1. The Ascent of Marian Miracles, 1940–1952

2. The Decline of the Marian Movement

3. Therese Neumann: From Obscurity to Beatification

4. Conclusion

The so-called ‘Marian century’ in modern Europe began in 1854 with the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception and climaxed during the decade after 1945.1 European congregations reported thirteen to fourteen apparitions a year to Church officials from 1945–1954; eleven instances occurred in the German Catholic strongholds of Bavaria, the Palatinate, and the Rhineland as well as the West’s most prominent twentieth century case of stigmata.2 West Germany participated in a trans-European revival of religious miracles that occurred while many other Christian religious institutions lost popular support. Overlooked by mainstream accounts of German history, as well as by otherwise thorough research networks on the German Catholic history, this postwar surge in Catholic miracles, nevertheless, captured the attention of a handful of specialists who connect the stunning popularity of the apparition movement to war trauma, anti-Communism, and the Cold War. Building on existing research, this essay argues that a far-reaching movement based around Marian visions and stigmata emerged as a reaction, not only to the Cold War, but also to anxieties about Americanisation, consumerism, and Catholic narratives about the Nazi past. Furthermore, this brief but intense period of faith in the miraculous represented a power struggle within the German Catholic community between traditional male powerbrokers and vulnerable and, primarily, powerless churchgoers over access to spiritual influence.

The historiography on twentieth century apparitions identifies Catholic milieu structures and war trauma as the stimuli for German Catholicism’s attraction to visions of the Virgin Mary. Anna Maria Zumholz addresses Third Reich Marian apparitions within the context of the Catholic milieu, the hegemonic theoretical model for understanding modern German Catholicism. Numerous scholars argue that the Catholic milieu was a transitional subculture that preserved traditional religious values by using progressive organisational methods to combat threats to traditional beliefs and practices.3 Zumholz suggests that in times of crisis, some German Catholic communities formed ‘sub-milieus’ independently of Church hierarchy. Once an apparition gained popularity in the context of dictatorship and war, lower-level clergy and prominent members of the laity created an infrastructure for an enduring circle of followers that persisted into the postwar era.4 Anthropologist Monique Scheer explores how the anti-Communist interpretations of apparitions in Fatima, Portugal during 1917 captured the imagination of German Catholics throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The Vatican revived the cult of the Virgin Mary in the nineteenth century to mobilise support against secularisation. As a result, rural girls throughout Europe claimed to see the Virgin Mary and sometimes the Vatican recognised the visions as legitimate if enough evidence indicated supernatural activity. Church leaders used famous and officially sanctioned apparitions in Fatima and Lourdes (France 1854) to encourage devotion until the second Vatican Council reforms of the 1960s. Scheer suggests that the impetus for Marian devotion came from the Vatican, German bishops, and the Catholic press, but staunch advocates of several unsanctioned apparitions operated beyond the boundaries of Church authority. Scheer argues that the experience of World War II and the fear of nuclear war caused a Catholic ‘reactivation’ of Marian symbols associated with the Thirty Years War. Finally, Cornelia Göksu’s dissertation about the most popular and important postwar apparition at Heroldsbach supports Scheer’s conclusion that faith in apparitions evolved from wartime trauma.5

This article examines popular apparitions in the villages of Heroldsbach (Bavaria), Fehrbach (Palatinate), Niederhabbach (Rhineland), and Rodalben (Palatinate) along with the stigmata of Therese Neumann in Konnersreuth (Bavaria) in order to address new questions about German Catholic faith in supernatural intervention after 1945. While Zumholz, Scheer, and Göksu correctly link belief in apparitions to crisis, dictatorship, and war, the phenomenon stemmed from other causes as well. After the fall of Nazism, German Catholicism faced an ambivalent future in West Germany. No longer a minority, Catholics became a political force within the ruling Christian Democratic Union (CDU) but struggled with three major obstacles. First, they echoed Pope Pius XII’s obsessive concern about atheistic communism and the potential for conflict in the East.6 They feared the growing consumerism and Americanisation that accompanied their western integration as well because it threatened clerical control of moral values.7 Finally, the Church confronted its ambiguous Nazi past by inaccurately depicting religion exclusively as a bulwark against National Socialism. Religious miracles became a forum for rhetoric about not only wartime crises but all three central postwar issues.

2![]()

The rise of apparition movements threatened bishops and urban-based clergy who almost universally condemned them as challenges to their monopo-ly on spiritual authority. Although the Church sometimes endorsed apparitions in other countries if they could advance the Vatican’s agenda, the German bishops viewed such events with suspicion if they embarrassed the Church or threatened hierarchical discipline. They opposed all of the eleven postwar apparitions on this basis. Zumholz’s theory about a sub-milieu offers interesting possibilities for understanding this confrontation between bishops and congregants. However, her analytical model relies heavily on the microcosm of the small town of Heede. The Marian movement developed an extensive network that transcended individual localities or milieus, connecting diverse apparition sites in the Rhineland, Bavaria, the Emsland, and the Palatinate as well as rural pilgrims from Westphalia, Switzerland, and the Netherlands and urban pockets of devotees from Cologne and Düsseldorf. Although the heavier emphasis on Marian devotion in rural Bavarian communities made southern Germany the most fertile ground for popular visions,8 widespread interest stretched to multiple Catholic regions in West Germany.

The use of Pierre Bourdieu’s ideas about ‘religious field’ by sociologists offers a more effective instrument for framing this wider confrontation between Church hierarchy and members of the laity committed to Marian worship. Bourdieu suggests that the ‘religious field’, like all fields that interact with one’s ‘habitus’, is a hierarchical realm of competition between representatives of religious institutions and members of the laity over social ‘legitimation’, potential access to wealth and power, the meaning religion lends to one’s life, and the so-called ‘goods of salvation’, such as sacraments and Church membership. Bourdieu believes that parallels between the class system and the hierarchy of the Church indicate that organised religion usually reinforces the power of existing class structures and political elites. This theory is particularly compelling in the context of West German religious skirmishes about the legitimacy of miracles. During the Adenauer era of the 1950s, which was dominated politically by the CDU, the clergy and middle-class associational leaders shaped local religious life, frequently supporting conservative cultural values and normative family structures. From a Bourdieuian perspective, the attacks by male elites in the Catholic milieu on female seers and vulnerable men, such as concentration camp survivors and prisoners of war, suppressed a symbolic revolt by some of German Catholicism’s most pious believers against a Catholic hierarchy that gained unprecedented power in the Federal Republic.9

In sum, this essay considers existing analyses about the Cold War context in relation to these religious miracles, but also probes less studied motives, such as anxieties about new forms of popular culture and debates about Catholicism under the Third Reich. Furthermore, it addresses the meaning of this wave of apparitions for power relations within the postwar Catholic community, utilising Bourdieu’s ideas about the religious field as a lens with which to analyse conflicts over the legitimacy of Catholic faith in supernatural intervention.10

3![]()

1. The Ascent of Marian Miracles, 1940–1952

The postwar revival of Catholic Marian visions was rooted in the Third Reich. The apparitions seen by four young believers in Heede in 1937 demonstrated how the miraculous became influential in the imagination of the Catholic population in the context of totalitarian dictatorship and looming war. The Heede movement introduced themes that would resonate after the war, emphasising suffering, sin, redemption, and punishment.11 The seers initially utilised the traditional role of girls as conduits for the Virgin Mary in order to accumulate power and subvert the traditional patriarchy of the Catholic Church. They led a challenge against the clerical monopoly on ‘spiritual capital’ and on access to what Bourdieu calls the ‘goods of salvation’. However, even within the context of this attack on clerical authority, these girls accepted and sometimes sought male leadership from their local priest and other notable men from the apparition movement. Rigid gender roles persisted when men institutionalised and validated devotion to the apparitions. The seers and pilgrims of Heede invoked religious symbols and gender norms imitated by the postwar Marian movement.

