‘There is something in the spirit of Egyptians that is unique, profound and light-hearted. Other countries have money – we have humour.’

(Amr Selim, Egyptian caricaturist)1

1. Caricatures and Their Importance for Studies in Contemporary History

Caricature can be defined as an art engagé which aims to transmit a social or political message. In order to achieve this goal, the satirical picture triggers an emotional reaction in the audience and guides it through a cathartic coming-of-awareness process. The feelings evoked by caricature must not necessarily be expressed through laughter; but they are a joyful or indignant shock reaction to gazing at something absurd. William A. Coupe, following Schiller, therefore defines the nature of caricature as the outcome of a dialectical struggle between the ideal and the real: ‘This conflict of ideal and real may, however, be seen and expressed in two different ways, in an emotional and serious or in a humorous and jesting fashion.’2

If one bears in mind the Italian root of caricature, which is the verb caricare (to load, to charge), the corresponding noun could be either overload or overburden. ‘Caricature is therefore a depiction in which the natural balance is consciously disturbed by the overloading of certain parts. When it is transposed into the graphic field, ‘overload’ becomes ‘exaggeration’.3 The artist who draws a caricature operates with different tools of exaggeration. Already existing asymmetries – which might be of socio-political or biological nature – are singled out and overloaded. The esthetical symmetry of the composition is disturbed and pushes its meaning towards the absurd. This exaggeration of an asymmetrical aspect of the composition might be achieved through a graphic deformation – such as the transformation, dislocation or disguise of the figures – or by adding a text.

Another important feature of satirical pictures is the immediateness and briefness of their significance. This is especially important when we deal with political caricatures in times of fast and fundamental political changes. Under exceptional circumstances the specific meaning of a propagandistic, satirical drawing might achieve its goal overnight and afterwards become obsolete or completely different in nature. As Lawrence H. Streicher rightly underlines: ‘Caricature and cartoons […] do not aim at the ‘immortal art’ aspect of the cult of beauty but at influence and political practice.’4 However, the specific deadline of the applicability of a particular satirical drawing depends on the pace of socio-political change. This is the reason why the caricatures drawn by the Egyptian caricaturist al-Hegazi5 (b. 1940) in the mid-1960s, criticizing the baby boom or the extreme crowdedness of public transport in Cairo, are still applicable to the situation of the country even nearly half a century later. On the other hand, the portrayal of the hardships endured by people queuing in front of the socialist cooperatives (gam‘iyyat 6) during Nasser’s regime completely lost their significance with the beginning of Sadat’s economic open door policy (infitah).7

2![]()

Caricatures can therefore be useful sources in our understanding of a specific historical epoch. As Ursula E. Koch puts it: ‘Historical or contemporary politico-journalistic caricatures […] reflect the zeitgeist and contribute to its development. By using codes and symbols of common knowledge they unmask political and social contradictions and misdeeds. [Therefore], for some time now, they have been rightly used as important source material.’8

2. A Short Approach to the History of Caricature in Egypt

In Egypt, although it is certainly possible to trace the history of caricature back to Pharaonic antiquity, the modern sources of this art can be found in the diverse genres of (Egyptian) Arabic satirical and mostly performed literary compositions – such as the classical maqama and the hija’, the more form-free stories (especially about the famous anti-hero Joha), the ubiquitous proverbs and nuktas,9 the colloquial zajal (rhyme-prose) poetry and popular songs. To this list the shadow plays (khayal az-zill), the puppet shows (qaraqush) and the life-staged farces can be added. By the end of the nineteenth century, inspired by European satirical magazines such as the French Charivari, the British Punch and the Italian Fanfulla, the Egyptian sense for satire had found another medium for expression.

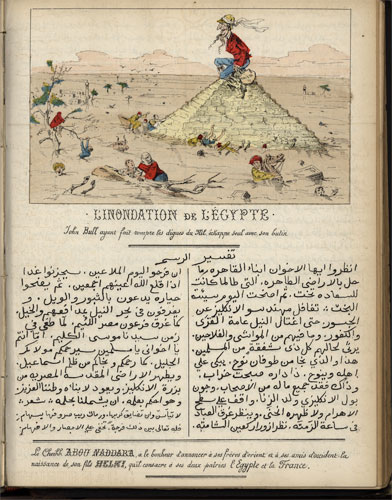

James Sanua (1839–1912), an Egyptian playwright who had worked in colloquial theatre and was at the same time acquainted with the European satirical magazines of his times, announced his intention to publish caricatures in the first issue of his newspaper Abu Nazzara Zarqa (The Man with the Blue Glasses) on 25 March 1878. He actually published the first caricature five months later in his Parisian exile, and his satirical Abou Naddara series continued until 1910. After an experimental phase of simple cartoons drawn by Sanua himself, already by 1887 the artistically accomplished lithographs published in Abou Naddara had nothing to envy the Charivari or the Punch. The coloured caricature of John Bull who broke the dams, caused a flood, but happily escaped to the top of a pyramid with his booty, is an example of the high level of this art in the Abou Naddara journals.

