media theory that focused on the technics of media rather than the message they relayed.13 My turn toward infrastructure took these ideas in a more materialist direction moving from the cultural texts that media circulate to the technologies themselves as they operated in Nigeria. My aim was to bring someone like Friedrich Kittler together with historians of infrastructure in Nigeria such as Ayodeji Olukoju.14 Olukoju’s essay on the Nigerian National Electric Power Authority (NEPA) was a key work for my current research on generators.15

Debjani Bhattacharyya: I would add a little bit of history of science here, specifically John Tresch’s argument of thinking with a cosmogram.16 If you look at a map or an object in this sense, these are not transparent and uncontested encapsulations of the reality on ground. But they are performative claims. They are all entries into debates, as Tresch argues. And this is where the work of the anthropologist enters the space of history.

One of the most recalcitrant texts that emerges out of the documentary regime is the Bengal Alluvion and Diluvion Act in 1820, abbreviated as BADA. If you go to anywhere in Bangladesh or Eastern India today, the villagers will say, is that a BADA zameen? Zameen is a Arabic/Persian word for land, which entered into Bengali legal verbiage during the Mughal period (1526–1858). And BADA is the British technology of occupying this land, which has now entered into the vernacular. Bada also means big in Bengali. It is very interesting, because within these words, you actually see the multiple meanings of these spaces, not just sedimentation of history in this sediment of land as I call it, but also, the sedimentation of legal infrastructure, of property, thinking and speaking of particular kind of technology. This is what a cosmogram allows us to see, these kinds of debates, these assertions within that space.

Lena Kaufmann: Could you say a bit more about the immateriality and materiality of infrastructures, also in relation to the possibilities of failure and the agency of these infrastructures? Maybe they once had a very colonial idea behind them, but then become translated into a new environment and develop their own agencies.

Debjani Bhattacharyya: This question about the materialities and the immaterialities comes out of my new work in thinking about financial tools, going back to the 1770s–1780s and looking at various kinds of financial insurance infrastructures to translate the winds and the shoals into an economic idea or calculable idea of damage. In that process, what is getting drawn? What actors are getting drawn, what spaces are getting drawn, what calculative and financial units are being delineated?

As a historian, I work with a lot of documents, for instance The Naval Magazine of London and the Almanacs of Bombay, Canton, Bengal, Madras, which included ›rates of premia‹, which is the rates for freight and insurance any shipper would use. The entire rates of premia were completely broken down into wind patterns and seasons. These documents, in other words, translate a particular natural world consisting of cyclones and hurricanes into an economic world, aiming to overcome the ecological limits of cyclones. And overcoming them meant translating cyclone damages into a kind of a financial loss that is recuperable. The sources allow me to understand how a certain kind of a commodity frontier on wind and tides and waves was created at the time. I look, for instance, at the marine court that actually mediates the worlds of finance and oceanic trade. Every time there is a shipwreck it ends up in the marine court, where adjudicating these cases require them to also produce knowledge about the phenomenal world of hails and storms. The courts then become ›jurisgenerative‹ spaces for knowledge production.

In recent years, sociologists have increasingly turned to financial tools like weather derivatives, carbon trading, various kinds of instruments of taxes, carbon taxes and loss and damage and the trading in carbon to basically tackle climate prices.17 This is shaped by twentieth-century climate and atmospheric sciences, and the contemporary political economy and geopolitics shape the science. As a historian, I come to this literature and say, you can actually go back to an earlier period when meteorological science is being produced in a very different setting – often outside the university or Royal Societies. They are being produced in the marine courts and insurance offices. For instance, I look at a series of insurance contracts and documents as well as actuary tables as tools that light up a certain kind of world, a certain kind of organisation of knowledge system, to think through the materiality and the immateriality. And if you turn to financial tools – both then and now which shaped knowledge practices around weather and climate, you see a kind of commodity frontier began to emerge around ecological turbulence. That allows me to return to the present moment where climate and capital are converging in disturbing ways.