The Heroldsbach apparitions initiated the postwar confrontation between laity and Church leaders over access to salvation in 1949. By the time of the Blessed Virgin’s tearful farewell to her four female visionaries in October 1952, an estimated 1.5 million pilgrims had visited Heroldsbach to witness its 3,000 apparitions. Heroldsbach’s followers pursued a form of Catholicism based loosely on Vatican policy but free of strict doctrinal and clerical control. Therefore, the diocese of Bamberg and the Vatican condemned their grass-roots movement, eventually excommunicating the local priest, the seers, and forty leading supporters.12 The bitterness of the conflict between pilgrims and institutional leaders became evident when a clerical representative from Bamberg arrived in late October 1950 to announce the Church’s prohibition of the ‘Heroldsbach cult’. Apparition supporters shouted: ‘Get out of here, hypocrite and Pharisee’ and ‘You are the devil’. The police protected him from the angry stone-throwing crowd.13

Heroldsbach distinguished itself from other German apparitions by means of the fervent devotion and strict organisation of its followers. Even observers neutral about other visions commented on the intensity of Heroldsbach’s most avid worshipers. They formed a lay committee (Laienkommission) after the Church forbade the parish priest from leading prayers at the apparition site, attracting pilgrims and other activists from Bavaria, the Rhineland, Westphalia, and Switzerland.14 Several scholars studying both the diocese of Bamberg and other regions of Germany argue that confessional associations and milieu structures remained weak in rural areas with a Catholic majority because the countryside lacked oppositional forces, such as socialism and liberalism.15 Perhaps the Heroldsbach lay leadership became so powerful because long-standing cultural symbols in a region shaped by rural Bavarians’ traditional veneration of the Virgin Mary mobilised the postwar population more than associations in an area lacking organisational infrastructure. With a handful of loyal clergy and a developing network of supporters, publications, and fund raising infrastructure, the Heroldsbach faithful waged a long public relations campaign that challenged the Church hierarchy for what Bourdieu would call ‘spiritual capital’.

4![]()

Numerous spectacular reports support the conclusions of Zumholz, Scheer, and Göksu that World War II and the Cold War stimulated interest in apparitions. For example, at the celebration of the Immaculate Conception in 1949, spectators claimed to witness a solar phenomenon similar to the one over Fatima during 1917. The young seers also sustained dialogues with the Virgin Mary, often articulating anxiety about Russians and Communism. Emulating the anti-Communist message of the Fatima apparitions, German Catholics found foreboding of catastrophic destruction in the visions.16 The proximity of Heroldsbach to the Czechoslovakian border during the Communist consolidation of power in Eastern Europe undoubtedly contributed to these fears of Cold War apocalypse.

Although sometimes excluded from accounts of these events, Heroldsbach activists such as Fritz Müller illustrate the role of Catholic memory about the Third Reich during this confrontation with hierarchal authority. A Rhineland Catholic who saw the Virgin Mary from a hospital bed during World War I, Müller devoted much of his life to publicity for apparition sites. He also rhe-torically bludgeoned the Church with his anti-Nazi credentials for their failure to recognise Marian miracles. Referencing his five-year sentence for spreading propaganda about the Banneux apparitions of 1933 (in Belgium), he wrote: ‘I once had the courage in the death cell of a concentration camp to tell the camp commandant that I would not become a traitor. […] Now more than ever I have reason to avoid the treachery of silence, even when threatened with excommunication.’17 By frequently comparing his time in a concentration camp to the Church’s excommunication of Heroldsbach followers, he linked the heavy-handed reaction of the bishops to the brutality of the Gestapo. Such rhetoric usually neglected the checkered past of some of Heroldsbach’s most important supporters, such as the parish priest in Heroldsbach and the retired theologian and ex-National Socialist supporter Dr. Johannes B. Walz.18

Despite his stated wish for legitimation from clergy, these National Socialist comparisons formed only part of Müller’s relentless condemnations of the German Catholic hierarchy.19 For example, he circulated the following poem entitled, ‘Catholic Existentialism?’:

Man can exist,

If he does not think,

Never think of Heroldsbach,

Otherwise you will be hanged…

Bamberg thinks for everyone,

Rome willingly agrees

Therefore quit your thinking,

So that you will have peace.20

Many Heroldsbach pilgrims became so convinced of their special status that threats of excommunication failed to deter their stinging criticism of Church leaders. In the process, they developed a critique of Catholic hierarchy that demanded agency for members of the laity.

5![]()

Müller’s connection of his imprisonment in a concentration camp with his faith in Marian apparitions illustrates a larger trend among male supporters of Heroldsbach and other visions. Numerous camp survivors and former POWs became prominent as activists and seers at sites of Catholic miracles, linking their personal suffering through war and dictatorship with their attachment to the Virgin Mary. On the one hand, this public embrace of male vulnerability in the context of spiritual mysticism rebuked the martial masculinity of the interwar period. During the 1920s and 1930s, male Catholic youth organisations converged with post-World War I gender norms and rejected feminised Marian piety in favour of street marches, uniforms, and militarised language.21 On the other hand, these former camp inmates also posed a counterpoint to the conservatives and liberals favouring rhetoric about ‘sober’ fathers, ‘reliable’ husbands, and ‘protectors of their families’ in a revival of ‘traditional’ patriarchy after 1945.22 Although not opposed to these notions of masculine respectability during the Adenauer era, male devotees openly espoused forms of spiritu-ality usually labelled effeminate by mainstream Catholics and non-Catholics throughout the twentieth century.

A similar set of apparitions also occurred in a town called Fehrbach in Rhineland-Palatinate at the same time as those in Heroldsbach. A twelve-year old orphan, Senta Roos, saw the Virgin Mary for the first time on May 12, 1949. She visited Heroldsbach, and a network developed between the two towns. Fehrbach pilgrims reported ‘solar phenomena’, and the Virgin of Fehrbach also ominously warned that ‘something terrible’ would happen if pilgrims failed her.23 The Church opposed the vision with the same vigour as it did that of Heroldsbach, threatening its supporters with excommunication.24 Finally, Fehrbach also mobilised a national and trans-European response with worshippers arriving from neighbouring towns, far-flung regions of West Germany, and bordering countries, such as the Netherlands and Switzerland.25

As in Heroldsbach, Fehrbach villagers used their direct access to heavenly figures as well as references to the Catholic-Nazi past to challenge the institutional Church for greater control over spiritual capital. For example, when the Bishop from Speyer demanded that Roos should inform only Church figures about new revelations, she responded that Mary deemed such action unacceptable.26 She provocatively privileged a spiritual authority that transcended priests and bishops. Despite threats of excommunication by the Church, large crowds gathered for the apparitions of Senta Roos. Furthermore, one group of residents wrote to Church authorities suggesting that the ‘greatest sinners’ sat in the bishop’s office of Speyer. They felt that Catholic leaders abandoned their followers in a time of need, much as they did in ‘Hitler’s time’ when they avoided public protest and left their ‘flock’ to their own devices.27 This sensitivity about the Church Struggles during the Third Reich undoubtedly received attention because of an especially harsh standoff between local Nazi officials and the Catholic population in the Palatinate.28 Like Müller, believers in the Fehrbach apparitions utilized the Church’s selective memory about persecu-tion under Nazism against German bishops by casting them as Nazi collabo-rators and Catholic congregants as victims.