3![]()

In 1907 another multilingual illustrated magazine appeared, simultaneously entitled as-Siyasa al-Musawwara (Politics Illustrated) and The Cairo Punch.10 Only four years later French diplomacy apparently found the anti-colonialist stance of its lithographs dangerous enough for its interests to enhance the counter-print and diffusion of images that glorified the ‘Grande Nation’.11 Like Sanua, A.H. Zaki, the publisher of this Egyptian Punch, went into exile and henceforth published from Bologna.

Due to the reintroduction of the 1881 press law by Sir Eldon Gorst five years before the outbreak of the First World War, Egyptian caricatures started to really unfold their propagandistic potential only by the 1919 Revolution. The Egyptian journalist and caricaturist Ahmad an-Na‘im claims that ‘right from the beginning, journals were not interested in using caricatures as gap fillers or funny pictures […]. Rather, caricatures were to play an active role in the [daily] events and propaganda in the nationalistic period which Egypt underwent before and after the revolutionary uprisings […].’12

In 1921, the satirical magazine al-Kashkul was founded as the voice of the Wafd Party, which initially fought for Egyptian independence from the British. The Spaniard Juan Sintes, teacher at the new Royal School of Arts, was hired in order to draw the caricatures. Two years later the newspaper Ruz al-Yusuf appeared to compete with al-Kashkul. The charismatic founder, the actress Fatma al-Yusuf (1898–1958), guaranteed the success of her journal right from the beginning by hiring the Armenian artist Alexander Sarukhan (1898–1977). Sintes and Sarukhan, together with Rifqi, who had flown from Turkey to Egypt, were the foreign fathers of modern Egyptian caricature. They taught the first generation of Egyptian caricaturists, Rakha (1911–1989), ‘Abd as-Sami‘ (1916–1985), Salah Jahin (1930–1986) and George Bahgouri (b. 1932), whose cartoons were eagerly followed in different newspapers and satirical magazines.

4![]()

The period between the Second World War and the Young Officers’ Revolution was a golden age for Egyptian caricature. Artists freely drew satirical pictures with political content. Ruz al-Yusuf repeatedly made use of the personification of the little man of the street (al-Masri Efendi), originally designed by Sarukhan in 1934, in order to criticize national and international politics.

This fruitful period of political cartooning, during which no public figure was spared mockery by the vast number of satirical as well as ‘serious’ newspapers, came to an abrupt end when Nasser brutally curtailed the freedom of the press in 1955. Nonetheless, one year later, a new journal called Akhbar al-Yawm (News of the Day) appeared under the umbrella of Ruz al-Yusuf which, according to Charles Vial, set the beginning for a new school of Egyptian caricature.13 Bahgat ‘Uthman (1931–2001) and Ahmad Hegazi (b. 1940), among others, focused on social topics and expressed their political stances under the double disguise of caricature and the reinterpretation of the political within the social field.

Caricatures of political leaders, still common by the end of the 1940s, disappeared shortly after Nasser’s accession to power. It was not until approximately forty years later that Mustafa Hussein’s (b. 1940) anti-hero Kambura broke this taboo. Even though Kambura’s identity was kept fictional, his activities were visibly political in nature. In one cartoon series, he tried to get elected to parliament by any means and even contracted different professors to teach him rhetoric and to explain this strange word democracy to him, which Kambura had initially taken for a special kind of caviar.14 While Bahgat ‘Uthman silently contrasted the bad police officer with the poor fallah (peasant), Ahmad Ragab provided Mustafa Hussein’s corrupt public figure Kambura with dense speech.

5![]()

Over the past decade a new generation of artists has emerged who began their work for the press of the opposition, among them the first female caricaturist, Doaa al-Adl. They started to re-approach political topics, but without pointing the finger directly at Mubarak or his regime. They criticized their hardships in an abstract and terrifyingly holistic manner. In 2008 Doaa al-Adl drew a black tsunami composed of eight grinning faces and greedily snatching hands that threaten a poor man in mended clothes on a wooden boat. This attack against corruption was anonymous enough for the state-held newspaper al-Ahram to publish it together with an article about the artist.15 Thus, even though corruption, the system, the situation as well as – on a less abstract level – the Muslim Brotherhood were criticized by caricatures published during the Mubarak era, the image of the president remained strangely sacred. Often framed in royal gold, Mubarak smiled from thirty-year-old yellowish pictures that decorated all the dirty, shabby grey walls of public institutions.