Brian Larkin: I can relate to these examples, partly because I have taught for many years a class on the politics and ›poetics‹ of infrastructure. One of the central questions we examine is what constitutes an infrastructure. Most commonly, infrastructure refers to large-scale technical systems.18 But as Debjani is arguing, those systems cannot exist without a financial and legal infrastructure that makes those systems possible. Does the infrastructure of a road refer to concrete and asphalt, the financial instruments that make that concrete possible, or the labor that builds it? The definition of what an infrastructure ›is‹ can be less clear than we usually think, and which issue we focus on depends on the questions a scholar is interested in rather than an ontological definition of infrastructure itself. All infrastructures have their own infrastructures. This creates an unstable definition but, for myself, I prefer to stay with that instability rather than trying to resolve it.

While my own research has focused on the materiality of technologies, materiality is only one way in to understanding the work of infrastructures. I mentioned this above in that I remain interested in infrastructures as representational devices that congeal political forces and environment, creating machines that make up the ambient world we live in. Walter Benjamin argued in The Arcades Project that each age has its mode of lighting.19 Each mode of lighting emerges from a broader political economy and, by creating an ambient world, makes that political economy apprehensible to the senses. What did it mean for our world when we shifted from the flickering light of oil lamps to the steady light of gas jets? What does it mean in Nigeria when the steady light of the mains electricity supply has to be replaced by weaker light provided by generators?

Nils Güttler: How do your approaches change the collection and selection of sources? How do we as historians have to rethink our research practices, if we become interested in phenomena like everyday enactments of technologies or different immaterial qualities of infrastructures?

Debjani Bhattacharyya: For someone who is disciplinarily disobedient, as a historian, you enter the archive, you sit with all these papers and there is this entire world of practice you have no access to, and you are trying to reflect about the past through this. All the work on data documents made me aware of the limits of the documents that historians often end up privileging in their writing and in their practice in some ways.

But there is another question. As I was listening to Brian, I was thinking, what is the generator as an infrastructure? There is oil. One can think through the generator as oil, one can take the generator and look at the labour practices. That’s a completely different set of literature that you channel. There are financial instruments that are necessary to put this generator to function. There is the entire world of legal coding. And it is about visual literacy and exceeds visual literacy, because it raises the question: what is it that we see when we are looking at something? This is a kind of epistemological question. For instance, my archival sources did not permit me to capture the other senses such as the auditory which Nancy Rose Hunt does so evocatively in speaking about the acoustic register of violence, or that David Barnes, with regard to smell, does in writing his urban history of Paris.20 Anthropologists have been far more attentive to the other senses.

The epistemological question around visual literacy, though, was very important for me, for example in my work on the almanac.21 It is not like I was necessarily looking at an almanac, but the almanac as a concept imposed on me a different kind of visual literacy to look at this space,22 which was otherwise completely mediated by maps. Many of the places I write about do not exist anymore as physical spaces, because these are sedimentary landscapes. They are only for a certain period of time, twelve years, five years, two years, and then they disappear. So, what do you do? How does a historian write about a place that hardly existed? Nobody created documents. What the almanac then does is that it forces a particular kind of visual literacy and conceptual apparatus that allows me to reconstitute the world around it, to write about it.

Lena Kaufmann: If I understand this properly, this means that when it comes to historical sources, the ›anthropological perspective‹ involves much more than Quellenkritik (source criticism) in the conventional sense, i.e. a critical evaluation of the context, content and meaning of sources. Debjani speaks here of an ›epistemological question‹. Can you agree with this, Brian?

Brian Larkin: Debjani is asking a question about the nature and limits of data and what we can look at to generate primary data from which we can make observations and conclusions. As I understand it, she is arguing that the data we look at – objects, documents, images, oral histories – emerge from and constitute epistemological fields. They are not simply ›out there‹ but must be produced. They also have a dual existence. For Debjani an almanac is a thing – an object with its own materiality, form, traditions of reading and use and so on – and it is a concept. Similarly, for me, the generator is a device built to create electricity. But, as it is a device tied to the failure of the electric network, and thus the failure of the nationalist state, it points to those political ambitions and their foreclosure.