Senta Roos next to a former POW who announces her revelations to devotees in Fehrbach.

(Bistumsarchiv Speyer, BO NA 23/10, 1/49, Fehrbach)

6![]()

This confrontation with the Church, however, was not without its ambiguities. In the first place, it replicated the patriarchal nature of the institution it attacked. In his renowned study of the nineteenth-century Marpingen apparitions, David Blackbourn argues that female visionaries ‘inverted’ the usual power relationship with male patriarchy,29 but postwar men quickly restrained the seers’ agency as spiritual advisors and publicists. Although women be-tween the ages of forty and sixty constituted the majority of Fehrbach supporters, they accepted leadership from a small number of men in the movement. The firm support of their local priest remained a crucial litmus test for the popularity of a pilgrimage site. Furthermore, a male schoolteacher, war veteran, and former POW announced the revelations of Senta Roos over a microphone rather than accept a young girl in an unrestrained leadership role. Although apparition movements challenged hierarchy, their assault left patriarchy untouched. Furthermore, the ultimate goal of apparition supporters was official recognition of the Fehrbach Madonna by the Church. When the Church recognised modern apparitions, such as in Fatima and Banneux, they usually reacted suspiciously at first but altered their course several years later. Pilgrims to Heroldsbach and Fehrbach expected such a fate for their apparitions. Over 2,000 people wrote to the Bishop of Speyer in hope of such a result. Despite their confrontation with institutional authority, it was the blessing of Church officials that these Marian pilgrims deeply craved.30

Fehrbach emphasized fears about consumerism, sexuality, and secularisation more than war memory. The defenders of the apparitions stressed the originality of their Madonna’s central message: ‘I am the mother of the conversion of sinners.’ The primary revelations delivered by the ‘simple and artless’ seer encouraged the return of prodigal Catholics back to the Church. Senta Roos’ poverty and seeming rejection of material goods received much more public exposure than the fact that she had lost her parents to bombs during World War II.31 In this context, Fehrbach pilgrims regularly contrasted their austerity and faith with the growth of the market economy and its perceived connection with the sex industry in the Federal Republic. One woman wrote to the bish-op’s office: ‘When, for example, a bar opens with a regular strip tease in an all-Catholic town such as Fehrbach […], then the call to emergency by the Virgin Mother cannot be loud enough.’32 Pilgrims associated their anxiety about consumerism and commercial sexuality with their fear of secularisation. One Fehrbacher wrote: ‘If our priests hold devotions to Mary, who is there? Two or three old hags. The masses would rather seek pleasure. But a poor orphan was sought by the mother of God to convert these sinners.’ Therefore, apparition worshipers celebrated ‘countless’ stories of wayward Christians who found religion once again after sexual misconduct and lapsed religious practice thanks to contact with the Fehrbach Madonna.33

The specter of a new popular culture and its secular influence stoked the fears of Fehrbach supporters as much as the prospect of another Russian invasion frightened Heroldsbach activists. This difference resulted from Fehrbach’s proximity to towns modernised by American military bases during the 1950s. Previously agricultural Palatinate towns, such as Baumholder, experienced radical economic and social changes with construction projects by the American military, starting in 1950. Christian politicians, priests, and social workers articulated deep anxiety about the moral climate of the region during this transformation.34 While the Cold War provided the context for Heroldsbach because of its location near Eastern Europe, the pilgrims to Fehrbach expressed a greater concern with the threat posed by Americanisation and consumerism to ethical values, religious traditions, and rural ways of life in the Palatinate.

7![]()

2. The Decline of the Marian Movement

Existing scholarship about faith in heavenly intercession naturally accentuates the most popular movements, but analysis of those that attracted less attention reveals just as much about this era of Marian piety. For example, a series of less accepted apparitions also transpired in the town of Niederhabbach when a thirty-five year old rural labourer who was a war veteran, a former POW, and a refugee from the east, saw the Virgin Mary multiple times in the summer of 1952 following a visit to Heroldsbach. After he predicted a vision for early September, between 5,000-8,000 people travelled to his small town where pilgrims insisted that they saw the sun rotate and change colour before the seer’s latest vision. The crowd included mostly middle aged and older women, a few ‘unhappy looking men’, Heroldsbach supporters, a row of sick people hoping for cures, and Hungarian ‘gypsies’. Reporting on conversations in the crowd, a journalist stated: ‘The names of miracles came up: Fatima, Lourdes, Konnersreuth, Heroldsbach […] above all Heroldsbach.’ Fritz Müller arrived with cards proclaiming the authenticity of the Niederhabbach apparitions, and another Heroldsbach supporter presented the seer’s stepson with an oil painting of the Heroldsbach Madonna.

The behavior of spectators, however, demonstrated deepening scepticism regarding controversial apparitions. Most press reports described an ambivalent crowd. Despite ‘ecstatic’ pilgrims who exhibited intense devotion, many curiosity seekers ‘came who did not share the beliefs of those standing next to them. They stared at the people, baffled at the mass psychosis.’ One journalist observed two friends arguing because one man did not believe in the ‘sun miracle’ the other claimed to witness. As more apparitions occurred, they received greater publicity in the growing tabloid press and caused increasing disillusionment among the mainstream Catholic population.35

The Niederhabbach visions failed to capture the popular imagination because they lacked many of the essential features present in Heroldsbach and Fehrbach. First, the seer possessed the support of neither a local priest nor even a spiritual advisor to provide more legitimacy to his visions. As an adult male rather than a young girl, he departed from the usual script for ‘successful’ apparitions. Furthermore, this visionary lacked either the infrastructure or even the interest in creating a popular movement. According to the report of a Catholic theologian investigating the events of September 1952, he experienced relief when the crowd dispersed from the front of his house and reacted with indifference to the alleged solar miracle. His experience as a soldier, POW, and eastern refugee, in combination with narratives of German suffering during the 1950s created the potential for a strong following.36 However, his lack of education, profane language, erratic behaviour, and unconvincing descriptions of visions failed to impress potential followers as well as Church officials. The Church banned worship at Niederhabbach, and no movement comparable to Heede, Heroldsbach, or Fehrbach emerged.

8![]()

Despite the quick demise of the Niederhabbach movement, it nonetheless indicated the persistence of the confrontation between apparition supporters and the clergy. Although the Niederhabbach seer neglected the usual themes of anti-Communism, anti-Nazism, and anti-consumerism, he nonetheless used his visions to critique the rigidity of clerical oversight. When interviewed by Church officials about his apparitions, he said, ‘During the first visit, she [i.e. the Virgin Mary] said that many priests would berate me over the miracles. Today she said that many priests have indeed berated the apparitions.’37 That such a crowd gathered to see a mentally unstable visionary who was indifferent to his own popularity is in itself a powerful testament to the geographical reach and determination of Heroldsbach’s supporters and the willingness of thousands of Catholic to defy Church leaders on the issue of religious miracles.