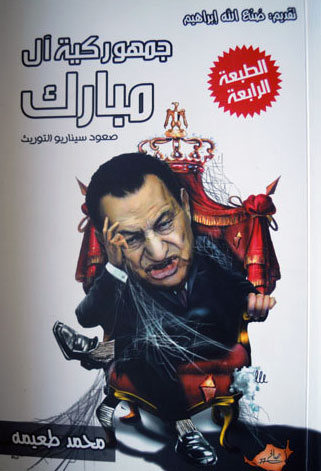

Only very shortly before the revolution, on the cover page of the satirical treaty against Mubarak Junior’s succession to the Egyptian throne, an aggressive caricature seemed to open up Pandora’s Box of previously restrained Egyptian anger. It was entitled The Re-Kingdom of the Mubarak Family – Presentation of an Inheritance Scenario, and the introduction was written by the famous novelist Sun‘allah Ibrahim. Mubarak, with a horribly deformed face, is sitting on the damaged throne of the Egyptian Republic-Kingdom. The projected stagnation of this hybrid regime is highlighted by the spider webs that cover even the immobile autocrat himself.

3. Caricature and the Revolution of 25 January 2011

The Egyptians’ uneasiness with their political regime started long before 25 January 2011 and found its daily expression in the steadily multiplying Mubarak jokes, a massive increase in literature with satirical content and through caricature. The authoritarian regime tried to enhance its pseudo-democratic appearance by quietly contemplating but strictly monitoring the rise in opposition magazines and editorial houses such as Dar ash-Shuruq and Mayrit. Therefore, in 1990 the journal Karikatir was founded, entirely dedicated to this art engagé, and on 1 January 2011 a satirical comic magazine appeared under the title Tuktuk.16 However, the printed press of the opposition was not the most important distributor of caricatures. Satirical pictures massively appeared on Facebook walls, where they were eagerly shared and discussed.

6![]()

As we know, during the most intensive days of the Egyptian revolution,17 from 28 January until 11 February, a great number of people gathered on Cairo’s Tahrir Square without knowing whether they would return home alive. They were aware of this danger and even willing to die for the freedom of their nation. By 2 February, later dubbed the battle of the camel, when Mubarak had the baltagiyya (thugs) violently attack the demonstrators, everybody had witnessed other people being injured or even killed. Contrary to the expectations of the power holders, the demonstrators were not scared off; they even wrote their revolutionary slogans directly on the tanks, which had been threateningly positioned around the square.

In this so entirely exceptional situation, caricature was continuously composed by whoever felt like expressing him- or herself in this way. Pictorial satire had escaped the restrictive frame of printed paper. More or less artistically accomplished caricatures were painted on walls, printed or drawn on T-shirts and banderols, animatedly staged by groups, individuals or with puppets, and even symbolically interpreted.

Not only was the president’s imagined tomb provocatively put on the same level as a pile of rubbish, but pictures of Mubarak himself were violently deformed and disfigured with a pirate’s eye patch or Hitler’s moustache. Loyal to the original feature imprinted into caricature by the pioneer Carracci movement against the idealism of Renaissance paintings, this genre came to tear down the unrealistic, iconographic image of the never-aging Hosni Mubarak and to finally unmask the true, evil face of the Egyptian Dorian Gray.

7![]()

On Tahrir Square, caricature had come to play three different roles. Firstly, satirical drawings were coined as a political weapon by means of which the president was to be forced into resignation. With this aim, people used whatever they had in order to produce satire; they even turned themselves into embodied caricatures. A young man, for example, circled the square with a paper that read: ‘step down, my hands are hurting [from holding up the banner]!’ Another thought that the contemporary authoritarian Pharaoh might better understand the message of his people if it was written in Hieroglyphs.

Secondly, caricature and enacted satire helped Egyptians to keep their spirits of resistance high. Especially spontaneous parodies of the president, where one or two people performed and the crowd could shout back at them, were extremely helpful for this purpose. In order to make the demonstrators endure the long hours of waiting and the constant feeling of threat on the square, artists typically performed sketches, poems and songs with satirical content. And thirdly, banners with caricatures and satirical texts were used in order to transport the message to the outside – back home to the family as well as to potential (foreign and national) allies. This is the reason why translations into various languages were to be found and, later on, even caricatures of international provenance, e.g. by the famous Brazilian activist Carlos Latuff.