I know you want us to tease out the distinctions between an anthropological and an historical approach to infrastructure but, to my mind, we are making similar arguments. We are both ›disciplinarily disobedient‹ in not sticking to the canonical methodologies of our fields; we are drawing on anthropology, history, media theory, visual culture, religion, and law, depending on where the issue at hand takes us.

There are also new sets of questions about epistemology being brought by the decolonial turn. If we take Debjani’s example of the term BADA zameen, that is a phrase that enters into Indian history through a Persian and a British history. She ties it to a legal world made up of Mughal administration, British colonial rule, French physiocratic ideas and, no doubt, Islamic law, creating what she terms a ›deeply plural zone‹. The decolonial turn privileges alternative epistemologies that derive from indigenous worldviews and which can offer an alternative to the violence of coloniality. Walter Mignolo referred to this as ›delinking‹ from Western epistemologies.23 This has been contentious for some African scholars who argue that British colonial rule was based on the administration of difference, separating native populations from each other and from British subjects.24 Achille Mbembe argued that studies of tribal worldviews, the production of maps, and linguistic grammars were part of a long history whereby Africans were depicted as separate from the world, and that insisting on the uniqueness of different groups produces a ›metaphysics of difference‹.25 This is an important debate that was also present in postcolonial thought. It asks us to be critically reflexive about the knowledge sets we bring to bear to understand phenomena and how others might think this differently. But, as the term BADA zameen suggests, all sorts of traditions collide and become entangled.

I see the decolonial, along with the anticolonial and postcolonial, as pursuing questions of social justice from different routes. They approach these issues differently, but are animated by similar aims. In my own research I have recently been returning to the older paradigm of political economy that dominated these debates (particularly in Africa) before the shift toward epistemology, power and knowledge that began with Edward Said’s turn toward Foucault and was expanded in a formidable series of theoretical, historical, and literary works.26 In those times, to understand social injustice it was not a question of knowing things but counting things. Where is value produced? Where does it go to? Who does it benefit? Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi, André Gunder Frank, Walter Rodney, Immanuel Wallerstein and the generation of scholars driving these questions were all economists, economic historians or economic sociologists, and while they were concerned with epistemological questions, these were not the prime driver of their work.27

Debjani Bhattacharyya: If we go back to that term, BADA zameen, I think what Brian raises is unfolding in India at the moment: erasing the Mughal and Islamic history, heritage and language practices from our history books and public discourse. And here I think the decolonial approach becomes problematic, especially from the South Asian context, because it is now the project of our Hindu nationalist state to erase our Islamic history in the name of decolonizing the Indian mind. I, as a South Asian, have to always be sceptical of the decolonial approach because of the history that forged me and the present that I inhabit in my country.

I think I never quite left that early postcolonial moment that was deeply grounded within political economy. With the publication of the fourth volume of the Subaltern Studies collective in 1984,28 postcolonial histories from South Asia made a Foucauldian-Saïdian turn to understanding culture. That is very important in that sense. How do we think of value both in a cultural and economic sense? It remained in some way locked. And now I see a lot of my colleagues going back to questions of political economy.

Brian Larkin: As a scholar, I am interested in borrowing and mixing as cultural, religious and social forms circulate from one domain to another. For instance, in my research on religion and media – which is historical and ethnographic – I move away from the focus on opposition and distinction which often characterizes religious movements. This is the way scholars will analyze the difference between Sufi and Salafi Muslim groups, or between Muslims and Christians. There are, of course, strong differences between these movements, particularly in Nigeria, which has been marked by devastating religious violence. The same can be said for the difference between Muslims and Hindus in India. But the focus on difference can obscure the constant borrowing between religious movements and between the religious and secular world. There is a lability to forms that circulate across differing religious domains that gets hidden by the emphasis on distinction and opposition. Sometimes these borrowings are marked and highly contentious. At other times they pass by unnoticed. And, at the most interesting level, sometimes religions evolve together through this mutual borrowing while maintaining a discursive emphasis on separation.