Another series of Marian miracles occurred in the Palatinate town of Rodalben, but they sparked more protests against suspicious claims of supernatural visions than they did faith in the Virgin Mary. A twenty-six year old woman claimed that Mary healed her from debilitating cramps and appeared with other heavenly figures in multiple apparitions. Anneliese Wafzig’s hallucinations attracted the devotion of about sixty regular pilgrims who formed a so-called ‘prayer community’ as well as hundreds of visitors. The Rodalben visions contained the same apocalyptic tone as Heroldsbach and Fehrbach. Mary and other saints warned Anneliese about calamities if she failed in her role as conduit to win back lapsed Christians. However, the visions rarely mentioned Communism, Russians, or a potential third world war. Rather they encouraged conversion of sinners, such as a man in the same hospital where Anneliese experienced her cure. The Blessed Mother instructed her to place a Catholic medallion under his pillow so he would repent his sins. Finally, the Wafzig family and their followers undermined Church authority and articulated a reformed version of Catholic piety through the visions. For example, one of Anneliese Wafzig’s spiritual advisors wrote, ‘Not a religion of violence and strict laws, but a religion of love and the heart can and will save people.’ These pious dissidents believed that a more flexible and less legalistic approach to doctrine would not only lend their beliefs legitimacy but convert others to Catholicism.

The significant presence of lay associations in the industrial town of Rodalben – far stronger than in the agricultural towns of Heede, Heroldsbach, and Fehrbach – ensured that its 5,000 Catholics supported their priest and the Church hierarchy in opposition to these alleged miracles. While Church leaders excommunicated the seer, her family, and several followers, Catholic youth groups and the Kolping Association spearheaded spontaneous protests against the apparitions in the hope of preventing an embarrassing spectacle. In the early days of the Rodalben events, the parish priest complained that Wafzig’s visions became the butt of jokes at the local factory. Relations with the town worsened when Wafzig supporters accused the Catholic youth of violently attacking her. Although the local police discredited this attack as fantasy, the Rodalben Catholic youth had in fact vandalised devotional material of the nearby Fehrbach apparitions as well.38

Angry Catholics gather to oppose the Rodalben Prayer Circle on July 1, 1952.

(Bistumsarchiv Speyer, BO NA 23/10, 2/51, Bonaventur Meyer, Bericht über Rodalben)

9![]()

The tension culminated on July 1, 1952 when the Rodalben ‘prayer community’ ventured to the cemetery in order to witness a predicted miracle by the Virgin Mary. Over 1,000 spectators cursed, threw stones, and intimidated them with threats of further violence. The men leading this crowd yelled, ‘You may not pass. We are the Kolping Association. You are blasphemers, dogs, and false priests.’ The Marian devotees retreated indoors under the reluctant protection of the police. Once inside the residence, the tumult spilled onto their front lawn as hecklers threw stones at the windows, threatened to storm the house, and even discharged a revolver. One pilgrim ‘had the feeling that if this mob succeeded in entering the house, they would tear us all to pieces’. At the moment when violence outside reached a climax, the pilgrims claimed a miracle occurred indoors. The visionary and her supporters professed that a vision of Jesus miraculously engraved one of her garments in blood with an image of a communion host and chalice.

Members of the Rodalben Prayer Circle worship the ‘Blood Miracle’ of 1952.

(Bistumsarchiv Speyer, BO NA 23/10, 2/51, Bonaventur Meyer, Bericht über Rodalben)

The altar honouring the Rodalben ‘Blood Miracle’, 1952.

(Bistumsarchiv Speyer, BO NA 23/10, 2/51, Bonaventur Meyer, Bericht über Rodalben)

Although it receives less scholarly attention than the other apparitions, the Rodalben phenomenon remains significant for several reasons. Much like the more popular spectacles in Fehrbach, these miracles emphasised fears of secularisation rather than anti-Communism. Rodalben shared Fehrbach’s close proximity to the new American military bases in the Palatinate. When Anneliese saw a vision of Jesus Christ in tears during the ‘blood miracle’, it suggested anger with secularisation and scepticism by other Catholics rather than the imminent threat of war.39 Second, those excommunicated for worshipping apparitions explicitly linked their fate to religious victims of Nazi persecution during the tense Church-State struggle in the Palatinate of the 1930s. The family of the Rodalben visionary claimed they had resisted National Socialism. One of their supporters argued that they had been the ‘only’ family in town that remained loyal to Catholicism, and that they had opened their home to those forced into hiding by the regime. The family also insisted that the local pastor had entrusted them with incriminating documents that he wanted to hide from the Gestapo. Once again, those devoted to Marian apparitions drew parallels between the Nazi suppression of free speech and institutional efforts to discourage miracles not sponsored by the Vatican.

One of two monks who became spiritual advisors to Anneliese Wafzig used traumatic World War II experiences to defend the Rodalben apparitions. Father Gebhard Heyder had spent time in a concentration camp for an inflammatory sermon and compared this experience to the Church’s attempts to silence Rodalben supporters. His superior within the Carmelite order offered the following description: ‘It is as a consequence of his time in the KZ and his suffering within the KZ that he developed an exaggerated sense of justice and punctilious drive to fight all injustice in the world.’ A disproportionate number of the small circle of men attracted to Catholic mysticism had endured concentration camps, POW camps, or expulsion from the east. Although his younger colleague and protégé, Father Wolfgang Kimmel, had fought as an officer in World War II, Heyder’s victimisation received more attention in com-plaints about the Church because it suggested a comparison between Nazi political oppression and ecclesiastical repression of apparition devotion.40 This encouragement of religiosity previously deemed feminine by men hardened through imprisonment and war also continued the alternate direction in postwar Catholic masculinity started by Heroldsbach supporters, such as Fritz Müller.41

10![]()

Furthermore, the events in Rodalben highlight the divisions created by the apparition movement during the early 1950s. Bishops and priests became the fiercest enemies of Heroldsbach and Fehrbach. However, Catholic youth groups and confessional associations led attacks in Rodalben, indicating fatigue among lay leaders with what they viewed as superstitious, dated, and embarrassing forms of piety by rural women.42 The wave of apparitions created a gulf between the traditional power brokers of the Catholic milieu, including the clergy and confessional associations, and rural adherents to piety outside the control of the institutional Church. Rodalben illustrates how strong confessional associations that were less prominent in most rural areas made the rise of grass-roots movements based on unsanctioned forms of piety more difficult.

The gendered relationships within the Rodalben prayer circle followed a similar pattern to Marian communities in Heede, Heroldsbach, and Fehrbach. Although Anneliese exercised spiritual power as a seer, she required male lead-ership for more widespread legitimacy. She began with a lay advisor named Fideli Ransberger, an estranged Heroldsbach activist and former war veteran. After the Church excommunicated the Wafzig family and accusations surfaced about an affair between Wafzig and Ransberger, he fled. As mentioned above, Wolfgang Kimmel and Gebhard Heyder succeeded Ransberger as leaders of the small but intensely pious group. Anneliese Wafzig ended her brief period as a local celebrity by retreating to the care of Heroldsbach’s most prominent ad-herent, Dr. Johannes B. Walz.43 Miraculous visions undoubtedly provided Wafzig a ‘respite from powerlessness’,44 but constant male supervision limited their potential for emancipation.

The Rodalben movement remained unpopular for many reasons. The crucial support of the local clergy eluded the Wafzig family, and clerical hostility, apparently, inspired the opposition of others in the town. Diocesan leaders observed: ‘To the honour of the congregation in Rodalben one must conclude that local Catholics with very few exceptions have followed their leaders and local clergy with strict discipline.’ Adherents of the more popular apparition movement in the neighbouring town of Fehrbach also looked with more scorn than enthusiasm on the events in Rodalben. Fehrbach pilgrims resented the Rodalben circle as a rival and worried that the Wafzig family’s unpopularity would detract from their own claims of authenticity.45 Although influenced by Heroldsbach through Ransberger and Heyder, Rodalben pilgrims proved incapable of winning support from the local and national network of Catholics fascinated with acts of intervention by heavenly figures.