(Film and subtitles: Eliane Ursula Ettmüller)

After Mubarak’s resignation on 11 February 2011, caricature had to find a new focus. Satirical pictures came to summarize recent history, to celebrate victory and to socio-psychologically deal with the revolutionary experience. Newspapers freely and extensively produced caricatures; even the journals formerly most loyal to the government did not think twice before openly celebrating the victory of the revolution and mourning its martyrs. At the same time Facebook, as usual, (re)distributed the images, and exhibitions of revolutionary art were held in galleries.

8![]()

One such exhibit was called Caricatures of the Revolution, and was organized by the founder and director of the Egyptian Caricature Museum Fayyum, Mohamed Abla.18 In Cairo Atelier, mostly copies of previously published caricatures by different artists were exhibited from 14 until 27 March.19 Three topics were especially prominent in the repertoire of the artists’ works. The first was Mubarak’s stubbornness in vacating the Egyptian throne and the victory of the crowd, now united as the Egyptian people on the mythical Liberation Square.

The second motif glorified in the aforementioned exhibition was Facebook. It was publically celebrated as both: the one and only trustworthy Egyptian news channel and the most effective network for political propaganda. The caricaturist Makhlouf metaphorically depicted Facebook as the knight who came to free the country while Amr Selim drew Facebook as the direct substitution of the Mubarak icon in its former position as the official office picture.

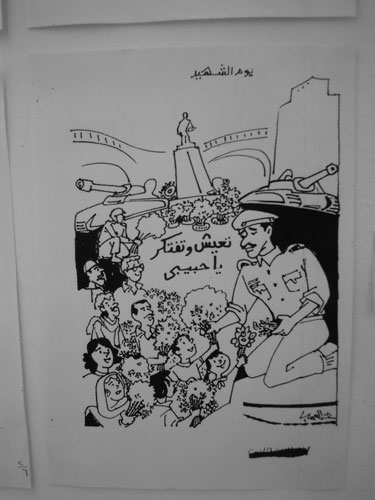

A third important topic depicted by the caricaturists was the population’s change of attitude towards the police. Amply feared before the revolution, the satirized officers now served coffee and politely greeted the people, who looked down on them. At the same time the police was mocked, the army was overwhelmingly celebrated as the liberator of the nation. Consequently, and much more so than Selim’s Facebook drawing, the image of the soldiers, solemnly decorated with flowers and posing together with the victorious Egyptian youth, came to replace the former idealized picture of Mubarak.

9![]()

Posters were sold on Tahrir Square that amply glorified the unity between the army and the people. However, this honeymoon was not to last for long and Tuktuk already challenged the pure image of the armed forces on the cover page of its second issue, published in May: Mubarak’s criminal allies were depicted as consisting of the baltagy (thug), the riot policeman, television and, last but not least, the grim-looking soldier.

Caricatures played a pivotal role as carriers of propaganda in all the revolutionary movements that have recently unfolded in the Maghreb and the Middle East. They were easily spread via the Internet and have not only contributed to the formation and articulation of public opinion in one country, but also translated the revolutionary ideas into a global understanding of the ‘Arab Spring’.

Drawings have also adapted and played with symbols formerly used in other critical situations. The Jordanian artist Omar Abdallat for example integrated the well-known character Handala into his pictorial satirical repertoire. The drawing of the barefooted, ten-year-old Palestinian refugee boy, who stands with his back to the audience, was first used as an alter ego and signature by his creator Naji al-Ali (1938–1987). However, Handala’s fame quickly spread and he became an allegory of the struggle for a Palestinian state. In Omar Abdallat’s adaptation, Handala is finally victorious and able to destroy with his stone the vain and decrepit statue of the ‘Idols of the Arab World’.20 As a matter of fact, Mubarak’s strangely untouchable iconographical image of the always young and smiling hero was – not only in caricature – transformed into that of an old villain in agony on a hospital bed in a cage before the judge.