To give one example, I have been looking at this process through the use of public sound. Does the religious use of public sound emerge from Islamic or Christian theology? Is there a dispensation to use (or prohibit) sound that derives from a Salafist or Sufi tradition? Or from traditional religions (in the case of many African nations)? There has been a great deal of scholarship examining this in recent years.29 As machines, loudspeakers had a colonial history, introduced as public address systems to serve secular colonial administrative needs. As such, there was a concept of the ›public‹ and of political citizenship engineered into the object of the loudspeaker, as well as into the concept of what ›listening‹ means.30 But many Muslims in the North of Nigeria today associate the loudspeaker with the Salafist revival, just as many southern Nigerians associate it with Pentecostalism. There has been a movement of the loudspeaker (and the concept of public address) between secular, Muslim, and Christian communities in which each has borrowed from the other in evolving a common repertoire of what it means to broadcast public sound in Nigeria today. I am interested in those forms of mixing rather than emphasizing modes of distinction.31

Nigerian urban landscapes are saturated with

religious sounds emanating from mosques and churches,

itinerant preachers, processionals carrying portable bullhorns, and cars with

large speakers fixed to the top relaying Christian and Muslim preaching.

(photo: Brian Larkin)

Nils Güttler/Lena Kaufmann: Thank you very much, Debjani and Brian, for this conversation. Perhaps it is time to abandon the idea that anthropology and history must ›meet‹ and then return to their respective disciplines, but rather to accept and encourage this ›mixing‹ as an original mode of research.

Notes:

1 Jürgen Kocka, Gruss an den Autor, in: Rudolf Braun, Von den Heimarbeitern zur europäischen Machtelite. Ausgewählte Aufsätze, Zurich 2000, p. 7; quoted after: Jakob Tanner, »Das Grosse im Kleinen«. Rudolf Braun als Innovator der Geschichtswissenschaft, in: Historische Anthropologie 18 (2010), pp. 140-156, here p. 141 (our translation). See also the introduction to this special issue.

2 For history and anthropology respectively, see, among others, Dirk van Laak, Infrastructures, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 20 May 2021; Kregg Hetherington (ed.), Infrastructure, Environment, and Life in the Anthropocene, Durham 2019.

3 Debjani Bhattacharyya, A River Is Not a Pendulum: Sediments of Science in the World of Tides, in: Isis 112 (2021), pp. 141-149.

4 Brian Larkin, Signal and Noise. Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria, Durham 2008.

5 Michel Serres, Le parasite, Paris 1980.

6 Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past. Power and the Production of History, Boston 1995; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, The Rani of Sirmur: An Essay in Reading the Archives, in: History and Theory 24 (1985), pp. 247-272; Anjali R. Arondekar, For the Record. On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive in India, Durham 2009.

7 Brian Larkin, The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure, in: Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013), pp. 327-343.

8 Matthew S. Hull, Government of Paper. The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan, Berkeley 2012; Cornelia Vismann, Files. Law and Media Technology, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, Stanford 2008; Annelise Riles (ed.), Documents. Artifacts of Modern Knowledge, Ann Arbor 2006.

9 Debjani Bhattacharyya, Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta. The Making of Calcutta, Cambridge 2018.

10 Hull, Government of Paper (fn 8).

11 Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Minneapolis 1996; Faye Ginsburg, Indigenous Media: Faustian Contract or Global Village?, in: Cultural Anthropology 6 (1991), pp. 92-112; Faye Ginsburg, Culture/Media: A (Mild) Polemic, in: Anthropology Today 10 (1994) issue 2, pp. 5-15.

12 Brian Larkin, Indian Films and Nigerian Lovers: Media and the Creation of Parallel Modernities, in: Africa. Journal of the International African Institute 67 (1997), pp. 406-440.

13 The classic texts are Friedrich Kittler’s Discourse Networks 1800/1900, trans. Michael Metteer with Chris Cullens, Stanford 1990, and Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz, Stanford 1999.