11![]()

The momentum of the apparition movement declined in part because of threats of excommunication and in part because of fatigue with numerous reports of miracles; and the institutional Church reaffirmed its power and influence by harnessing Marian piety within the boundaries of Church doctrine and practice. Pope Pius XII declared 1954 a Marian Year, and Cardinal Frings organized the Peregrinatio Mariae (Traveling Madonna) in the archdiocese of Cologne.46 This event brought an officially recognised model of the Fatima statue to 300 Churches throughout the Rhineland. The Church ultimately reduced the influence of West Germany’s seers and stigmatics by reappropriating their messages within the context of Church sponsored doctrines. The statue attracted 60,000 visitors a day for over a week in Cologne and remained popular in its sojourn through the archdiocese.47 Even sceptical clergy embraced the successful tour by the Fatima replica perhaps because no new miracles or cures surfaced.48 The tour of the ‘Traveling Madonna’ proved the popularity of Marian worship in the Rhineland, but also illustrated the wider acceptance of authorised forms of piety in industrialised regions with carefully organised religious associations.

Male lay leaders carry the Fatima Statue during the Peregrinatio Mariae in 1954.

(Historisches Archiv des Erzbistums Köln, Seelsorgeamt Heinen 118: Peregrinatio Mariae; Photo: Theo Felton, Cologne)

Although the Church rejected the German apparition movement of the early 1950s, the Fatima celebration reflected its Cold War themes with warnings about a third world war.49 In the midst of sincere and heartfelt expressions of Marian piety by hundreds of thousands of Catholics, clergymen also fretted about secular impulses in the capitalist West. Cardinal Frings complained, ‘The amazing economic rise of the Federal Republic has not seen a parallel renewal in religious and moral values.’50 Finally, this event relegated women to even more secondary roles than the prayer circles in Heede, Fehrbach, and Rodalben. Imposing order on the subverted gender order, male associations and youth groups carried the Madonna during processions and male Jesuits rather than female seers distributed the message of Fatima. Women formed the majority of spectators, but remained on the margins of all rituals during the statue’s visits. In sum, the hierarchy defused the confrontation with Marian supporters by reappropriating Marian messages about fearing Communism, consumerism, and secularisation and seizing control of the ‘goods of salvation’ from the excommunicated rebels in Bavaria, the Rhineland, and the Palatinate.

Women as spectators during the Peregrinatio Mariae in 1954.

(Historisches Archiv des Erzbistums Köln, Seelsorgeamt Heinen 118: Peregrinatio Mariae; Photo: Theo Felton, Cologne)

12![]()

3. Therese Neumann: From Obscurity to Beatification

A stigmatic named Therese Neumann of Konnersreuth became Germany’s most popular prophet during the late 1920s and remained the most influential figure in the subculture of German Catholic miracles after World War II. Al-though her messages and tone sometimes differed from the seers of West Germany’s apparition sites, Neumann and her followers engaged many of the same issues by challenging the authority of the Church, posing as opponents of Nazism, and offering an alternative to the encroaching consumerist society of the 1950s.

The charismatic visionary affectionately known as Resl became prominent upon hearing heavenly voices and regaining the ability to see and walk during the mid-1920s. She experienced stigmata on her hands and feet, allegedly ate only communion hosts for decades, and cried tears of blood. Press reports about her visions, the support of her local priest, Father Josef Naber, and accounts of her ascetic lifestyle made Neumann a worldwide celebrity. Followers flocked to her home for a glimpse of her bloody trances and an inner core formed what became the ‘Konnersreuth Circle’. Although many observers associate her popularity with the interwar period, Resl emerged after World War II as an object of devotion as well as a target for scepticism in debates about the supernatural intercession of heavenly figures.51

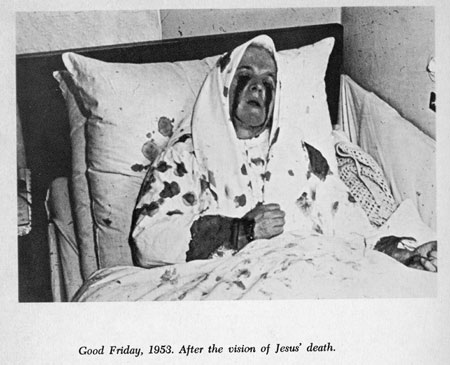

Therese Neumann on Good Friday, 1953.

(Johannes Steiner, Therese Neumann. A Portrait Based on Authentic Accounts, Journals, and Documents, Staten Island 1967)

The postwar popularity of the isolated town of Konnersreuth illustrated the vast audience sympathetic toward religious miracles within the Catholic community. Neumann and her circle retained the firm support of the local population. One Konnersreuth observer noted: ‘In 1948 I personally inquired among the neighbours about Neumann’s strict fasting and concluded that the population is completely convinced. I sometimes had the impression that it was considered an insult to even pose the question.’ Her popularity revived after the fall of Nazism as pious Catholics and curiosity seekers from Germany, Europe, and American army bases sought an audience with her and an opportunity to view her almost weekly stigmata. When her health permitted, crowds of be-tween 10,000 and 20,000 people travelled to Konnersreuth on Good Friday throughout the 1950s. Although Neumann reportedly rejected the Heroldsbach visions as inauthentic, connections existed between her followers and those of the eleven apparitions in the Federal Republic. For example, Fritz Müller published a pamphlet contradicting books that accused her of fraudulence.52 Unlike the seers of Heroldsbach and Fehrbach, Neumann’s popularity persevered. Her funeral in 1962 attracted 10,000 mourners, and several chapters of the Konnersreuth Circle opened throughout West Germany and the United States to lobby Regensburg Church officials for her beatification process, which started in 2005 after the diocese received over 40,000 letters.53

13![]()

Therese Neumann’s challenge to Church authority endured because she confronted the hierarchy with less rancour than the faithful of Marian apparitions. Although the Konnersreuth Circle suffered bitter attacks by Catholics sceptical about Therese’s miracles and embarrassed by the bloody images of her that appeared in the press, they rarely responded with the heated rhetoric of a man like Fritz Müller. The primary confrontation emerged over medical examinations of Therese to prove the authenticity of her miracles. Under pressure from the diocese of Regensburg, Therese submitted to an examination of her weight gain while fasting during the late 1920s. After a medical journal published inconclusive results without consent of the family, the Church demanded a second clinical examination. Despite persistent pressure from German clergy, the Neumann family refused further tests because they feared Therese would become the focus of endless medical fascination and a target of Nazi programmes against ‘asocials’. After the war, the Neumanns demonstrated a renewed willingness for a medical examination, but Church leadership sought neutral distance from the popular but controversial Konnersreuth phenomenon. Throughout the ordeal, the family noted the advice of Father Naber: in the long ‘history of mysticism, that many people favoured with this special grace have been harshly handled by the Church, and later beatified’. While willing to challenge the authority of the Church when it questioned the legitimacy of Neumann’s contact with God, Therese’s family remained conciliatory enough for the possibility of future reconciliation, which finally came after Resl’s death in 1962.