However, we should not forget that the outcomes of many of the revolutionary movements in Arab countries – including in Egypt – are still far from decided. In many places, the idolized images of potentates still inhabit a quasi-sacred position. On 26 August 2011, the Syrian artist ‘Ali Firzat was severely tortured for his ‘heretical’ attempt to visually satirize Bashar Assad. The commentator of the Cairo weekly Sawt al-Umma therefore recalled the worldwide dispute about the Danish caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad and furiously concluded that ‘humorous pictures which criticize the tyrannical Arab rulers seem to be considered much more of a crime than the sacrilegious pictures of the Prophet’.21

In Egypt, half a year after the revolution, the candidates of the 220 new political parties, the representatives of other interest groups as well as independent citizens continued to use caricature in order to attract the attention of their audience. Freed from censorship, all media were easily available for the dissemination of satirical images. Nonetheless, after the first euphoric phase of victory, a certain void has opened up and Egyptian caricature has gone back to targeting an anonymous enemy such as al-baltagy (the thug) or ‘the corrupt one’. A generalized socio-political melancholy seems to hold the country in its grip and the nostalgically tainted phrase ‘that was before the revolution’ can be heard more and more often. Who can be made responsible for today’s miserable situation? At the demonstrations on 9 September 2011, the owner of a restaurant insightfully mocked the Egyptians’ self-deception, now deprived of their father figure who could so easily be blamed for all the misdeeds of the last three decades. He therefore hung a soft-toy-camel from a tree with a sign around its neck that read: ‘I am the sole [i.e. I am solely] responsible for everything!’

1 Quoted by Osama Kamal, Of Cartoons and Revolution, in: al-Ahram Weekly Online, 3-9 March 2011, No. 1037, URL: http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/Archive/2011/1037/cu2201.htm.

2 William A. Coupe, Observations on a Theory of Political Caricature, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 11 (1969), pp. 79-95, here p. 89.

3 Franz Schneider, Die politische Karikatur, München 1988, p. 32. All translations are mine.

4 Lawrence H. Streicher, On a Theory of Political Caricature, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 9 (1967), pp. 427-445, here p. 433.

5 I adhere to the commonly known transliteration of names and journal titles used by the Egyptian artists and publishers themselves.

6 For the sake of easier readability, transliterations are rendered as simple as possible. Specificities of the Egyptian (Cairene) dialect, such as the letter ج (jim), which is pronounced g, are mirrored.

7 For an approach to Ahmad Hegazi’s work from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, see Charles Vial, Cairicature, Cairo 1997.

8 Ursula E. Koch, Marianne und Germania in der Karikatur (1550–1999), Leipzig 1999, p. 5.

9 Afaf Lutfi Al-Sayyid Marsot suggests that the Egyptian nukta must be considered something more than a mere joke, namely ‘a state of mind, a farce in capsule form, or instant satire. It is endemic in Egypt, arises at the least or the slightest provocation whether of a private or a public nature, and rises to dizzy heights of virtuosity in times of crises’. Afaf Lutfi Al-Sayyid Marsot, The Cartoon in Egypt, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 13 (1971), pp. 2-15, here p. 6.

10 Marilyn Booth, What’s in a Name? Branding Punch in Cairo, 1908, paper at the workshop ‘The Power of the Image – Caricatures as Transcultural Media of Political and Social Propaganda in the Era of Imperialism and Colonialism’, Fayyum 2011.

11 Christopher Harrison, French Policy towards Islam in West Africa, 1860–1960, Cambridge 1988, p. 52.

12 Ahmad ‘Abd an-Na‘im, Hikayat fi l-Fukaha wa-l-Karikatir [Stories in Humour and Caricature], Cairo 2009, p. 11.

13 Vial, Cairicature (fn. 7), p. 16.

14 Amr Helmy Ibrahim, La Caricature Politique en Egypte, in: Jean-Claude Vatin (ed.), Images d’Egypte. De la fresque à la bande dessinée, Cairo 1991, pp. 105-131, here p. 110 and p. 112 (fig. 5).

15 Amira El-Noshokaty, Girls can Make you Laugh, too, in: al-Ahram Weekly Online, 3-9 December 2008, No. 925, URL: http://www.masress.com/en/ahramweekly/5795.

16 The journal was named after the three-wheel taxis imported from India, whose numbers have been steadily increasing on the streets of Egypt.

17 Here I would like to thank Dr Nabil Bahgat for sharing with me his extensive photo material taken on Tahrir Square every single day and night of the revolution.

18 I would like to thank Mohamed Abla for giving me permission to photograph all the caricatures of his exhibition and to use them for my work.

19 Unfortunately neither the places (i.e. the journals) where they were firstly published nor the precise dates of their publication were indicated in this exhibition. The problem of missing data of this kind is common to nearly all publications about Egyptian caricature.

20 Omar Abdallat’s caricature of the victorious Handala was published in ath-Thawrajiyya, October 2011, no. 1, p. 12.

21 Sa‘id Wahba, ‘An ‘ar-Rusum al-Musi’a’ li-Bashar al-Assad’ [On ‘the Sacrilegious Pictures’ of Bashar Assad], in: Sawt al-Umma, 9 September 2011, p. 1.![]()