14 Ayodeji Olukoju, Infrastructure Development and Urban Facilities in Lagos 1861–2000, Ibadan 2003.

15 Ayodeji Olukoju, ›Never Expect Power Always‹: Electricity Consumers’ Response to Monopoly, Corruption and Inefficient Services in Nigeria, in: African Affairs 103 (2004), pp. 51-71.

16 John Tresch, Technological World-Pictures: Cosmic Things and Cosmograms, in: Isis 98 (2007), pp. 84-99; John Tresch, Cosmologies Materialized: History of Science and History of Ideas, in: Darrin M. McMahon/Samuel Moyn (eds), Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, New York 2014, pp. 153-172, here p. 163.

17 Kean Birch/Fabian Muniesia, Assetization. Turning Things Into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism, Cambridge, Mass. 2020; Melinda Cooper, Turbulent Worlds: Financial Markets and Environmental Crisis, in: Theory, Culture & Society 27 (2010) issue 2-3, pp. 167-190.

18 Thomas Parke Hughes, Networks of Power. Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930, Baltimore 1983.

19 Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Cambridge, Mass. 1999. See also Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night. The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century, trans. Angela Davies, Berkeley 1988.

20 Nancy Rose Hunt, An Acoustic Register, Tenacious Images, and Congolese Scenes of Rape and Repetition, in: Cultural Anthropology 23 (2008), pp. 220-253; David Barnes, The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs, Baltimore 2006.

21 Debjani Bhattacharyya, Almanac of a Tide Country, in: items. Insights from the Social Sciences, 10 November 2020.

22 Gautam Bhadra, Pictures in Celestial and Worldly Time: Illustrations in Nineteenth-Century Bengali Almanacs, in: Partha Chatterjee/Tapati Guha-Thakurta/Bodhisattva Kar (eds), New Cultural Histories of India. Materiality and Practices, Delhi 2014, pp. 275-316. For a more in-depth treatment see Gautam Bhadra, Nyara Battala Jay Kaybar [How many times does one with a shaved head go under a banyan tree], Kolkata 2011.

23 Walter D. Mignolo, Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-coloniality, in: Cultural Studies 21 (2007), pp. 449-514.

24 The classic work here is Mahmood Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject. Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism, Princeton 1996. See also Karuna Mantena, Alibis of Empire. Henry Maine and the Ends of Liberal Imperialism, Princeton 2010.

25 Achille Mbembe, African Modes of Self-Writing, trans. Stephen Rendall, in: Public Culture 14 (2002), pp. 239-273.

26 Edward Said, Orientalism, New York 1978. On epistemic violence, see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Can the Sulbaltern Speak?, in: Cary Nelson/Lawrence Grossberg (eds), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Basingstoke 1988, pp. 271-313.

27 Samir Amin, Unequal Development. An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism, trans. Brian Pearce, New York 1976; Giovanni Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century. Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times, London 1994; André Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America. Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil, New York 1967; Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, London 1972; Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World System. Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World Economy in the Sixteenth Century, New York 1974.

28 Ranajit Guha (ed.), Subaltern Studies IV. Writings on South East Asian History and Society, New Delhi 1985.

29 See, for instance, Justice Anquandah Arthur, The Politics of Religious Sound. Conflict and the Negotiation of Religous Diversity in Ghana, Berlin 2018; Marleen De Witte, Accra’s Sounds and Sacred Spaces, in: International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32 (2008), pp. 690-709; Murtala Ibrahim, The Clash of Sound, Image and Light: Inter- and Intra-religious Entanglements and Contestations during Mawlud Celebrations in the City of Jos, Nigeria, in: Africa 92 (2022), pp. 759-779.

30 See Charles Hirschkind, The Ethical Soundscape. Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics, New York 2006; Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past. Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, Durham 2003.

31 Brian Larkin, Techniques of Inattention: The Mediality of Loudspeakers in Nigeria, in: Anthropology Quarterly 87 (2014), pp. 989-1015.