The Konnersreuth Circle never directly criticised the behaviour of Church leadership under the Third Reich but subtly accented its anti-Nazi credentials after the war. Her followers highlighted Neumann’s vulnerability to National Socialist programmes against the disabled as well as her links to two prominent Catholic resisters against the Third Reich: journalist Fritz Gerlich and Father Ingbert Naab. Gerlich, initially a sceptic of Neumann when covering her story for the Münchener Neueste Nachrichten, credited Resl with his conversion to Catholicism. Neumann’s supporters claimed she encouraged his dissent against Nazism until his capture and execution. Allegedly, Neumann’s prophesies about Gestapo raids saved Naab’s life until he died of natural causes in exile. Publications by her supporters also discussed the mockery of Neumann in Das Schwarze Korps and the police interrogation of her family members. Although Neumann’s retreat from publicity during the Third Reich hardly constituted resistance, the tension between Konnersreuth and the NSDAP sparked numerous rumours. One of the many American soldiers who visited her during the postwar occupation claimed: ‘I remember that Hitler wanted Therese killed and even sent soldiers to her home to kill her. She met them at the door with her bleeding wounds and they were frightened away.’ Although the Konnersreuth Circle did not explicitly equate its problems with the Church and the Nazis, it frequently alluded to the simultaneous pressure they endured from Church authorities seeking a medical examination and NSDAP scrutiny during the 1930s.54

Konnersreuth activists also illustrated the tendency by many Catholic mystics to address fears of consumerism rather than apocalypse and nuclear war despite the town’s location near the border with Czechoslovakia. Neumann rarely mentioned anti-Communism, Russians, or other Cold War themes. Rather, her circle depicted Neumann as a counterpoint to the increasing ur-banisation and material success of the early Federal Republic. Pilgrims emphasised the isolated simplicity of both Konnersreuth and its seer. One observer commented: ‘Konnersreuth is in every respect the small, poor, and remote mountain town that it was twenty-five years ago.’ The town consciously rejected the souvenir shops and tourist business prevalent at most pilgrimage sites. Other contemporaries commented on the innocence, naivety, and child-like disposition of Neumann. These images of rural simplicity posed a stark contrast with the changes stimulated by the economic miracle, construction of American bases, and emerging popular culture in large West German cities as well as much of the countryside. German writer Luise Rinser wrote: ‘A person such as Therese Neumann is proof that in the middle of our bustling world whose silly conventions overestimate the world of work, success, money, bourgeois respectability, and similar fleeting things, another world exists that offers a spiritual life rather than a life of materialism.’55 Neumann represented German Catholic angst at the changing values during West Germany’s stunning recovery from the war.

14![]()

Finally, like many apparition movements, the circle around Therese Neumann respected the gender hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church. Neumann’s potential for subversion seemed less threatening because she relied on her priest, her father, and her brother for most major decisions. Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, she welcomed a second clinical exam, but deferred to her father when he refused. Father Naber and Ferdinand Neumann also controlled access to Resl and handled relations with the public. While Therese Neumann excelled in a role traditionally gendered female by Catholic tradition, she voluntarily limited her agency to the realm of apolitical and feminine mysticism. In sum, the Konnersreuth Circle struck a balance between deference and challenge to Church authority that ultimately provided them access to the ‘goods of salvation’ with the start of the beatification process in 2005. Like other devotees of Catholic visionaries, they resisted the authority of Church leaders but ultimately tempered their resistance in the hope of gaining official recognition.

This analysis of Catholic mysticism in the early years of the Federal Republic illustrates the existence of a short-lived revival of Marian worship and stigmata caused by spontaneous action from below as well as calculated planning by the hierarchy. This movement extended from Bavaria to the Rhineland and beyond. With apparitions in multiple locations and followers from several regions and countries, postwar faith in Marian intercession transcended any one locality.

This essay confirms the conclusions of the historiography that during the aftermath of war and the onset of the Cold War, Catholics coped with their anxieties through devotion to the Virgin Mary. The disproportionate number of war veterans and concentration camp survivors among the minority of males in these movements offer further support for this thesis. However, it also asserts that religious miracles engaged the other important tropes within the Catholic community of the early Federal Republic: anxiety about new forms of popular culture and early debates about the Nazi past. In postwar West Germany, Catholic politicians, clergy, and lay leaders supported the democratic process and western allies that empowered Christian Democracy but also waged a moral campaign against the materialism and popular culture that came with this western integration.56 The pious Catholics of Fehrbach, Rodalben, and Konnersreuth joined the bishops, CDU leaders, and Christian social workers in the initial articulation of this postwar anti-consumerist trope that would last into the 1960s. Furthermore, apparition supporters reshaped the Catholic narrative of victimhood by the Third Reich as a weapon against the institutional authorities who excommunicated them. They altered the selective memory of Catholic persecution to suggest that while Church authorities collaborated, ordinary congregants suffered alone from the anti-Catholic bias of the National Socialist regime. Despite utilising anti-Nazi rhetoric to defend their Marian worship, they ignored Nazi antisemitism and the collaboration of some of their leaders. In sum, the Marian movement mobilised hundreds of thousands of Catholics who operated on the fringes of the German Catholic milieu by engaging mainstream tropes about anti-Communism, anti-consumerism, and anti-Nazism.

15![]()

This movement, however, sparked division within the Catholic community as well. Rural women, former POWs, camp survivors, and provincial priests instigated a standoff with other priests, bishops, and lay associations who found the miracles embarrassing and perilous to their spiritual authority. While pilgrims circumvented clerical authority by seeking salvation through direct access to God rather than the Church, bishops threatened some of their most devout followers with excommunication and male association members even violently attacked other Catholics in Rodalben. This rebellion ultimately failed, as was the case according to Bourdieu, with most power struggles from within the ‘religious field’. Although the political power of the CDU played no concrete role in attempts at Church discipline, religious leaders relied on tools provided by their elite status to combat Marian pilgrims: theological education and control over canon law. Roman Catholic leaders operated from a position of power because they possessed what their adversaries ultimately desired: official standing within the Church and recognition by the hierarchy. German bishops successfully isolated their most outspoken opponents through excommunication, verbal abuse, and even violence. They also re-established control over the most popular elements of Marian worship with the Peregrinatio Mariae and ultimately appropriated Therese Neumann.

The most compelling element of this surge in Catholic mysticism remains its quick rise and fall between 1940 and 1955. On the one hand, the apparition boom illustrates the ‘braided’ narrative of secularisation observed by Robert Orsi in the United States. Orsi rejects a narrative that limits the path of modern religiosity to a ‘normative trajectory toward the modern’. Rather under the surface of trends that gradually diminished belief in the supernatural, ‘the children and grandchildren of the modernising generation rediscovered old devotional practices’.57 While other parts of the Catholic community became secular, sought modern reforms, or encouraged a return to the Catholic milieu of the 1920s, thousands of rural Catholics reformulated the values of the Lourdes and Fatima apparitions to articulate anxiety with the early Federal Republic and the Cold War in a divided Catholic community. For a decade, Marian pilgrims undertook dynamic forms of worship, while mainstream Catholics participated less frequently in Sunday services and confessional associational life. However, the popularity of faith in miracles declined rapidly after 1954. Enthusiasm for the Church-sponsored Fatima statue waned, and the seers of the 1950s disappeared except for Therese Neumann. Bourdieu argues that the preservation of power in the religious field depends on one’s ability to meet the needs of religious consumers most efficiently.58 Perhaps the Church discipline of the early 1950s alienated some of their most enthusiastic consumers, causing disunity at a fragile moment of reconstruction and secularisation. Furthermore, the German Catholic Church seemed more effective at winning power struggles with their most pious followers than competing with the emerging affluence and access to popular culture during the 1950s. As enthusiasm for miraculous visions faded with the growing economic and political stability of the Federal Republic, Church pews and membership in religious associations also continued their descent into the 1960s.

1 Ruth Harris, Lourdes. Body and Spirit in the Secular Age, New York 1999; Sandra Simdars-Swartz, Encountering Mary. Visions of Mary from La Salette to Medjugorje, Princeton 1991; Thomas A. Kselman, Miracles and Prophesies in Nineteenth-Century France, New Brunswick 1983; Paula M. Kane, Marian Devotion since 1940: Continuity or Casualty?, in: James M. O’Toole (ed.), Habits of Devotion. Catholic Religious Practice in Twentieth-Century America, Ithaca 2004, pp. 89-129.

2 Monique Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen. Marienerscheinungskulte im 20. Jahrhundert, Tübingen 2006, pp. 18-19, 169-170.

3 M. Rainer Lepsius, Parteiensystem und Sozialstruktur. Zum Problem der Demokratisierung der deutschen Gesellschaft, in: Wilhelm Abel (ed.), Wirtschaft, Geschichte und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Stuttgart 1966, pp. 371-393. For reviews of the historiography, see Arbeitskreis für kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (AKKZG), Münster, Katholiken zwischen Tradition und Moderne. Das katholische Milieu als Forschungsaufgabe, in: Westfälische Forschungen 43 (1993), pp. 592-593; Oded Heilbronner, From Ghetto to Ghetto: The Place of German Catholic Society in Recent Historiography, in: Journal of Modern History 72 (2000), pp. 60-85; Michael E. O’Sullivan, From Catholic Milieu to Lived Religion: The Social and Cultural History of Modern German Catholicism, in: History Compass 7 (2009), pp. 837-861; Mark Edward Ruff, Integrating Religion into the Historical Mainstream: Recent Literature on Religion in the Federal Republic of Germany, in: Central European History 42 (2009), pp. 307-337.

4 Anna Maria Zumholz, Volksfrömmigkeit und katholisches Milieu. Marienerscheinungen in Heede 1937–1940 im Spannungsfeld von Volksfrömmigkeit, nationalsozialistischem Regime und kirchlicher Hierarchie, Cloppenburg 2004.

5 Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2); Cornelia Göksu, Heroldsbach. Eine verbotene Wallfahrt, Würzburg 1991.

6 Michael Phayer, Pius XII, the Holocaust, and the Cold War, Bloomington 2008.

7 Wilhelm Damberg, Abschied vom Milieu? Katholizismus im Bistum Münster und in den Niederlanden, 1945–1980, Paderborn 1997; Mark Edward Ruff, The Wayward Flock. Catholic Youth in Postwar West Germany, 1945–1965, Chapel Hill 2005.

8 Werner Blessing, Deutschland in Not, wir im Glauben…’ Kirche und Kirchenvolk in einer katholischen Region 1933–1949, in: Martin Broszat/Klaus-Dietmar Henke/Hans Woller (eds), Von Stalingrad zur Währungsreform. Zur Sozialgeschichte des Umbruchs in Deutschland, Munich 1988, pp. 3-111, here p. 17.

9 Terry Rey, Marketing the Goods of Salvation: Bourdieu on Religion, in: Religion 34 (2004), pp. 331-343; Bradford Verter, Spiritual Capital: Theorizing Religion with Bourdieu against Bourdieu, in: Sociological Theory 21 (2003) No. 2, pp. 150-174; William F. Hanks, Pierre Bourdieu and the Practices of Language, in: Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (2005), pp. 67-83.

10 The author would like to thank Monique Scheer and two anonymous reviewers for their feedback on earlier drafts of this essay as well as the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and Marist College for the funding that made the archival research possible.

11 Zumholz, Volksfrömmigkeit (fn. 4), pp. 327, 342, 451, 488, 661-665.

12 Historisches Archiv des Erzbistums Köln (AEK), Gen. II 31.6, 4: Wunderbare Erscheinungen, 1.1.1952 – 21.12.1959, II. Teil; Göksu, Heroldsbach (fn. 5), pp. 13-23, 24-29, 36-37, 62-65, 75-78, 81-87.

13 Tumult am Wallfahrtsort, in: Neue Illustrierte, 25.10.1950, p. 8.

14 Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), pp. 227-245.

15 Thomas Breuer, Verordneter Wandel? Der Widerstreit zwischen nationalsozialistischem Herrschaftsanspruch und traditionaler Lebenswelt im Erzbistum Bamberg, Mainz 1992, p. 195; Tobias Dietrich, Konfession im Dorf. Westeuropäische Erfahrungen im 19. Jahrhundert, Cologne 2004; Ruff, The Wayward Flock (fn. 7), pp. 144-151.

16 Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), pp. 207-245.

17 AEK, Gen. II 31.6a, 1: Wunderbare Erscheinungen (Heroldsbach), Fritz Müller, Generalangriff für Heroldsbach: Entweder reden oder verdammt werden, 1952. The details of Müller’s biography were confirmed in the following source: Das Lied des Obergefreiten: Marien-Erscheinungen, in: Spiegel, 17.9.1952, pp. 8-9.

18 Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), pp. 208-209.

19 AEK, Gen. II 31.6a, 1: Fritz Müller, Offener Brief an Seine Heiligkeit Papst Pius XII., 1952, and Hoffentlich hält der Westfale stand!

20 AEK, Gen. II 31.6a, 2: Heroldsbach, Teil II, Fritz Müller, Maria weint…!/Katholischer Existen-zialismus?, 15.1.1954 (my translation).

21 Doris Kaufmann, Katholisches Milieu in Münster 1928–1933. Politische Aktionsformen und geschlechtsspezifische Verhaltensräume, Düsseldorf 1984, pp. 97-113; Irmtraud Götz von Olenhusen, Jugendreich, Gottesreich, Deutsches Reich. Junge Generation, Religion und Politik, 1928–1933, Cologne 1987.

22 Uta Poiger, Jazz, Rock, and Rebels. Cold War Politics and American Culture in a Divided Germany, Berkeley 2000, pp. 72-79; Ruff, The Wayward Flock (fn. 7), pp. 58-77.

23 Bistumsarchiv Speyer (BaS), BO NA 23/10, 1/49: Fehrbach, Dr. Scholler an Pilger-Druckerei Speyer, 29.5.1952; Göksu, Heroldsbach (fn. 5), pp. 114-115.

24 AEK, Gen. II 31.6, 1: Wunderbare Erscheinungen, 1945–1951, Ein Fehrbacher an Seine Exzellenz den Hochwürdigsten Herrn Bischof von Speyer Dr. Josef Wendel, 16.9.1950.

25 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: Schriftleitung Der christliche Pilger. Bistumsblatt für die Diözese Speyer, 10.8.1950; Abschrift, Dr. Fritz Nees, Rechtsanwalt, Mainz 1951.

26 Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), pp. 200-201.

27 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: ‘Anhänger von Fehrbach’, Heinrich Kuntz (Fehrbach) an Bischöfl. Ordinariat Speyer, 23.7.1950; ‘Andere Diözese und Fehrbach’, Kath. Pfarramt Murg (Baden) an Bischöfl. Ordinariat Speyer, 23.11.1951; Rosa Haber, Anna Klein et al. an Bischöfl. Ordinariat, September 1950.

28 Maria Höhn, GIs and Fräuleins. The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany, Chapel Hill 2002, pp. 22-25, 116-117; Karl Heinz Debus, Die großen Kirchen unter dem Hakenkreuz. Kirchen und Religionsgemeinschaften in der Pfalz 1933–1945, in: Gerhard Nestler/Hannes Ziegler (eds), Die Pfalz unterm Hakenkreuz. Eine deutsche Provinz während der nationalsozialistischen Terrorherrschaft, Landau 1993, pp. 227-272.

29 David Blackbourn, Marpingen. Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Nineteenth-Century Germany, New York 1994, pp. 7-15, 30-31, 140-141, 261-263.

30 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: ‘Anhänger von Fehrbach’, Robert Vath an Bischöfl. Ordinariat, September 1950; Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), p. 202.

31 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: Geschwister Peter (Helene Peter and Frau Knappo) an Hochw. Herr Böhm, St. Ingbert/Saar, 16.2.1952; Abschrift, Dr. Fritz Nees, Rechtanwalt, Mainz 1951.

32 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: M. J.-H. an Hochw. Bischöfl. Ordinariat, Fehrbach, 15.10.1952.

33 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: Rosa Haber, Anna Klein et al. an Bischöfl. Ordinariat, September 1950; Kath. Pfarramt Eußerthal-Pfalz an Hochw. Bischof, betrf. Bekehrung H. Mangold in Fehrbach, 25.4.1951; An das katholische Pfarramt Fehrbach, 17.1.1952.

34 Höhn, GIs and Fräuleins (fn. 28), pp. 31-51, 109-125.

35 AEK, Gen. II 31.6, 4: Das Erzbischöfliche Generalvikariat, Generalvikar Teusch an Erzbistum Köln, 5.9.1952; Generalvikar Teusch an den Hochwürdigen Herren Dechanten der Dekanate Bensberg, Neunkirchen, Wipperfürth, Gummersbach und Remscheid mit der Bitte um baldige Weitergabe an alle Welt- und Ordensgeistliche Ihres Dekanates, 10.9.1952; Bericht über die Vorgänge in Nieder-Habbach am Montag, den 8. September 1952, Direktor Daniels, Bensberg, 9.9.1952; Tausende warteten auf eine ‘Erscheinung’: Habbach, der Ort, der plötzlich von Menschen überfüllt war, in: Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, 9.9.1952, p. 8; Tausende pilgerten nach Frielingsdorf, in: Rheinisch-Bergische Kreiszeitung, 9.9.1952.

36 Robert G. Moeller, War Stories. The Search for a Usable Past in the Federal Republic of Germany, Berkeley 2001.

37 AEK, Gen. II 31.6, 4: Bericht über die Vorgänge in Nieder-Habbach am Montag, den 8. September 1952, Bensberg, Direktor Daniels; Das Lied des Obergefreiten (fn. 17).

38 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 2/51: Rodalben, Pfarramt Rodalben, 17.1.1952, Bericht über A. Wafzig und S. Ransberger; Kathol. Pfarramt Rodalben an Herrn Bischof, 14.12.1951; S. Ransberger an Bischof Josef Wendel, Teilprotokoll über die Erscheinungen, 1.2.1952; Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), p. 392.

39 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 2/51: Polizeiverwaltung/Rodalben, 1.7.1952; Augenzeugenbericht über die Vorgänge in Rodalben, Rheinpfalz bei Pirmasens von Pater Augustinus a S. Maria (Wolfgang Kimmel) O.C.D.; Augenzeugen-Bericht über die Vorgänge in der Nacht vom 1. auf 2. Juli 1952 in Rodalben, Rheinpfalz von P. Gebhard Heyder O.C.D.

40 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 2/51: Rodalben, S. Ransberger an Bischof Josef Wendel, 1.2.1952; Bischöfl. Ordinariat an Provinzialamt der Unb. Karmeliten, Munich, 18.8.1952; Anton Fischer an Bischof Dr. Isidor Emmanuel, Speyer, 6.8.1954.

41 For Scheer’s description of Johannes Maria Höcht, another former concentration camp survivor turned apparition activist, see Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), pp. 372-384.

42 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 2/51: Kolpingfamilie, 21.1.1953.

43 BaS, BO NA 23/10, 2/51: Aktennotiz, 27.10.1952.

44 Blackbourn, Marpingen (fn. 29), pp. 30-31.

45 BaS BO NA 23/10 2/51, Erscheinungen um jedem Preis?, in: Der christliche Pilger. Bistumsblatt für die Diözese Speyer, 25.5.1952; BaS, BO NA 23/10, 1/49: ‘Anhänger von Fehrbach’, Dr. Fritz Nees (Rechtsanwalt Mainz) an den Herrn Schriftleiter des Bistumsblattes Der christliche Pilger, 31.5.1952.

46 Scheer, Rosenkranz und Kriegsvisionen (fn. 2), pp. 144-160.

47 AEK, Seelsorgeamt Heinen (SH) 104: Peregrinatio Mariae durch das Erzbistum Köln – Berichte und Korrespondenzen über Vorbereitung, Durchführung und Wirkungen, Bericht über den Verlauf der Peregrinatio Mariae in der Erzdiözese Köln im Marianischen Jahr 1954.

48 AEK, SH 104: Früchte des Marianischen Jahres und deren Erhaltung (no date, no author).

49 AEK, SH 102: Bezirksschulrat an Kardinal Frings, 4.9.1954.

50 AEK, SH 105: Botschaft von Fatima für Erzdiözese Köln: Kardinal Frings predigte am Vorabend des 1. Mai vor katholischen Arbeitern, in: Kölnische Rundschau, 1.5.1954.

51 Anna Maria Zumholz, Die Resistenz des katholischen Milieus: Seherinnen und Stigmatisierte in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, in: Irmtraud Götz von Olenhusen (ed.), Wunderbare Erscheinungen: Frauen und katholische Frömmigkeit im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Munich 1995, pp. 221-234; Luise Rinser, Die Wahrheit über Konnersreuth. Ein Bericht, Frankfurt a.M. 1953, pp. 140-150.

52 AEK, Gen. II 31.9, 1: Therese Neumann, Dr. jur. Herrn Mersmann an Erzbischof Buchberger in Regensberg, April 1953; 10,000 Menschen in Konnersreuth: Eigener Bericht, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 28.3.1959, and Fritz Müller, Sind Verleumdungen in der kath. Kirche gestattet? (no date); Tumult am Wallfahrtsort, in: Neue Illustrierte, 25.10.1950, p. 8; Thousands Visit Home of Therese Neumann and Witness Phenomenon on Good Friday, in: New York Times, 27.5.1948.

53 Rolf Thym, ‘Die Resl hat das nicht gewollt’: Eine Heilige?, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14.2.2005; Therese Neumann Dead at 64; said to Bear Wounds of Jesus, in: New York Times, 19.9.1962.

54 Johannes Steiner, Therese Neumann. A Portrait Based on Authentic Accounts, Journals, and Documents, Staten Island 1967, pp. 66-73; Rinser, Die Wahrheit (fn. 51), pp. 140-150; Noreen von Zwehl, America Salutes Therese Neumann. Testimonials of WWII Servicemen, Staten Island 1999; Helmut Witetschek, Pater Ingbert Naab, O.F.M. Cap. (1885–1935). Ein Prophet wider den Zeitgeist, Munich 1985, pp. 42-45; Zumholz, Die Resistenz (fn. 51), pp. 221-234.

55 AEK, Gen. II 31.9, 1: Dr. jur. Herrn Mersmann an Erzbischof Buchberger, 3.4.1952; Rinser, Die Wahrheit (fn. 51), pp. 173-174.

56 Robert G. Moeller, Protecting Motherhood. Women and the Family in the Politics of Postwar West Germany, Berkeley 1993; Elizabeth Heineman, What Difference Does a Husband Make? Women and Marital Status in Nazi and Post-War Germany, Berkeley 2003; Höhn, GIs and Fräuleins (fn. 28).

57 Robert A. Orsi, Between Heaven and Earth. The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars Who Study Them, Princeton 2005, pp. 9-10.

58 Rey, Marketing the Goods (fn. 9), pp. 337-338.

![]()